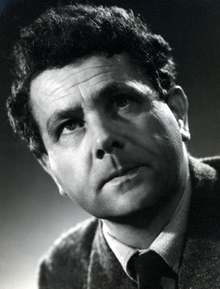

Gerald Finzi

Gerald Raphael Finzi (14 July 1901 – 27 September 1956) was a British composer. Finzi is best known as a choral composer, but also wrote in other genres. Large-scale compositions by Finzi include the cantata Dies natalis for solo voice and string orchestra, and his concertos for cello and clarinet.

Life

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2023) |

Gerald Finzi was born in London, the son of John Abraham (Jack) Finzi and Eliza Emma (Lizzie) Leverson. Finzi became one of the most characteristically English composers of his generation. Despite his being an agnostic of Jewish descent, several of his choral works incorporate Christian texts.

Finzi's father, a successful shipbroker, died a fortnight before his son's eighth birthday.[1] Finzi was educated privately. During World War I the family settled in Harrogate, and Finzi began to study music at Christ Church, High Harrogate, under Ernest Farrar from 1915.[2] Farrar, a former pupil of Charles Villiers Stanford, was then aged thirty and he described Finzi as "very shy, but full of poetry".[2] Finzi found him a sympathetic teacher,[2] and Farrar's death at the Western Front affected him deeply.

During those formative years, Finzi also suffered the loss of all three of his brothers, adversities that contributed to Finzi's bleak outlook on life.[3] He found solace in the poetry of Thomas Traherne and his favourite, Thomas Hardy, whose poems, as well as those by Christina Rossetti, he began to set to music. In the poetry of Hardy, Traherne, and later William Wordsworth, Finzi was attracted by the recurrent motif of the innocence of childhood corrupted by adult experience. From the very beginning most of his music was elegiac in tone.

Finzi was, at one time, a vegetarian but gave it up and favoured eggs, fish and sometimes bacon or chicken.[4]

1918–33: Studies and early compositions

[edit]After Farrar's death, Finzi studied privately at York Minster with the organist and choirmaster Edward Bairstow, a strict teacher compared with Farrar. In 1922, after five years of study with Bairstow, Finzi moved to Painswick in Gloucestershire, where he began composing in earnest. His first Hardy settings, and the orchestral piece A Severn Rhapsody, were soon performed in London to favourable reviews.

In 1925, at the suggestion of Adrian Boult, Finzi took a course in counterpoint with R. O. Morris and then moved to London, where he became friendly with Howard Ferguson and Edmund Rubbra.[5] He was also introduced to Gustav Holst, Arthur Bliss and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Vaughan Williams obtained a teaching post (1930–1933) for him at the Royal Academy of Music.

1933–39: Musical development

[edit]Finzi never felt at home in London and, having married the artist Joyce Black, settled with her in Aldbourne, Wiltshire, where he devoted himself to composing and apple-growing, saving a number of rare English apple varieties from extinction. He also amassed a large library of some 3,000 volumes of English poetry, philosophy and literature, which is now kept at the University of Reading. His collection of about 700 volumes of 18th-century English music, including books, manuscripts and printed scores, is now held by the University of St Andrews.[6]

During the 1930s, Finzi composed only a few works, but it was in them, notably the cantata Dies natalis (1939) to texts by Thomas Traherne, that his fully mature style developed. He also worked on behalf of the poet-composer Ivor Gurney, who had been committed to a mental hospital. Finzi and his wife catalogued and edited Gurney's works for publication. They also studied and published English folk music and music by older English composers such as William Boyce, Capel Bond, John Garth, Richard Mudge, John Stanley and Charles Wesley.

In 1939, the Finzis moved to Ashmansworth in Hampshire, where he founded the Newbury String Players, an amateur chamber orchestra that he conducted until his death, reviving 18th-century string music, as well as giving premieres of works by his contemporaries and offering talented young musicians such as Julian Bream and Kenneth Leighton the chance to perform.

1939–56: Growth of reputation

[edit]The outbreak of World War II delayed the first performance of Dies natalis at the Three Choirs Festival, an event that could have established Finzi as a major composer. He was directed to work at the Ministry of War Transport and lodged German and Czech refugees in his home. After the war, he became somewhat more productive than before, writing several choral works as well as the Clarinet Concerto (1949), perhaps his most popular work today.

By then, Finzi's works were being performed frequently at the Three Choirs Festival and elsewhere. But that happiness was not to last. In 1951, he learned that he was suffering from the then incurable Hodgkin's disease and had ten years to live, at most. His feelings after that revelation are probably reflected in the agonized first movement of his Cello Concerto (1955), Finzi's last major work. However its second movement, originally intended as a musical portrait of his wife, is more serene.

In 1956, following an excursion near Gloucester with Vaughan Williams, Finzi developed shingles, probably as a result of immune suppression caused by Hodgkin's disease. Biographies refer to him subsequently developing chickenpox, which developed into a "severe brain inflammation". That probably means that his shingles developed into disseminated shingles, which resembles chickenpox, and was complicated by encephalitis. He died soon afterwards, aged 55, in the Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, the first performance of his Cello Concerto having been given on the radio the night before. His ashes were scattered on May Hill near Gloucester in 1973.[7]

Works

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2023) |

Finzi’s output includes nine song cycles, six of them on the poems of Thomas Hardy. The first of these, By Footpath and Stile (1922), is for voice and string quartet; the others, including A Young Man’s Exhortation and Earth and Air and Rain, for voice and piano. Among his other songs, the settings of Shakespeare poems in the cycle Let Us Garlands Bring (1942) are the best known. He also wrote incidental music to Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost (1946). For voice and orchestra he composed the above-mentioned Dies natalis, and the pacifist Farewell to Arms (1944).

Finzi’s choral music includes the popular anthems Lo, the full, final sacrifice and God is gone up as well as unaccompanied partsongs, but he also wrote larger-scale choral works such as For St. Cecilia (text by Edmund Blunden), Intimations of Immortality (William Wordsworth) and the Christmas scene In terra pax (Robert Bridges and the Gospel of Luke), all from the last ten years of his life.

The number of Finzi’s purely instrumental works is small even though he took great pains over them in the early part of his career. He began what is believed to have been intended as a piano concerto. This was never finished or given a title, but after his death his publisher gave two of the individual movements names and published them as the separate works Eclogue and Grand Fantasia and Toccata. The latter demonstrates Finzi’s admiration for Johann Sebastian Bach as well as the Swiss-American composer Ernest Bloch. He also completed a violin concerto which was performed in London under the baton of Vaughan Williams, but was not satisfied with it and withdrew the two outer movements; the surviving middle movement is called Introit. This concerto thus received only its second performance in 1999 and its first recording is now on Chandos. Finzi's Clarinet Concerto and his Cello Concerto are possibly his most famous and frequently performed instrumental works, with recordings of these works done by clarinetist John Denman and a young Yo-Yo Ma.

Of Finzi's few chamber works, only the Five Bagatelles for clarinet and piano, published in 1945, have survived in the regular repertoire. The Prelude and Fugue for string trio (1938) is his only piece for string chamber ensemble. It was written as a tribute to R O Morris, and shares the austere and melancholy mood of his teacher's music.[8]

Finzi had a long-standing friendship with the composer Howard Ferguson who, as well as offering advice on his works during his life, helped with the editing of several of Finzi's posthumous works.

Legacy

[edit]Finzi's elder son, Christopher, became a conductor and exponent of his father's music. Finzi's younger son Nigel was a violinist, and worked closely with their mother in promoting his father's music.[9]

References

[edit]This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2009) |

- ^ McVeagh, p. 6

- ^ a b c McVeagh, p. 9

- ^ Jupin, Richard Michael (December 2005). "GERALD FINZI AND JOHN IRELAND: A STYLISTIC COMPARISON OF COMPOSITIONAL APPROACHES IN THE CONTEXT OF TEN SELECTED POEMS BY THOMAS HARDY". Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College.

- ^ McVeagh, Diana. (2013). Gerald Finzi: His Life and Music. Boydell Press. p. 74; ISBN 978-1843836025

- ^ Michael Hurd and Howard Ferguson (ed). Letters of Gerald Finzi and Howard Ferguson (2001)

- ^ "Finzi Collection". University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Diana M. McVeagh: Gerald Finzi: his life and music (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2005), p. 251.

- ^ 'British String Trios', reviewed at MusicWeb International

- ^ McVeagh, Diana (2005). Gerald Finzi: His Life and Music. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. p. 72. ISBN 1843836025.

- Banfield, Stephen. Gerald Finzi: An English Composer (Faber, 1997) ISBN 0-571-16269-X

- Dressler, John C. Gerald Finzi: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood, 1997) ISBN 0-313-28693-0

- Jordan, Rolf. The Clock of the Years: A Gerald and Joy Finzi Anthology (Chosen Press, 2007) ISBN 978-0-9556373-0-8

- McVeagh, Diana. Gerald Finzi: His Life and Music (Boydell, 2006) ISBN 1-84383-170-8

External links

[edit]- The official Gerald Finzi website, created for the composer's family and including latest news of concerts featuring Finzi's works.

- A Finzi page on the website of his publisher Boosey & Hawkes, including a complete list of works published by Boosey & Hawkes and a discography.

- A Finzi Page at MusicWeb International by John France.

- The Finzi Trust, the official Finzi Trust website: listen to Finzi's music and read about his life and works, the Trust's work and the Finzi Travel Scholarships.

- Finzi Friends

- "Gerald Finzi: the quiet man of British classical music" -article by Mark Padmore in The Guardian

- Free scores by Gerald Finzi at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- 1901 births

- 1956 deaths

- 20th-century British classical composers

- English classical composers

- Jewish classical composers

- Jewish agnostics

- Jewish English musicians

- English people of German-Jewish descent

- English people of Italian-Jewish descent

- Academics of the Royal Academy of Music

- People associated with the University of Reading

- People from Ashmansworth

- Musicians from London

- Compositions by Gerald Finzi

- Deaths from varicella zoster infection

- 20th-century English musicians

- Choral composers