Spasmodic torticollis

| Spasmodic torticollis | |

|---|---|

| |

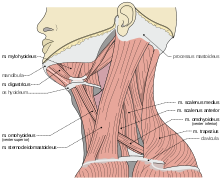

| Muscles of the neck | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Spasmodic torticollis is an extremely painful chronic neurological movement disorder causing the neck to involuntarily turn to the left, right, upwards, and/or downwards. The condition is also referred to as "cervical dystonia". Both agonist and antagonist muscles contract simultaneously during dystonic movement.[1] Causes of the disorder are predominantly idiopathic. A small number of patients develop the disorder as a result of another disorder or disease. Most patients first experience symptoms midlife. The most common treatment for spasmodic torticollis is the use of botulinum toxin type A.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Initial symptoms of spasmodic torticollis are usually mild. Some feel an invisible tremor of their head for a few months at onset. Then the head may turn, pull or tilt in jerky movements, or sustain a prolonged position involuntarily. Over time, the involuntary spasm of the neck muscles will increase in frequency and strength until it reaches a plateau. Symptoms can also worsen while the patient is walking or during periods of increased stress. Other symptoms include muscle hypertrophy, neck pain, dysarthria and tremor.[2] Studies have shown that over 75% of patients report neck pain,[1] and 33% to 40% experience tremor of the head.[3]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

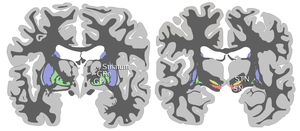

The pathophysiology of spasmodic torticollis is still relatively unknown. Spasmodic torticollis is considered neurochemical in nature, and does not result in structural neurodegenerative changes. Although no lesions are present in the basal ganglia in primary spasmodic torticollis, fMRI and PET studies have shown abnormalities of the basal ganglia and hyper activation of the cortical areas.[4] Studies have suggested that there is a functional imbalance in the striatal control of the globus pallidus, specifically the substantia nigra pars reticulata. The studies hypothesize the hyper activation of the cortical areas is due to reduced pallidal inhibition of the thalamus, leading to over activity of the medial and prefrontal cortical areas and under activity of the primary motor cortex during movement.[5] It has also been suggested that the functional imbalance is due to an imbalance of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, acetylcholine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid. These neurotransmitters are secreted from the basal ganglia, traveling to muscle groups in the neck. An increase in neurotransmitters causes spasms to occur in the neck, resulting in spasmodic torticollis.[6] Studies of local field potentials have also shown an increase of 4–10 Hz oscillatory activity in the globus pallidus internus during myoclonic episodes and an increase of 5–7 Hz activity in dystonic muscles when compared to other primary dystonias. This indicates that oscillatory activity in these frequency bands may be involved in the pathophysiology of spasmodic torticollis.[7]

Diagnosis

[edit]The most commonly used scale to rate the severity of spasmodic torticollis is the Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale (TWSTRS). It has been shown that this rating system has widespread acceptance for use in clinical trials, and has been shown to have “good interobserver reliability.”[8] There are three scales in the TWSTRS: torticollis severity scale, disability scale, and pain scale. These scales are used to represent the severity, the pain, and the general lifestyle of spasmodic torticollis.[citation needed]

Classification

[edit]Spasmodic torticollis is a form of focal dystonia, a neuromuscular disorder that consists of sustained muscle contractions causing repetitive and twisting movements and abnormal postures in a single body region.[9] There are two main ways to categorize spasmodic torticollis: age of onset, and cause. The disorder is categorized as early onset if the patient is diagnosed before the age of 27, and late onset thereafter. The causes are categorized as either primary (idiopathic) or secondary (symptomatic). Spasmodic torticollis can be further categorized by the direction and rotation of head movement.[citation needed]

Primary

[edit]Primary spasmodic torticollis is defined as having no other abnormality other than dystonic movement and occasional tremor in the neck.[1] This type of spasmodic torticollis is usually inherited. Studies have shown that the DYT7 locus on chromosome 18p in a German family and the DYT13 locus on chromosome 1p36 in an Italian family is associated with spasmodic torticollis. The inheritance for both loci is autosomal dominant. These loci are all autosomal dominantly inherited with reduced penetrance. Although these loci have been found, it is still not clear the extent of influence the loci have on spasmodic torticollis.[6]

Secondary

[edit]When other conditions lead to spasmodic torticollis, it is said that the spasmodic torticollis is secondary. A variety of conditions can cause brain injury, from external factors to diseases. These conditions are listed below:[1]

- Central nervous system tumor

- Central pontine myelinolysis

- Cerebrovascular diseases

- Drug induced

- Infectious or post infectious encephalopathies

- Kernicterus

- Metabolic

- Paraneoplastic syndromes

- Perinatal (during birth) cerebral injury

- Peripheral or central trauma

- Toxins

Secondary spasmodic torticollis is diagnosed when any of the following are present: history of exogenous insult or exposure, neurological abnormalities other than dystonia, abnormalities on brain imaging, particularly in the basal ganglia.[1]

Head positions

[edit]To further classify spasmodic torticollis, one can note the position of the head.

- Torticollis is the horizontal turning (rotational collis) of the head, and uses the ipsilateral splenius, and contralateral sternocleidomastoid muscles. This is the "chin-to-shoulder" version.

- Laterocollis is the tilting of the head from side to side. This is the "ear-to-shoulder" version. This involves many more muscles: ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid, ipsilateral splenius, ipsilateral scalene complex, ipsilateral levator scapulae, and ipsilateral posterior paravertebrals.

- The flexion of the neck (head tilts forwards) is anterocollis. This is the "chin-to-chest" version and is the most difficult version to address. This movement utilizes the bilateral sternocleidomastoid, bilateral scalene complex, bilateral submental complex.

- Retrocollis is the extension of the neck (head tilts back) and uses the following muscles for movement: bilateral splenius, bilateral upper trapezius, bilateral deep posterior paravertebrals. This is the "chin-in-the-air" version.

A combination of these head positions is common; many patients experience turning and tilting actions of the head.[10]

Treatment

[edit]There are several treatments for spasmodic torticollis, the most commonly used being botulinum toxin injections in the dystonic muscle of the neck. Other treatments include sensory trick for a mild occasional twinge, oral medications, and deep brain stimulation. Combinations of these treatments have been used to control spasmodic torticollis.[7] In addition, selective surgical denervation of nerves triggering muscle contractions may offer relief from spasms and pain, and limit damage to the spine as a result of torqued posture. Spinal fibrosis (i.e., locking of spinal facets due to muscular contortion resulting in fused vertebrae) may occur rapidly.

This suggests that the desynchronization of the frequency range is movement related.[5] Obtaining relief via a "sensory trick", also known as a geste antagoniste, is a common characteristic present in focal dystonias, most prevalently in cervical dystonia; however, it has also been seen in patients with blepharospasm.[11] Sensory tricks offer only temporary and often partial relief of spasmodic torticollis. 74% of patients report only partial relief of spasmodic torticollis compared to 26% reporting complete relief. The sensory trick must also be applied by the patient themselves. When the sensory trick is applied by an examiner, only 32% of patients report relief comparable to relief during self-application.[7] Since the root of the problem is neurological, doctors have explored sensorimotor retraining activities to enable the brain to "rewire" itself and eliminate dystonic movements.[12][13][14][15]

Oral medications

[edit]In the past, dopamine blocking agents have been used in the treatment of spasmodic torticollis. Treatment was based on the theory that there is an imbalance of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the basal ganglia. These drugs have fallen out of fashion due to various serious side effects: sedation, parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia.[16] Other oral medications can be used in low doses to treat early stages of spasmodic torticollis. Relief from spasmodic torticollis is higher in those patients who take anticholinergic agents when compared to other oral medications. Many have reported complete management with gabapentin alone or in combination with another drug such as clonazepam.[citation needed] 50% of patients who use anticholinergic agents report relief, 21% of patients report relief from clonazepam, 11% of patients report relief from baclofen, and 13% from other benzodiazepines.[17]

Higher doses of these medications can be used for later stages of spasmodic torticollis; however, the frequency and severity of side effects associated with the medications are usually not tolerated. Side effects include dry mouth, cognitive disturbance, drowsiness, diplopia, glaucoma and urinary retention.[18]

Botulinum toxin

[edit]

The most commonly used treatment for spasmodic torticollis is the use of botulinum toxin injection in the dystonic musculature. Botulinum toxin type A is most often used; it prevents the release of acetylcholine from the presynaptic axon of the motor end plate, paralyzing the dystonic muscle.[16] By disabling the movement of the antagonist muscle, the agonist muscle is allowed to move freely. With botulinum toxin injections, patients experience relief from spasmodic torticollis for approximately 12 to 16 weeks.[19] There are several type A preparations available worldwide and in the United States.[20]

Some patients experience or develop immunoresistance to botulinum toxin type A and must use botulinum toxin type B. Approximately 4% to 17% of patients develop botulinum toxin type A antibodies. The only botulinum toxin type B accessible in the United States is Myobloc. Treatment using botulinum toxin type B is comparable to type A, with an increased frequency of the side effect dry mouth.[10][21]

Common side effects include pain at the injection site (up to 28%), dysphagia due to the spread to adjacent muscles (11% to 40%), dry mouth (up to 33%), fatigue (up to 17%), and weakness of the injected or adjacent muscle (up to 56%).[16] A Cochrane review published in 2016 reported moderate-quality evidence that a single Botulinum toxin-B treatment session could improve cervical dystonia symptoms by 10% to 20%, although with an increased risk of dry mouth and swallowing difficulties.[22] Another Cochrane review published in 2020 for Botulinum toxin-A found similar results.[23]

Deep brain stimulation

[edit]

Deep brain stimulation to the basal ganglia and thalamus has recently been used as a successful treatment for tremors of patients with Parkinson's disease. This technique is currently, as of 2007, being trialed in patients with spasmodic torticollis. Patients are subjected to stimulation of the globus pallidus internus, or the subthalamic nucleus. The device is analogous to a pacemaker: an external battery is placed subcutaneously, with wires under the skin which enter the skull and a region of the brain. To stimulate the globus pallidus internus, microelectrodes are placed into the globus pallidus internus bilaterally. After the surgery is performed, multiple visits are required to program the settings for the stimulator. The stimulation of the globus pallidus internus disrupts the abnormal discharge pattern in the globus pallidus internus, resulting in inhibition of hyperactive cortical activity. Globus pallidus internus deep brain stimulation is the preferred surgical procedure, due to the lower frequency of side effects.[16] Advantages of deep brain stimulation include the reversibility of the procedure, and the ability to adjust the settings of the stimulation.[17]

In one study, patients who had developed immunoresistance to botulinum toxin underwent globus pallidus internus deep brain stimulation, showing improvement by 54.4% after three to six months.[citation needed]

There is a low rate of side effects for those who undergo deep brain stimulation. The most common side effect is headache, occurring in 15% of patients, followed by infection (4.4%) and cognitive dysfunction (4%). Serious side effects are seizure (1.2%), intracerebral hemorrhage (0.6%), intraventricular hemorrhage (0.6%), and large subdural hematoma (0.3%).[16]

Physical Interventions

[edit]Physical treatment options for cervical dystonia include biofeedback, mechanical braces as well as patients self-performing a geste antagoniste. Physical therapy also has an important role in managing spasmodic torticollis by providing stretching and strengthening exercises to aid the patient in keeping their head in proper alignment with their body.[19] Patients with cervical dystonia ranked physical therapy intervention second to botulinum toxin injections in overall effectiveness in reducing symptoms[24] and patients receiving physiotherapy in conjunction with botulinum toxin injections reported enhanced effects of treatment compared to the injections alone.[25] One study examined patients with cervical dystonia who were treated with a physiotherapy program that included muscle stretching and relaxation, balance and coordination training, and exercises for muscle strengthening and endurance. A significant reduction in pain and severity of dystonia as well as increased postural awareness and quality of life was found.[26]

Epidemiology

[edit]Spasmodic torticollis is one of the most common forms of dystonia seen in neurology clinics, occurring in approximately 0.390% of the United States population in 2007 (390 per 100,000).[3] Worldwide, it has been reported that the incidence rate of spasmodic torticollis is at least 1.2 per 100,000 person years,[27] and a prevalence rate of 57 per 1 million.[28] The exact prevalence of the disorder is not known; several family and population studies show that as many as 25% of cervical dystonia patients have relatives that are undiagnosed.[29][30] Studies have shown that spasmodic torticollis is not diagnosed immediately; many patients are diagnosed well after a year of seeking medical attention.[1] A survey of 59 patients diagnosed with spasmodic torticollis show that 43% of the patients visited at least four physicians before the diagnosis was made.[31]

There is a higher prevalence of spasmodic torticollis in females; females are 1.5 times more likely to develop spasmodic torticollis than males. The prevalence rate of spasmodic torticollis also increases with age, most patients show symptoms from ages 50–69. The average onset age of spasmodic torticollis is 41.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Geyer HL; Bressman SB. (2006). "The diagnosis of dystonia". The Lancet Neurology. 5 (9): 780–790. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70547-6. PMID 16914406. S2CID 28374695.

- ^ "Spasmodic Torticollis – Signs and Symptoms". NSTA. National Spasmodic Torticollis Association. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Jankovic J; Tsui J; Bergeron C. (2007). "Prevalence of Cervical Dystonia and Spasmodic Torticollis in the United States general population". Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 13 (7): 411–6. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.02.005. PMID 17442609.

- ^ Vacherot F, Vaugoyeau M, Mallau S, Soulayrol S, Assaiante C, Azulay JP (May 2007). "Postural control and sensory integration in cervical dystonia". Clin Neurophysiol. 118 (5): 1019–27. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2007.01.013. PMID 17383228. S2CID 45602523.

- ^ a b Uc EY; Rodnitzky RL. (2003). "Childhood Dystonia". Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 10 (1): 52–61. doi:10.1016/S1071-9091(02)00010-4. PMID 12785748.

- ^ a b de Carvalho Aguiar PM, Ozelius LJ (September 2002). "Classification and genetics of dystonia". Lancet Neurol. 1 (5): 316–25. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(02)00137-0. PMID 12849429. S2CID 29200547.

- ^ a b c Tang JK, et al. (2007). "Changes in cortical and pallidal oscillatory activity during the execution of a sensory trick in patients with cervical dystonia". Experimental Neurology. 204 (2): 845–8. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.01.010. hdl:1807/17904. PMID 17307166. S2CID 3255050.

- ^ Salvia P, Champagne O, Feipel V, Rooze M, de Beyl DZ (May 2006). "Clinical and goniometric evaluation of patients with spasmodic torticollis". Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 21 (4): 323–9. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.11.011. PMID 16427167.

- ^ Richter A, Löscher W (April 1998). "Pathology of idiopathic dystonia: findings from genetic animal models". Prog. Neurobiol. 54 (6): 633–77. doi:10.1016/S0301-0082(97)00089-0. PMID 9560845. S2CID 53173608.

- ^ a b Brashear A. (2004). "Treatment of cervical dystonia with botulinum toxin". Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 15 (2): 122–7. doi:10.1016/j.otot.2004.03.004.

- ^ Poisson, A.; Krack P.; Thobois S.; Loiraud C.; Serra G.; Vial C.; Broussolle E. (2012). "History of the "geste antagoniste" sign in cervical dystonia". Journal of Neurology. 259 (8): 1580–1584. doi:10.1007/s00415-011-6380-7. PMID 22234840. S2CID 27142003.

- ^ "Dystonia. Rewiring the brain through movement and dance | Federico Bitti | TEDxNapoli". 13 July 2015 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "How your movements can heal your brain | Joaquin Farias | TEDxNapoli". 13 July 2015 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Farias J. Limitless. How your movements can heal your brain. An essay on the neurodynamics of dystonia. Galene editions 2016

- ^ Farias J. Intertwined. How to induce neuroplasticity. A new approach to rehabilitate dystonias. Galene editions 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Adam OR, Jankovic J (2007). "Treatment of dystonia". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 13 (Suppl 3): S362–8. doi:10.1016/S1353-8020(08)70031-2. PMID 18267265.

- ^ a b Crowner BE. (2007). "dystonia: disease profile and clinical management". Physical Therapy. 87 (11): 1511–26. doi:10.2522/ptj.20060272. PMID 17878433.

- ^ Ochudlo S; Drzyzga K; Drzyzga LR; Opala G. (2007). "Various patterns of gestes antagonists in cervical dystonia". Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 13 (7): 417–420. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.01.004. PMID 17355914.

- ^ a b Velickovic M, Benabou R, Brin MF (2001). "Cervical dystonia pathophysiology and treatment options". Drugs. 61 (13): 1921–43. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161130-00004. PMID 11708764. S2CID 46954613.

- ^ "Botulinum Neurotoxin Injections". Dystonia Medical Research Foundation. 2022-09-28. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ Walker, Thomas J.; Dayan, Steven H. (2014-02-01). "Comparison and Overview of Currently Available Neurotoxins". The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. 7 (2): 31–39. ISSN 1941-2789. PMC 3935649. PMID 24587850.

- ^ Marques, RE; Duarte, GS; Rodrigues, FB; Castelão, M; Ferreira, J; Sampaio, C; Moore, AP; Costa, J (13 May 2016). "Botulinum toxin type B for cervical dystonia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (5): CD004315. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004315.pub3. PMC 8552447. PMID 27176573.

- ^ Rodrigues, Filipe B.; Duarte, Gonçalo S.; Marques, Raquel E.; Castelão, Mafalda; Ferreira, Joaquim; Sampaio, Cristina; Moore, Austen P.; Costa, João (November 12, 2020). "Botulinum toxin type A therapy for cervical dystonia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (11): CD003633. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003633.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8106615. PMID 33180963.

- ^ Silfors, Anders; Göran Solders (2002). "Living with dystonia. A questionnaire among members of the Swedish Dystonia Patient Association". Läkartidningen. 99 (8): 786–789.

- ^ Tassorelli C, Mancini F, Balloni L, Pacchetti C, Sandrini G, Nappi G, Martignoni E (December 2006). "Botulinum toxin and neuromotor rehabilitation: An integrated approach to idiopathic cervical dystonia". Mov. Disord. 21 (12): 2240–3. doi:10.1002/mds.21145. PMID 17029278. S2CID 16366190.

- ^ Zetterberg L, Halvorsen K, Färnstrand C, Aquilonius SM, Lindmark B (2008). "Physiotherapy in cervical dystonia: six experimental single-case studies". Physiother Theory Pract. 24 (4): 275–90. doi:10.1080/09593980701884816. PMID 18574753. S2CID 20722262.

- ^ Claypool DW, Duane DD, Ilstrup DM, Melton LJ (September 1995). "Epidemiology and outcome of cervical dystonia (spasmodic torticollis) in Rochester, Minnesota". Mov. Disord. 10 (5): 608–14. doi:10.1002/mds.870100513. PMID 8552113. S2CID 25177370.

- ^ The Epidemiological Study of Dystonia in Europe (ESDE) Collaborative (2000). "A prevalence study of primary dystonia in eight European countries". Journal of Neurology. 247 (10): 787–92. doi:10.1007/s004150070094. PMID 11127535. S2CID 26041305.

- ^ Waddy HM, Fletcher NA, Harding AE, Marsden CD (March 1991). "A genetic study of idiopathic focal dystonias". Ann. Neurol. 29 (3): 320–4. doi:10.1002/ana.410290315. PMID 2042948. S2CID 37961232.

- ^ Duffey PO, Butler AG, Hawthorne MR, Barnes MP (1998). "The epidemiology of the primary dystonias in the north of England". Adv Neurol. 78: 121–5. PMID 9750909.

- ^ van Herwaarden GM, Anten HW, Hoogduin CA, et al. (August 1994). "Idiopathic spasmodic torticollis: a survey of the clinical syndromes and patients' experiences". Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 96 (3): 222–5. doi:10.1016/0303-8467(94)90072-8. PMID 7988090. S2CID 27554275.