Lincoln, Nebraska

Lincoln | |

|---|---|

Downtown Lincoln skyline | |

| Nickname: Star City[1] | |

Interactive map of Lincoln | |

| Coordinates: 40°48′33″N 96°40′41″W / 40.80917°N 96.67806°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Lancaster |

| Founded | 1856 (Lancaster) |

| Renamed | July 29, 1869 (Lincoln) |

| Incorporated | April 1, 1869 |

| Named for | Abraham Lincoln |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Leirion Gaylor Baird (D) |

| • City council | Members |

| • U.S. Congress | Mike Flood (R) |

| Area | |

| 100.45 sq mi (260.16 km2) | |

| • Land | 99.09 sq mi (256.63 km2) |

| • Water | 1.36 sq mi (3.52 km2) 1.4% |

| • Urban | 94.17 sq mi (243.9 km2) |

| • Metro | 1,422.269 sq mi (3,683.660 km2) |

| • CSA | 2,282.229 sq mi (5,910.95 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,201 ft (366 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| 291,082 | |

• Estimate (2023)[4] | 294,757 |

| • Density | 2,937.67/sq mi (1,134.24/km2) |

| • Urban | 291,217 (US: 139th) |

| • Urban density | 3,092.3/sq mi (1,193.9/km2) |

| • Metro | 342,117 (US: 152nd) |

| • Metro density | 240.5/sq mi (92.9/km2) |

| • CSA | 363,733 (US: 104th) |

| • CSA density | 159.4/sq mi (61.5/km2) |

| Demonym | Lincolnite |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | $25.459 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 68501-68510, 68512, 68514, 68516-68517, 68520-68524, 68526-68529, 68531, 68542, 68544, 68583, 68588 |

| Area codes | 402, 531 |

| FIPS code | 31-28000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 837279[3] |

| Website | lincoln.ne.gov |

| α. ^ 1 2 Area, city density, metro population/density and CSA population/density as of the 2021 estimate.[6][7] β. ^ Urban population/density as of the 2020 Census.[8] | |

Lincoln is the capital of the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Lancaster County. The city covers 100.4 square miles (260.035 km2) and had an estimated population of 294,757 in 2023. It is the state's second-most populous city and the 71st-largest in the United States. Lincoln is the economic and cultural anchor of the Lincoln Metropolitan and Lincoln-Beatrice Combined Statistical Areas, home to 361,921 people.

Lincoln was founded in 1856 as the village of Lancaster on the wild salt marshes and arroyos of what became Lancaster County. Renamed after President Abraham Lincoln, it became Nebraska's state capital in 1869. The Bertram G. Goodhue–designed state capitol building was completed in 1932, and is the nation's second-tallest capitol. As the city is the seat of government for the state of Nebraska, the state and the U.S. government are major employers. The University of Nebraska was founded in Lincoln in 1869. The university is Nebraska's largest, with 26,079 students enrolled, and the city's third-largest employer. Other primary employers fall into the service and manufacturing industries, including a growing high-tech sector. The region makes up a part of what is known as the Midwest Silicon Prairie.

Designated as a "refugee-friendly" city by the U.S. Department of State in the 1970s, the city was the 12th-largest resettlement site per capita in the country by 2000. Refugee Vietnamese, Karen (Burmese ethnic minority), Sudanese and Yazidi (Iraqi ethnic minority) people, as well as refugees from Iraq, the Middle East and Afghanistan, have resettled in the city. During the 2018–19 school year, Lincoln Public Schools provided support for about 3,000 students from 150 countries, who spoke 125 different languages.

History

[edit]Natives

[edit]Before the expansion westward of settlers, the prairie was covered with buffalo grass. Plains Indians, descendants of indigenous peoples who occupied the area for thousands of years, lived in and hunted along Salt Creek. The Pawnee, which included four tribes, lived in villages along the Platte River. The Great Sioux Nation, including the Ihanktowan-Ihanktowana and the Lakota, to the north and west, used Nebraska as a hunting and skirmish ground, but did not have any long-term settlements in the state. An occasional buffalo could still be seen in the plat of Lincoln in the 1860s.[9]

Founding

[edit]

Lincoln was founded in 1856 as the village of Lancaster and became the county seat of the newly created Lancaster County in 1859.[10] The village was sited on the east bank of Salt Creek.[11] The first settlers were attracted to the area due to the abundance of salt. Once J. Sterling Morton developed his salt mines in Kansas, salt in the village was no longer a viable commodity.[12] Captain W. T. Donovan, a former steamer captain, and his family settled on Salt Creek in 1856. In 1859, the village settlers met to form a county. A caucus was formed and the committee, which included Donovan, selected Lancaster as the county seat. The county was named Lancaster. After the passage of the 1862 Homestead Act, homesteaders began to inhabit the area. The first plat was dated August 6, 1864.[9]

By the end of 1868, Lancaster had a population of approximately 500.[13] The township of Lancaster was renamed Lincoln, with the incorporation of the city of Lincoln on April 1, 1869. In 1869, the University of Nebraska was established in Lincoln by the state with a land grant of about 130,000 acres. Construction of University Hall, the first building, began the same year.[14]

State capital

[edit]

Nebraska was granted statehood on March 1, 1867. The capital of the Nebraska Territory had been Omaha since the creation of the territory in 1854. Most of its population lived south of the Platte River. After much of the territory south of the Platte was considered annexation to Kansas, the territorial legislature voted to place the capital south of the river and as far west as possible.[15] Before the vote to remove the capital from Omaha, Omaha Senator J. N. H. Patrick made a last-ditch effort to derail the move by having the future capital named after recently assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. Many of the people south of the Platte had been sympathetic to the Confederate cause in the recently concluded Civil War. It was assumed that senators south of the river would not vote to pass the measure if the future capital was named after Lincoln. In the end, the motion to name the future capital Lincoln was ineffective in blocking the measure and the vote to move the capital south of the Platte was successful, with the passage of the Removal Act in 1867.[16][17]

The Removal Act called for the formation of a Capital Commission to site the capital on state-owned land. On July 18, 1867, the Commission, composed of Governor David Butler, Secretary of State Thomas Kennard, and State Auditor John Gillespie, began to tour sites for the new capital. The village of Lancaster was chosen, in part due to its salt flats and marshes.[18][19][20] Lancaster had approximately 30 residents. Disregarding the original plat of the village of Lancaster, Kennard platted Lincoln on a broader scale. The plat of the village of Lancaster was not dissolved nor abandoned; it became Lincoln when the Lincoln plat files were finished on September 6, 1867.[21] To raise money for the construction of a capital, an auction of lots was held.[22]

Newcomers began to arrive and Lincoln's population grew. The Nebraska State Capitol was completed on December 1, 1868, a two-story building constructed with native limestone with a central cupola. The Kennard house, built in 1869, is the oldest remaining building in the original plat of Lincoln.[23]

In 1888, a new capitol building was constructed on the site of the first to replace the structurally unsound former capitol. The second building was a classical design by architect William H. Willcox.[24] Construction began on a third capitol building in 1922. Bertram G. Goodhue was selected in a national competition as its architect. By 1924, the first phase of construction was completed and state offices moved into the new building. In 1925, the Willcox-designed capitol building was razed. The Goodhue-designed capitol was constructed in four phases, with the completion of the fourth phase in 1932.[25] It is the second-tallest capitol building in the United States.[26]

Growth and expansion

[edit]The worldwide economic depression of 1890 saw Lincoln's population fall from 55,000 to 40,169 by 1900 (per the 1900 census). Volga-German immigrants from Russia settled in the North Bottoms neighborhood and as Lincoln expanded with the growth in population, the city began to annex nearby towns. Normal was the first town annexed in 1919.[27] Bethany Heights, incorporated in 1890, was annexed in 1922.[12] In 1926, the town of University Place was annexed.[28] College View, incorporated in 1892, was annexed in 1929. Union College, a Seventh Day Adventist institution, was founded in College View in 1891. In 1930, Lincoln annexed the town of Havelock. Havelock actively opposed annexation to Lincoln and only relented due to a strike by the Burlington railroad shop workers which halted progress and growth for the city.[12]

The Burlington and Missouri River Railroad's first train arrived in Lincoln on June 26, 1870, and the Midland Pacific (1871) and the Atchison and Nebraska (1872) soon followed. The Union Pacific began service in 1877. The Chicago and North Western and Missouri Pacific began service in 1886. The Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific extended service to Lincoln in 1892. Lincoln became a rail hub.[12]

As automobile travel became more common, so did the need for better roads in Nebraska and throughout the U.S. In 1911, the Omaha-Denver Trans-Continental Route Association, with support from the Good Roads Movement, established the Omaha-Lincoln-Denver Highway (O-L-D) through Lincoln. The goal was to have the most efficient highway for travel throughout Nebraska, from Omaha to Denver.[29]

In 1920, the Omaha-Denver Association merged with the Detroit-Lincoln-Denver Highway Association. As a result, the O-L-D was renamed the Detroit-Lincoln-Denver Highway (D-L-D) with the goal of having a continuous highway from Detroit to Denver. The goal was eventually realized by the mid-1920s; 1,700 mi (2,700 km) of constantly improved highway through six states.[30] The auto route's success in attracting tourists led entrepreneurs to build businesses and facilities in towns along the route to keep up with the demand. In 1924, the D-L-D was designated as Nebraska State Highway 6. In 1926, the highway became part of the Federal Highway System and was renumbered U.S. Route 38. In 1931, U.S. 38 was renumbered as a U.S. 6/U.S. 38 overlap and in 1933, the U.S. 38 route designation was dropped.[31][32]

In the early years of air travel, Lincoln had three airports and one airfield.[33] Union Airport, was established northeast of Lincoln in 1920. The Lincoln Flying School was founded by E.J. Sias in a building he built at 2145 O Street.[34] Charles Lindbergh was a student at the flying school in 1922. The flying school closed in 1947.[34] Some remnants of the Union Airport are still visible between N. 56th and N. 70th Streets, north of Fletcher Avenue; mangled within a slowly developing industrial zone.[35] Arrow Airport was established around 1925 as a manufacturing and test facility for Arrow Aircraft and Motors Corporation, primarily the Arrow Sport. The airfield was near Havelock; or to the west of where the North 48th Street Small Vehicle Transfer Station is today. Arrow Aircraft and Motors declared bankruptcy in 1939 and Arrow Airport closed roughly several decades later.[36] An Arrow Sport is on permanent display, hanging in the Lincoln Airport's main passenger terminal.[33][37]

As train, automobile, and air travel increased, business flourished and the city prospered. Lincoln's population increased 38.2% from 1920 to a population of 75,933 in 1930.[38] In 1930, the city's small municipal airfield was dedicated to Charles Lindbergh and named Lindbergh Field for a short period as another airfield was named Lindbergh in California. It was north of Salt Lake, in an area known over the years as Huskerville, Arnold Heights and Air Park; and was approximately within the western half of the West Lincoln Township.[39][40][41] The air field was a stop for United Airlines in 1927 and a mail stop in 1928.[42]

In 1942, the Lincoln Army Airfield was established at the site. During World War II, the U.S. Army used the facility to train over 25,000 aviation mechanics and process over 40,000 troopers for combat. The Army closed the base in 1945, but the Air Force reactivated it in 1952 during the Korean War. In 1966, after the Air Force closed the base, Lincoln annexed the airfield and the base's housing units.[39] The base became the Lincoln Municipal Airport, and later the Lincoln Airport, under the Lincoln Airport Authority's ownership. The two main airlines that served the airport were United Airlines and Frontier Airlines. The Authority shared facilities with the Nebraska National Guard, who continued to own parts of the old Air Force base.[43]

In 1966, Lincoln annexed the township of West Lincoln, incorporated in 1887. West Lincoln voters rejected Lincoln's annexation until the state legislature passed a bill in 1965 that allowed cities to annex surrounding areas without a vote.[44]

Revitalization and growth

[edit]

The downtown core retail district from 1959 to 1984 saw profound changes as retail shopping moved from downtown to the suburban Gateway Shopping Mall. In 1956, Bankers Life Insurance Company of Nebraska announced plans to build a $6 million shopping center next to their new campus on Lincoln's eastern outskirts. Gateway Shopping Center, now called Gateway Mall, opened at 60th and O streets in 1960.[45][46] By 1984, 75% of Lincoln's revenue from retail sales tax came from within a one-mile radius of the Mall. The exodus of retail and service businesses led the downtown core to decline and deteriorate.[47]

In 1969, the Nebraska legislature legislated laws for urban renewal. Soon afterward, Lincoln began a program of revitalization and beautification. Most of the urban renewal projects focused on downtown and the near South areas. Many ideas were considered and not implemented. Successes included Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, designed by Philip Johnson; new branch libraries, new street lighting, the First National Bank Building and the National Bank of Commerce Building designed by I.M. Pei.[48]

In 1971, an expansion of Gateway Mall was completed. 1974 marked a new assembly facility in Lincoln, a subsidiary of Kawasaki Heavy Industries in Japan to produce motorcycles for the North American market.[49] Lincoln's first woman mayor, Helen Boosalis, was elected in 1975. Mayor Boosalis was a strong supporter of the revitalization of Lincoln with the downtown beautification project being completed in 1978. In 1979, the square-block downtown Centrum was opened and connected to buildings with a skywalk. The Centrum was a two-level shopping mall with a garage for 1,038 cars. With the beautification and urban renewal projects, many historic buildings were razed in the city.[48] In 2007 and 2009, the city of Lincoln received beautification grants for improvements on O and West O Streets, west of the Harris Overpass, commemorating the history of the D-L-D.[30][50]

After the fall of Saigon in 1975, Vietnamese refugees created a large residential and business community along the 27th Street corridor alongside Mexican eateries and African markets.[51] Lincoln was designated as a "Refugee Friendly" city by the U.S. Department of State in the 1970s. In 2000, Lincoln was the twelfth-largest resettlement site per capita in the country.[52] As of 2011, Lincoln had the second largest Karen (Burmese ethnic minority) population in the United States (behind Omaha),[53][54] with an estimated 1,500 in 2019.[55] As of the same year, Nebraska was one of the largest resettlement sites for the people of Sudan, mostly in Lincoln and Omaha.[56] In 2014, some social service organizations estimated that up to 10,000 Iraqi refugees had resettled in Lincoln.[57][58] In recent years, Lincoln had the largest Yazidi (Iraqi ethnic minority) population in the U.S.,[59][60] with over 2,000–3,000 having settled within the city (as of late 2017).[61][62] In a three-year period, the immigrant and refugee student population at Lincoln Public Schools increased 52% - from 1,606 students in 2014, to 2,445 in 2017.[63]

The decade from 1990 to 2000 saw a significant rise in population from 191,972 to 225,581. North 27th Street and Cornhusker Highway were redeveloped with new housing and businesses built. The boom housing market in south Lincoln created new housing developments including high end housing in areas like Cripple Creek, Willamsburg and The Ridge. The shopping center Southpointe Pavilions was completed in competition of Gateway Mall.[64]

Into the 21st Century

[edit]

In 2001, Westfield America Trust purchased the Gateway Mall[65] and named it Westfield Shoppingtown Gateway. In 2005, the company renamed it the Westfield Gateway.[66] Westfield made a $45 million makeover of the mall in 2005 including an expanded food court, a new west-side entrance and installation of an Italian carousel.[67] In 2012, Westfield America Trust sold Westfield Gateway to Starwood Capital Group. Starwood reverted the mall's name from Westfield Gateway to Gateway Mall and has made incremental expansions and renovations.[65][68] In 2021, Gateway Mall was sold to a subsidiary of Strategic Value Partners.[69]

In 2015, ALLO Communications announced it would bring ultra-high speed fiber internet to the city. Speeds up to 1 Gigabit per second were available for business and households by building off of the city's existing fiber network. Construction on the citywide network began in March 2016 and was estimated to be complete by 2019,[70] making it one of the largest infrastructure projects in the United States.[71] Telephone and cable TV service were also included,[72] making it the third company to compete for such services within the same Lincoln footprint. In April 2016, Windstream Communications announced that 2,300 customers in Lincoln had 1 Gigabit per second fiber internet with an expected expansion of services to 25,000 customers by 2017.[73][74] On November 29, 2017, Lincoln was named a Smart Gigabit Community by U.S. Ignite Inc.[75][76] and in early 2018, Spectrum joined the ranks of internet service providers providing 1 gigabit internet within the city.[77]

In 2021, Lincoln's second-tallest skyscraper was completed downtown. Second in height to the State Capitol by law, the Lied Place Residences was 250 feet, or 20 floors.[78]. The Lied Place Residences surpassed the U.S. Bank Tower (formerly the First National Bank Building), completed in 1970, by 30 feet.[79] A least one taller building had been proposed since 2021, but any construction had been delayed due to inflation.[80][81]

In 2022, the City of Lincoln adopted a new flag, called "All Roads Lead to Lincoln".[82] In late 2022, Nebraska Highway 2 was diverted onto a newly constructed 11-mile long freeway, dubbed the South Beltway, on the Lincoln's south edge.[83] The realignment marked the first time the eastern segment of Nebraska 2 was largely outside of the city in its history. A planned upgrade of U.S. Highway 77 (a.k.a. the Homestead Expressway) to freeway standards was planned to begin in 2025.[84]

Geography

[edit]

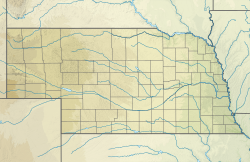

Lincoln has an area of 99.050 square miles (256.538 km2), of which 97.689 square miles (253.013 km2) is land and 1.361 square miles (3.525 km2) is water, according to the United States Census Bureau in 2020.[85]

Lincoln is one of the few large cities of Nebraska not along either the Platte River or the Missouri River. The city was originally laid out near Salt Creek and among the nearly flat saline wetlands of northern Lancaster County.[86] The city's growth has led to development of the surrounding land, much of which is composed of gently rolling hills. In recent years, Lincoln's northward growth has encroached on the habitat of the endangered Salt Creek tiger beetle.[87]

Metropolitan area

[edit]The Lincoln Metropolitan Statistical Area consists of Lancaster County and Seward County. Seward County was added to the metropolitan area in 2003. Lincoln is also in the Lincoln-Beatrice Combined Statistical Area which consists of the Lincoln metropolitan area and the micropolitan area of Beatrice. The city of Beatrice is the county seat of Gage County. The Lincoln-Beatrice combined statistical area is home to 363,733 people (2021 estimate)[6] making it the 104th-largest combined statistical area in the United States.[88]

Neighborhoods

[edit]

Lincoln's neighborhoods include both old and new development. Some neighborhoods in Lincoln were formerly small towns that Lincoln later annexed, including University Place in 1926, Belmont, Bethany (Bethany Heights) in 1922, College View in 1929, Havelock in 1930, and West Lincoln in 1966.[12] A number of Historic Districts are near downtown Lincoln, while newer neighborhoods have appeared primarily in the south and east.[89] As of December 2013, Lincoln had 45 registered neighborhood associations within the city limits.[90]

One core neighborhood that has seen rapid residential growth in recent years is the downtown Lincoln area. In 2010, there were 1,200 downtown Lincoln residents; in 2016, there were 3,000 (an increase of 140%).[91] Around the middle of the same decade, demand for housing and rent units began outpacing supply. With Lincoln's population expected to grow to more than 311,000 people by 2020, prices for homes and rent costs have risen. Home prices rose 10% from the first quarter of 2015 to the first quarter of 2016; rent prices rose 30% from 2007 to 2017 with a 5–8% increase in 2016 alone.[92][93]

Climate

[edit]

Located in the Great Plains far from the moderating influence of mountains or large bodies of water, Lincoln has a highly variable four season humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa, Trewartha Dcao): winters are cold and summers are hot.[94] With little precipitation during winter, precipitation is concentrated in the warmer months, when thunderstorms frequently roll in, often producing tornadoes. Snow averages 26.0 inches (66 cm) per season but seasonal accumulation has ranged from 7.2 in (18 cm) in 1967–1968 to 55.5 in (141 cm) in 2018–2019.[95] Snow tends to fall in light amounts, though blizzards are possible. There is an average of 38 days with a snow depth of 1 in (2.5 cm) or more. The average window for freezing temperatures is October 7 thru April 25, allowing a growing season of 164 days.[95]

The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 25.0 °F (−3.9 °C) in January to 78.1 °F (25.6 °C) in July. However, the city is subject both to episodes of bitter cold in winter and heat waves during summer, with 10.1 nights of 0 °F (−18 °C) or lower lows, 41.8 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs, and 3.5 days of 100 °F (38 °C)+ highs.[95] The city straddles the boundary of USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 5b and 6a.[96] Temperature extremes have ranged from −33 °F (−36.1 °C) on January 12, 1974, up to 115 °F (46.1 °C) on July 25, 1936.[95] Readings as high as 105 °F (41 °C) or as low as −20 °F (−29 °C) occur somewhat rarely; the last occurrence of each was August 24, 2023 and February 16, 2021.[95] The second lowest temperature ever recorded in Lincoln was −31 °F (−35.0 °C) on February 16, 2021, which broke the monthly record of −26 °F (−32.2 °C) last set a day earlier.[95] It occurred during the wider February 13–17, 2021 North American winter storm, which impacted the Midwestern and Northeastern United States as a whole.[97]

Based on 30-year averages obtained from NOAA's National Climatic Data Center for December, January and February, the Weather Channel ranked Lincoln the seventh-coldest major U.S. city in a 2014 article.[98] In 2014, the Lincoln-Beatrice area was among the "Cleanest U.S. Cities for Ozone Air Pollution" in the American Lung Association's "State of the Air 2014" report.[99]

| Climate data for Lincoln Airport, Nebraska, 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1887–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

83 (28) |

91 (33) |

97 (36) |

104 (40) |

108 (42) |

115 (46) |

110 (43) |

106 (41) |

98 (37) |

85 (29) |

75 (24) |

115 (46) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.9 (14.9) |

64.9 (18.3) |

77.9 (25.5) |

86.5 (30.3) |

91.9 (33.3) |

96.6 (35.9) |

100.1 (37.8) |

98.6 (37.0) |

94.6 (34.8) |

86.9 (30.5) |

73.4 (23.0) |

60.7 (15.9) |

101.7 (38.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 35.6 (2.0) |

40.6 (4.8) |

53.6 (12.0) |

64.8 (18.2) |

75.0 (23.9) |

85.2 (29.6) |

89.4 (31.9) |

87.2 (30.7) |

80.1 (26.7) |

66.6 (19.2) |

51.7 (10.9) |

39.4 (4.1) |

64.1 (17.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 25.0 (−3.9) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

41.2 (5.1) |

52.0 (11.1) |

63.1 (17.3) |

73.7 (23.2) |

78.1 (25.6) |

75.6 (24.2) |

67.2 (19.6) |

53.8 (12.1) |

39.8 (4.3) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

52.3 (11.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 14.4 (−9.8) |

18.4 (−7.6) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

39.2 (4.0) |

51.2 (10.7) |

62.1 (16.7) |

66.7 (19.3) |

64.1 (17.8) |

54.3 (12.4) |

41.0 (5.0) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

18.2 (−7.7) |

40.5 (4.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −7.7 (−22.1) |

−2.4 (−19.1) |

7.5 (−13.6) |

21.2 (−6.0) |

34.7 (1.5) |

47.9 (8.8) |

54.0 (12.2) |

51.2 (10.7) |

37.4 (3.0) |

22.7 (−5.2) |

10.7 (−11.8) |

−2.5 (−19.2) |

−11.7 (−24.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −33 (−36) |

−31 (−35) |

−19 (−28) |

3 (−16) |

24 (−4) |

39 (4) |

45 (7) |

39 (4) |

26 (−3) |

3 (−16) |

−15 (−26) |

−27 (−33) |

−33 (−36) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.73 (19) |

0.89 (23) |

1.55 (39) |

2.69 (68) |

4.91 (125) |

4.48 (114) |

3.25 (83) |

3.32 (84) |

2.90 (74) |

2.14 (54) |

1.30 (33) |

1.18 (30) |

29.34 (745) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.5 (17) |

7.1 (18) |

3.4 (8.6) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.9 (2.3) |

1.5 (3.8) |

5.3 (13) |

26.0 (66) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.9 | 6.1 | 8.1 | 9.7 | 11.8 | 10.4 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 95.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 5.0 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 3.8 | 17.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70.3 | 72.5 | 69.1 | 63.6 | 66.9 | 65.2 | 65.4 | 68.9 | 70.1 | 67.1 | 71.5 | 73.1 | 68.6 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 13.3 (−10.4) |

18.7 (−7.4) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

37.9 (3.3) |

50.2 (10.1) |

59.2 (15.1) |

64.2 (17.9) |

63.0 (17.2) |

54.1 (12.3) |

41.4 (5.2) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

17.1 (−8.3) |

39.7 (4.3) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 176.8 | 167.6 | 211.9 | 236.4 | 273.3 | 314.4 | 329.9 | 294.9 | 236.4 | 216.9 | 156.4 | 146.8 | 2,761.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 59 | 56 | 57 | 59 | 61 | 70 | 72 | 69 | 63 | 63 | 52 | 51 | 52 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[c][95][101][102] | |||||||||||||

On May 5, 2019, an EF2 tornado hit parts of western Lincoln, although no major injuries occurred.[103]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 2,441 | — | |

| 1880 | 13,003 | 432.7% | |

| 1890 | 55,164 | 324.2% | |

| 1900 | 40,169 | −27.2% | |

| 1910 | 43,973 | 9.5% | |

| 1920 | 54,948 | 25.0% | |

| 1930 | 75,933 | 38.2% | |

| 1940 | 81,984 | 8.0% | |

| 1950 | 98,884 | 20.6% | |

| 1960 | 128,521 | 30.0% | |

| 1970 | 149,518 | 16.3% | |

| 1980 | 171,932 | 15.0% | |

| 1990 | 191,972 | 11.7% | |

| 2000 | 225,581 | 17.5% | |

| 2010 | 258,379 | 14.5% | |

| 2020 | 291,082 | 12.7% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 294,757 | [4] | 1.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[104] | |||

Lincoln is Nebraska's second-most-populous city.[105] In the 1970s, The U.S. government designated Lincoln a refugee-friendly city due to its stable economy, educational institutions, and size. Since then, refugees from Vietnam settled in Lincoln, and more came from other countries.[106] In 2013, Lincoln was named one of the "Top Ten Most Welcoming Cities in America" by Welcoming America.[107][108]

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[109] | Pop 2010[110] | Pop 2020[111] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 198,087 | 214,739 | 222,749 | 87.81% | 83.11% | 76.52% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 6,803 | 9,541 | 13,224 | 3.02% | 3.69% | 4.54% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 1,354 | 1,611 | 1,644 | 0.60% | 0.62% | 0.56% |

| Asian (NH) | 7,006 | 9,711 | 13,765 | 3.11% | 3.76% | 4.73% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 127 | 128 | 162 | 0.06% | 0.05% | 0.06% |

| Some other race (NH) | 326 | 353 | 1,282 | 0.14% | 0.14% | 0.44% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 3,724 | 6,114 | 13,322 | 1.65% | 2.37% | 4.58% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 8,154 | 16,182 | 24,934 | 3.61% | 6.26% | 8.57% |

| Total | 225,581 | 258,379 | 291,082 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

The 2020 United States census[112] counted 291,082 people, 115,930 households, and 67,277 families in Lincoln. The population density was 2,937.6 per square mile (1,134.2/km2). There were 122,048 housing units at an average density of 1,231.7 per square mile (475.6/km2). The racial makeup was 78.66% (228,956) white, 4.67% (13,605) black or African-American, 0.89% (2,589) Native American, 4.77% (13,871) Asian, 0.07% (196) Pacific Islander, 3.5% (10,175) from other races, and 7.45% (21,690) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race was 7.0% (22,321) of the population.

Of the 115,930 households, 26.9% had children under the age of 18; 43.8% were married couples living together; 27.1% had a female householder with no husband present. 31.0% of households consisted of individuals and 9.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.4 and the average family size was 3.0.

21.9% of the population was under the age of 18, 15.7% from 18 to 24, 26.8% from 25 to 44, 20.8% from 45 to 64, and 13.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32.9 years. For every 100 females, the population had 100.8 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older, there were 99.4 males.

The 2016-2020 5-year American Community Survey[113] estimates show that the median household income was $60,063 (with a margin of error of +/- $1,248) and the median family income $79,395 (+/- $1,992). Males had a median income of $37,646 (+/- $1,251) versus $27,411 (+/- $805) for females. The median income for those above 16 years old was $31,869 (+/- $455). Approximately, 7.5% of families and 12.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.4% of those under the age of 18 and 6.2% of those ages 65 or over.

Economy

[edit]

Lincoln's economy is fairly typical of a mid-sized American city; most economic activity is derived from the service and manufacturing industries.[114] Government and the University of Nebraska are both large contributors to the local economy. Other prominent industries in Lincoln include finance, insurance, publishing, manufacturing, pharmaceutical, telecommunications, railroads,[115] high technology,[114] information technology, medical, education and truck transport.

For October 2021, the Lincoln Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) preliminary unemployment rate was 1.3% (not seasonally adjusted).[116] With a tight labor market, Lincoln has seen rapid wage growth. From the summer of 2014 to the summer of 2015, the average hourly pay for both public and private employees have increased by 11%. From October 2014 to October 2015, wages were also up by 8.4%.[117]

One of the largest employers is Bryan Health, which consists of two major hospitals and several large outpatient facilities across the city. Healthcare and medical jobs account for a large portion of Lincoln's employment: as of 2009, full-time healthcare employees in the city included 9,010 healthcare practitioners in technical occupations, 4,610 workers in healthcare support positions, 780 licensed and vocational nurses, and 150 medical and clinical laboratory technicians.[118]

Several national business were originally established in Lincoln; these include student lender Nelnet, Ameritas, Assurity, Fort Western Stores, CliffsNotes and HobbyTown USA. Several regional restaurant chains began in Lincoln, including Amigos/Kings Classic,[119] Runza Restaurants,[120] and Valentino's.[121]

The Lincoln area makes up a part of what is known as the greater Midwest Silicon Prairie.[122] The city is also a part of a rapidly growing craft brewing industry.[123] In 2013, Lincoln ranked no. 4 on Forbes's list of the Best Places for Business and Careers,[124] no. 1 on NerdWallet's Best Cities for Job Seekers in 2015,[125] and no. 2 on SmartAsset's Cities with the Best Work-life Balance in 2019.[126]

Principal employers

[edit]According to the city's 2023 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[127] the principal employers of the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | State of Nebraska | 8,300 |

| 2 | Lincoln Public Schools | 7,780 |

| 3 | University of Nebraska-Lincoln | 7,500 |

| 4 | Bryan Health | 4,900 |

| 5 | US Government | 3,300 |

| 6 | City of Lincoln | 2,766 |

| 7 | Kawasaki Motors Mfg. Corp. | 2,450 |

| 8 | Saint Elizabeth Regional Medical Center | 1,825 |

| 9 | B&R Stores, Inc. | 1,800 |

| 10 | Duncan Aviation | 1,750 |

| 11 | Madonna Rehabilitation Hospital | 1,500 |

| 12 | Burlington Northern Railroad | 1,450 |

Automotive and technology

[edit]1974 saw the establishment of a Kawasaki motorcycles assembly facility named the American Kawasaki Motors Corporation (KMC), to complete Japan-produced components into finished products for the North American market.[49][128] Incorporated in 1981, Kawasaki Motors Manufacturing Corp. (KMM) and assumed control of KMC. As of 2022, their webpresence named tallies "All-Terrain Vehicles, Utility Vehicles, Personal Watercraft, Recreation Utility Vehicles, and Passenger Rail Cars" as their range.[129][130]

Kawasaki is one of Lincoln's largest private employers with over 2,400 employees, and it has the largest square footage of manufacturing space. Newer product lines are rail cars and aircraft cargo doors.[131]

Military

[edit]The Nebraska Air and Army National Guard's Joint Force Headquarters are in Lincoln along with other major units of the Nebraska National Guard.[132] During the early years of the Cold War, the Lincoln Airport was the Lincoln Air Force Base;[133] the Nebraska Air National Guard and the Nebraska Army National Guard now have joint-use facilities with the Lincoln Airport.[134] Alongside the National Guard, the 55th Wing of Offutt Air Force Base was temporarily headquartered in Lincoln through September 2022.[135]

Arts and culture

[edit]

Since Pinnacle Bank Arena opened in 2013, Lincoln's music scene has grown to the point where it is sometimes called a "Music City".[136][137][138] Primary venues for live music include Pinnacle Bank Arena,[139] Bourbon Theatre, Duffy's Tavern, and the Zoo Bar. The Pla-Mor Ballroom is a classic Lincoln music and dance scene with its in-house Sandy Creek Band. Pinewood Bowl hosts a range of performances, from national music performances to local plays, during the summer.[140]

The Lied Center is a venue for national tours of Broadway productions, concert music, and guest lectures, and regularly features its resident orchestra, the Lincoln Symphony Orchestra.[141] Lincoln has several performing arts venues. Plays are staged by UNL students in the Temple Building;[142] community theater productions are held at the Lincoln Community Playhouse,[143] the Loft at The Mill, and the Haymarket Theater.

Lincoln has a growing number of arts galleries, including the Sheldon Museum of Art, Burkholder Project and Noyes Art Gallery.[144]

For movie viewing, Marcus Theatres owns 32 screens at four locations, and the University of Nebraska's Mary Riepma Ross Media Arts Center shows independent and foreign films.[145] Standalone cinemas in Lincoln include the Joyo Theatre and Rococo Theater. The Rococo Theater also hosts benefits and other engagements.[146] The downtown section of O Street is Lincoln's largest bar and nightclub district.[147] There is also the Bourbon Theatre, which is primarily used for bands in the metal rock and other related genres.

Lincoln is the hometown of Zager and Evans, known for their international hit record "In the Year 2525" (1969).[148] It is also the hometown of several notable musical groups, such as Remedy Drive, VOTA, For Against, Lullaby for the Working Class, Matthew Sweet, Dirtfedd, The Show is the Rainbow and Straight. Lincoln is home to Maroon 5 guitarist James Valentine.

In 2012, the city was listed among the 10 best places to retire in the United States by U.S. News & World Report.[149]

Annual cultural events

[edit]Annual events in Lincoln have come and gone throughout time, such as Band Day at the University of Nebraska's Lincoln campus[150] and the Star City Holiday Parade.[151] However, some events have never changed while new traditions have been created. Current annual cultural events in Lincoln include the Lincoln National Guard Marathon and Half-Marathon in May,[152] Celebrate Lincoln in early June,[153] the Uncle Sam Jam around July 3,[154] and Boo at the Zoo in October.[155] A locally popular event is the Haymarket Farmers' Market, running from May to October in the Historic Haymarket,[156] one of several farmers markets throughout the city.[157]

Tourism

[edit]Tourist attractions and activities include the Sunken Gardens,[158] basketball games at Pinnacle Bank Arena,[139] the Lincoln Children's Zoo, the dairy store at UNL's East Campus,[159] and Mueller Planetarium on the city campus.[160] The Nebraska State Capitol,[161] which is also the tallest building in Lincoln,[162] offers tours.

The Speedway Motors Museum of American Speed preserves, interprets, and displays physical items significant in racing and automotive history.[163] The National Museum of Roller Skating extends public knowledge of roller skating history and seeks to preserve its legacy for future generations.[164] In late 2016, Lincoln was ranked #3 on Lonely Planet's "Best in the U.S.," destinations to see in 2017 list.[165]

Library

[edit]The city's public library system is Lincoln City Libraries, which has eight branches.[166] Lincoln City Libraries circulates more than three million items per year to the residents of Lincoln and Lancaster County. Lincoln City Libraries is also home to Polley Music Library and the Jane Pope Geske Heritage Room of Nebraska authors.[166]

Sports

[edit]

Lincoln is home to the University of Nebraska's sports teams, the Cornhuskers. In total, the university fields 22 men's and women's teams in 14 NCAA Division I sports.[167] Nebraska football began play in 1890.[168] Of the 128 Division I-A football teams, Nebraska is one of nine to have won 900 or more games.[169] Notable coaches include Tom Osborne and Bob Devaney. Devaney coached from 1962 to 1972; the university's indoor arena, the Bob Devaney Sports Center, is named for him. Osborne coached from 1972 to 1997.

Other sports teams are the Nebraska Wesleyan Prairie Wolves, an NCAA Division III University;[170] the Lincoln Saltdogs, an American Association independent minor league baseball team;[171] the Lincoln Stars, a USHL junior ice hockey team;[172] and the No Coast Derby Girls, a member of the Women's Flat Track Derby Association.[173]

Lincoln Airpark hosts SCCA Solo Nationals each September.[174]

Parks and recreation

[edit]Lincoln has an extensive park system, with over 131 individual parks[175] connected by a 248 mi (399 km) system of recreational trails, a 2.3 mi (3.7 km) system of bike lanes and a 1.3 mi (2.1 km) system of cycle tracks.[176] The MoPac Trail is a bicycling, equestrian and walking trail built on an abandoned Missouri Pacific Railroad corridor which runs for 27 miles (43 km) from the University of Nebraska's Lincoln campus eastward to Wabash, Nebraska.[177]

Regional parks include Antelope Park from S. 23rd and "N" Streets to S. 33rd Street and Sheridan Boulevard,[178] Bicentennial Cascade Fountain,[179] Hamann Rose Garden,[180] Lincoln Children's Zoo,[181] Veterans Memorial Garden,[182] and Holmes Park at S. 70th Street and Normal Boulevard.[183] Pioneers Park includes the Pioneers Park Nature Center at S. Coddington Avenue and W. Calvert Streets.[184][185]

Community parks include Ballard Park, Bethany Park, Bowling Lake Park, Densmore Park, Erwin Peterson Park, Fleming Fields, Irvingdale Park, Mahoney Park, Max E. Roper Park, Oak Lake Park, Peter Pan Park, Pine Lake Park, Sawyer Snell Park, Seacrest Park, Tierra Briarhurst, University Place Park and Woods Park.[186]

Other notable parks include Iron Horse Park,[187] Lincoln Community Foundation Tower Square,[188] Nine Mile Prairie owned by the University of Nebraska Foundation,[189] Sunken Gardens,[158] Union Plaza,[190] and Wilderness Park.[191] Smaller neighborhood parks are scattered throughout the city.[186] Additionally, there are five public recreation centers, nine outdoor public pools and five public golf courses not including private facilities in Lincoln.[175]

Government

[edit]

Lincoln has a mayor–council government. The mayor and a seven-member city council are selected in nonpartisan elections. Four members are elected from city council districts; the remaining three members are elected at-large.[192] Lincoln's health, personnel, and planning departments are joint city/county agencies; most city and Lancaster County offices are in the County/City Building. The most recent city general election was held on May 4, 2021.[193]

Since Lincoln is the state capital, many Nebraska state and United States Government offices are in Lincoln. The city lies within the Lincoln Public Schools school district.[194] The Lincoln Fire and Rescue Department shoulders the city's fire fighting and emergency ambulatory services while private companies provide non-emergency medical transport[195] and volunteer fire fighting units support the city's outlying areas.[196]

Education

[edit]

Primary and secondary education

[edit]Lincoln Public Schools (LPS) is the public school district which includes the majority of the city limits.[197] It includes eight traditional high schools: Lincoln High, East, Northeast, Northwest, North Star, Southeast, Southwest, and Standing Bear. LPS is also home to special interest high school programs, including the Arts and Humanities Focus Program, the Bryan Community School, The Career Academy and the Science Focus Program (Zoo School). Other programs include the Pathfinder Education Program, the Yankee Hill Program[198] and the Lincoln Air Force JROTC.[199]

Some outerlying sections of Lincoln are in other school districts: Norris School District 160 and Waverly School District 145.[197]

There are several private parochial elementary and middle schools throughout the community.[200] Like Lincoln Public Schools, these schools are broken into districts, but most will allow attendance outside of boundary lines. Lincoln's private high schools are College View Academy, Lincoln Christian, Lincoln Lutheran, Parkview Christian School and Pius X High School.[200]

Colleges and universities

[edit]Lincoln has twelve colleges and universities. The University of Nebraska–Lincoln, the main campus of the University of Nebraska system, is the largest university in Nebraska, with 20,830 undergraduate, 4,426 postgraduate students and 564 professionals enrolled in 2018. Out of the 25,820 enrolled, 2,187 undergraduate and 1,040 postgraduate students/professionals were international. With 135 countries outside of the U.S. represented, the five countries with the highest international enrollment were China, India, Malaysia, Oman and Rwanda.[201]

Nebraska Wesleyan University, as of 2020, has 1,924 undergraduate and 151 postgraduate students.[202] The school teaches in the tradition of a liberal arts college education. Nebraska Wesleyan was ranked the #1 liberal arts college in Nebraska by U.S. News & World Report in 2002. In 2009, Forbes ranked it 84th of America's Best Colleges.[203] It remains affiliated with the United Methodist Church.[204] Union Adventist University is a private Seventh-day Adventist four-year coeducational college with 911 students enrolled 2013–14.[205][206]

Bryan College of Health Sciences offers undergraduate degrees in nursing and other health professions; a Masters in Nursing; a Doctoral degree in nurse anesthesia practice, as well as certificate programs for ancillary health professions.[207] Universities with satellite locations in Lincoln are Bellevue University,[208] Concordia University (Nebraska)[209] and Doane University.[210] Lincoln also hosts the College of Hair Design and Joseph's College of Cosmetology.[211][212]

Southeast Community College is a community college system in southeastern Nebraska, with three campuses in Lincoln and an enrollment of 9,505 students as of spring 2024. The two-year Academic Transfer program is popular among students who want to complete their general education requirements before they enroll in a four-year institution. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln is the most popular transfer location.[213][214]

Media

[edit]

Television

[edit]Lincoln has four licensed broadcast full power television stations; and one serving the city, but licensed to an area outside its limits:[215]

- KSNB-TV (Channel 4; 4.1 DT) - NBC/MyNetworkTV affiliate[216]

- Ion Television affiliate 4.3

- KLKN (Channel 8; 8.1 DT) – ABC affiliate

- KOLN (Channel 10; 10.1 DT) – CBS affiliate

- KUON (Channel 12; 12.1 DT) – PBS affiliate, Nebraska Public Media Television flagship station

- KFXL (Channel 15; 51.1 DT) – Fox affiliate

The headquarters of Nebraska Public Media, which is affiliated with the Public Broadcasting Service and National Public Radio, are in Lincoln.[220] The city has two low power digital TV stations in Lincoln area: including the translator KFDY-LD (simulcast of (KOHA-LD)) owned by Flood Communications of Nebraska LLC, including for main Spanish-language network affiliate Telemundo on 27.1, NCN (Ind.) on 27.2, and religious network affiliate 3ABN on 27.3 in Lincoln area only, on virtual channel 27, digital channel 27; and another low power digital KCWH-LD on CW+ affiliate, owned by Gray on channel 18.1 included sub-channels like Ion on 18.2, and CBS (Simulcast of KOLN) on 18.3.[215]

Radio

[edit]

There are 18 radio stations licensed in Lincoln, not including radio stations licensed outside of the city that serve the Lincoln area. Most areas of Lincoln also receive radio signals from Omaha and other surrounding communities.

- KLCV (88.5) – Religious talk

- KZUM (89.3) – Independent Community Radio

- KRNU (90.3) – Alternative / College radio UNL

- KUCV (91.1) – National Public Radio

- K220GT (91.9) – Contemporary Christian

- K233AN (94.5) – Top 40

- KNNA-LP (95.7) – Christian

- K255CS (98.9) – Christian

- KFOR (101.5) – News/Talk

- KLMS (103.3) – Hot AC

- KLNC (105.3) – Classic Rock

- KFRX (106.3) – Top-40

- K294DJ (106.7) – Christian

- KBBK (107.3) – Hot AC

- KJTM-LP (107.9) – Contemporary Christian

The Lincoln Journal Star is the city's major daily newspaper.[223] The Daily Nebraskan is the official monthly magazine of the University of Nebraska's Lincoln campus and The DailyER is the university's biweekly satirical paper.[224][225] Other university newspapers include the Reveille, the official periodical campus paper of Nebraska Wesleyan University and the Clocktower, the official weekly campus paper of Union College.[226][227]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]Major highways

[edit]Lincoln is served by Interstate 80 via seven interchanges, connecting the city to San Francisco in the west and Teaneck, New Jersey in the New York City metropolitan area in the east.[228] Other Highways that serve the Lincoln area are Interstate 180, U.S. Route 6, U.S. Highway 34, U.S. Highway 77 and nearby Nebraska Highway 79. The eastern segment of Nebraska Highway 2 is a primary trucking route that connects the Kansas City metropolitan area (Interstate 29) to the I-80 corridor in Lincoln.[229] A few additional minor State Highway segments are located within the city as well.[230]

Mass transit

[edit]A public bus transit system, StarTran, operates in Lincoln. StarTran's fleet consists of 67 full-sized buses and 13 Handi-Vans. The transit system has 18 bus routes, with a circular bus route downtown. Annual ridership for the fiscal year 2017–18 was 2,463,799.[231]

StarTran also offers a door-to-door van service called VANLNK to customers with the mobile app. The service has vehicles that are smaller than StarTran's buses. Departures can only be in the Lincoln city limits, and the service is a shared-ride service, meaning it optimizes trips to carry people along routes on the same schedule. All VANLNK vehicles are accessible by disabled people using lifts and ramps. However, although service animals are allowed, non-service animals must be on a pet carrier.[232]

Intercity transit

[edit]

The Lincoln Airport (KLNK/LNK) provides passengers with daily non-stop service to Chicago O'Hare International Airport, and Denver International Airport. General aviation support is provided through several private aviation companies.[233] The Lincoln Airport was among the emergency landing sites for the NASA Space Shuttle.[234] The site was chosen chiefly because of a 12,901 feet (3,932 m) runway; the longest of three at the airport.[235]

Lincoln is served by both Express Arrow and Burlington Trailways for regional bus service between Omaha, Denver and points beyond.[236][237] Megabus, in partnership with Windstar Lines, provides bus service between Lincoln and Chicago with stops in Omaha, Des Moines, Iowa City and Moline.[238]

Amtrak provides service to Lincoln station, operating its California Zephyr daily in each direction between Chicago and Emeryville, California, using BNSF's Lincoln – Denver route through Nebraska.[239] The city is an Amtrak crew-change point.[240]

Rail freight

[edit]Rail freight travels coast-to-coast, to and through Lincoln via BNSF Railway, the Union Pacific Railroad, Lincoln's own Omaha, Lincoln and Beatrice Railway Company and an Omaha Public Power District rail line.[241][242] Lincoln was once served by the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad (Rock Island), the Missouri Pacific Railroad (MoPac) and the Chicago and North Western Transportation Company (C&NW). The abandoned right-of-way of these former railroads have since been turned into bicycle trails.[243]

Cycling modes

[edit]Lincoln has a third-generation dock-based bike share program that began in mid-April 2018, called BikeLNK. The first phase of the program included 19 docks and 100 bicycles, scattered throughout downtown and around the UNL City, UNL East & Nebraska Innovation campuses.[244] A second phase in 2019 increased the number of docks to 21, total bicycles to 105 and expanded to a location outside of downtown.[245] Lincoln also has a fleet of commercial pedicabs that operates in the downtown area.[246]

Modal characteristics

[edit]In 2016, 80.5 percent of working Lincoln residents commuted by driving alone, 9.6 percent carpooled, 1.1 percent used public transportation, and 3.1 percent walked. About 2.4 percent used all other forms of transportation, including taxis, bicycles, and motorcycles as well as ride-sharing services such as Lyft and Uber which entered the Lincoln market in the summer of 2014. About 3.3 percent worked at home.[247]

In 2015, 6.3 percent of city of Lincoln households were without a car, which decreased slightly to 5.8 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Lincoln averaged 1.78 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8 per household.[248]

Utilities

[edit]Power in Lincoln is provided by the Lincoln Electric System (LES). The LES service area covers 200 square miles (520 km2), serving Lincoln and several other communities outside of the city. A public utility,[249] LES's electric rates are the 8th lowest in the nation, according to a nationwide survey conducted by LES in 2018.[250] Current LES power supply resources are 35% oil and gas, 34% renewable and 31% coal.[251] Renewable resources have increased with partial help from the addition of an LES-owned five Megawatt solar energy farm put into service June, 2016.[252] The solar farm produces enough energy to power 900 homes.[253] LES also owns two wind turbines in the northeast part of the city.[254]

Water in Lincoln is provided through the Lincoln Water System.[255] In the 1920s, the city of Lincoln undertook the task of building the Lincoln Municipal Lighting and Waterworks Plant (designed by Fiske & Meginnis). The building worked as the main hub for water from nearby wells and power in Lincoln for decades until it was replaced and turned into an apartment building.[256] Most of Lincoln's water originates from wells along the Platte River near Ashland, Nebraska.[257] Wastewater is in turn collected by the Lincoln Wastewater System. The city of Lincoln owns both systems.[258]

Natural gas is provided by Black Hills Energy.[259]

Landline telephone service has had a storied history within the regional Lincoln area with the Lincoln Telephone & Telegraph Company, founded in 1880. In its history, LT&T introduced the first rotary dial telephone exchange in the U.S. in 1904; the first Radiotelephone in 1946; and piloted the first 911 system in the nation in 1968.[260] Many years later, LT&T was renamed Aliant Communications and shortly thereafter merged in 1998 with Alltel.[261] In 2006, Windstream Communications was formed with the spinoff of Alltel and a merge with VALOR Communications Group.[262] Windstream Communications provides telephone service both over VoIP and conventional telephone circuits to the Lincoln area.[263] Spectrum[264] offers telephone service over VoIP on their cable network.[265][266] In addition, ALLO Communications provides telephone, television and internet service over their underground fiber network to all parts of the city.[267][268]

Health care

[edit]Lincoln has three major hospitals within two health care systems serving the city: Bryan Health and CHI Health St. Elizabeth. Madonna Rehabilitation Hospital is a geriatric facility and a physical medicine & rehabilitation center. Lincoln has two specialty hospitals: Lincoln Surgical Hospital[269] and the Nebraska Heart Institute.[270] A U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) is in Lincoln (Lincoln VA Clinic, part of the Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System).[271]

Police

[edit]The Lincoln Police Department has just over 350 police officers. The police per capita rate is extremely low at 1.2 officers per 1,000 people (the average being 1.94), and the violent crime rate of 522 per 100,000 people. The department is nationally accredited by the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies and was the first law enforcement agency in Nebraska to become so. The LPD shares its headquarters with the Lancaster County Sheriff's Office.[citation needed]

In popular culture

[edit]In April 2011, a contest held by DC Comics selected Omaha, Nebraska, as the site of a new issue. However, the Nebraska State Capitol was depicted in the issue, with the writers having confused Lincoln for Omaha.[272]

See also

[edit]- Charles Starkweather

- List of people from Lincoln, Nebraska

- List of mayors of Lincoln, Nebraska

- History of Lincoln, Nebraska

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Mean maxima and minima (i.e., the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Official records for Lincoln kept at University of Nebraska–Lincoln (Weather Bureau) from January 1887 to December 1947, Lincoln Municipal Airport from January 1948 to June 1954, Lincoln University (campus) from July 1954 to August 1955, the Weather Bureau in downtown from September 1955 to August 1972, and at Lincoln Municipal Airport since September 1972.[100]

- ^ Only 20 to 22 years of data were used to calculate relative humidity normals.

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Campus Guide: Lincoln lexicon". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. August 22, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ a b "Geographic Names Information System". edits.nationalmap.gov. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "QuickFacts -- Lincoln city, Nebraska; United States". U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. July 1, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Lincoln, NE (MSA)". Federal Reserve Economic Data. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

- ^ a b "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020-2021 -- Annual Resident Population Estimates and Estimated Components of Resident Population Change for Combined Statistical Areas and Their Geographic Components: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2021 (CSA-EST2021-ALLDATA)". U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. July 1, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population in the United States and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2021 -- Metropolitan Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico (CBSA-MET-EST2021-POP)". U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. July 1, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "List of 2020 Census Urban Areas". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "1889 History of Lincoln Nebraska – Chapter 11". Memorial Library. CFC Productions. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "Counties and County Seats by License Place Prefix Numbers". Nebraska Databook. Nebraska Department of Economic Development. June 8, 2010. Archived from the original on October 20, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Lincoln Bar Association (May 1, 1970). "County-City Building, Lincoln, Lancaster County, Nebraska". Nebraska State Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 2, 2004. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Lincoln — Lancaster County". Virtual Nebraska. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "1889 History of Lincoln Nebraska – Chapter 12". Memorial Library. CFC Productions. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Hays & Cox, p. 234.

- ^ Hays & Cox, p. 29.

- ^ "More about Nebraska statehood, the location of the capital, and the story of the commissioner's home". Nebraska State Historical Society. March 20, 2000. Archived from the original on January 21, 2001. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ "Lincoln, Nebraska, United States". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ "Lincoln's Founding". Nebraska State Historical Society. January 11, 2006. Archived from the original on November 15, 2006. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "Lincoln: History". City-Data.com. Advameg, Inc. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ McGee, Jim (February 13, 2022). "Jim McKee: The birth of Antelope Park in Lincoln". Norfolk Daily News. Norfolk, NE. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ McKee2, p. 95.

- ^ Hays & Cox, p. 349.

- ^ "More About Nebraska Statehood". Nebraska State Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 21, 2001. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "History of Nebraska's Capitols". Nebraska State Capitol. Nebraska Capitol Commission. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ Walton, Don (February 10, 2015). "Capitol may need earthquake evaluation". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Hill, Kori (November 4, 2015). "Assassinations, fires, and domes: 50 facts about 50 state capitol buildings". Travel. USA Today (Experience America ed.). Fairfax County, VA: Gannett Company. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ McKee, Jim (December 30, 2017). "Jim McKee: Traversing Lincoln via interurban railroads". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ Zimmer, Edward. "Lincoln – Lancaster County". Virtual Nebraska – Nebraska ... Our Towns. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ^ Ashland Historical Society; Huebinger, M. (October 12, 2013). "Huebinger's Map & Guide for Omaha-Denver Transcontinental Route (condensed, edited & annotated edition)" (PDF). Ashland Historical Society / Saline Ford Historical Preservation Society, Nebraska. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ a b "Detroit, Lincoln and Denver (DLD) Highway". Iowa Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Mead & Hunt, Inc.; Heritage Research, Ltd. (August 2002). Jacobson, Kent A. (ed.). "Nebraska Historic Highway Survey" (PDF). Nebraska Department of Roads. Nebraska State Historical Society / Nebraska Department of Roads. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ Weingroff, Richard F. (November 18, 2015). "U.S. 6 – The Grand Army of the Republic Highway". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration. U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "Lincoln's Aviation Past". The Lincoln Air Force Base Online Museum. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ a b McKee, p. 116.

- ^ Freeman, Paul (June 4, 2016). "Union Airport, Lincoln, NE". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields. p. Northeastern Nebraska. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Arrow Aircraft and Motor Corporation (Lincoln, Neb.)". Nebraska State Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ^ "Nebraska Trailblazer No 18 – Aviation in Nebraska" (PDF). Nebraska State Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ^ "Population of Nebraska Incorporated Places, 1930 to 1980". Nebraska Possibilities Endless. Nebraska Department of Economic Development Agency. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ a b McKee, Jim (February 10, 2013). "Jim McKee: From Lincoln airport to Lincoln neighborhood". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ "Nebraska Trailblazer, Aviation in Nebraska" (PDF). Nebraska History.org. Nebraska State Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ^ Freeman, Paul. "Abandoned & Little-Known Air Fields". Air Fields. Paul Freeman. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ^ Branting, Robb. "History". The Lincoln Air Force Base Online Museum. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ^ "Fact Sheet – History of the Nebraska Air National Guard" (PDF). 155arw.ang.af.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ^ McKee, Jim (March 5, 2016). "Jim McKee: West Lincoln almost an industrial success". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ "We're shopping for memories of Hovland-Swanson". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. April 13, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ "Gateway Mall emerged where cornfield had existed". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. January 6, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ McKee, p. 125.

- ^ a b McKee, pp. 125–128.

- ^ a b Kawasaki's US factory. Motorcycle News, 13 February 1974, p.7. Retrieved March 14, 2022

- ^ "Lincoln West "O" Historic Highway Project" (PDF). City of Lincoln, Nebraska. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ^ Calvan, Bobby Caina (June 18, 2014). "How Asian Immigration Is Changing America's Heartland". Asian America. NBC News. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "History of New Americans Task Force". City of Lincoln, Nebraska. Archived from the original on June 11, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ Kemmet, Kay (July 13, 2011). "Workshop gives insight into Karen culture". Grand Island Independent. Grand Island, NE. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ "Karen Society of Nebraska, Inc". Karen Society of Nebraska. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ Lange-Kubicek, Cindy (July 7, 2019). "Members of Karen community come together for garden with taste of home". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Pascale, Jordan (January 14, 2011). "Thousands of Sudanese make pilgrimage to Omaha". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ Knapp, Fred (August 15, 2014). "Yazidis And Other Iraqis In Lincoln Offer Different Perspectives On Crisis". Lincoln, NE. NET Radio. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ Knapp, Fred (December 12, 2017). "Iraqis A Fast-Growing Group In Nebraska". Lincoln, NE. NET Radio. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ Siemaszko, Corky (November 26, 2015). "Yazidis in U.S. Grateful This Thanksgiving for Escaping ISIS". NBC News. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ^ Smith, Mitch (September 7, 2015). "Yazidis Settle in Nebraska, but Roots Run Deep in Iraq". New York Times. New York, NY. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ Williams, Jack (December 14, 2017). "Yazidis From Iraq Find Welcome Refuge In Nebraska". Lincoln, NE. NET Radio. Archived from the original on December 11, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ Case, Emily (July 23, 2018). "New downtown Lincoln Mediterranean market offers varied selection". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ Reist, Margaret (June 4, 2017). "LPS strengthens trauma program to help refugee students". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ McKee2, p. 14.

- ^ a b "Gateway history". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. April 18, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (June 1, 2005). "Gateway a 'shoppingtown' no more". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (September 26, 2005). "Westfield Gateway unveils new amenities, food court". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (April 18, 2012). "Gateway mall sold". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ "Gateway Mall sold for $51.5 million". Lincoln, NE. KOLN/KGIN-TV (10/11) News. May 23, 2022. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (November 17, 2015). "Ultra-fast Internet service is coming to Lincoln". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ Johnson, Riley (December 2, 2017). "In Allo's rapid digging, city and utilities encounter growing pains". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Hicks, Nancy (December 7, 2015). "ALLO gets praise for bringing super fast Internet service to Lincoln". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (December 18, 2015). "Windstream bringing 1 gigabit Internet to Lincoln". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (April 4, 2016). "Windstream debuts 1G internet in Lincoln". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (December 11, 2017). "Lincoln now a Smart Gigabit Community". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Mohan, Nishal (November 29, 2017). "US Ignite, Inc. Announces Lincoln, Nebraska will Join Rapidly Growing Network of Smart Gigabit Communities". US Ignite. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (April 25, 2018). "Charter now offering 1-gig internet in Lincoln, Southeast Nebraska". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (August 4, 2021). "Topped-out Lied Place Residences in line for more TIF money". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (November 7, 2021). "Downtown Lincoln's tallest office building has new owner". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (November 13, 2023). "Planned downtown Lincoln skyscraper would grow taller than Lied Place". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ^ Sangimino, Patt (October 5, 2023). "Lincoln Bold on hold until interest rates make project more feasible". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ "City Flag". www.lincoln.ne.gov. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Knapp, Fred (December 14, 2022). "Lincoln South Beltway project opens, helped by creative financing". Lincoln, NE. Nebraska Public Media. Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ^ Reist, Margaret (April 7, 2024). "NDOT plans to add freeway interchanges to U.S. 77 West Bypass in Lincoln". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ^ "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ "Resource Categorization of Nebraska's Eastern Saline Wetlands" (PDF). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Nebraska Game U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Parks Commission, Nebraska Department of Environmental Quality, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ "Endangered Species of the Mountain-Prairie Region – U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "OMB BULLETIN NO. 15-01" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2016 – via National Archives.

- ^ "lincoln.ne.gov – Planning Department – Long Range Planning – Historic Preservation – Sites and Districts". City of Lincoln, Nebraska. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ "lincoln.ne.gov – Urban Development – Neighborhood Statistics". City of Lincoln, Nebraska. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (June 17, 2016). "Biz Bits: DLA may soon stand for Downtown 'Living' Association". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (May 8, 2016). "Lincoln home prices hitting once unthinkable levels". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ^ Harris, Brandi B. (July 7, 2017). "More people and needs means higher rent". Lincoln, NE. KOLN/KGIN-TV (10/11) News. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ^ "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Updated Map for the United States of America". Institute for Veterinary Public Health. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Weather Service Forecast Office. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ "What is my arborday.org Hardiness Zone?". Arbor Day Foundation. Archived from the original on February 5, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ^ Goldberg, Brad Brooks, Barbara (February 17, 2021). "Texas deep freeze leaves millions without power, 21 dead". Reuters. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Laukaitis, Algis (January 10, 2014). "How cold is it? Lincoln ranks 7th coldest in nation". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ "State of the Air 2014" (PDF). American Lung Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 30, 2014. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ "Threaded Station Extremes". ThreadEx. NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) and the National Weather Service (NWS), the Northeast Regional Climate Center (NRCC). Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for LINCOLN/MUNICIPAL ARPT NE 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "May 5, 2019: EF-2 Tornado Confirmed in Lincoln". www.weather.gov. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "Population of Nebraska Incorporated Places". Nebraska Databook. Nebraska Department of Economic Development. March 9, 2015. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Burleigh, Nina (October 10, 2010). "We've Found Peace in This Land". Parade (Parade Digital ed.). Athlon Media Group. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ Pascale, Jordan (June 21, 2013). "Lincoln designated Welcoming City for immigrants". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ "Welcoming Cities and Counties". Welcoming America. Archived from the original on April 11, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Lincoln city, Nebraska". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Lincoln city, Nebraska". United States Census Bureau .

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Lincoln city, Nebraska". United States Census Bureau .

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ a b Schaper, David (March 2, 2015). "A Nearly Recession-Proof City Is Not Slowing Down" (Morning ed.). National Public Radio. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ "Revised Specifications 2014 Transit Development Plan City Of Lincoln, Nebraska – Startran Request For Proposals" (PDF). City of Lincoln, Nebraska. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "Labor Area Summary, Lincoln MSA" (PDF). Nebraska INFOlink. Nebraska Department of Labor. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Sparshott, Jeffrey (December 17, 2015). "In Lincoln, Neb., a View of Full Employment". Wall Street Journal. New York, NY: Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ "Lincoln Career, Salary & Employment Info". College Degree Report. Archived from the original on October 8, 2010.

- ^ "About Us – Amigos/Kings Classic". Amigos/Kings Classic. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- ^ "History - Runza". Runza.com. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ "Valentino's – History". Valentino's of America, Inc. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- ^ Pendell, Ryan (September 30, 2015). "7 reasons why you should pay attention to Lincoln". Silicon Prairie News. Silicon Prairie News & Destination Graphic. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ Olberding, Matt (May 22, 2017). "Local tourism promotion focusing on craft beer". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ^ Badenhausen, Kurt (August 7, 2013). "Des Moines Tops List Of The Best Places For Business And Careers". Forbes. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ Jasthi, Sreekar (January 12, 2015). "Best Cities for Job Seekers in 2015". nerdwallet. NerdWallet, Inc. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ Miller, CEPF, Derek (January 23, 2019). "Cities With the Best Work-Life Balance – 2019 Edition". SmartAsset. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the City of Lincoln, Nebraska, for the Fiscal Year Ended August 31, 2023" (PDF). Accounting Division of the Finance Department. InterLinc. City of Lincoln, Nebraska. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Kawasaki's Plant in Lincoln, Nebraska cycleworld.com, July 11, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2022

- ^ Kawasaki Plans $200M Expansion That Would Add 550 New Jobs U.S. News & World Report, July 19, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2022

- ^ Welcome to Kawasaki Motors Manufacturing Corp., U.S.A. kawasakilincoln.com Retrieved March 11, 2022

- ^ Kawasaki to expand in Lincoln, add hundreds of jobs Lincoln Journal Star, February 7, 2022. Retrieved March 14, 2022

- ^ "Nebraska National Guard – About Us". Nebraska National Guard. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ^ "The History of the Former Lincoln Air Force Base". lincolnafb.org. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "Lincoln Air National Guard Base". Military Bases US. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Hammack, Zach (April 16, 2021). "Officials welcome Offutt planes to temporary home -- 'Lincoln Air Force Base'". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Bragg, Meghan (February 16, 2016). "Lincoln's Music Scene Continues to Grow". Lincoln, NE. KOLN/KGIN-TV (10/11) News. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Wolgamott, L. Kent (December 14, 2016). "On the Beat: Music scene puts Lincoln on top destinations list". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Wolgamott, L. Kent (January 2, 2020). "Lincoln's live-music scene: 'When you've got great venues, things fall into place'". Lincoln Journal Star. Lincoln, NE. Retrieved January 20, 2020.