Petroleum trap

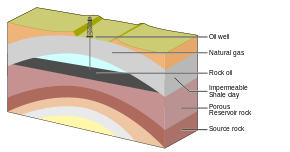

In petroleum geology, a trap is a geological structure affecting the reservoir rock and caprock of a petroleum system allowing the accumulation of hydrocarbons in a reservoir. Traps can be of two types: stratigraphic or structural. Structural traps are the most important type of trap as they represent the majority of the world's discovered petroleum resources.[1][2]

Structural traps

[edit]A structural trap is a type of geological trap that forms as a result of changes in the structure of the subsurface, due to tectonic, diapiric, gravitational, and compactional processes.[3][4]

Anticlinal trap

[edit]

An anticline is an area of the subsurface where the strata have been pushed into forming a domed shape. If there is a layer of impermeable rock present in this dome shape, then water-insoluble hydrocarbons can accumulate at the crest until the anticline is filled to the spill point (the highest point where hydrocarbons can escape the anticline).[5][6] This type of trap is by far the most significant to the hydrocarbon industry. Anticline traps are usually long oval domes of land that can often be seen by looking at a geological map or by flying over the land.

Fault trap

[edit]

A fault trap is formed by the movement of permeable and impermeable layers of rock along a fault plane. The permeable reservoir rock faults such that it is adjacent to an impermeable rock, preventing hydrocarbons from further migration.[7][6] In some cases, there can be an impermeable substance along the fault surface (such as clay) that also acts to prevent migration. This is known as clay smear.

Stratigraphic trap

[edit]In a stratigraphic trap, the geometry allowing the accumulation of hydrocarbons is of sedimentary origin and has not undergone any tectonic deformation. Such traps can be found in clinoforms, in a pinching-out sedimentary structure, under an unconformity or in a structure created by the creep of an evaporite.

Salt dome trap

[edit]

In a salt dome trap, masses of salt are pushed up through clastic rocks due to their greater buoyancy, eventually breaking through and rising towards the surface. This salt mass resembles an impermeable dome, and when it crosses a layer of permeable rock, in which hydrocarbons are migrating, it blocks the pathway in much the same manner as a fault trap.[8][6] This is one of the reasons why there is significant focus on subsurface salt imaging, despite the many technical challenges that accompany it.

Pinch-out trap

[edit]

Pinch-out traps are stratigraphic traps in which the petroleum reservoir thins around impermeable rock strata and eventually 'pinches out' with impermeable rock strata on either side, creating a trap.[6][9]

Hybrid trap

[edit]

Hybrid traps are the combination of two types of traps. In the case of tilted blocks, the initial reservoir geometry is the one of a fault-controlled structural trap, but the caprock is generally made by the draping sedimentation of mudstones during the oceanisation process.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Allen P.A. & Allen J.R. (1990) Basin Analysis. pp 373. Publ. Blackwell Publishing

- ^ "Petroleum Research Institution". Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ "structural trap". Energy Glossary. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ Gluyas, J. & Swarbrick, R. (2004) Petroleum Geoscience. Publ. Blackwell Publishing

- ^ Sheriff, R. E., Geldart, L. P. (1995). Exploration Seismology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 351. ISBN 0-521-46826-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Geology, Geography, and Meteorology". The Ultimate Visual Family Dictionary. New Delhi: D.K. Pub. 2012. p. 280-281. ISBN 978-0-1434-1954-9.

- ^ "Fault trap". Energy Glossary. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ "Petroleum Research Institute". Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ Nelson, Stephen A. (19 October 2015). "Energy Resources". Tulane University. Retrieved 1 January 2025.