Film poster

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (May 2018) |

A film poster is a poster used to promote and advertise a film primarily to persuade paying customers into a theater to see it. Studios often print several posters that vary in size and content for various domestic and international markets. They normally contain an image with text. Today's posters often feature printed likenesses of the main actors. Prior to the 1980s, illustrations instead of photos were far more common. The text on film posters usually contains the film title in large lettering and often the names of the main actors. It may also include a tagline, the name of the director, names of characters, the release date, and other pertinent details to inform prospective viewers about the film.

Film posters are often displayed inside and on the outside of movie theaters, and elsewhere on the street or in shops. The same images appear in the film exhibitor's pressbook and may also be used on websites, DVD (and historically VHS) packaging, flyers, advertisements in newspapers and magazines, and all other press related to the promotion of the film.

Film posters have been used since the earliest public exhibitions of film. They began as outside placards listing the programme of (short) films to be shown inside the hall or movie theater. By the early 1900s, they began to feature illustrations of a film scene or an array of overlaid images from several scenes. Other posters have used artistic interpretations of a scene or even the theme of the film, represented in a wide variety of artistic styles. Film posters have become increasingly coveted by art collectors in recent years due to their known relative rarity, condition, artist, and art historical significance.

History

[edit]

The first poster for a specific film, rather than a "magic lantern show", was based on an illustration by Marcellin Auzolle to promote the showing of the Lumiere Brothers film L'Arroseur arrosé at the Grand Café in Paris on December 26, 1895.[1]

Originally, film posters were produced for the exclusive use by the theaters exhibiting the film the poster was created for, and were required to be returned to the distributor after the film left the theater. In the United States, film posters were usually returned to a nationwide operation called the National Screen Service (NSS) which printed and distributed most of the film posters for the studios between 1940 and 1984. As an economy measure, the NSS regularly recycled posters that were returned, sending them back out to be used again at another theater. During this time, a film could stay in circulation for several years, and so many old film posters were badly worn before being retired into storage at an NSS warehouse (most often, they were thrown away when they were no longer needed or had become too worn to be used again). Those posters which were not returned were often thrown away by the theater owner or damaged by being outside.[2]

Beginning in the 1980s, American film studios began taking over direct production and distribution of their posters from the National Screen Service and the process of making and distributing film posters became decentralized in that country.[3] As Hollywood cinema was disseminated into foreign markets, distinct hand-painted film poster traditions arose in Poland, India, and Ghana, with depictions of posters often varying from their original Hollywood versions based on the artistry of local painters.[4][5][6]

Collecting

[edit]

After the National Screen Service ceased most of its printing and distribution operations in 1985, some of the posters which they had stored in warehouses around the United States ended up in the hands of private collectors and dealers. Today there is a thriving collectibles market in film posters, and some have become very valuable. The first auction by a major auction house solely of film posters occurred on December 11, 1990, when proceeds of a sale of 271 vintage posters run by Bruce Hershenson at Christie's totaled US$935,000.[7][8] The record price for a single poster was set on November 15, 2005, when $690,000 was paid for a poster of Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis from the Reel Poster Gallery in London.[9] Other early horror and science fiction posters are known to bring extremely high prices as well, with an example from The Mummy realizing $452,000 in a 1997 Sotheby's auction,[9] and posters from both Bride of Frankenstein and The Black Cat selling for $334,600 in Heritage Auctions, in 2007 and 2009, respectively.[10]

Occasionally, rare film posters have been found being used as insulation in attics and walls. In 2011, 33 film posters, including a Dracula Style F one-sheet (shown right), from 1930 to 1931 were discovered in an attic in Berwick, Pennsylvania and auctioned for $502,000 in March 2012 by Heritage Auctions.[11]

Over the years, old Bollywood posters, mostly from Bombay, India, especially with hand-painted art, have become collectors' items.[12][13][6] Ghanaian hand-painted movie posters from the tradition's Golden Age in the 1980s and 1990s have sold for tens of thousands of dollars and been exhibited in galleries and museums across the world.[14][15][16][17]

As a result of market demand for paper posters, some of the more popular older film posters have been reproduced either under license or illegally. Although the artwork on paper reproductions is the same as originals, reproductions can often be distinguished by size, printing quality, and paper type. Several websites on the Internet offer "authentication" tests to distinguish originals from reproductions.[18]

Original film posters distributed to theaters and other poster venues (such as bus stops) by the movie studios are never sold directly to the public. However, most modern posters are produced in large quantities and often become available for purchase by collectors indirectly through various secondary markets such as eBay. Accordingly, most modern posters are not as valuable. However, some recent posters, such as the Pulp Fiction "Lucky Strike" U.S. one-sheet poster (recalled due to a dispute with the cigarette company), are quite rare.[19]

Types

[edit]Lobby cards

[edit]

Lobby cards are similar to posters but smaller, usually 11 in × 14 in (28 cm × 36 cm), also 8 in × 10 in (20 cm × 25 cm) before 1930. Lobby cards are collectible and values depend on their age, quality, and popularity. Although typically issued in sets of eight, with each featuring a different scene from the film, some releases were, in unusual circumstances, promoted with larger (12 cards) or smaller sets (6 cards). The set for The Running Man (1963), for example, had only six cards, whereas the set for The Italian Job (1969) had twelve. Films released by major production companies experiencing financial difficulties often lacked lobby sets, such as Manhunter (1986).

A Jumbo Lobby Card is larger, 14 in × 17 in (36 cm × 43 cm) and also issued in sets. Prior to 1940 studios promoted major releases with the larger card sets. In addition to the larger size, the paper quality was better (glossy or linen). The title card displays the movie title and top stars prominently.[20]

In the United Kingdom, sets of lobby cards are known as "Front of House" cards. These, however, also refer to black-and-white press photographs, in addition to the more typical 8-by-10-inch promotional devices resembling lobby cards.

The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University holds a collection of lobby cards from silent western films that date between 1910 and 1930.[21]

Teaser poster

[edit]A teaser poster or advance poster is an early promotional film poster, containing a basic image or design without revealing too much information such as the plot, theme, and characters. The purpose is to incite awareness and generate hype for the film. A tagline may be included. There are some instances when teaser posters are issued long in advance before the film goes into production (teasers for cancelled projects are historically informative), although they are issued during the film development. Notable styles for teaser poster include:

- Bearing only a symbol associated with the film, or simply just the title.

- A main character, looking away from the screen but looking at something in the distance.

Character posters

[edit]For a film with an ensemble cast there may be a set of character posters, each featuring an individual character from the film. Usually it contains the name of the actor or the name of the character played. It may also include a tagline that reflects the quality of the character.

Sizes

[edit]Film posters come in different sizes and styles depending on the country.[22][23] The most common are listed below.[24]

United States

[edit]- One sheet, 27 inches by 40 inches (686 × 1016 mm), portrait format

- Bus stop or subway poster, 40 inches by 60 inches (1016 mm × 1524 mm), portrait format

The following sizes were in common use in the US prior to the mid-1980s, but have since been phased out of production:[citation needed]

- One sheet, 27 inches by 41 inches (686 × 1040 mm), portrait format (this size is one inch longer than the modern one sheet)

- Display (aka half-sheet), 28 inches by 22 inches (711 × 559 mm), landscape format

- Insert, size 14 inches by 36 inches (356 × 914 mm), portrait format

- Window Card, 14 inches by 22 inches (356 × 559 mm), portrait format; typically has blank space at top to accommodate promotional text for local theatre

- Two sheet, 41 inches by 54 inches (1040 × 1370 mm), either landscape format or portrait format

- Three sheet, 41 inches by 81 inches (1040 × 2060 mm), portrait format; usually assembled from two separate pieces

- 30×40, 30 inches by 40 inches (762 × 1016 mm), portrait format[25]

- 40×60, 40 inches by 60 inches (1016 × 1524 mm), portrait format[26]

- Six sheet, 81 inches by 81 inches (2060 × 2060 mm), a square format; usually assembled from four separate pieces

- Twenty four sheet, 246 inches by 108 inches (6250 × 2740 mm), landscape format often called a billboard (first displayed at the Exposition Universelle (1889))[27]

United Kingdom

[edit]- Quad (a.k.a. quad crown), size 30 inches by 40 inches (762 × 1016 mm), landscape format

- Double crown, size 20 inches by 30 inches (508 × 762 mm), portrait format

- One-sheet, size 27 inches by 40 inches (686 × 1020 mm), portrait format

- Three sheet, size 40 inches by 81 inches (1020 × 2060 mm), portrait format

Australia

[edit]- Daybill, size 13 inches by 30 inches (330 × 762 mm), portrait format (before the 1960s, Daybills were 36 inches (910 mm) long)

- One sheet, size 27 inches by 40 inches (686 × 1016 mm) portrait format

Ghana

[edit]- One-bag (locally woven flour sack, cotton canvas), size approx. 46 inches by 34 inches, portrait format[28]

- Two-bag (locally woven flour sacks, cotton canvas, stacked horizontally and sewn together), size approx. 75 inches by 44 inches, portrait format[29]

Japan

[edit]- 500 × 600 mm

France

[edit]- 120 × 160cm

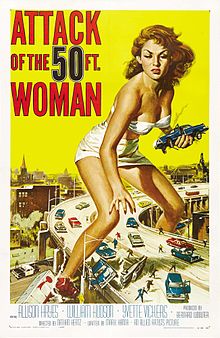

Billing block

[edit]The "billing block" is the list of names that adorn the bottom portion of the official poster (or 'one sheet', as it is called in the movie industry) of the movie".[30] A billing block can be seen at the bottom of Reynold Brown's poster from Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958), which is reproduced below. In the layout of film posters and other film advertising copy, the billing block is usually set in a highly condensed typeface (one in which the height of characters is several times the width).[31] By convention, the point size of the billing block is 25 or 35 percent of the average height of each letter in the title logo.[32] Inclusion in the credits and the billing block is generally a matter of detailed contracts between the artists and the producer. Using a condensed typeface allows the heights of the characters to meet contractual constraints while still allowing enough horizontal space to include all the required text.

Notable artists

[edit]

Normally, the artist is not identified on the film poster and, in many cases, the artist is anonymous. However, several artists have become well known because of their outstanding illustrations on film posters. Some artists, such as Drew Struzan, often sign their poster artwork and the signature is included on distributed posters.

- John Alvin

- Examples: Blade Runner, The Lion King, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

- Richard Amsel

- Examples: The Sting, Raiders of the Lost Ark

- Saul Bass

- Examples: Love in the Afternoon, Vertigo, The Shining

- Reynold Brown

- Examples: Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, Creature from the Black Lagoon, The Incredible Shrinking Man, The Time Machine

- Renato Casaro

- Examples: Conan the Barbarian, Never Say Never Again, Opera, Ghost Chase, The NeverEnding Story II: The Next Chapter

- Tom Chantrell

- Examples: Von Ryan's Express, Zulu Dawn, The Land That Time Forgot

- Jack Davis

- Examples: It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, Viva Max!, Kelly's Heroes

- Vic Fair

- Examples: Vampire Circus, Confessions of a Driving Instructor, The Man Who Fell to Earth

- Frank Frazetta

- Examples: What's New Pussycat?

- Bill Gold

- Examples: Casablanca, A Clockwork Orange, For Your Eyes Only

- Boris Grinsson

- Examples: The 400 Blows

- Karoly Grosz

- Examples: Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

- Al Hirschfeld

- Examples: The Wizard of Oz, The Sunshine Boys

- Mitchell Hooks

- Examples: Dr. No, The Sand Pebbles, El Dorado

- The Brothers Hildebrandt

- Examples: Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope ("Style B" re-release),[33] Barbarella (1979 re-release)

- Tom Jung

- Examples: Star Wars (Style A), The Empire Strikes Back (Style B), Papillon, The Lord of the Rings, Gone with the Wind (re-release)

- Mort Künstler

- Examples: The Poseidon Adventure, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974), The Hindenburg

- Frank McCarthy[34]

- Examples: The Ten Commandments, Thunderball, The Dirty Dozen, On Her Majesty's Secret Service

- Robert McGinnis[35]

- Examples: Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961), Casino Royale (1967), Diamonds Are Forever (1971)

- Noriyoshi Ohrai

- Examples: The Empire Strikes Back, Godzilla

- Bob Peak

- Examples: Our Man Flint, Camelot, Apocalypse Now, The Spy Who Loved Me, Star Trek: The Motion Picture

- Sam Peffer

- Examples: Flesh Gordon, SS Experiment Camp, Hussy

- Norman Rockwell

- Examples: The Magnificent Ambersons, The Song of Bernadette

- William Rose

- Examples: Citizen Kane, The Little Foxes, Cat People (1942)

- Enzo Sciotti

- Examples: The Beyond, Phenomena, Demons, Girlfriend from Hell, The Blood of Heroes

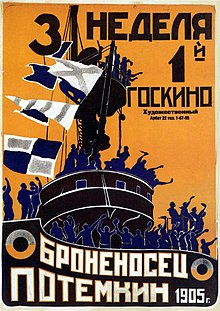

- Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg

- Examples: Man with a Movie Camera

- Drew Struzan

- Examples: Star Wars, E.T: The Extra-Terrestrial, Indiana Jones, Back to the Future, The Thing (1982), Jurassic Park, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone

- Howard Terpning

- Examples: The Guns of Navarone, Cleopatra, The Sound of Music

- Boris Vallejo

- Examples: National Lampoon's Vacation, Q, Barbarella, Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters

- Paul Wenzel

- Examples: The Parent Trap, Mary Poppins,[36][37] Pete's Dragon,[38] Dragonslayer,[39] The Fox and the Hound

Awards

[edit]The annual Clio Entertainment Awards, sponsored by The Hollywood Reporter as the Key Art Awards from 1972 to 2014 before being incorporated into the Clio Awards, include awards for best film poster in the categories of comedy, drama, action adventure, teaser, and international film. The Hollywood Reporter defines the term "key art" as "the singular, iconographic image that is the foundation upon which a movie's marketing campaign is built."[40] In 2006, the original poster for The Silence of the Lambs was named best film poster "of the past 35 years".[41]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Boyle, Bradford G. "A Theatre Owner's Guide to Movie Memorabilia", BoxOffice Magazine, November 1990, pp 14-16. (archived)

References

[edit]- ^ "The Movie Poster Begins". Filmmakeriq.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "How to Make A Mint From Movie Posters". Empire. 21 October 2013. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "National Screen Service - Demise". Learnaboutmovieposters.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "The Legacy Of Polish Posters". Smashing Magazine. 2010-01-17. Archived from the original on 2020-03-04. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- ^ Wolfe, Ernie (2000). Extreme canvas : hand-painted movie posters from Ghana (First ed.). [Los Angeles, CA]: Dilettante Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-9664272-1-1. OCLC 46897015.

- ^ a b Jerry Pinto; Sheena Sippy (2008). Bollywood Posters. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28776-7. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ Ettorre, Barbara (1991-01-11). "Entertainment Weekly Article". Archived from the original on 2014-08-09. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- ^ "eMoviePoster.com Hollywood Posters I Auction". Archived from the original on 2013-05-13. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- ^ a b "Lang movie poster fetches record". BBC News. 15 November 2005. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ Andrew Pulver (14 March 2012). "The 10 most expensive film posters – in pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ "Collecting Stories". Archived from the original on 2012-06-05. Retrieved 2012-04-14.

- ^ "Collectors can make good money with old Bollywood posters". Economic Times. Dec 18, 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-05-05. Retrieved 2013-08-20.

- ^ "100 years of Indian cinema: Top 50 hand-painted Bollywood posters". CNN-IBN. May 3, 2013. Archived from the original on May 5, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-20.

- ^ "Baptized By Beefcake: The Golden Age of Hand-Painted Movie Posters from Ghana". Poster House. 2019-04-26. Archived from the original on 2020-03-04. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- ^ Kuo, Lily (31 July 2016). "On exhibit: The hand-painted movie posters that captured kung fu's golden age in Africa". Quartz Africa. Archived from the original on 2020-03-04. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- ^ "Death-Stalking, Sleep-Walking, Barbarian Ninja Terminators: Hand-Painted Movie Posters From Ghana". Fowler Museum | Free Admission. Easy Parking. Archived from the original on 2020-03-04. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- ^ "Outrageous Supercharge Hand-Painted Movie Posters from Ghana". MASS MoCA. 19 April 2016. Archived from the original on 2020-03-04. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- ^ https://www.cinemasterpieces.com/cinearticles.htm#tell

- ^ Rosie Murray-West (5 December 2014). "Investing in film posters: which have made the most money?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12.

- ^ "Movie Poster Size Guide - Heritage Auctions". Heritage Auctions. August 30, 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-08-15. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

- ^ "The Western Silent Films Lobby Cards Collection, 1910–1930", Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, archived from the original on 2010-06-16, retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ "American Movie Poster: Sizes Types Styles". CineMasterpieces. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Vintage Movie Poster Sizes Types Kinds". CineMasterpieces. Archived from the original on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Original Film Poster Sizes, Fakes and Glossary". Movie Poster Art Gallery. Archived from the original on December 10, 2006. Retrieved December 6, 2007.

- ^ "Vintage Movie Poster Sizes". Original Film Art. Archived from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ^ "40x60 Movie Poster". Learn About Movie Posters. Archived from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ^ "Twenty Four Sheet". learn about movie posters. Archived from the original on 30 April 2004. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

The world's first 24 sheet was displayed at the Paris Exposition of 1889 and the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 by Morgan Litho.

- ^ Wolfe, III, Ernie (2000). Extreme Canvas. Los Angeles: Dilettante Press. p. 181. ISBN 0966427211.

- ^ Wolfe, III, Ernie (2012). Extreme Canvas 2: The Golden of Hand-Painted Movie Posters from Ghana. Los Angeles, California, US: Kesho Press. p. 482. ISBN 978-0615545257.

- ^ Crabb, Kelly (2005). The Movie Business: The Definitive Guide to the Legal and Financial Secrets of Getting Your Movie Made. Simon and Schuster. p. 72. ISBN 9780743264921.

- ^ "Credit Where Credit is Due". Posterwire.com. March 21, 2005. Archived from the original on 2012-06-09. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- ^ Jaramillo, Brian (March 4, 2009). "Corey Holmes watches the Watchmen". Lettercult. Archived from the original on 2012-11-10. Retrieved 2012-10-04.

- ^ "Tim Hildebrandt - Posterwire.com". Posterwire.com. 13 June 2006. Archived from the original on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- ^ "Frank McCarthy". American Art Archives. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ^ "Robert McGinnis". American Art Archives. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ^ "LOT #95132 Mary Poppins Movie Poster Preliminary Painting by Paul Wenzel (Walt Disney, 1964)". Heritage Auctions. Archived from the original on 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ "Art of the Stamp". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Archived from the original on 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ "LOT #95159 Pete's Dragon Theatrical Poster Illustration Art by Paul Wenzel (Walt Disney, 1977)". Heritage Auctions. Archived from the original on 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ "LOT #86395 Dragonslayer by Paul Wenzel (Paramount, 1981). Signed Original Acrylic International Poster Artwork (27" X 32")". Heritage Auctions. Archived from the original on 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ "Key Art:Creating a Lasting Impression". Zevendesign.com. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "Sin City' place to be at Key Art Awards". The Hollywood Reporter. 9 October 2006. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Film posters at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Film posters at Wikimedia Commons