Tom Holland (author)

Tom Holland | |

|---|---|

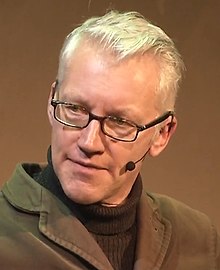

Holland in February 2020 | |

| Born | Thomas Holland 5 January 1968 Oxford, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | English |

| Alma mater | Queens' College, Cambridge University of Oxford |

| Genre | Literary fiction, non-fiction, history |

| Notable works | Rubicon (2003) Persian Fire (2005) In the Shadow of the Sword (2012) Dominion (2019) |

| Spouse |

Sadie Lowry (m. 1993) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | James Holland (brother) Charles Holland (great-uncle) |

| Website | |

| www | |

Thomas Holland FRSL (born 5 January 1968) is an English author and popular historian who has published best-selling books on topics including classical and medieval history, and the origins of Islam.

He has worked with the BBC to create and host historical television documentaries, and presented the radio series Making History. He co-hosts The Rest is History podcast with Dominic Sandbrook.

Early life and education

[edit]Holland was born in Oxfordshire and brought up in the village of Broad Chalke near Salisbury, Wiltshire, England,[1] the elder of two sons. His younger brother James Holland is also an author whose focus is World War II.[2] He has said that his two passions as a child were dinosaurs and ancient civilisations: "I had the classic small boy's fascination with dinosaurs – because they're glamorous, dangerous and extinct – and essentially the appeal of the empires of antiquity is much the same. There's a splendour and a terror about them that appealed to me – and that kind of emotional attachment is something that stays with you."[3]

Holland attended Chafyn Grove preparatory school[4] and the independent Canford School[5] in Dorset. He then went on to Queens' College, Cambridge,[6] graduating with a "double first" (first-class honours in both parts I and II of the course of study in the English Tripos).[7] He began working on a doctoral dissertation on Lord Byron, at Oxford University, but soon quit after deciding that he was "fed up with universities and fed up with being poor"[1] and instead began working.[8]

Writing career

[edit]Novels

[edit]Holland's first books were Gothic horror novels about vampires, set in various time periods throughout history.

His first novel, The Vampyre: Being the True Pilgrimage of George Gordon, Sixth Lord Byron (1995), drew on his knowledge of Lord Byron from his university studies and recast the 19th-century poet as a vampire. It was re-titled Lord of the Dead: The Secret History of Byron for the 1996 U.S. release. The Los Angeles Times called it "a good vampire yarn—elevated and elegant enough to make you feel you needn't conceal it behind the dust jacket of some self-help work, yet happily gory and perilous" although they felt "the newly plowed plot ground is sometimes hurried through as if to get to the scholarly stuff, where the author feels perhaps on more solid ground."[9] Its sequel, Supping with Panthers, was published in 1996 (it was also re-titled for the U.S. release, to Slave of My Thirst).[10]

Holland stayed with the supernatural horror genre for his next few books, continuing to use his knowledge of ancient cultures and settings. In Attis (1996), he took historical figures from the ancient Roman Republic like Pompey and the poet Catullus and put them in a modern setting among a string of brutal murders. He set 1997's Deliver Us From Evil in 17th-century England, with a man named Faustus leading an army of the undead. 1999's Sleeper in the Sands is set in Egypt, starting with the discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922 and travelling backward in time as a deadly secret is unveiled.[8]

Holland's last novel to date departed from the supernatural genre. The Bone Hunter (1999) is a thriller, set in the United States, about the rivalry between two 19th-century paleontologists around whom people begin dying.[11]

Historical non-fiction books

[edit]While doing research for The Bone Hunter, Holland read From Alexander to Actium by historian Peter Green and his childhood passion for ancient history and civilisations was reignited.

All my old fascination with antiquity just went Whoosh! up again. From that moment I started re-immersing myself in that world. I had a sense that antiquity was almost like a science fiction world, that it was utterly remote and yet eerily like our own. I was doing vampire books at the time and it never crossed my mind to write history–but I was finding that my real interests were welling up, and the vampire books were really historical novels, and that I was much less interested in the fiction than in the research.

Despite having no formal qualifications in either Classical Studies or History, he gave up writing fiction and turned to writing history.[3]

His first book of history, Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic, was published in 2003 and garnered positive reviews. It was called "gripping and hugely entertaining" by The Sunday Times,[12] "informative, balanced and accessible" by BookPage,[13] and "a model of exactly how a popular history of the classical world should be written" by The Guardian.[14] Rubicon won the 2004 Hessell-Tiltman Prize, awarded to the best work of non-fiction of historical content.[15] But the book also received reviews of a more negative tone, for example from Professor Ronald J. Weber of the University of Texas:[16]

From the scholar's point of view the question is not whether Rubicon is a good book but whether it is a good history book. It lacks a thorough critical analysis of its primary sources. Also, Holland draws almost exclusively from written accounts, ignoring the physical remains of the period. His account focuses on politics over social and economic trends, and his consideration of the vast amounts of scholarship about the period is limited to a very narrow selection of work. The history students would do better with the 1995 reissue of Erich Gruen's The Last Generation of the Roman Republic. However, for casual readers this story goes well in a favorite chair in front of a warm fire with a hot drink.

Persian Fire (2005) is an account of the 5th-century B.C. Greco-Persian Wars. It was reviewed positively by Paul Cartledge, a professor of Greek history at Cambridge University, for The Independent: "If Persian Fire does not win the Samuel Johnson Prize, there is no justice in this world."[17] Writing in The Sunday Telegraph, historian Dominic Sandbrook called it "riveting" and praised the "enormous strengths" of the author.[18] It won the Anglo-Hellenic League's 2006 Runciman Award.[19]

Millennium: The End of the World and the Forging of Christendom (2008) examines the two centuries either side of the seminal year 1000 A.D., and how Western Europe ascended out of the Dark Ages, to become a leading world civilisation once again. Noel Malcolm reviewed it for The Daily Telegraph and called it "a tremendously good read", but criticised the lack of detail about historical evidence and Holland's "elevated" style of prose.[20] Christina Hardyment, reviewing it for The Independent, praised Holland's writing style, saying he "excels at narration, never jogging when he can gallop ... His highly individual road map to the hitherto 'dark ages' is written with forceful – and convincing – panache."[21]

Holland's book on the rise of Islam, In the Shadow of the Sword (2012), was called "a work of impressive sensitivity and scholarship" by The Daily Telegraph[22] and "a book of extraordinary richness ... For Tom Holland has an enviable gift for summoning up the colour, the individuals and animation of the past, without sacrificing factual integrity" by The Independent.[23] But it was criticised by historian Glen Bowersock in The Guardian as being written in "a swashbuckling style that aims more to unsettle his readers than to instruct them ... irresponsible and unreliable".[24]

Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar (2015) covers the reigns of the five emperors of Rome's Julio-Claudian dynasty, from Augustus to Nero. Professor of Classics at the University of Pennsylvania Emily Wilson, reviewing it for The Guardian, was critical of the "overblown style" and narrative's lurid details, saying, "this is ancient Rome for the age of Donald Trump".[25] But in his review for The Observer, Nick Cohen wrote "Among the many virtues of Tom Holland's terrific history is that he does not shrink from seeing the Roman emperors for what they were: 'the west's primal examples of tyranny'."[26]

Holland next wrote two short historical biographies. The first, Athelstan: The Making of England (2016), is part of the 'Penguin Monarchs' series and covers the life of Æthelstan, the 10th-century ruler regarded as the first king of England.[27] The second, Æthelflæd: England's Forgotten Founder (2019) is an entry in the Ladybird Expert series, and tells of Athelstan's aunt (and daughter of Alfred the Great), Æthelflæd, who ruled the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia in the early 10th century.[28]

Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind (titled Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World for the U.S.), was published in 2019. It is an examination of Christianity's influence on Western civilisation in which Holland maintains that the religion's influence continues to be seen in ethics and cultural norms throughout the world today, even when the religion itself is rejected: "To live in a western country is to live in a society still utterly saturated by Christian concepts and assumptions."[29] Dominion received positive reviews, with Kirkus Reviews calling it "astute and thoughtful",[30] and Publishers Weekly saying that "entertaining is too light a term and instructive is too heavy a term for a rich work that is enjoyably both".[31] Reviewing it for The Times, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of St Andrews Gerard DeGroot argued that much of what Holland attributes to Christian influence is simply humanity evolving the need to work together for survival, but said "I have to commend the originality of this book, not to mention [Holland's] brave ambition."[32]

Other writing

[edit]Holland's translation of The Histories by Herodotus, the ancient Greek scholar, was published in 2013.[33] Although Holland had studied Latin at school, his Greek is completely self-taught, and he set himself the task of translating one paragraph of the over-800-page Histories every day until he finished.[2] Kirkus Reviews called his translation "a feast for students of ancient history and budding historians of any period."[34] Classics scholar Edith Hall reviewed it for The Times Literary Supplement and said it was "unquestionably the best English translation of Herodotus to have appeared in the past half-century, and there have been quite a few ... I am in awe of Tom Holland's achievement."

Holland has written dozens of articles for newspapers, journals and websites on varied topics including wildlife conservation,[35] sports,[36][37] politics[38] and history.[39][40] He also writes occasional book reviews for The Guardian.[41][42][43]

Holland has also written for the stage. His first play, The Importance of Being Frank, told the story of Oscar Wilde's imprisonment and trial. His second was Death of a Maid, which focused on the life of Joan of Arc. In March 2019, he announced on Twitter that he had written an opera about Cleopatra and it was in the showcase stage of development.[44]

Holland was one of the inaugural contributors to the popular Classics website Antigone.[45]

Radio

[edit]Holland adapted the writings of classical Greek and Roman authors Herodotus, Homer, Thucydides, and Virgil for a series of broadcasts on BBC Radio 4.[46] In 2001, Radio Four also broadcast a dramatic play he wrote based on Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War, titled Our Man in Athens. It presented the narrative as that of a veteran war reporter under siege in the studios of Radio Free Athens.[47]

From 2011, he was one of the presenters of Radio 4's popular history series Making History.[48]

Television documentaries

[edit]Dinosaurs, Myths and Monsters

[edit]In February 2011, Holland wrote and presented Dinosaurs, Myths and Monsters, a BBC Four television programme. It explored the influence of fossils on the mythology of various cultures throughout history, including the ancient Greeks and Native Americans.[49]

Islam: The Untold Story

[edit]In August 2012, Holland produced and presented a documentary for Channel 4 television titled Islam: The Untold Story,[50] which questioned Islamic doctrine that maintains Muhammad founded the religion in Mecca in the 7th century, and that the Quran was transmitted, in full, directly to Muhammad by Allah (God) via the angel Gabriel, rather than being written by a person or persons. Holland argued that there is very little contemporary historical evidence about the life of Muhammad, with no mention of him at all in historical texts until decades after his death, and no mention of Mecca in any datable text relating to him until over a century after he died. He concluded that it is much more likely that Islamic theology developed gradually over several centuries as the Arab Empire expanded, and that descriptions of Muhammad's home more closely resemble what is now southern Israel than Mecca.[51][52]

Holland said the program provoked "a firestorm of death threats" against him. Islam: The Untold Story generated more than 1,200 complaints in total to Ofcom and Channel 4,[53][54] though Ofcom found there was no breach of its broadcasting code to investigate.[55] A planned screening of Islam: The Untold Story before an audience of historians was cancelled, due to security concerns over threats received by Holland as a result of the documentary. Several religious scholars, including Dr. Jenny Taylor, founder of the Lapido Media Centre for Religious Literacy in World Affairs, and Dr. Keith Small of the International Qur'anic Studies Association, defended Holland and the right of historians to critically examine the origin stories of religions.[56]

Writing on the Channel 4 website, Holland responded to the criticism by claiming that the origins of Islam is a "legitimate subject of historical enquiry" and that his documentary was "a historical endeavour and is not a critique of one of the major monotheistic religions".[54]

Isis: The Origins of Violence

[edit]In 2017, Holland revisited the topic of Islam by writing and presenting another documentary for Channel 4. Isis: The Origins of Violence looked at the militant terror group ISIS and argued that they use Islamic doctrine to inform and justify their quest for a global caliphate.[57]

In the film, Holland visited the site of the 2015 Bataclan theatre massacre in Paris, interviewed a Salafi jihadist leader in Jordan, and then went to the Iraqi city of Sinjar, which had historically been largely populated by the Yazidi minority. In 2014, ISIS forces swept into the city and killed most of the Yazidi men and old women, taking the young women as sex slaves and the young boys to train as ISIS soldiers. At one point, Holland was shown approaching a pit filled with the remains of Yazidi women whom Isis considered too old to be used as sex slaves, and then had to vomit off-camera.[58]

In an interview with the Evening Standard to promote the film, he said "Just as Nazis justified genocide in terms of racial theory, there are Islamic scholars who justify it in terms of what the Koran says. Not to engage with that, to pretend that's not an issue, is essentially to be complicit in genocide." He also said that westerners are wrong to blame their own foreign policy for the existence of ISIS: "We want to believe we have agency. We want to believe it's about foreign policy — because then we can do something about it. But you just have to read Dabiq [the ISIS magazine]. They say upfront: 'We hate you because you're not Muslim'."[59]

Although some Muslim groups once again registered their disapproval of the programme's content and of Channel 4 for airing it, Holland stated their reaction this time was much less severe than with Islam: The Untold Story.[60] Journalist Peter Oborne wrote a rebuttal to it on the website Middle East Eye titled "No, Channel 4: Islam is not responsible for the Islamic State", in which he stated that the 2003 invasion of Iraq is responsible for ISIS, not Islamic teachings.[61]

Activism

[edit]Conservation

[edit]Holland has campaigned and written articles in support of measures to save London's disappearing hedgehog population.[35][62]

He is an opponent of the proposed Stonehenge road tunnel and other development projects that threaten landscapes around Britain's historic sites and since 2018 has been president of the Stonehenge Alliance, a group dedicated to stopping construction of the tunnel (or at least convincing the government to redesign it from the planned 1.8 miles in length to a longer, deep bored tunnel of at least 2.8 miles that would be less obtrusive to the World Heritage Site).[63][64] In 2017, he said of the Stonehenge tunnel: "The issue is whether Stonehenge exists to provide a tourist experience, or whether it is something more significant, both historically and spiritually. It has stood there for 4,500 years. And up to now, no one's thought of injecting enormous quantities of concrete into the landscape and permanently disfiguring it."[65]

Politics

[edit]In August 2014, Holland and fellow historian Dan Snow organised 200 British public figures in signing a letter to the people of Scotland, published by The Guardian, expressing the hope that Scotland would vote to remain part of the United Kingdom in the September 2014 referendum on that issue. The letter read in part "We want to let you know how very much we value our bonds of citizenship with you, and to express our hope that you will vote to renew them. What unites us is much greater than what divides us. Let's stay together." Among the signatories were Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber, Mick Jagger, Dame Judi Dench and Stephen Hawking.[66]

Earlier that year, he had voiced his desire for the United Kingdom to stay a part of the European Union, saying: "I would like to remain a citizen of the European Union, but I would like even more to continue in a country that includes Scotland ... the likelier it seems the United Kingdom will leave the EU, the likelier Scotland is to leave the United Kingdom. I don't want to be a Little Englander. I want to stay European, and I want to stay British."[67] After Britain voted to leave the EU in 2016, Holland stated that he himself had voted Remain, but that since Brexit had been chosen by the people in a democratic vote, the government had to carry through with it. He posted on his Twitter account in October 2018: "Brexit has to happen – anything else would be undemocratic. But the result was close, close, close – so the Brexit settlement should properly accept that. I'm sure that's what most people feel."[68]

In 2017, Holland joined Scottish businessman/blogger Kevin Hague and history professor Ali Ansari to create a new think tank which they named "These Islands". It is devoted to stimulating positive debate about Britain's identity, Brexit and the Scottish independence issue, and promoting the idea that staying united as a nation is beneficial to all the countries that make up Great Britain. A number of academics and activists have contributed papers to the These Islands website.[69][70]

In 2019, Holland was a signatory on a public letter to The Guardian denouncing Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the Labour Party and candidate for Prime Minister, for antisemitism.[71] In an article for The Telegraph, he wrote that Corbyn's support for Palestinian activist Raed Salah was particularly offensive to him due to Salah's spread of the blood libel, which originated in England in the 12th century: "England, as the birthplace of this most toxic of lies, has a particular responsibility to take a stand against it. Taking a stand against it, however, is something that Jeremy Corbyn, by backing a promoter of the blood libel, has failed to do."[72]

Yazidi

[edit]While filming Isis: Origins of Evil, Holland interviewed Yazidi refugees, survivors of an ethnoreligious population of northern Iraq who in 2014 suffered the mass murder of many of their men and older women, and the kidnapping of their children and young women, by ISIS. In 2017, he wrote an article for The Spectator in which he implored the Western world not to forget the Yazidi. In it, he detailed what ISIS had inflicted upon the Yazidi:

"Yazidis [were] shot and thrown like refuse into pits; men and boys beheaded in front of their families; girls as young as eight subjected to gang rape; beatings; forced conversions; torture; slavery. In a camp I visited, a woman who had been raped for an entire year, then shot in the head when her owner grew tired of her, then finally sold back to her husband, lay curled in a foetal ball in a makeshift tent, rocking and moaning to herself."[73]

In June 2018, he gave an interview to James Delingpole on the latter's podcast and spoke about Western apathy toward the Yazidis' suffering: "Nobody in the West really gives a shit. And the reason nobody gives a shit, as a Yazidi refugee I spoke to said, is that in the West you have Christians, you have Muslims, you have Jews who all speak up for their co-religionists, but who cares about the Yazidi? Who cares about them?"[74]

In June 2019, he joined several other speakers in addressing an assembly of members of Parliament in the Grand Committee room of the House of Commons,[75] where he spoke about the cruelties inflicted upon the Yazidi.[76]

Antisemitism

[edit]Holland has written about historical antisemitism in England. He has also argued that one can draw connections between it and more recent antisemitic attitudes expressed by members of the British Labour Party under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn.[77]

Views

[edit]Education

[edit]Holland has been a proponent of state education over private, saying in 2014:

The wealth that the leading [independent] schools can call upon has become obscene. How can state-funded schools possibly compete with sports fields and state-of-the-art facilities that have seen sport, acting and even popular music dominated by the privately educated? Which said, I am not convinced that the teaching in private schools is any better than in state schools. Our local primary school has teachers as good as any you could hope to meet, and when I compare the start that it has given my children to that given to the prep-school pupils I know, I do not remotely feel that my children have come off second-best. Just the opposite, in fact.[67]

He supported the plan by Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove to spread the teaching of Latin in state schools, saying in 2014:

Traditionally, an education in ancient languages has served as a marker of privilege – which is why public schools have always been so keen on providing it. I don't see, though, why children should be deprived of the riches of classical civilisation, just because they are in the state system ... It is not an elitist policy but the precise opposite: impeccably progressive.[67]

Christianity

[edit]Although his father is an atheist, Holland was raised in the Christian church by his "devout Anglican" mother, and he said in 2013 that because of her example "I've always associated Anglicanism with goodness and decency and generosity of spirit and compassion, so I never had that visceral association of Christianity or institutional religion with repression or dogma or illiberalism."[78] Nonetheless, as an adult he disavowed belief in the existence of God, saying "I have seen no evidence that would satisfy me that anything supernatural exists. I have seen no proof for god [sic]."[78]

In 2016, he wrote an article titled "Why I Was Wrong About Christianity" for the New Statesman, in which he said that he had come to realise he was incorrect to have thought in the past that his own western values derived from the Greece and Rome of antiquity and owed nothing to Christianity:

Familiarity with the biblical narrative of the crucifixion has dulled our sense of just how completely novel a deity Christ was ... [Christianity] is the principal reason why, by and large, most of us who live in post-Christian societies still take for granted that it is nobler to suffer than to inflict suffering. It is why we generally assume that every human life is of equal value. In my morals and ethics, I have learned to accept that I am not Greek or Roman at all, but thoroughly and proudly Christian.[79]

On July 2, 2024, The Times published a letter to the editor, co-signed by Holland and numerous other Catholic and non-Catholic public figures, calling upon the Holy See to preserve what they describe as the "magnificent" cultural artifact of the Catholic Church's Traditional Latin Mass.[80]

Islam and the Islamic State

[edit]He has defended himself from critics who have suggested that his views on Islam and its origins are rooted in Islamophobia, saying that he merely believes Islam should receive the same kind of historical analysis that other religions do. In 2013, he said in an interview with The Daily Telegraph: "Islam is like a shot of caffeine into British culture. It adds a new dimension to the world, it enriches the variety and scope of our intellectual life."[33]

In March 2015, Holland published a piece titled "We must not deny the religious roots of Islamic State" in the New Statesman. It argued that the jihadis of ISIS call themselves Islamic and use text from the Quran to justify their actions, so therefore, people like the writer Mehdi Hasan ought not to claim they are not Muslims, as Hasan had in the previous week's issue. Holland wrote that "It is not merely coincidence that ISIS currently boasts a caliph, imposes quranically mandated taxes, topples idols, chops the hands off thieves, stones adulterers, executes homosexuals and carries a flag that bears the Muslim declaration of faith."[81] In 2017, he said "The mistake people make is to replicate Isis's position, which is that there's one, true form of Islam and anyone who deviates from that isn't a Muslim. That's Isis's justification for killing Shia. Ironically, when Western leaders say 'it's nothing to do with Islam', they're doing the same. I don't think it's the business—particularly of non-Muslims—to specify what a Muslim is. If people say they're Muslim, they're Muslim."[59]

In May 2015, Holland gave the inaugural Christopher Hitchens Lecture at the Hay Festival, in which he addressed the subject of De-Radicalising Muhammad.[82] In an interview he gave to the literary website Quadrapheme the following month he explained that he wanted the lecture to promote discussion of the way Muhammad's life is interpreted, arguing that his "mythos lies at the core of what is pernicious in the goings-on of Islamic State and other radicals."[83]

Personal life

[edit]Holland married Sadie, a midwife,[2] on 31 July 1993.[84] The couple have two daughters[2] and live in Brixton, London.[1]

He is the great-nephew of Olympic cyclist Charles Holland,[85] the first Englishman to complete the Tour de France.[86] He is not related to actor Tom Holland.

Holland is a prolific user of the social media site Twitter. He joined the site in January 2011 and, as of September 2024, had sent out over 225,000 tweets.[87]

In 2016, Holland was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.[88]

He is a keen cricket fan and player and a bowler (medium-slow) for the Authors XI team, which is composed of prominent British writers. He contributed a chapter to The Authors XI: A Season of English Cricket from Hackney to Hambledon, a 2013 book collectively written by the team about their first season playing together.[89] He also wrote an article for the Financial Times about receiving batting training from his cricketing hero, Alastair Cook.[90]

Written works

[edit]Series fiction

[edit]- Holland, Tom (1995). The Vampyre: Being the True Pilgrimage of George Gordon, Sixth Lord Byron (published in the U.S. as Lord of the Dead). London: Hachette UK. ISBN 0-316-91227-1.

- ——— (1996). Supping with Panthers (published in the U.S. as Slave of My Thirst). London: Hachette UK. ISBN 0-316-87622-4.

Fiction

[edit]- Holland, Tom (1995). Attis. London: Allison & Busby. ISBN 0-7490-0213-1.

- ——— (1997). Deliver Us From Evil. London: Time Warner Books. ISBN 0-316-88248-8.

- ——— (1998). The Sleeper in the Sands. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-64480-3.

- ——— (2001). Bonehunter. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-64819-1.

Short fiction

[edit]- Holland, Tom (2006). The Poison in the Blood. London: Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11964-3.

Plays

[edit]- Holland, Tom (1997). The Importance of Being Frank. London: Favell & Marsden. ISBN 0-953-05871-9.

Non-fiction

[edit]- Holland, Tom (2003). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-400-07897-4.

- ——— (2005). Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-27948-4.

- ——— (2008). Millennium: The End of the World and the Forging of Christendom. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-27870-8.

- ——— (2012). In the Shadow of the Sword: The Battle for Global Empire and the End of the Ancient World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-408-70007-5.

- ——— (2015). Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-385-53784-1.

- ——— (2016). Athelstan: The Making of England. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-241-18781-4.

- ——— (2019). Æthelflæd: England's Forgotten Founder. illus. Colin Shearing. London: Ladybird Books. ISBN 978-0-7181-8826-9.

- ——— (2019). Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind (U.S. edition subtitled 'How the Christian Revolution Remade the World'). London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-408-70695-4. Description & arrow-searchable preview.

- ——— (2023). Pax: War and Peace in Rome's Golden Age. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-349-14616-4.

Translation

[edit]- Herodotus (2013). The Histories. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-143-10754-5.

Radio broadcasts

[edit]- Our Man in Athens (writer) 30 July 2001, Radio 4

- Making History (presenter) 2011–2020, Radio 4

Television broadcasts

[edit]- Dinosaurs, Myth and Monsters (writer and presenter) 14 September 2011, BBC Four

- Islam: The Untold Story (writer and presenter) 28 August 2012, BBC Four

- Isis: Origins of Violence (writer and presenter) 17 May 2017, BBC Four

Podcast

[edit]Holland presents a podcast with historian Dominic Sandbrook, called The Rest is History.[91]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Dodds, Georges (June 1999). "A Conversation with Tom Holland". The SF Site. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d Higgins, Charlotte (28 August 2015). "Tom Holland interview: Caligula, vampires and coping with death threats". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b Robinson, David (7 April 2019). "Interview: Tom Holland, author of In the Shadow of the Sword". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Robson, Linda (2017). "Milford—Chafyn Grove School" (PDF). Wiltshire OPC. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ "Canfordian 2017". issuu. 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ 'HOLLAND, Thomas (born 5 January 1968)' in Who's Who 2013

- ^ "Tom Holland: Senior Research Fellow in Ancient History". The University of Buckingham Humanities Research Institute. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ a b Mathew, David (February 1999). "Vampires, Sand and Horses". Infinity Plus. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Morrison, Patt (25 February 1999). "Mad, Bad and Dangerous : FICTION : LORD OF THE DEAD: The Secret History Of Byron, By Tom Holland". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Clarke, Roger (24 August 1996). "Book Review / Vaudevillian vampires and the scent of baloney". The Independent. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (1999). The Bone Hunter. Little, Brown. ISBN 9780748131075.

- ^ Frederic, Raphael (17 August 2003). "Review: Ancient history: Rubicon by Tom Holland". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Watts, Justin (February 2004). "Rubicon: Tom Holland". BookPage. Retrieved 29 April 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Miles, Richard (7 November 2003). "What the Romans did last". Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ "Hessell-Tiltman Prize". English PEN. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Weber, Ronald J. (2004). "Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic, History: Reviews of New Books". History: Reviews of New Books. 32 (4): 166 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ Cartledge, Paul (2 September 2005). "Persian Fire: The first world empire and the battle for the west, by Tom Holland". independent.co.uk.

- ^ Sandbrook, Dominic (18 September 2015). "A civilising influence – Dominic Sandbrook reviews Persian Fire by Tom Holland". telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Two Runciman winners named". Kathimerini. 6 August 2006. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel (3 October 2008). "Review: Millennium by Tom Holland". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Hardyment, Christina (10 October 2008). "Millennium by Tom Holland". The Independent. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Jones, Dan (5 April 2012). "In the Shadow of the Sword by Tom Holland: review". Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ Rogerson, Barnaby (30 March 2012). "In The Shadow of the Sword, By Tom Holland". Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ Bowersock, Glen (4 May 2012). "In the Shadow of the Sword by Tom Holland – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Emily (29 October 2015). "Dynasty by Tom Holland review: The soap opera version of history". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Cohen, Nick (6 September 2015). "Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar review – deft and skillful". The Observer. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (2016). Athelstan: the Making of England. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0241187814.

- ^ Holland, Tom (2019). Æthelflæd: England's Forgotten Founder. Penguin Random House UK. ISBN 978-0718188269.

- ^ Holland, Tom (2019). Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1408706954.

- ^ "Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World by Tom Holland". Kirkus Reviews. 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World". Publishers Weekly. October 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ DeGroot, Gerard (23 August 2019). "Dominion by Tom Holland review — are we all children of the Christian revolution?". The Times. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ a b Rahim, Sameer (6 October 2013). "Tom Holland: 'The Histories are a great shaggy-dog story'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "The Histories by Herodotus, translated by Tom Holland". Kirkus Reviews. 19 May 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ a b Holland, Tom (30 March 2017). "A prickly tale: historian Tom Holland on his quest to save the hedgehog vanishing from London life". Evening Standard. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (9 October 2014). "Kevin Pietersen is a hero for our age: Beowulf, Achilles and Lancelot in one". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (June 2014). "Of Myths and Origins" (PDF). Nightwatchman. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (10 November 2018). "Decline and fall: why America always thinks it's going the way of Rome". The Spectator. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (9 April 2019). "Britain's First Brexit was the Hardest". Unherd. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (28 February 2019). "The Romans took their graffiti seriously – especially the phalluses". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (19 January 2019). "The Wall by John Lanchester review – 'The Others are coming'". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (25 September 2010). "The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt by Toby Wilkinson; Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt by Joyce Tyldesley; and Egyptian Dawn by Robert Temple". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (17 April 2019). "The Dinosaurs Rediscovered review – a transformation in our understanding". Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ @Holland_Tom (11 March 2019). "Huge Excitement" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Caesars and Sopranos: The Shadow of Suetonius". 10 March 2021.

- ^ Miles, Richard (8 November 2003). "Review: Rubicon by Tom Holland". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ OUR MAN IN ATHENS, retrieved 5 July 2019

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 – Making History, 15/11/2011". BBC. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "Dinosaurs, Myths and Monsters". BBC. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Islam – The Untold Story". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ Holland, Tom (8 January 2015). "Viewpoint: The roots of the battle for free speech". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ kern, soeren (21 September 2012). "Britain: Islam Documentary Cancelled Amid Threats of Physical Violence". Gatestone Institute. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ O'Carroll, Lisa (3 September 2012). "Channel 4 documentary Islam: The Untold Story receives 1,200 complaints". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Channel 4's Islam film sparks row". BBC News. 3 September 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Sweney, Mark (8 October 2012). "Ofcom will not investigate Channel 4 documentary on origins of Islam". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Taylor, Jenny (5 September 2012). "Tom Holland's Islam Film: The Scholar vs. the Booby". Lapido Media. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Mark Lawson (17 May 2017). "Isis: The Origins of Violence – a brave documentary that will start many a fight". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ Murray, Douglas (18 May 2017). "The British broadcaster brave enough to discuss Islamic violence". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ a b Urwin, Rosamund (17 May 2017). "Historian Tom Holland on Isis, receiving death threats and why there is a 'civil war' in the Muslim world". Evening Standard. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Marshall, Tim (26 May 2017). "An Interview With...Tom Holland". The What & the Why. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Oborne, Peter (25 July 2017). "No, Channel 4: Islam is not responsible for the Islamic State". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (9 September 2018). "If we love hedgehogs so much, why are we letting them vanish?". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "About us". Stonehenge Alliance. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ "What we are campaigning for". Stonehenge Alliance. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Harris, John (25 April 2017). "The Stonehenge tunnel: 'A monstrous act of desecration is brewing'". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Celebrities' open letter to Scotland – full text and list of signatories". The Guardian. London. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Holland, Tom (7 February 2014). "The Big Questions: Should Latin be taught in state schools? Is flooding in the UK a fact of life? Should Tube workers have gone on strike?". The Independent. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ @Holland_Tom (20 October 2018). "Brexit has to happen" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Studemann, Frederick (8 November 2017). "Brexit and Britain's fraught democratic experiment". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ "These Islands: Uniting Not Dividing". These Islands. 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Mason, Rowena; Perraudin, Frances (14 November 2019). "Labour antisemitism row: public figures say they cannot vote for party under Corbyn". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ Tom Holland (16 November 2019). "As a historian of England's shameful anti-Semitic past, I dread the idea of Prime Minister Corbyn". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (12 August 2017). "Don't forget the Yazidis: To avoid the next genocide, remember the last". Spectator. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Delingpole: Tom Holland – author, historian". Podtail. 7 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Plight of the Yezidi people: an unlamented & unresolved genocide – HoC". eventbrite. 25 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Tugendhat, Tom (25 June 2019). "Listening to @holland_tom talk about the brutal murder, enslavement and torture of the Yazidi people is deeply moving. The cruelty shown to these people cries out for justice and that starts with recognition.pic.twitter.com/9fAEEkhhif". @TomTugendhat. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Tom Holland (16 November 2019). "As a historian of England's shameful anti-Semitic past, I dread the idea of Prime Minister Corbyn". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ a b Shaha, Alom (20 December 2013). "'Secularism is Christianity's greatest gift to the world'". New Humanist. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (14 September 2016). "Tom Holland: Why I was wrong about Christianity". New Statesman. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Letters to the editor". The Times. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ newstatesman.com: "Tom Holland: We must not deny the religious roots of Islamic State", 17 March 2015

- ^ "Tom Holland". Hay Festival. 25 May 2015.

- ^ "Mission Impossible? An Interview with Tom Holland | Quadrapheme". www.quadrapheme.com. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ Holland, Tom (30 July 2019). "Massively looking forward to celebrating my 26th wedding anniversary tomorrow with @sadieholland67 by walking London's sleaziest vanished river, the #Neckinger". @holland_tom. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ Holland, Tom (2 August 2019). "Listening to my father talk about his Uncle Charlie, the second best #EliteInternationalSportsman in the Holland family, I discover to my astonishment & pride that he once had a trial for @AVFCOfficial!!!!!!". Twitter. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Bingham, Keith (27 September 2007). "TOUR TIME CAPSULE FOUND IN ATTIC". Cycling Weekly. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Tom Holland". Twitter. September 2024. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ "Tom Holland". The Royal Society of Literature. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Authors Cricket Club (2013). The Authors XI: A Season of English Cricket from Hackney to Hambledon. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4088-4045-0.

- ^ Holland, Tom (15 November 2013). "FT Masterclass: Batting with Alastair Cook". Financial Times. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ Cunliffe, Rachel (20 April 2022). "The Rest is History is breathtaking in its scope". New Statesman. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- The Rest is History podcast

- Holland's page Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Conville and Walsh literary agents

- These Islands website

- 1968 births

- Living people

- Alumni of Queens' College, Cambridge

- Alumni of the University of Oxford

- 21st-century English historians

- English podcasters

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- History Today people

- People educated at Canford School

- People educated at Chafyn Grove School

- People from Salisbury

- Runciman Award winners