Third Italian War of Independence

| Third Italian War of Independence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the wars of Italian unification and the Austro-Prussian War | |||||||||

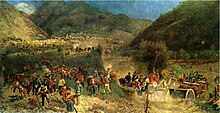

Austrian Uhlans charge Italian Bersaglieri during the Battle of Custoza. Painting by Juliusz Kossak | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by: | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Mincio Army

Total: 120,000 men Po Army

Total: 80,000 men Garibaldi's forces

Total: 20,000 men Total: 220,000 men |

South Army

Liechtenstein Army Total: 80 men Total: 130,000–190,000 men | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

11,197[1]

|

9,727[2]

| ||||||||

The Third Italian War of Independence (Italian: Terza guerra d'indipendenza italiana) was a war between the Kingdom of Italy and the Austrian Empire fought between June and August 1866. The conflict paralleled the Austro-Prussian War and resulted in Austria conceding the region of Venetia (present-day Veneto, Friuli, and the city of Mantua, the last remnant of the Quadrilatero) to France, which was later annexed by Italy after a plebiscite. Italy's acquisition of this wealthy and populous territory represented a major step in the Unification of Italy.

Background

[edit]

Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy had been proclaimed King of Italy on 17 March 1861 but did not control Venetia or the much-reduced Papal States. The situation of the Irredente, a later Italian term for part of the country under foreign domination that literally means unredeemed, was an unceasing source of tension in the domestic politics of the new kingdom and a cornerstone of its foreign policy.

The first attempt to seize Rome was orchestrated by Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1862. Confident in the king's neutrality, he set sail from Genoa to Palermo. Collecting 1,200 volunteers, he sailed from Catania and landed at Melito, Calabria, on 24 August to reach Mount Aspromonte with the intention to travel northward up the peninsula to Rome. The Piedmontese general Enrico Cialdini, however, sent a division under Colonel Pallavicino to stop the volunteer army. Garibaldi was wounded at the Battle of Aspromonte and taken prisoner, along with his men.[3]

The increasing discord between Austria and Prussia over the German Question turned into open war in 1866, which offered Italy an occasion to capture Venetia. On 8 April 1866, the Italian government signed a military alliance with Prussia[4] through the mediation of French Emperor Napoleon III.

Italian armies, led by General Alfonso Ferrero La Marmora, were to engage the Austrians on the southern front. Simultaneously, taking advantage of their perceived naval superiority, the Italians planned to threaten the Dalmatian coast and to seize Trieste.[5]

Upon the outbreak of the war, the Italian military was hampered by several factors:

- The problematic amalgamation of the armies of the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the largest components of the new Kingdom of Italy, involved disputes among the chain of command since former enemies were now serving together.[6]

- The resentment and bitter resistance in Southern Italy followed the annexation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies by Italy.

- There was an even stronger rivalry between both navies that had formed the unified Italian navy, the Regia Marina.

War

[edit]Italian invasion

[edit]Prussia opened hostilities on 16 June 1866 by attacking several German states allied with Austria. Three days later, Italy declared war on Austria and started military operations on 23 June.

The Italian forces were divided into two armies. One, under La Marmora himself, was deployed in Lombardy, west of the Mincio River, and aimed toward the powerful Quadrilatero fortress of the Austrians. The second, under Enrico Cialdini, was deployed in Romagna, south of the Po River and aimed toward Mantua and Rovigo.

La Marmora moved first through Mantua and Peschiera del Garda but was defeated at the Battle of Custoza on 24 June and retreated in disorder back across the Mincio river. Cialdini, on the other hand, did not act offensively for the first part of the war by conducting only several shows of force and failing to defeat the Austrian bridgehead at Borgoforte on the southern bank of the Po.

Following the defeat at Custoza, the Italians reorganised in preparation for a presumed Austrian counter-offensive. The Austrians took that opportunity to raid Valtellina and Val Camonica (Battle of Vezza d'Oglio).

New Italian offensive

[edit]

The course of the war, however, turned to Italy's favour by Prussian victories in Bohemia, especially the decisive Battle of Königgrätz (or Sadowa) on 3 July. The Austrians were compelled to redeploy one of their three army corps from Italy to Vienna. The remaining Austrian forces in the theatre concentrated their defences around Trentino and Isonzo.

On 5 July, the Italian government received news of a mediation effort by Napoleon III for a settlement of the situation, which would allow Austria to receive favorable conditions from Prussia and, in particular, maintain Venice. The situation was embarrassing for Italy, as its forces had been beaten back in the only battle to date. As the Austrians were redeploying more and more troops to Vienna to defend it against the Prussians, La Marmora was urged to take advantage of his force's numerical superiority, score a victory and improve the situation for Italy at the bargaining table.

On 14 July, during a council of war held in Ferrara, the new Italian war plans were decided:

- Cialdini was to lead the main army of 150,000 troops through the Venetia, and La Marmora, with roughly 70,000 men, would tie down Austrian forces in the Quadrilatero.

- The Italian Navy, commanded by Admiral Carlo di Persano was to set sail from Ancona with the objective of seizing Trieste.[5]

- Garibaldi's volunteer corps (named Cacciatori delle Alpi), reinforced by a division of regular infantry, were to advance into Trentino, with the objective of capturing its capital, Trento.

Cialdini crossed the Po on 8 July and advanced to Udine on 22 July without encountering the Austrian Army.[5] In the meantime, Garibaldi's volunteers had advanced from Brescia toward Trento during the Invasion of Trentino and won the Battle of Bezzecca on 21 July. Both advances were overshadowed, however, by the unexpected defeat of the Italian Navy at the Battle of Lissa on 20 July.

On 26 July, a mixed Italian force of bersaglieri and cavalry defeated an Austrian force guarding the crossing of the Torre River and reached what is now Romans d'Isonzo at the Battle of Versa. That marked the maximum Italian advance into Friuli. However, with the cessation of Austro-Prussian hostilities, the Austrians seemed ready to send reinforcements to Italy. Likewise, the Principality of Liechtenstein being the southern ally of Austria had sent out its army into the region west of Stilfser Joch against the volunteers.[7] On 9 August, Garibaldi was ordered in a telegraph by the Army High Command to evacuate Trentino. His reply was simply "Obbedisco" ("I shall obey") and became famous in Italy soon after.

Aftermath

[edit]

In July 1866, after the Prussian victory over Austria, the Armistice of Nikolsburg ended the hostilities between the two countries, provided that Italy obtained Venetia. The Austrians withdrew to the Isonzo River and left Venice to Italian hands.[8] France and Prussia pressured Italy to conclude an armistice on its own with Austria.[8] The Italian Prime Minister Bettino Ricasoli refused the call and insisted to obtain "natural" frontiers for Italy, including the cession of Venice and South Tyrol and that Italian interests in Istria were respected.[8] However, the Austro-Prussian armistice had strengthened Vienna's hand and Austrian admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff had taken command of the sea.[8] Eventually, the cessation of hostilities was agreed to at the Armistice of Cormons signed on 12 August, followed by the Treaty of Vienna on 3 October 1866.

The terms of the Peace of Prague included the giving of the Iron Crown of Lombardy to the Italian king and the Austrian cession of Venetia, consisting of modern Veneto, parts of Friuli and the city of Mantua. Napoleon III, who was acting as intermediary between Prussia and Austria, ceded Venetia to Italy on 19 October, as had been agreed in a secret treaty in exchange for the earlier Italian acquiescence to the French annexation of Savoy and Nice.[9]

The Treaty of Vienna confirmed the cession of the territory to Italy.[10] However, the peace treaty stated that the annexation of Venetia and Mantua would have become effective only after a plebiscite allowed the population to express its will on its annexation to the Kingdom of Italy.[11] The plebiscite was held on 21 and 22 October, and the result was an overwhelming success, with 99.9% of participants in support of joining Italy.[11][12]

Meanwhile, an uprising also occurred in Sicily, the Seven and a Half Days Revolt. The unification of Italy was completed by the Capture of Rome[13] (1870) and the annexation of Trentino, the remainder of Friuli and Trieste at the end of World War I, also called in Italy the Fourth Italian War of Independence.

See also

[edit]- First Italian War of Independence

- Second Italian War of Independence

- Austro-Prussian War

- Armistice of Cormons

- Garibaldi's Expedition against Rome

- Risorgimento

- Naval operations on Lake Garda, 1866

References

[edit]- ^ Clodfelter 2017, pp. 184.

- ^ Clodfelter 2017, p. 183.

- ^ Sons of Garibaldi in Blue and Gray: Italians in the American Civil War, Frank W. Alduino, David J. Coles, Cambria Press, New York 2007 p.36

- ^ The Austro-Prussian War: Austria's War with Prussia and Italy in 1866, Geoffrey Wawro, Cambridge University Press, 1996 p.43

- ^ a b c "Risorgimento nell'Enciclopedia Treccani". www.treccani.it. Archived from the original on 2021-10-26. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ "La Terza guerra d'indipendenza". www.150anni-lanostrastoria.it. Archived from the original on 2014-08-15. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- ^ "Sonderausstellung: '1866: Liechtenstein im Krieg – Vor 150 Jahren'". Lie:zeit (in German). 2016-05-11. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Milan Vego (23 November 2004). Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 9781135777159. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Giancarlo Giordano (2008). Cilindri e feluche. La politica estera dell'Italia dopo l'Unità. Aracne. ISBN 978-88-548-1733-3.

- ^ "(HIS, P) Treaty between Austria and Italy, (Vienna) October 3, 1866". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Full text of "A Monograph on Plebiscites: With a Collection of Official Documents"

- ^ Cronaca della nuova guerra d'Italia del 1866. 1866. pp. 573–574.

- ^ "Le guerre d'Indipendenza". Treccani, il portale del sapere. Archived from the original on 2016-04-28. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

Bibliography

[edit]- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.