Name of Ukraine

| History of Ukraine |

|---|

|

The earliest known usage of the name Ukraine (Ukrainian: Україна, romanized: Ukraina [ʊkrɐˈjinɐ] ⓘ, Вкраїна, romanized: Vkraina [u̯krɐˈjinɐ]; Old East Slavic: Ѹкраина/Ꙋкраина, romanized: Ukraina [uˈkrɑjinɑ]) appears in the Hypatian Codex of c. 1425 under the year 1187 in reference to a part of the territory of Kievan Rus'.[1][2] The use of "the Ukraine" has been officially deprecated by the Ukrainian government and many English-language media publications.[3][4][5]

Ukraine is the official full name of the country, as stated in its declaration of independence and its constitution; there is no official alternative long name. From 1922 until 1991, Ukraine was the informal name of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic within the Soviet Union (annexed by Germany as Reichskommissariat Ukraine during 1941–1944). After the Russian Revolution in 1917–1921, there were the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic and Ukrainian State, recognized in early 1918 as consisting of nine governorates of the former Russian Empire (without Taurida's Crimean Peninsula), plus Chelm and the southern part of Grodno Governorate.[6]

Etymology

[edit]Although the exact meaning of the word ukraïna or ukrajina as a whole is disputed, there is agreement that krajina is derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *krei, meaning "to cut", with "edge" as a secondary meaning.[7] The Proto-Slavic word *krajь generally meant "edge",[8] related to the verb *krojiti "to cut (out)",[9] in the sense of "division", either "at the edge, division line", or "a division, region".[10] In Old Church Slavonic, krai has been attested with the meanings of "edge, end, shore",[8] while Church Slavonic кроити (kroiti), краяти (krajati) could mean 'the land someone carved out for themselves' according to Hryhoriy Pivtorak (2001).[10] Derivatives in modern Slavic languages include variations of kraj or krai in a wide array of senses, such as "edge, country, land, end, region, bank, shore, side, rim, piece (of wood), area."[11]

Originally, the word ѹкра́ина (вкра́ина), from which the proper noun has been derived, formed in particular from the root -краи- (krai) and the prefix ѹ-/в-[a] that later merged with the root due to metanalysis.

The ambiguity occurs due to the polysemous nature of the root край, as it may mean either a boundary/edge of a certain area or an area defined by certain boundaries,[13][14][circular reference] nevertheless the both meanings allow for the formation of a valid toponym. For instance, the country name Danmark is a composition Danish + boundary.[15][16][circular reference]

History

[edit]Kievan Chronicle (Hypatian Codex) sub anno 1187 and 1189

[edit]The oldest recorded mention of the word ukraina is found in the Kievan Chronicle under the year 1187,[2] as preserved in the Hypatian Codex written c. 1425 in an Old East Slavic variety of Church Slavonic.[7] The passage narrates the death of Volodimer Glebovich, prince of Pereyaslavl'[7] (r. 1169–1187):[b]

in 1187 as оукраина ukraina (NOM)

in 1189 as оукраинѣ ukraině (DAT)

ѡ нем же Ѹкраина много постона.[1] (ō nem zhe Ukraina mnogo postona).

"The frontier (Ukraina) mourned a great deal for him." (Lisa L. Heinrich, 1977)[b]

"The ukraïna groaned with grief for him." (Paul R. Magocsi, 2010)[7]

In context, Ukraina referred to the territory of the Principality of Pereyaslavl,[b][2] which was located between Kievan Rus' heartland in the Middle Dnieper region to the west, and the Pontic–Caspian steppe to the southeast,[18] which the Rus' chronicles customarily referred to as "the land of the Polovtsi".[c] "Ukraine" came to mean "steppe frontier" or "steppe borderland" in the Ukrainian, Polish and Russian languages thereafter.[2]

The next mention of ukraina in the same Kievan Chronicle occurs sub anno 1189,[7] which narrates how a certain Rostislav Berladnichich was invited by some, but not all, "men of Galich" (modern Halych), to take power in the Principality of Galicia:[21]

еха и Смоленьска в борзѣ и приѣхавшю же емоу ко Оукраинѣ Галичькои и взя два города Галичькъıи и отолѣ поіде к Галичю.[1]

"And he went in haste from Smolensk, and when he had come to the Galičan frontier," (ukraině Galichĭkoi) "he captured two Galičan cities. And from there he went to [the city of] Galič (...)." (Lisa L. Heinrich, 1977)[21]

Serhii Plokhy (2015, 2021) connected the 1189 mention to that of 1187, stating that both referred to the same region: '1187–1189 A Kyivan chronicler first uses the word "Ukraine" to describe the steppe borderland from Pereiaslav in the east to Galicia in the west.'[22]

Late Middle Ages

[edit]The Kievan Chronicle and subsequent Galician–Volhynian Chronicle in the Hypatian Codex mention ukraina again under the years 1189, 1213, 1280, and in 1282, where it is applied in various contexts.[7] In these decades, and the following centuries until the end of the Middle Ages, this term was applied to fortified borderlands of different principalities of Rus' without a specific geographic fixation: Halych-Volhynia,[7][23] the (Western) Buh region,[7] Pskov,[7][23] Polatsk,[7] Ryazan etc.[23]: 183 [24] According to Serhii Plokhy (2006), 'the Muscovites referred to their steppe borderland as "Ukraine," while reserving different names for areas bordering on the settled territories of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland.'[2]

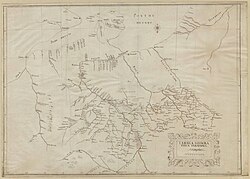

Early modern cartography

[edit]

The Radziwiłł map of 1613 (formal title Magni Ducatus Lithuaniae; originally published in 1603[25]) was the first map to indicate the terms "Ukraine" and "Cossacks".[26] In the mid-17th century, Franco-Polish cartographer Guillaume Le Vasseur de Beauplan, who had spent the 1630s as a military engineer and architect designing and building fortifications in the region, played a significant role in popularising Ukraine as a name and a concept to a broader Western European audience, both through his maps and his writings.[27] His 1648 map in Latin was titled Delineatio Generalis Camporum Desertorum vulgo Ukraina. Cum adjacentibus Provinciis ("General illustration of desert plains, in vernacular (speech) Ukraine. With adjacent Provinces."), thereby 'using the term "Ukraine" to denote all the provinces of the Kingdom of Poland that bordered on the uninhabited steppe areas (campus desertorum)'.[28][29] Beauplan's French-language publication of the second edition of Description d'Ukranie ("Description of Ukraine", the first edition dates from 1651[30]) defined Ukraine as "several provinces of the Kingdom of Poland lying between the borders of Muscovy and the frontiers of Transylvania".[28] This book became wildly popular in Western Europe, and was translated into Latin, Dutch, Spanish and English in the 1660s to 1680s, and reprinted numerous times throughout the rest of the 17th century and the entire 18th century.[28] On another map,[which?] published in Amsterdam in 1645, the sparsely inhabited region to the north of the Azov sea is called Okraina and is characterized to the proximity to the Dikoye pole (Wild Fields), posing a constant threat of raids of Turkic nomads (Crimean Tatars and the Nogai Horde).[citation needed]

-

Vkraina and Kyovia on the 1613 Radziwiłł map, with the "steppe fields" on "this" and "that" side of the "Boristenus now Niepr river"

-

1635 map by Beauplan called Tabula Geographica Ukrainska ("Ukrainian Geographical Table"). North is at the bottom.

-

1648 map by Beauplan called Delineatio Generalis Camporum Desertorum vulgo Ukraina ("General illustration of desert plains, in vernacular Ukraine")

-

1648 Beauplan map title: Ukrainæ pars, qvæ Kiovia palatinus Vulgo dicitur ("Part of Ukraine, called Voivodeship of Kiov in vernacular")

-

Map of Eastern Europe by Vincenzo Coronelli (1690). The lands around Kyiv are shown as V(U)kraine ou pays des Cosaques ("Ukraine or the land of Cossacks").

Early modern Slavonic texts

[edit]

By the 17th century, Ukraine was sometimes used to define various other, non-steppe borderlands, but the word received more commonly-used and eventually fixed meanings in the second half of the 17th century.[27] After the south-western lands of former Rus' were subordinated to the Polish Crown in 1569, the territory from eastern Podillia to Zaporizhia got the unofficial name Ukraina due to its border function to the nomadic Tatar world in the south.[32] A 1580 royal decree by Stefan Batory 'made mention of Ruthenian, Kyivan, Volhynian, Podolian, and Bratslavian Ukraine'.[2] The Polish chronicler Samuel Grądzki (died 1672), who wrote about the Khmelnytsky Uprising in 1660, explained the word Ukraina as the land located at the edge of the Polish kingdom.[d] Thus, in the course of the 16th–18th centuries Ukraine became a concrete regional name among other historic regions such as Podillia, Severia, or Volhynia. It was used for the middle Dnieper River territory controlled by the Cossacks.[23]: 184 [24] The people of Ukraina were called Ukrainians (українці, ukraintsi, or українники, ukrainnyky).[34]

Later, the term Ukraine was used for the Cossack Hetmanate lands on both sides of the Dnieper, although it didn't become the official name of the state.[24] Nevertheless, in diplomatic correspondence between the Zaporozhian Host and the tsar of Muscovy, Cossack officials increasingly used the term "Ukraine" to denote the Cossack Hetmanate ever since Bohdan Khmelnytsky's leadership.[35] A May 1660 set of negotiation instructions written by hetman Yurii Khmelnytsky defined "Ukraine" as the territory controlled by the Cossack state according to the Treaty of Zboriv (1649), thus making it a political rather than geographic term.[35] The scope of this Cossack political concept of Ukraine was remarkably different from that popularised by Beauplan (who was influenced by Polish traditions) around the same time; Beauplan's Vkrainie was first and foremost a set of voivodeships controlled by the Kingdom of Poland, characterised by their juxtaposition to the steppes as opposed to the rest of Poland.[35]

Modern period

[edit]From the 18th century on, Ukraine became known in the Russian Empire by the geographic term Little Russia.[23]: 183–184 In the 1830s, Mykola Kostomarov and his Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Kyiv started to use the name Ukrainians.[citation needed] It was also taken up by Volodymyr Antonovych and the Khlopomany ("peasant-lovers"), former Polish gentry in Eastern Ukraine, and later by the Ukrainophiles in Halychyna, including Ivan Franko. The evolution of the meaning became particularly obvious at the end of the 19th century.[23]: 186 The term is also mentioned by the Russian scientist and traveler of Ukrainian origin Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay (1846–1888). At the turn of the 20th century the term Ukraine became independent and self-sufficient, pushing aside regional self-definitions.[23]: 186 In the course of the political struggle between the Little Russian and the Ukrainian identities, it challenged the traditional term Little Russia (Russian: Малороссия, romanized: Malorossiia) and ultimately defeated it in the 1920s during the Bolshevik policy of Korenization and Ukrainization.[36][37][page needed]

Interpretation

[edit]Interpretation as "borderland"

[edit]

Since the first known usage in 1187, and almost until the 18th century, in written sources, this word was used in the meaning of "border lands", without reference to any particular region with clear borders, including far beyond the territory of modern Ukraine. The generally accepted and frequently used meaning of the word as "borderland" has increasingly been challenged by revision, motivated by self-asserting of identity.[38]

The etymology of the word Ukraine is seen this way in most etymological dictionaries,[citation needed] such as Max Vasmer's etymological dictionary of Russian;[39] Orest Subtelny,[40] Paul Magocsi,[41] Omeljan Pritsak,[42] Mykhailo Hrushevskyi,[43] Ivan Ohiyenko,[44] Petro Tolochko[45] and others. It is supported by Jaroslav Rudnyckyj in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine[46] and the Etymological dictionary of the Ukrainian language (based on that of Vasmer).[47]

Interpretation as "region, country"

[edit]Ukrainian scholars and specialists in Ukrainian and Slavic philology have interpreted the term ukraina in the sense of "region, principality, country",[48] "province", or "the land around" or "the land pertaining to" a given centre.[49][50]

Linguist Hryhoriy Pivtorak (2001) argues that there is a difference between the two terms україна (Ukraina, "territory") and окраїна (okraina, "borderland"). Both are derived from the root krai, meaning "border, edge, end, margin, region, side, rim" but with a difference in preposition, U (ѹ)) meaning "at" vs. o (о) meaning "about, around"; *ukrai and *ukraina would then mean "a separated land parcel, a separate part of a tribe's territory". Lands that became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Chernihiv Principality, Siversk Principality, Kyiv Principality, Pereyaslavl Principality and most of Volyn Principality) were sometimes called Lithuanian Ukraina, while lands that became part of Poland (Halych Principality and part of Volyn Principality) were called Polish Ukraina. Pivtorak argues that Ukraine had been used as a term for their own territory by the Ukrainian Cossacks of the Zaporozhian Sich since the 16th century, and that the conflation with okraina "borderlands" was a creation of tsarist Russia.[e] Russian scholars contest this.[citation needed]

Official names

[edit]Below are the names of the Ukrainian states throughout the 20th century:

- 1917–1920: Ukrainian People's Republic;[51] controlled most of Ukraine, with the exception of West Ukraine[citation needed]

- April–December 1918: Ukrainian State (Ukrainian: Українська Держава, romanized: Ukrainska Derzhava) or "Second Hetmanate",[52] after the Hetman Coup (Гетьманський переворот)[citation needed]

- 1918–1919: West Ukrainian People's Republic within West Ukraine; the Unification Act with UPR failed to be implemented[citation needed]

- 1919–1936: Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic (Ukrainian: Українська Соціялїстична Радянська Република, romanized: Ukrainska Sotsiyalïstychna Radianska Republyka[53])

- 1936–1941: Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic[51] (Ukrainian: Українська Радянська Соціалістична Республіка, romanized: Ukrainska Radianska Sotsialistychna Respublika[54])

- 1941–1944: There was no Ukrainian state under Nazi occupation (though one was declared); the territory was governed as Reichskommissariat Ukraine (RKU)[citation needed]

- 1941–1991: Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukrainian: Українська Радянська Соціалістична Республіка, romanized: Ukrainska Radianska Sotsialistychna Respublika[51])

- 1991–present: Ukraine (Ukrainian: Україна, romanized: Ukraina[51])

English definite article

[edit]Ukraine is one of a few English country names traditionally used with the definite article the.[3] Use of the article was standard before Ukrainian independence, but has decreased since the 1990s.[4][5][55] For example, the Associated Press dropped the article "the" on 3 December 1991.[5] Use of the definite article was criticised as suggesting a non-sovereign territory, much like "the Lebanon" referred to the region before its independence, or as one might refer to "the Midwest", a region of the United States.[56][57][58][f]

In 1993, the Ukrainian government explicitly requested that, in linguistic agreement with countries and not regions,[61] the Russian preposition в, v, be used instead of на, na,[62] and in 2012, the Ukrainian embassy in London further stated that it is politically and grammatically incorrect to use a definite article with Ukraine.[3] Use of Ukraine without the definite article has since become commonplace in journalism and diplomacy (examples are the style guides of The Guardian[63] and The Times[64]).

Preposition usage in Slavic

[edit]

In Slovak: na Ukrajine ("at Ukraine");

in Ukrainian: v Ukrayini ("in Ukraine").

In the Ukrainian language both v Ukraini (with the preposition v - "in") and na Ukraini (with the preposition na - "on") have been used, although the preposition v is used officially and is more frequent in everyday speech.[citation needed] Modern linguistic prescription in Russian dictates usage of na,[65] while earlier official Russian language have sometimes used 'v',[66] just like authors foundational to Russian national identity.[67] Similar to the definite article issue in English usage, use of na rather than v has been seen as suggesting non-sovereignty. While v expresses "in" with a connotation of "into, in the interior", na expresses "in" with the connotation of "on, onto" a boundary (Pivtorak cites v misti "in the city" vs. na seli "in the village", viewed as "outside the city"). Pivtorak notes that both Ukrainian literature and folk song uses both prepositions with the name Ukraina (na Ukraini and v Ukraini), but argues that only v Ukraini should be used to refer to the sovereign state established in 1991.[10] The insistence on v appears to be a modern sensibility,[according to whom?] as even authors foundational to Ukrainian national identity used both prepositions interchangeably, e.g. T. Shevchenko within the single poem V Kazemati (1847).[68][non-primary source needed]

The preposition na continues to be used with Ukraine in the West Slavic languages (Polish, Czech, Slovak), while the South Slavic languages (Bulgarian, Serbo-Croatian, Slovene) use v exclusively.[citation needed]

Phonetics and orthography

[edit]Among the western European languages, there is inter-language variation (and even sometimes intra-language variation) in the phonetic vowel quality of the ai of Ukraine, and its written expression.[citation needed] It is variously:

- Treated as a diphthong (for example, English Ukraine /juːˈkreɪn/)

- Treated as a pure vowel (for example, French Ukraine [ykʁɛn])

- Transformed in other ways (for example, Spanish Ucrania [uˈkɾanja], or Portuguese Ucrânia [uˈkɾɐnjɐ])

- Treated as two juxtaposed vowel sounds, with some phonetic degree of an approximant [j] between that may or may not be recognized phonemically: German Ukraine [ukʁaˈiːnə] (although the realisation with the diphthong [aɪ̯] is also possible: [uˈkʁaɪnə]). This pronunciation is represented orthographically with a diaeresis, or tréma, in Dutch Oekraïne [ukraːˈ(j)inə]. This version most closely resembles the vowel quality of the Ukrainian word.

In Ukrainian itself, there is a "euphony rule" sometimes used in poetry and music which changes the letter У (U) to В (V) at the beginning of a word when the preceding word ends with a vowel or a diphthong. When applied to the name Україна (Ukraina), this can produce the form Вкраїна (Vkraina), as in song lyric Най Вкраїна вся радіє (Nai Vkraina vsia radiie, "Let all Ukraine rejoice!").[69]

See also

[edit]- Etymology of Rus’ and derivatives

- List of etymologies of administrative divisions: "Ukraine"

- All-Russian nation

- Fuentes de Andalucía, which renamed itself to Ukraine in 2022

- Little Russia

- Kyiv

- Toponymy

Notes

[edit]- ^ The phenomenon of alternating ѹ (modern у) and в in prepositions and prefixes is inherent in the Ukrainian language, e.g. 'ѹ се лѣто'/'В лѣто ҂s҃ х к҃s' in Kyivan Chronicle.[12][circular reference]

- ^ a b c "On that journey Vladimir Glebovič fell ill with a grave illness, from which he (later) died. And they brought him on stretchers to his city, Perejaslavl', and there he died [on 18 April] (...) And all the people of Perejaslavl' wept for him (...). The frontier (Ukraina) mourned a great deal for him."[17]

- ^ For example, sub anno 1177[19] and 1190.[20]

- ^ Margo enim polonice kray; inde Ukrajna, quasi provincia ad fines regni posita.[33][better source needed]

- ^ Російські шовіністи стали пояснювати назву нашого краю Україна як «окраїна Росії», тобто вклали в це слово принизливий і невластивий йому зміст. З історією виникнення назви Україна тісно пов'язане правило вживання прийменників на і в при позначенні місця або простору. ("Russian chauvinists began to explain the name of our land Ukraine as "the outskirts [okraina] of Russia", that is, they put a derogatory and uncharacteristic meaning into this word. Closely related to the history of the name Ukraine is the rule of using the prepositions on and in to refer to a place or space.")[10]

- ^ In British English, usage of "the Lebanon" lingered for decades after 1945, for instance in the title of a 1984 single by the band The Human League, or in remarks by Prime Ministers such as Margaret Thatcher[59] and John Major.[60][original research?][non-primary source needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Въ лЂто 6694 [1186] – 6698 [1190]. Іпатіївський літопис" [In the year 6694 [1186] – 6698 [1190]. The Hypatian Codex]. litopys.org.ua (in Church Slavic). 1908. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Plokhy 2006, p. 317.

- ^ a b c "Ukraine or the Ukraine: Why do some country names have 'the'?". BBC News. 7 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Why Ukraine Isn't 'The Ukraine,' And Why That Matters Now". Business Insider. 9 December 2013.

- ^ a b c "The "the" is gone" (PDF). The Ukrainian Weekly. 8 December 1991. p. 5. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

As of December 3, the Associated Press changed its style, alerting its editors, reporters and all who use the news service to the fact that the name of the Ukrainian republic would henceforth be written as simply "Ukraine"

- ^ Magocsi, Paul R. (1985), Ukraine, a historical atlas, Matthews, Geoffrey J., University of Toronto Press, p. 21, ISBN 0-8020-3428-4, OCLC 13119858

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Magocsi 2010, p. 189.

- ^ a b Derksen 2008, p. 244.

- ^ Derksen 2008, pp. 244–245, 248.

- ^ a b c d Pivtorak 2001.

- ^ Derksen 2008, pp. 244–245.

- ^ "украина", Wiktionary, the free dictionary, 5 April 2023, retrieved 13 August 2023

- ^ "краи", Wiktionary, the free dictionary, 10 July 2023, retrieved 13 August 2023

- ^ "край", Wiktionary, the free dictionary, 9 August 2023, retrieved 13 August 2023

- ^ "Danmark", Wiktionary, the free dictionary, 18 March 2023, retrieved 13 August 2023

- ^ "Denmark", Wiktionary, the free dictionary, 4 August 2023, retrieved 13 August 2023

- ^ Heinrich 1977, p. 423.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Heinrich 1977, p. 368.

- ^ Heinrich 1977, p. 443.

- ^ a b Heinrich 1977, p. 437.

- ^ Plokhy 2021, p. 448.

- ^ a b c d e f g Пономарьов А. П. Етнічність та етнічна історія України: Курс лекцій.—К.: Либідь, 1996.— 272 с.: іл. І8ВМ 5-325-00615-0.

- ^ a b c Е. С. Острась. ЗВІДКИ ПІШЛА НАЗВА УКРАЇНА //ВІСНИК ДОНЕЦЬКОГО УНІВЕРСИТЕТУ, СЕР. Б: ГУМАНІТАРНІ НАУКИ, ВИП.1, 2008 Archived 2013-11-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Braziūnienė 2019, p. 63.

- ^ Plokhy, Serhii (2017). "Princes and Cossacks: Putting Ukraine on the Map of Europe" (PDF). In Flier, Michael S.; Kivelson, Valerie A.; Monahan, Erika; Rowland, Daniel (eds.). Seeing Muscovy Anew: Politics—Institutions—Culture. Essays in Honor of Nancy Shields Kollmann. Bloomington, IN: Slavica Publishers. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-89357-481-9.

- ^ a b Plokhy 2006, pp. 316–318.

- ^ a b c Plokhy 2006, p. 316.

- ^ "Delineatio generalis Camporum Desertorum vulgo Ukraina: Cum adjacentibus provinciis". Library of Congress.

- ^ Essar, Dennis F.; Pernal, Andrew B. (1990). "The First Edition (1651) of Beauplan's Description d'Ukranie". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 14 (1/2): 84–96. ISSN 0363-5570.

- ^ Plokhy 2006, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Украина // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона: В 86 томах (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

- ^ [1] Andrey Vladimirovich Storozhenko (1925).

- ^ Русина О. В. Україна під татарами і Литвою. — Київ: Видавничий дім «Альтернативи», 1998. — С. 278.

- ^ a b c Plokhy 2006, p. 318.

- ^ Миллер, Алексей Ильич (Miller, Aleksey Ilyich), Дуализм идентичностей на Украине Archived 2013-07-30 at the Wayback Machine // Отечественные записки. — № 34 (1) 2007. С. 84-96

- ^ Martin T. The Affirmative Action Empire. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2001

- ^ Larissa M. L. Zaleska Onyshkevych, Maria G. Rewakowicz (2014). Contemporary Ukraine on the Cultural Map of Europe. Routledge. p. 365. ISBN 9781317473787.

- ^ "Invalid query". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ Orest Subtelny. Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press, 1988

- ^ A History of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press, 1996 ISBN 0-8020-0830-5

- ^ From Kyïvan Rus' to modern Ukraine: Formation of the Ukrainian nation (with Mykhailo Hrushevski and John Stephen Reshetar). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Ukrainian Studies Fund, Harvard University, 1984.

- ^ Грушевський М. Історія України-Руси. Том II. Розділ V. Стор. 4

- ^ "II. НАШІ НАЗВИ: РУСЬ — УКРАЇНА — МАЛОРОСІЯ. Іван Огієнко. Історія української літературної мови". litopys.org.ua.

- ^ Толочко П. П. «От Руси к Украине» («Від Русі до України». 1997

- ^ "Україна. Русь. Назви території і народу". litopys.org.ua.

- ^ Етимологічний словник української мови: У 7 т. / Редкол. О. С. Мельничук (голов. ред.) та ін. — К.: Наук. думка, 1983 — Т. 6: У — Я / Уклад.: Г. П. Півторак та ін. — 2012. — 568 с. ISBN 978-966-00-0197-8.

- ^ Шелухін, С. Україна — назва нашої землі з найдавніших часів. Прага, 1936. Андрусяк, М. Назва «Україна»: «країна» чи «окраїна». Прага, 1941; Історія козаччини, кн. 1—3. Мюнхен. Ф. Шевченко: термін "Україна", "Вкраїна" має передусім значення "край", "країна", а не "окраїна": том 1, с. 189 в Історія Української РСР: У 8 т., 10 кн. — К., 1979.

- ^ Shkandrij, Myroslav (2001). Russia and Ukraine: literature and the discourse of empire from Napoleonic to postcolonial times. Montreal, Que.: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7735-6949-2. OCLC 180773067.

- ^ Knysh, George (1991). Rus and Ukraine in Mediaeval Times. Winnipeg: Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in Canada. pp. 26–27, 38 (note 88).

- ^ a b c d Encarta 2002.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 520.

- ^ 1921 Constitution of Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic.

- ^ 1937 Constitution (Basic Law) of Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

- ^ "Ukraine". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "'Ukraine' or 'the Ukraine'? It's more controversial than you think". Washington Post. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ Trump discusses Ukraine and Syria with European politicians via video link, The Guardian (11 September 2015)

- ^ Let's Call Ukraine By Its Proper Name, Forbes (17 February 2016)

- ^ "House of Commons PQs". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ "Mr Major's Commons Statement on the Gulf War – 17 January 1991". John Major Archive. 17 January 1991. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ "The Nerd's Guide to Russian Prepositions In and On". Moscow. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Граудина, Л. К.; Ицкович, В. А.; Катлинская, Л. П (2001). Грамматическая правильность русской речи [Grammatically Correct Russian Speech] (in Russian). Москва. p. 69.

В 1993 году по требованию Правительства Украины нормативными следовало признать варианты в Украину (и соответственно из Украины). Тем самым, по мнению Правительства Украины, разрывалась не устраивающая его этимологическая связь конструкций на Украину и на окраину. Украина как бы получала лингвистическое подтверждение своего статуса суверенного государства, поскольку названия государств, а не регионов оформляются в русской традиции с помощью предлогов в (во) и из...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The Guardian Style Guide: Section 'U'". London. 19 December 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ "The Times: Online Style Guide - U". The Times. London. 16 December 2005. Archived from the original on 11 April 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "Горячие вопросы". Gramota.ru. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Указ о назначении Черномырдина послом в Украину". Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Незапно Карл поворотил / И перенес войну в Украйну.([2])

- ^ Мені однаково, чи буду / Я жить в Україні, чи ні. / [...] / На нашій славній Україні, / На нашій – не своїй землі ("It is the same to me, if I will / live in [v] Ukraine or not. / [...] / In [na] our glorious Ukraine / in [na] our, not their land") ([poetyka.uazone.nethttp://poetyka.uazone.net/kobzar/meni_odnakovo.html poetyka.uazone.net])

- ^ See for example, Rudnyc'kyj, J. B., Матеріали до українсько -канадійської фольклористики й діялектології / Ukrainian-Canadian Folklore and Dialectological Texts, Winnipeg, 1956

Bibliography

[edit]- Andrusjak, M. (1951). Nazva Ukrajina. Chicago.

- Balušok, Vasyl’ (2005). "Jak rusyny staly ukrajincjamy (How Rusyns became Ukrainians)". Dzerkalo Tyžnja (in Ukrainian). 27. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008.

- Borschak, E. (1984). "Rus, Mala Rossia, Ukraina". Revue des Études Slaves. 24.

- Derksen, Rick (2008). Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon. Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series. Leiden; Boston: Brill. p. 737. ISBN 978-90-04-15504-6. OCLC 179104910. Alt URL

- Dorošenko, D. (1931). "Die Namen 'Rus', 'Russland' und 'Ukraine' in ihrer historischen und gegenwärtigen Bedeutung". Abhandlungen des Ukrainischen Wissenschaftlichen Institutes (Berlin) (in German). doi:10.1515/9783112676721-001.

- "Oekraïne; Pools-Russische Oorlog". Encarta Encyclopedie Winkler Prins (in Dutch). Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum. 2002.

- Gregorovich, Andrew (1994). "Ukraine or 'the Ukraine'?". Forum Ukrainian Review. 90 (Spring/Summer).

- Heinrich, Lisa Lynn (1977). The Kievan Chronicle: A Translation and Commentary (PhD diss.). Nashville, Tennessee: Vanderbilt University. ProQuest 7812419

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). "The name 'Ukraine'". A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 171–72. ISBN 0-8020-7820-6.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 896. ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia: 980–1584. Second Edition. E-book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-36800-4.

- Ohijenko, Ivan (2001) [1949]. "Naši nazvy: Rus' – Ukrajina – Malorosija (Our names: Rus' – Ukraine – Little Russia)". Istorija ukrajins'koji literaturnoji movy (History of the Ukrainian standard language) (in Ukrainian). Kyiv: Naša kul’tura i nauka. pp. 98–105. ISBN 966-7821-01-3.

- Pivtorak, Hryhoriy Petrovych (2001). Походження українців, росіян, білорусів та їхніх мов Pochodžennja ukrajinciv, rosijan, bilorusiv ta jichnich mov [The Origin of Ukrainians, Belarusians, Russians and their languages] (in Ukrainian). Kyiv: Akademia. ISBN 966-580-082-5.

- Plokhy, Serhii (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (PDF). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–15. ISBN 978-0-521-86403-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Plokhy, Serhii (2021) [2015]. The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. Revised Edition. Basic Books. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-465-09346-5. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- Rudnyc’kyj, Jaroslav B.; Volodymyr Sichynskyi (1949). "Nazva Ukraïna (The name Ukraine)". Ent͡syklopedii͡a ukraïnoznavstva (Encyclopedia of Ukrainian studies). Vol. 1. Munich/New York. pp. 12–16.

- Rudnyt͡s′kyĭ, I͡a. B. (1951), Slovo ĭ nazva 'Ukraïna' in Onomastica, v 1, Winnipeg: UVAN.

- Šerech [= Shevelov], Yury (1952). "An important work in Ukrainian onomastics". Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S. 2 (4).

- Sičyns’kyj, V. (1944–1948). Nazva Ukrajiny. Terytorija Ukrajiny (The name of Ukraine. The territory of Ukraine). Prague/Augsburg.

- Skljarenko, Vitalij (1991). "Zvidky pochodyt' nazva Ukrajina? (What is the origin of the name Ukraine?)". Ukrajina (in Ukrainian). 1.

- Vasmer, Max (1953–58). Russisches etymologisches Wörterbuch (in German). Vol. 1–3. Heidelberg: Winter. Russian translation: Fasmer, Maks (1964–73). Ėtimologičeskij slovar' russkogo jazyka. Vol. 1–4. transl. Oleg N. Trubačev. Moscow: Progress.

- Braziūnienė, Alma (2019). "LDK 1613 m. žemėlapio laidos: istoriografinis aspektas". Knygotyra. 72: 62–89. doi:10.15388/Knygotyra.2019.72.21. ISSN 0204-2061. S2CID 199242255.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of Ukraine at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Ukraine at Wiktionary