Torosaurus: Difference between revisions

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

Paleontologists investigating dinosaur [[ontogeny]] (growth and development of individuals over the life span) in the [[Hell Creek Formation]] of [[Montana]], have hypothesized that ''Triceratops'' and ''Torosaurus'' may be growth stages in a single genus.<ref name=scannella&horner2010>Scannella, J. and Horner, J.R. (2010). "Torosaurus Marsh, 1891, is Triceratops Marsh, 1889 (Ceratopsidae: Chasmosaurinae): synonymy through ontogeny ." ''Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology'', '''30'''(4): 1157 - 1168. {{doi|10.1080/02724634.2010.483632}}</ref> John Scannella, in a paper presented in [[Bristol]], [[UK]] at the conference of the [[Society of Vertebrate Paleontology]] (2009 September 25) reclassified the mature ''Torosaurus'' specimens as fully mature individuals of ''Triceratops''. [[Jack Horner (paleontologist)|Jack Horner]], Scannella's mentor at [[Montana State University System|Montana State University]], noted that ceratopsian skulls consist of [[metaplastic bone]]. A characteristic of metaplastic bone is that it lengthens and shortens over time, extending and resorbing to form new shapes. Significant variety is seen even in those skulls already identified as ''Triceratops'', Horner observed, "where the horn orientation is backwards in juveniles and forward in adults". Approximately 50% of all subadult ''Triceratops'' skulls have two thin areas in the frill that correspond with the placement of "holes" in ''Torosaurus'' skulls, suggesting that holes developed to offset the weight that would otherwise have been added as maturing ''Triceratops'' individuals grew longer frills.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/10/091031002314.htm |title=New Analyses Of Dinosaur Growth May Wipe Out One-third Of Species |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2009-10-31 |accessdate=2010-08-03}}</ref><ref>{{cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0007626}}</ref> In 2010 Scannella and Horner published their findings after examining the growth patterns in 38 skull specimens (29 of ''Triceratops'', 9 of ''Torosaurus'') from the Hell Creek formation. They concluded that ''Torosaurus'' actually represents the mature form of ''Triceratops''.<ref name=scannella&horner2010/> |

Paleontologists investigating dinosaur [[ontogeny]] (growth and development of individuals over the life span) in the [[Hell Creek Formation]] of [[Montana]], have hypothesized that ''Triceratops'' and ''Torosaurus'' may be growth stages in a single genus.<ref name=scannella&horner2010>Scannella, J. and Horner, J.R. (2010). "Torosaurus Marsh, 1891, is Triceratops Marsh, 1889 (Ceratopsidae: Chasmosaurinae): synonymy through ontogeny ." ''Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology'', '''30'''(4): 1157 - 1168. {{doi|10.1080/02724634.2010.483632}}</ref> John Scannella, in a paper presented in [[Bristol]], [[UK]] at the conference of the [[Society of Vertebrate Paleontology]] (2009 September 25) reclassified the mature ''Torosaurus'' specimens as fully mature individuals of ''Triceratops''. [[Jack Horner (paleontologist)|Jack Horner]], Scannella's mentor at [[Montana State University System|Montana State University]], noted that ceratopsian skulls consist of [[metaplastic bone]]. A characteristic of metaplastic bone is that it lengthens and shortens over time, extending and resorbing to form new shapes. Significant variety is seen even in those skulls already identified as ''Triceratops'', Horner observed, "where the horn orientation is backwards in juveniles and forward in adults". Approximately 50% of all subadult ''Triceratops'' skulls have two thin areas in the frill that correspond with the placement of "holes" in ''Torosaurus'' skulls, suggesting that holes developed to offset the weight that would otherwise have been added as maturing ''Triceratops'' individuals grew longer frills.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/10/091031002314.htm |title=New Analyses Of Dinosaur Growth May Wipe Out One-third Of Species |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2009-10-31 |accessdate=2010-08-03}}</ref><ref>{{cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0007626}}</ref> In 2010 Scannella and Horner published their findings after examining the growth patterns in 38 skull specimens (29 of ''Triceratops'', 9 of ''Torosaurus'') from the Hell Creek formation. They concluded that ''Torosaurus'' actually represents the mature form of ''Triceratops''.<ref name=scannella&horner2010/> |

||

This conclusion was challenged in 2011 by ceratopsian specialist Andrew Farke. He published a redescription of ''[[Nedoceratops|Nedoceratops hatcheri]]'', a problematic species that at various times has been considered a representative of its own genus, a synonym of a species of ''Triceratops'', a distinct species of ''Triceratops'', or, under the Scannella–Horner hypothesis, an example of an intermediate growth stage between ''Triceratops'' and ''Torosaurus''. Farke concluded that ''Nedoceratops hatcheri'' is an aged individual of its own genus, closely related to ''Triceratops''. He also regarded the changes required to "age" a ''Triceratops'' into a ''Torosaurus'' to be without precedent among ceratopsids, requiring addition of [[epoccipital]]s, reversion of bone texture from adult to immature back to adult, and late growth of holes in the frill.<ref name=AF2011>Farke, A. A. (2011) "[http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0016196 Anatomy and taxonomic status of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid ''Nedoceratops hatcheri'' from the Upper Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming, U.S.A..]" ''PLoS ONE'' '''6''' (1): e16196. {{doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0016196}}</ref> |

This conclusion was challenged in 2011 by ceratopsian specialist Andrew Farke. He published a redescription of ''[[Nedoceratops|Nedoceratops hatcheri]]'', a problematic species that at various times has been considered a representative of its own genus, a synonym of a species of ''Triceratops'', a distinct species of ''Triceratops'', or, under the Scannella–Horner hypothesis, an example of an intermediate growth stage between ''Triceratops'' and ''Torosaurus''. Farke concluded that ''Nedoceratops hatcheri'' is an aged individual of its own genus, closely related to ''Triceratops''. He also regarded the changes required to "age" a ''Triceratops'' into a ''Torosaurus'' to be without precedent among ceratopsids, requiring addition of [[epoccipital]]s, reversion of bone texture from adult to immature back to adult, and late growth of holes in the frill.<ref name=AF2011>Farke, A. A. (2011) "[http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0016196 Anatomy and taxonomic status of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid ''Nedoceratops hatcheri'' from the Upper Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming, U.S.A..]" ''PLoS ONE'' '''6''' (1): e16196. {{doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0016196}}</ref> However, Triceratops was larger than Torosaurus, so it's very debatable. |

||

==Paleobiology== |

==Paleobiology== |

||

Revision as of 04:20, 1 December 2011

| Torosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

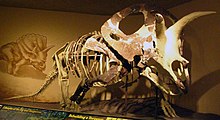

| Mounted skeleton, Milwaukee | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ceratopsia |

| Family: | †Ceratopsidae |

| Subfamily: | †Chasmosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Triceratopsini |

| Genus: | †Torosaurus Marsh, 1891 |

| Species | |

| |

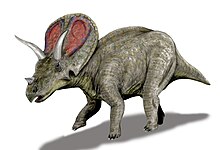

Torosaurus (meaning "perforated lizard", referring to the large openings in the frill; commonly mistranslated as "bull lizard") is a genus of ceratopsid dinosaur that lived during the late Cretaceous period (late Maastrichtian stage), between 70 and 65 million years ago. It possessed one of the largest skulls of any known land animal. The frilled skull reached 2.6 metres (8.5 ft) in length. From head to tail, Torosaurus is thought to have measured about 9 m (30 ft) long[1] and weighed 4 to 6 tonnes (4.4 to 6.6 tons).

In 2010, research on dinosaur ontogeny (growth and development of individuals over the life span) concluded that Torosaurus may not represent a distinct genus at all, but a mature form of Triceratops.[2][3]

Discoveries and species

In 1891, two years after the naming of Triceratops, a pair of ceratopsian skulls with elongated frills bearing holes were found in southeastern Wyoming by John Bell Hatcher. Paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh coined the genus Torosaurus for them. Similar specimens have since been found in Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, North Dakota, Utah and Saskatchewan. Fragmentary remains that could possibly be identified with the genus have been found in the Big Bend Region of Texas and in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico. Paleontologists have observed that Torosaurus specimens are relatively uncommon in the fossil record; specimens of Triceratops are more abundant.

Although the meaning of the name Torosaurus is frequently given as "bull lizard" (from the Latin taurus "bull"), the name probably means "perforated lizard" (from the Greek word toreo "pierce, perforate").[4] The allusion is to the window-like holes, or fenestrae, in the elongated frill, which have traditionally served to distinguish it from the solid frill of Triceratops. Much of the confusion over etymology of the name results from the fact that Marsh never explicitly explained it in his papers.

Two Torosaurus species have been identified:

- T. latus Marsh, 1891 (type species)

- T. utahensis Gilmore, 1946

Another identification was subsequently regarded as a misassignment:

- T. gladius Marsh, 1891 (=T. latus)

Torosaurus utahensis was originally described as Arrhinoceratops utahensis by Gilmore in 1946. Review by Sullivan et al. in 2005[5] left it as Torosaurus utahensis and somewhat older than T. latus. However, subsequent studies suggested it may well be either Arrhinoceratops or a new genus, as dinosaurs from the northern Hell Creek formation and southern "Alamosaurus fauna" rarely overlap and were probably separated by a geographic barrier. Research has not yet been published on whether T. utahensis should be regarded as a new genus or, as has been suggested for T. latus, the mature growth stage of a new species of Triceratops.[2]

No juvenile specimens of Torosaurus showing the identifying fenestrae have been found.[6]

Classification and debate

Torosaurus has traditionally been classified as part of the subfamily known as Chasmosaurinae, also known as Ceratopsinae, within the family Ceratopsidae, within the Ceratopsia (which name is Ancient Greek for "horned face"), a group of herbivorous dinosaurs with parrot-like beaks which thrived in North America and Asia during the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. Juvenile individuals have been excavated from a bonebed in the Javelina Formation of Big Bend National Park, identified as Torosaurus cf. utahensis based on their proximity to an adult with a characteristic Torosaurus parietal.[7] At least one study has indicated that Torosaurus was most closely related to Triceratops.[8]

Paleontologists investigating dinosaur ontogeny (growth and development of individuals over the life span) in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, have hypothesized that Triceratops and Torosaurus may be growth stages in a single genus.[2] John Scannella, in a paper presented in Bristol, UK at the conference of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (2009 September 25) reclassified the mature Torosaurus specimens as fully mature individuals of Triceratops. Jack Horner, Scannella's mentor at Montana State University, noted that ceratopsian skulls consist of metaplastic bone. A characteristic of metaplastic bone is that it lengthens and shortens over time, extending and resorbing to form new shapes. Significant variety is seen even in those skulls already identified as Triceratops, Horner observed, "where the horn orientation is backwards in juveniles and forward in adults". Approximately 50% of all subadult Triceratops skulls have two thin areas in the frill that correspond with the placement of "holes" in Torosaurus skulls, suggesting that holes developed to offset the weight that would otherwise have been added as maturing Triceratops individuals grew longer frills.[9][10] In 2010 Scannella and Horner published their findings after examining the growth patterns in 38 skull specimens (29 of Triceratops, 9 of Torosaurus) from the Hell Creek formation. They concluded that Torosaurus actually represents the mature form of Triceratops.[2]

This conclusion was challenged in 2011 by ceratopsian specialist Andrew Farke. He published a redescription of Nedoceratops hatcheri, a problematic species that at various times has been considered a representative of its own genus, a synonym of a species of Triceratops, a distinct species of Triceratops, or, under the Scannella–Horner hypothesis, an example of an intermediate growth stage between Triceratops and Torosaurus. Farke concluded that Nedoceratops hatcheri is an aged individual of its own genus, closely related to Triceratops. He also regarded the changes required to "age" a Triceratops into a Torosaurus to be without precedent among ceratopsids, requiring addition of epoccipitals, reversion of bone texture from adult to immature back to adult, and late growth of holes in the frill.[11] However, Triceratops was larger than Torosaurus, so it's very debatable.

Paleobiology

All ceratopsians, including Torosaurus and Triceratops, were herbivores. During the Cretaceous flowering plants were limited in their geographical distribution. It is likely that ceratopsians fed on the more abundant ferns, cycads and conifers, using their sharp beaks to bite off leaves or needles.

References

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2010 Appendix.

- ^ a b c d Scannella, J. and Horner, J.R. (2010). "Torosaurus Marsh, 1891, is Triceratops Marsh, 1889 (Ceratopsidae: Chasmosaurinae): synonymy through ontogeny ." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 30(4): 1157 - 1168. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.483632

- ^ Switek, Brian. "New Study Says Torosaurus=Triceratops". Dinosaur Tracking. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Dodson, P. (1996). The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, pp. xiv-346

- ^ Sullivan, R. M., A. C. Boere, and S. G. Lucas. 2005. Redescription of the ceratopsid dinosaur Torosaurus utahensis (Gilmore, 1946) and a revision of the genus. Journal of Paleontology 79:564-582.

- ^ "Morph-osaurs: How shape-shifting dinosaurs deceived us - life - 28 July 2010". New Scientist. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.483632. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ Hunt, ReBecca K. and Thomas M. Lehman. 2008. Attributes of the ceratopsian dinosaur Torosaurus, and new material from the Javelina Formation (Maastrichtian) of Texas. Journal of Paleontology 82(6): 1127-1138.

- ^ Farke, A. A. 2006. Cranial osteology and phylogenetic relationships of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Torosaurus latus; pp. 235-257 in K. Carpenter (ed.), Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

- ^ "New Analyses Of Dinosaur Growth May Wipe Out One-third Of Species". Sciencedaily.com. 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007626, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0007626instead. - ^ Farke, A. A. (2011) "Anatomy and taxonomic status of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Nedoceratops hatcheri from the Upper Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming, U.S.A.." PLoS ONE 6 (1): e16196. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016196

- Dodson, P. (1996). The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, pp. xiv-346

- Haines, Tim & Chambers, Paul. (2006)The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Canada: Firefly Books Ltd.

External links

- http://www.dinosaurvalley.com/Visiting_Drumheller/Kids_Zone/Groups_of_Dinosaurs/index.php

- http://www.dinosaurier-web.de/galery/pages_t/torosaurus.html

- http://www.newscientist.com/articleimages/mg20727713.500/1-morphosaurs-how-shapeshifting-dinosaurs-deceived-us.html Chart showing Triceratops/Torosaur growth and development (New Scientist)