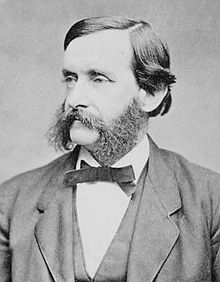

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from the 1st Middlesex district | |

| In office January 7, 1880 – January 4, 1882 Serving with George W. Park (1880) and Henry W. Muzzey (1881) | |

| Preceded by | Edwin B. Hale |

| Succeeded by | Chester W. Kingsley |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 22, 1823 Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | May 9, 1911 (aged 87) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Free Soil (1850–51) Republican Democratic (1888) |

| Occupation | Minister, author, soldier |

| Signature | |

Thomas Wentworth Higginson (December 22, 1823 – May 9, 1911), who went by the name Wentworth,[1]: 52 was an American Unitarian minister, author, abolitionist, politician, and soldier. He was active in abolitionism in the United States during the 1840s and 1850s, identifying himself with disunion and militant abolitionism. He was a member of the Secret Six who supported John Brown. During the Civil War, he served as colonel of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, the first federally authorized black regiment, from 1862 to 1864.[2] Following the war, he wrote about his experiences with African-American soldiers and devoted much of the rest of his life to fighting for the rights of freed people, women, and other disfranchised peoples. He is also remembered as a mentor to poet Emily Dickinson.

Early life and education

[edit]Higginson was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on December 22, 1823. He was a descendant of Francis Higginson, a Puritan minister and one of the original settlers of the colony of Massachusetts Bay.[3] His father, Stephen Higginson (born in Salem, Massachusetts, November 20, 1770; died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, February 20, 1834), was a merchant and philanthropist in Boston and bursar of Harvard University from 1818 until 1834. Through his mother he was related to Boston's influential Storrow family.[1]: 52 His grandfather, also named Stephen Higginson, was a member of the Continental Congress. He was a distant cousin of Henry Lee Higginson, founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, a great grandson of his grandfather.[4] A third great grandfather was New Hampshire Lieutenant-Governor John Wentworth.[5]

Education and abolitionism

[edit]Higginson entered Harvard College at age thirteen and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa at sixteen.[6] He graduated in 1841 at age 18 and taught at a private school for four months, but he detested it and became "a tutor of the three children of his Brookline cousin, Stephen Higginson Perkins".[7][3] After that, in 1843, he became "a nonmatriculated student at Harvard".[8] In 1842 he became engaged to Mary Elizabeth Channing.

He then studied theology at the Harvard Divinity School. In 1845, at the end of his first year of divinity training, he withdrew from the school to turn his attention to the abolitionist cause. He spent the subsequent year studying and, following the lead of Transcendentalist Unitarian minister Theodore Parker, fighting against the expected war with Mexico. Believing that war was only an excuse to expand slavery and the Slave Power, Higginson wrote antiwar poems and went door to door to get signatures for antiwar petitions. With the split of the antislavery movement in the 1840s, Higginson subscribed to the Disunion Abolitionists, who believed that as long as slave states remained a part of the Union, the Constitution could never be amended to ban slavery.

Marriage and family

[edit]Higginson re-entered divinity school, and after graduating in 1847 and being ordained as the minister of a Newburyport Unitarian church (see below), he married Mary Channing.[9] Mary was the daughter of Dr. Walter Channing, a pioneer in the field of obstetrics and gynecology who taught at Harvard University, the niece of Unitarian minister William Ellery Channing, and the sister of Henry David Thoreau's friend Ellery Channing. Higginson and Mary Channing had no children but raised Margaret Fuller Channing, the eldest daughter of Ellen Fuller and Ellery Channing. Ellen was the sister of the Transcendentalist and feminist author, Margaret Fuller.[10] Mary Channing died in 1877. Two years later Higginson married Mary Potter Thacher, with whom he had two daughters, one of whom survived into adulthood.[11]

Higginson was also related to Harriet Higginson, whose Wooddale, Illinois, home was the first commission of famed architect Bertrand Goldberg in 1934.

Career

[edit]Ministry

[edit]Having graduated from divinity school, Higginson was called as pastor at the First Religious Society of Newburyport, Massachusetts, a Unitarian church known for its liberal Christianity.[12][13] He supported the Essex County Antislavery Society and criticized the poor treatment of workers at Newburyport cotton factories. Additionally, the young minister invited Theodore Parker and fugitive slave William Wells Brown to speak at the church, and in sermons he condemned northern apathy towards slavery. In his role as board member of the Newburyport Lyceum and against the wishes of the majority of the board, Higginson brought Ralph Waldo Emerson to speak.[14] Higginson proved too radical for the congregation and resigned in 1849.[15][16] After that, he lectured on the Lyceum circuit, initially receiving about $15 for each talk (Theodore Parker and Ralph Waldo Emerson could command $25).[17]

Politics and militant abolitionism

[edit]The Compromise of 1850 brought new challenges and new ambitions for the unemployed minister. He ran as the Free Soil Party candidate for Massachusetts's 3rd congressional district in 1850 but lost. Higginson called upon citizens to uphold God's law and disobey the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

He joined the Boston Vigilance Committee, an organization whose purpose was to protect fugitive slaves from pursuit and capture.[16] His joining of the group was inspired by the arrest and trial of the free black Frederick Jenkins, known as Shadrach. Abolitionists helped him escape to Canada. He participated with Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker in the attempt at freeing Thomas Sims, a Georgia slave who had escaped to Boston. In 1854, when the escaped Anthony Burns was threatened with extradition under the Fugitive Slave Act, Higginson led a small group who stormed the federal courthouse in Boston with battering rams, axes, cleavers, and revolvers.[6] They could not prevent Burns from being taken back to the South. A courthouse guard was killed, proof that "war had really begun."[18]: 85 Higginson received a saber slash on his chin; he wore the scar proudly for the rest of his life.[18]: 85

In 1852, Higginson became pastor of the "fervently anti-slavery" Free Church in Worcester.[18]: 85 During his tenure, Higginson not only supported abolition, but also temperance, labor rights, and rights of women.

Returning from a voyage to Europe for the health of his wife, who had an unknown illness, Higginson organized a group of men on behalf of the New England Emigration Aid Company to use peaceful means as tensions rose after the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. The act divided the region into the Kansas and Nebraska territories, whose residents would separately vote on whether to allow slavery within each jurisdiction's borders. Both abolitionist and pro-slavery supporters began to migrate to the territories. After his return, Higginson worked to keep activism aroused in New England by speechmaking, fundraising, and helping to organize the Massachusetts State Kansas Committee. He returned to the Kansas territory as an agent of the National Kansas Aid Committee, working to rebuild morale and distribute supplies—crates of rifles, revolvers, knives, ammunition, and a cannon[18]: 85 —to settlers. Higginson became convinced that abolition could not be attained by peaceful methods.[19][20] He celebrated Kansas as the equivalent of Bunker Hill; he called it a rehearsal for the violence to come.[18]: 85

As sectional conflict escalated, he continued to support disunion abolitionism, organizing the Worcester Disunion Convention in 1857, favoring the North's secession from the slave-holding South and federal government. The convention asserted abolition as its primary goal, even if it would lead the country to war. Higginson was a fervent supporter of John Brown and is remembered as one of the "Secret Six" abolitionists who helped Brown raise money and procure supplies for his intended slave insurrection at Harper's Ferry, West Virginia. When Brown was captured, Higginson tried to raise money for a trial defense and made plans to help the leader escape from prison, though he was ultimately unsuccessful. Other members of the Secret Six fled to Canada or elsewhere after Brown's capture, but Higginson never fled, despite his involvement being common knowledge. Higginson was never arrested or called to testify.[16]

In 1879, Higginson was elected to represent Cambridge's first and fifth wards in the Massachusetts House of Representatives.[21] He was re-elected in 1880.[22] He made another run for U.S. House of Representatives in 1888 as a Democrat, but was defeated by Nathaniel P. Banks.

Women's rights activism

[edit]Higginson was one of the leading male advocates of women's rights during the decade before the Civil War. In 1853, he addressed the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention in support of a petition asking that women be allowed to vote on ratification of the new constitution. Published as "Woman and Her Wishes,"[23] the address was used for many years in a women's rights tract,[24] as was an 1859 article he wrote for the Atlantic Monthly,[25] "Ought Women to Learn the Alphabet?"[26] A close friend and supporter of women's rights leader Lucy Stone, he performed the marriage ceremony of Stone and Henry Browne Blackwell in 1855 and, by sending their protest of unjust marriage laws to the press, was responsible for their "Marriage Protest" becoming a famous document.[27] Together with Stone, he compiled and published[28] The Woman's Rights Almanac for 1858,[29] which provided data such as income disparity between the sexes as well as a summary of gains made by the national movement during its first seven years.

He also compiled and published, in 1858, "Consistent Democracy. The Elective Franchise for Women. Twenty-five Testimonies of Prominent Men," brief excerpts favoring woman suffrage from the speeches or writing of such men as Wendell Phillips, Henry Ward Beecher, William Henry Channing, Horace Greeley, Gerrit Smith, and various governors, legislators, and legislative reports.[30] A member of the National Woman's Rights Central Committee since 1853 or 1854, he was one of nine activists retained in that post when that large body of state representatives was reduced in 1858.[31]

After the Civil War, Higginson was an organizer of the New England Woman Suffrage Association in 1868,[32] and of the American Woman Suffrage Association the following year. He was one of the original editors of the suffrage newspaper Woman's Journal, founded in 1870, and contributed a front-page column to it for fourteen years. As a two-year member of the Massachusetts legislature, 1880–82, he was a valuable link between suffragists and the legislature.[33]

Civil War years

[edit]

During the early part of the Civil War, Higginson was a captain in the 51st Massachusetts Infantry from November 1862 to October 1864, when he was retired because of a wound received in the preceding August. He was colonel of the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first authorized regiment recruited from freedmen for Union military service.[3] Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton required that black regiments be commanded by white officers. "We, their officers, did not go there to teach lessons, but to receive them," Higginson wrote. "There were more than a hundred men in the ranks who had voluntarily met more dangers in their escape from slavery than any of my young captains had incurred in all their lives."[34]

Higginson described his Civil War experiences in Army Life in a Black Regiment (1870),[35] He contributed to the preservation of Negro spirituals by copying dialect verses and music he heard sung around the regiment's campfires. In his book, Drawn With the Sword, historian James M. McPherson cited Higginson as an example of a white officer in a black regiment who did not share the "[p]owerful racial prejudices" of others during the time period.[36]

Religious activism

[edit]After the Civil War, Higginson became active in the Free Religious Association (FRA) and in 1870 delivered the speech The Sympathy of Religions, which was later published and circulated. The address argued that all religions shared essential truths and a common exhortation toward benevolence. Division among the faiths was ultimately artificial, he said: "Every step in the progress of each brings it nearer to all the rest. For us, the door out of superstition and sin may be called Christianity; that is an historical name only, the accident of a birthplace. But other nations find other outlets; they must pass through their own doors."[37] He pushed the FRA to tolerate even those who did not accept the liberal principles the Association espoused, asking, "Are we as large as our theory? ... Are we as ready to tolerate ... the Evangelical man as the Mohammedan?" Although his own relationship to evangelical Protestants remained strained, he saw the exclusion of any religious mindset as fundamentally dangerous to the organization.[38] Higginson spoke at the Parliament of the World's Religions in 1893 and praised the great strides that had been made in the mutual understanding of the world's great religions, describing the Parliament as the culmination of the FRA's greatest ambitions.[38]

Later years and death

[edit]

After the Civil War, he devoted most of his time to literature.[39] His writings show a deep love of nature, art and humanity. In his Common Sense About Women (1881) and his Women and Men (1888), he advocated equality of opportunity and equality of rights for men and women.[3]

In 1874, Higginson was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.[40]

In 1891, Higginson became one of the founders of the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom (SAFRF). He edited its public appeal "To the Friends of Russian Freedom". Later, in 1907 Higginson was the vice-president of the SAFRF.

In 1905, he joined with Jack London, Clarence Darrow, and Upton Sinclair to form the Intercollegiate Socialist Society.[41] Higginson was an Advisory Editor for the second attempt at the Massachusetts Magazine.

Higginson died May 9, 1911. Although his death record states that he was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he is actually buried in Cambridge Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts at the intersection of Riverview, Lawn, and Prospect paths.[42][43]

Beliefs

[edit]Higginson's deep conviction in the evils of slavery stemmed in part from his mother's influence. He greatly admired abolitionists, who, despite persecution, showed courage and commitment to the worthy cause. The writings of William Lloyd Garrison and Lydia Maria Child were particularly influential to Higginson's abolitionist enthusiasm during the early 1840s. Higginson claimed that Child's book, An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans, first convinced him to speak against slavery.[44]

Homeopathy

[edit]Higginson was a strong advocate of homeopathy. In 1863, he wrote to his wife Mary Channing Higginson: "and also Ms. Laura Towne, the homeopathic physician of the department, chief teacher and probably the most energetic person this side of civilisation [sic]: a person of splendid health and astonishing capacity.... I think she has done more for me than anyone else by prescribing homeopathic arsenic as a tonic, one powder every day on rising, and it has already, I think (3 doses) affected me."[45]

Political parties and ideology

[edit]In 1850, Higginson was the Free Soil Party candidate for Congress and lost.[46] Subsequently, he was successively a Republican, an Independent and a Democrat.[3] He described having had an interest in his early youth in Brook Farm and Fourierism.[47]

Relationship with Emily Dickinson

[edit]

Higginson is remembered as a correspondent and literary mentor to the poet Emily Dickinson.

In April 1862, Higginson published an article in the Atlantic Monthly, titled "Letter to a Young Contributor," in which he advised budding young writers to step up. Emily Dickinson, a 32-year-old woman from Amherst, Massachusetts, sent a letter to Higginson, enclosing four poems and asking, "Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?" (Letter 260) He was not – his reply included gentle "surgery" (that is, criticism) of Dickinson's raw, odd verse, questions about Dickinson's personal and literary background, and a request for more poems.

Higginson's next reply contained high praise, causing Dickinson to reply that it "gave no drunkenness" only because she had "tasted rum before"; she still, though, had "few pleasures so deep as your opinion, and if I tried to thank you, my tears would block my tongue" (Letter 265). In the same letter, Higginson warned her against publishing her poetry because of its unconventional form and style.

Gradually, Higginson became Dickinson's mentor and "preceptor," and he visited her twice, in 1870 and 1873, at her home in Amherst. Higginson never felt that he fully understood Dickinson. "The bee himself did not evade the schoolboy more than she evaded me," he wrote, "and even at this day I still stand somewhat bewildered, like the boy." ("Emily Dickinson's Letters," Atlantic Monthly, October 1891) After Dickinson's death, Higginson collaborated with Mabel Loomis Todd in publishing volumes of her poetry – heavily edited in favor of conventional punctuation, diction, and rhyme. In White Heat (Knopf, 2008), an account of Higginson's friendship with Dickinson, author Brenda Wineapple credits Higginson with more editorial sensitivity than literary historians have previously noted. Higginson's prominence within intellectual circles helped to promote Dickinson's poetry, which remained strange and startling even in its altered form.

Selected list of works

[edit]- "A Ride Through Kanzas" (1856)

- "Going to Mount Katahdin", Putnam's Monthly (September 1856), vol. VIII, pp. 242–256.[49]

- "The Story of Denmark Vesey," The Atlantic Monthly (June 1861) Denmark Vesey was a free Black pastor who was hanged in 1822 after being convicted of planning a major slave revolt that was discovered before it could be realized.

- Outdoor Papers (1863)

- The Works of Epictetus (1866), a translation based on that by Elizabeth Carter

- Eminent Women of the Age; Being Narratives of the Lives and Deeds of the Most Prominent Women of the Present Generation (1868) (Twelve biographies of women, of which Higginson wrote two: Lydia Maria Child and Margaret Fuller Ossoli)

- Malbone: an Oldport Romance (1869)

- Army Life in a Black Regiment (1870)[6]

- Atlantic Essays (1871)

- Oldport Days (1873)

- A Book of American Explorers (1877)

- Common Sense About Women (1881)

- Margaret Fuller Ossoli[6] (in American Men of Letters series, 1884)

- A Larger History of the United States of America to the Close of President Jackson's Administration (1885)

- The Monarch of Dreams (1886)

- Travellers and Outlaws (1889)

- The Afternoon Landscape (1889), poems and translations

- Life of Francis Higginson (in Makers of America, 1891)

- Concerning All of Us (1892)

- The Procession of the Flowers and Kindred Papers (1897)

- Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic (1898)

- Cheerful Yesterdays (1898)[6]

- Old Cambridge (1899)

- Contemporaries (1899). This book includes a revised version of the chapter on Lydia Maria Child in Eminent Women of the Age.

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow[6] (in American Men of Letters series, 1902)

- John Greenleaf Whittier[6] (in "English Men of Letters" series, 1902)

- A Readers History of American Literature (1903), the Lowell Institute lectures for 1903, edited by Henry W. Boynton

- "Books Unread," in The Atlantic Monthly (March 1904), reprinted in Rabinowitz, Harold, and Kaplan, Rob, eds., A Passion for Books, New York: Times Books, 1999, pp. 89–93.

- Part of a Man's Life (1905)

- Life and Times of Stephen Higginson (1907)

- Carlyle's Laugh and Other Surprises (1909)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Renehan, Edward J. Jr. (1995). The Secret Six. The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown. New York: Crown. ISBN 051759028X.

- ^ Ash, Stephen V., Firebrand of Liberty: The Story of Two Black Regiments that Changed the Course of the Civil War. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1892). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ Mary Thacher Higginson, Thomas Wentworth Higginson – The Story of His Life (Boston & New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914) pp.2–3

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilson, Susan. Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000: 119. ISBN 0-618-05013-2

- ^ Edelstein, Tilden G., Strange Enthusiasm, p. 38.

- ^ Edelstein, Tilden G., Strange Enthusiasm, p. 45.

- ^ Edelstein, Tilden G., Strange Enthusiasm, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Frederick T. McGill, Jr., Channing of Concord: A Life of William Ellery Channing II, Rutgers University Press, 1967.

- ^ Family Tree of Thomas Wentworth Higginson

- ^ Broaddus, Dorothy C. Genteel Rhetoric: Writing High Culture in Nineteenth-Century Boston. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina, 1999: 70. ISBN 1-57003-244-0.

- ^ Owen, Barbara. "History of the First Religious Society" Archived December 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, First Religious Society (Unitarian Universalist), Newburyport, MA. Accessed on August 14, 2010.

- ^ Beck, Janet Kemper. Creating the John Brown Legend: Emerson, Thoreau, Douglass, Child and Higginson in Defense of the Raid on Harpers Ferry. McFarland, April 7, 2009, p85-87

- ^ Edelstein, Tilden G., Strange Enthusiasm, pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b c Broaddus, Dorothy C. Genteel Rhetoric: Writing High Culture in Nineteenth-Century Boston. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina, 1999: 70–71. ISBN 1-57003-244-0.

- ^ Edelstein, Tilden G., Strange Enthusiasm, p. 97.

- ^ a b c d e Faust, Drew Gilpin (December 2023). "The Men Who Started the War". The Atlantic: 82–89.

- ^ Higginson, Thomas Wentworth, "A Ride Through Kanzas". Letters to the New York Tribune, 1856 (via archive.org)

- ^ Sanborn, F.B. "Thomas Wentworth Higginson (Tributes)" The Massachusetts Magazine, Vol. IV (1911), No. 3, p. 142 (via archive.org)

- ^ Manual for the Use of the General Court. Boston: Commonwealth of Massachusetts. 1880. p. 362.

- ^ Court, Massachusetts General (1881). Manual for the Use of the General Court. Boston: Commonwealth of Massachusetts. p. 378. hdl:2452/40659.

- ^ Million, Joelle, Woman's Voice, Woman's Place: Lucy Stone and the Birth of the Women's Rights Movement. Praeger, 2003. ISBN 0-275-97877-X, pp. 136–37, 173.

- ^ Wendell Phillips, Harriet Hardy Taylor Mill, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Clarina I. Howard Nichols, Theodore Parker (1854). "Woman's Rights Tracts". Boston: Robert F. Wallcut – via Internet Archive.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Women and the Alphabet, by Thomas Wentworth Higginson". www1.assumption.edu.

- ^ Meyer, 2000, pp. 266–82.

- ^ Million, 2003, p. 195.

- ^ Stone, Lucy; Susan B. Anthony Collection (Library of Congress) DLC; National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection (Library of Congress) DLC (March 6, 2019). "The Woman's Right's Almanac for 1858. Containing Facts, Statistics, Arguments, Records of Progress, and Proofs of the Need of it". Worcester, Mass.: Z. Baker & Co. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ The Woman's Rights Almanac for 1858, Containing Facts, Statistics, Arguments, Records of Progress, and Proofs of the Need of It. Worcester, Mass: Z. Baker & Co.; Boston: R. F. Walcutt. [1857]

- ^ "The Elective Franchise for Woman," National Anti-Slavery Standard, March 27, 1858, p. 3.

- ^ New York Times, May 15, 1858, p. 4.

- ^ Dubois, Ellen Carol, Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women's Movement in America, 1848–1869, Cornell University Press, (1978), p. 168.

- ^ Merk, Lois Bannister, "Massachusetts and the Woman Suffrage Movement," Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1958, Revised, 1961, pp. 16–17.

- ^ "The Color of Bravery: United States Colored Troops in the Civil War." Battlefields.org. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Higginson, Thomas Wentworth (1900). Army Life in a Black Regiment. A new edition with notes and a supplementary chapter. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (April 18, 1996). Drawn With the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War. Oxford University Press. p. 91. ISBN 9780199727834. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- ^ Higginson, Thomas Wentworth (June 2, 1870). The Sympathy of Religions. First printed in The Radical (Boston, 1871). Retrieved from Gutenberg.org, 2018-05-05.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Leigh Eric (2005). Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality from Emerson to Oprah. New York: HarperCollins, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Alexander K. McClure, ed. (1902). Famous American Statesmen & Orators. Vol. VI. New York: F. F. Lovell Publishing Company. p. 222.

- ^ "MemberListH". American Antiquarian Society.

- ^ Nichols, Richard E. (August 20, 2000). "THE MAGNIFICENT ACTIVIST The Writings of Thomas Wentworth Higginson". The New York Times.

His radicalism never dimmed; in 1906, at the age of 83, he joined with Jack London and Upton Sinclair to form the Intercollegiate Socialist Society.

- ^ Wilson, Susan. Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000: 117. ISBN 0-618-05013-2

- ^ "Massachusetts, Deaths, 1841–1915," Vol.1911/26 Death: Pg.402. State Archives, Boston.

- ^ Edelstein, Tilden G., Strange Enthusiasm, p. 51.

- ^ Christopher Looby, ed. (2000). The Complete Civil War Journal and Selected Letters of Thomas Wentworth Higginson. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-33330-2.

- ^ Edelstein, Tilden G., Strange Enthusiasm, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Higginson, Thomas W. "Views on Socialism". p. 9.

I grew up in the Brook Farm and Fourierite period and have always been interested in all tendencies in that direction.

- ^ Drew Gilpin Faust writes, "Higginson published in February 1860 the first of a series of articles in The Atlantic that he referred to as his 'Insurrection Papers.' After writing essays on 'The Maroons of Jamaica' and 'The Maroons of Surinam'—Black groups who had escaped enslavement to establish their own independent societies on the fringes of white settlement—he proceeded to publish admiring essays on Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, and Gabriel, men who had embraced violence in their efforts to overturn American slavery". Drew Gilpin Faust, "The Men Who Started the War", The Atlantic, December 2023, p. 87.

- ^ Geller, William W., "Mount Katahdin — March 1853: the Mysteries of an Ascent" (2016). Maine History Documents. 119. Page 10 identifies Higginson as the anonymous author of "Going to Katahdin", omitting "Mount", but endnote 13 on page 19 makes clear that it is the same article as "Going to Mount Katahdin".

References

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Higginson, Thomas Wentworth". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 455.

Further reading

[edit]- Bauch, Marc A. Extending the Canon: Thomas Wentworth Higginson and African-American Spirituals. Munich, Germany: Grin, 2013.

- Edelstein, Tilden G. Strange Enthusiasm: A Life of Thomas Wentworth Higginson. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968.

- Egerton, Douglas R. A Man on Fire: The Worlds of Thomas Wentworth Higginson. New York: Oxford University Press, 2024.

- Kytle, Ethan J. "An American Romantic Goes to War," The New York Times, April 15, 2011.

- Meyer, Howard N. Colonel of the Black Regiment: The Life of Thomas Wentworth Higginson. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 1967.

- Meyer, Howard N., ed. The Magnificent Activist: The Writings of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1823–1911. DaCapo Press, 2000.

- Tuttleton, James W. Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Twayne Publishers, 1978.

- Wells, Anna Mary. Dear Preceptor: The Life and Times of Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963.

- Wilson, Edmund. Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War, New York: Oxford University Press, 1962, pp. 247–256.

- Wineapple, Brenda, White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson. New York: Knopf, 2008. ISBN 978-1-4000-4401-6. plus Author Interview at the Pritzker Military Library on February 20, 2009.

Historiography

[edit]- Muccigrosso, Robert, ed. Research Guide to American Historical Biography (1988) 5:2543-46

Primary sources

[edit]- Meyer, Howard N. (ed.) The Magnificent Activist: The Writings of Thomas Wentworth Higginson (1823–1911). Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2000. ISBN 0-306-80954-0.

- Masur, Louis P. (ed.) "... the real war will never get in the books": Selections from Writers During the Civil War. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-19-506868-8. Pages 181–195 include four of Higginson's writings: (1) Letter to Louisa Higginson; (2) "The Ordeal by Battle," in The Atlantic Monthly (July 1861); (3) "Regular and Volunteer Officers," in The Atlantic Monthly (Sept. 1864); (4) "Leaves from an Officer’s Journal," in The Atlantic Monthly (Nov. 1864, Dec. 1864, Jan. 1865).

,

External links

[edit]- The Works of Epictetus by Higginson at the Internet Archive

- Negro Spirituals text with biography, images and sound files from American Studies at the University of Virginia.

- American National Biography Online:Thomas Wentworth Higginson

- Works by Thomas Wentworth Higginson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Wentworth Higginson at the Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Wentworth Higginson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Thomas Wentworth Higginson: Correspondence from the Carlton and Territa Lowenberg Collection at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries' Archives & Special Collections.

- A Ride Through Kanzas from the Antislavery Literature Project

- Biography, Works and Photos at the Worcester Writers' Project Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Thomas Wentworth Higginson Correspondence (MS Am 1162.10), Houghton Library, Harvard University

- Higginson House

- Thomas Wentworth Higginson Collection. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- Articles by Higginson in The Atlantic

- "Views on Socialism"

- 1823 births

- 1911 deaths

- 19th-century American male writers

- 19th-century American non-fiction writers

- Abolitionists from Boston

- American male non-fiction writers

- American Unitarian clergy

- Emily Dickinson

- Fourierists

- Harvard College alumni

- Harvard Divinity School alumni

- American male feminists

- American feminists

- American homeopaths

- Massachusetts Democrats

- Massachusetts Free Soilers

- Massachusetts independents

- Massachusetts Republicans

- People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War

- Secret Six

- Union army colonels

- 19th-century members of the Massachusetts General Court