Blood Meridian

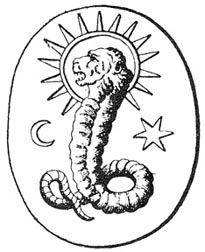

First edition cover | |

| Author | Cormac McCarthy |

|---|---|

| Language | English, Spanish |

| Genre | Western, historical novel |

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | April 1985 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hard and paperback) |

| Pages | 337 (first edition), 351 (25th anniversary edition) |

| ISBN | 0-394-54482-X (first edition, hardback) |

| OCLC | 234287599 |

| 813/.54 19 | |

| LC Class | PS3563.C337 B4 1985 |

Blood Meridian; or, The Evening Redness in the West is a 1985 anti-Western epic historical novel by American author Cormac McCarthy.[1][2] McCarthy's fifth book, it was published by Random House.

Set in the American frontier with a loose historical context, the narrative follows a fictional teenager from Tennessee referred to as "the kid", with the bulk of the text devoted to his experiences with the Glanton gang, a historical group of scalp hunters who massacred American Indians and others in the United States–Mexico borderlands from 1849 to 1850 for bounty, sadistic pleasure, and eventually out of nihilistic habit. The role of antagonist is gradually filled by Judge Holden, a physically massive, highly educated, preternaturally skilled member of the gang with pale and hairless skin who takes extreme sadistic pleasure in the destruction and domination of whatever he encounters, including children and docile animals.

Although the novel initially received lukewarm critical and commercial reception, it has since become highly acclaimed and is widely recognized as McCarthy's magnum opus and one of the greatest American novels of all time.[3] Some have labelled it the Great American Novel.[4]

Plot

[edit]The novel tells the story of a teenaged runaway referred to only as "the kid", who was born in Tennessee during the famously active Leonids meteor shower of 1833. He first meets the enormous, pale, hairless Judge Holden at a religious revival in a tent in Nacogdoches, Texas, at which Holden falsely accuses the preacher of raping children and goats, inciting the audience to attack him.

After a violent encounter with a bartender that establishes the kid as a formidable fighter, he joins a party of ill-equipped U.S. Army irregulars on a filibustering mission led by a Captain White. White's group is overwhelmed by a Comanche raiding party, and few of them survive. Arrested as a filibuster in Chihuahua, the kid is set free when his acquaintance Toadvine tells the authorities they will make useful Indian hunters. They join John Joel Glanton and his gang, among them Holden, and the bulk of the novel is devoted to detailing their activities and conversations. Though originally tasked with protecting locals from marauding Apaches, the gang devolves into the outright murder of unthreatening Indians, unprotected Mexican villages, and eventually even Mexican soldiers and anyone else who crosses their path, collecting the scalps of Indians to turn in for money whilst looting and massacring the Mexican forces.

According to the kid's new companion Ben Tobin, an "ex-priest", the Glanton gang first met Judge Holden while fleeing for their lives from a much larger Apache group. In the middle of a blasted desert, they found Holden sitting on an enormous boulder, where he seemingly was waiting for and expecting the gang. They agreed to follow his leadership, and he took them to an extinct volcano where he instructed them on how to manufacture gunpowder with the available resources, enough to give them the advantage against the Apaches. When the kid remembers seeing Holden in Nacogdoches, Tobin tells the kid that each man in the gang claims to have met the judge at some point before joining the Glanton gang.

After months of marauding and scalp hunting, the gang crosses into the Mexican Cession, where they eventually set up a systematic and brutal robbing operation at a ferry on the Colorado River at Yuma, Arizona. Local Yuma (Quechan) Indians are at first approached to help the gang wrest control of the ferry from its original owners, but Glanton's gang betrays and slaughters them and the passengers so they can plunder the ferry and frame the Indians for the attack. After a while, the Yumas vengefully attack and kill most of the gang in a second wave. The kid, Toadvine, and Tobin are among the survivors who flee into the desert, though the kid takes an arrow in the leg. The kid and Tobin head west, and come across Holden, who first negotiates, then threatens them for their gun and possessions. Holden shoots Tobin in the neck, and the wounded pair hide among bones by a desert creek. Tobin repeatedly urges the kid to fire upon Holden. The kid does so, but misses his mark.

The survivors continue their travels, ending up in San Diego, California. The kid is separated from Tobin and is subsequently imprisoned. Holden visits the kid in jail, and tells him that he has told the jailers "the truth": that the kid alone was responsible for the end of the Glanton gang. The kid is released on recognizance and seeks a doctor to treat his wound. While recovering from the effects of anesthesia, he hallucinates a visit from Holden along with a curious man who forges coins, and learns what Holden is judge of, and that "the night does not end". The kid recovers and seeks out Tobin, with no luck. He makes his way to Los Angeles, where Toadvine and another member of the Glanton gang, David Brown, were hanged for their crimes.

In 1878, the kid, now in his mid-40s and referred to as "the man", makes his way to Fort Griffin, Texas. At a saloon he meets Holden, who seems not to have aged in the intervening years. Holden calls the man "the last of the true", and the pair talk. Holden declares that the man has arrived at the saloon for "the dance" – the dance of violence, war, and bloodshed that the judge had so often praised. The man disputes Holden's ideas and, noting the performing bear at the saloon, states that "even a dumb animal can dance". When the man goes to an outhouse under another meteor shower shortly afterwards, he runs into the naked Holden, who holds him to his chest and shuts the door. Later, two men open the door to the outhouse and gaze in awe and horror at what they see. The last paragraph finds the judge back in the saloon, dancing and playing the fiddle, saying that he never sleeps and will never die.

In the epilogue, a man is augering lines of holes across the prairie, perhaps for fence posts. The man sparks a fire in each of the holes, and an assortment of wanderers trails behind him.

Characters

[edit]Major characters

[edit]- The kid: The novel's anti-heroic protagonist or pseudo-protagonist,[5] the kid is an illiterate Tennessean whose mother died in childbirth. At 14, he flees from his father to Texas. He is said to have a disposition for violence and is involved in vicious actions throughout. He takes up inherently violent professions, specifically being recruited by violent criminals including Captain White, and later by Glanton and his gang, thereby securing release from a prison in Chihuahua, Mexico. The kid takes part in many of the Glanton gang's scalp-hunting rampages, but gradually displays a moral fiber that ultimately puts him at odds with the Judge. "The kid" is later as an adult referred to as "the man".

- Judge Holden, or "the judge": A huge, pale and hairless man who often seems almost mythical or supernatural. He is a polyglot and polymath and a keen examiner and recorder of the natural world. He is extremely violent and deviant. He is said to have accompanied Glanton's gang since they found him sitting alone on a rock in the middle of the desert and he saved them from pursuing Apaches. It is hinted that he and Glanton have some manner of pact. He gradually becomes the antagonist to the kid after the dissolution of Glanton's gang, occasionally having brief reunions with the kid. Unlike the rest of the gang, Holden is socially refined and remarkably well educated; however, he perceives the world as ultimately violent, fatalistic, and liable to an endless cycle of bloody conquest, with human nature and autonomy defined by the will to violence; he asserts, ultimately, that "War is god." He is based partly on the historical character of Judge Holden.

- John Joel Glanton, or simply "Glanton": The American leader, or "captain", of a gang of scalphunters who murder Indians and Mexican civilians and military alike. His history and appearance are not clarified except that he is physically small with black hair and has a wife and child in Texas. He is a clever strategist. His last major action is to take control of a profitable Colorado River ferry, which ultimately leads to an ambush by Yuma Indians in which he is killed. He is based partly on the historical character of John Joel Glanton.

- Louis Toadvine, or simply "Toadvine": A seasoned outlaw with whom the kid brawls and then burns down a hotel. Toadvine has no ears and his forehead is branded with the letters H and T (horse thief) and F (felon). He reappears unexpectedly as a cellmate of the kid in the Chihuahua prison. From here he mendaciously negotiates the release of himself and the kid and one other inmate into Glanton's gang. Toadvine is not as depraved as some of the gang, questioning the killing of innocents, but is nonetheless a violent criminal. He is hanged in Los Angeles alongside David Brown.

- Ben Tobin, "the priest", or "the ex-priest": A member of the gang and formerly a novice of the Society of Jesus. Tobin remains deeply religious. He feels an apparently friend-like bond with the kid and abhors the judge and his philosophy. He and the Judge gradually become great spiritual enemies. He survives the Yuma massacre of Glanton's gang but is shot in the neck by the Judge. He is last seen after he arrives in San Diego with the kid and goes off on his own to look for a doctor.

Other recurring characters

[edit]- Captain White, or "the captain": An ex-professional soldier and American supremacist who believes that Mexico is a lawless nation destined to be conquered by the United States. Captain White leads a patchwork company of militants into Mexico along with the recently recruited "Kid". After weeks of travel through the harsh Mexican desert, the company is ambushed by a Comanche war party. Captain White makes his escape with a few "officers" but is ultimately caught, beheaded, and subsequently has his head "pickled".

- Bathcat, or "the vandiemenlander": Born in Wales, Bathcat went to Van Diemen's Land to hunt Aborigines. He has three fingers on his right hand. Aside from a necklace of ears, his most notable trait is a number tattooed on the inside of his forearm, suggesting that he may have been sent to the colony as a convict. He is killed by Native Americans during their travels through Pimería Alta; a fate that was foretold during his introduction.

- David Brown or simply "Brown": A member of the gang who wears a necklace of human ears - likely taken from Bathcat's corpse. He is arrested in San Diego and Glanton seems especially concerned to see him released. He brings about his own release but does not return to the gang before the Yuma massacre. He is hanged with Toadvine in Los Angeles.

- James Robert Bell, or "the idiot": A mentally challenged man who becomes affiliated with the Glanton gang after his brother, Cloyce joins. Before the brothers joined, Cloyce would keep the idiot in a cage so people could pay money to see him. He's also regularly shown chewing on his own feces. The judge takes a liking to the idiot, as he can be easy to manipulate. The judge would later have the idiot chained like a dog and make him hold his weapons. The judge later uses the idiot to try to kill both the kid and Tobin. By the end of the novel, the judge is not seen with the idiot, leaving his fate like many in the novel, unknown.

- John Jackson: "John Jackson" is a name shared by two men in Glanton's gang – one black and one white – who detest one another and whose tensions frequently rise when in each other's presence. After trying to drive the black Jackson away from a campfire with a threat of violence, "White Jackson" is decapitated. "Black Jackson" assumes an integral role in the gang. While still referred to by numerous slurs, Jackson is nonetheless treated as part of a "body" that cannot have any part killed or violated, as Judge Holden goes to great lengths to rescue him after a confrontation on a mountain pass.

Themes

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

Violence

[edit]

A major theme is the warlike nature of man. Critic Harold Bloom[6] praised Blood Meridian as one of the best 20th century American novels, "worthy of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick,"[7] but admitted that his "first two attempts to read through Blood Meridian failed, because [he] flinched from the overwhelming carnage".[8]

Caryn James of The New York Times argued that the novel's violence was a "slap in the face" to modern readers cut off from brutality.[9] Terrence Morgan thought the effect of the violence initially shocking but then waned until the reader was desensitized.[10] Billy J. Stratton of Arizona Quarterly contends that the brutality is the primary mechanism through which McCarthy challenges the "oppositional structure" of the conventional narrative of the Old West; "[R]eaders encounter characters that are often depicted as more animal than human in their behaviors, participating in a ruthless struggle for fortune and power. It is the absence of a recognizable heroic character along with the negation of the Eurocentric oppositions that McCarthy's deployment of animal imagery is meant to illuminate."[11]

James D. Lilley argues that many critics struggle with the fact that McCarthy does not use violence for "jury-rigged, symbolic plot resolutions ... In McCarthy's work, violence tends to be just that; it is not a sign or symbol of something else."[12] In her aforementioned review, Caryn James noted that McCarthy depicts characters of all backgrounds as evil, in contrast to contemporary "revisionist theories that make white men the villains and Indians the victims."[9]

Epigraphs

[edit]

"You can find meanness in the least of creatures, but when God made man the Devil was at his elbow. A creature that can do anything"

Three epigraphs open the book: quotations from French writer Paul Valéry, from German Christian mystic Jakob Böhme, and a 1982 news clipping from the Yuma Sun reporting the claim of members of an Ethiopian archeological excavation that a fossilized skull three hundred millennia old seemed to have been scalped. Regarding the meaning of the epigraphs, David H. Evans writes that

[t]he taking of scalps, as McCarthy's third epigraph suggests, enjoys a profound antiquity, one coterminous with, perhaps, the beginnings of the species Homo sapiens.[13]

Ending

[edit]The narrative closes with ambiguity pertaining to the final state of the kid, or the man. Since the book portrays violence in explicit detail, this allusive portrayal has caused comment. Given Judge Holden's history and other details in the text, he presumably rapes the man before killing him.[14] Alternatively, perhaps the point is that readers can never know.[15]

Religion

[edit]

Hell

[edit]David Vann argues that the setting of the American southwest which the Gang traverses is representative of hell. Vann claims that the Judge's kicking of a head is an allusion to Dante's similar action in the Inferno.[16]

Gnosticism

[edit]The second of the three epigraphs which introduce the novel, taken from the Christian theosophist Jakob Böhme, has incited varied discussion. The quote from Boehme is:

It is not to be thought that the life of darkness is sunk in misery and lost as if in sorrowing. There is no sorrowing. For sorrow is a thing that is swallowed up in death, and death and dying are the very life of the darkness.[17]

No specific conclusions have been reached about its interpretation nor relevance to the novel.[citation needed] Critics agree that there are Gnostic elements in Blood Meridian, but they disagree on the precise meaning and implication of those elements.

Leo Daugherty argues that "Gnostic thought is central to Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian", (Daugherty, 122) specifically the Persian-Zoroastrian-Manichean branch of Gnosticism. He describes the novel as a "rare coupling of Gnostic 'ideology' with the 'affect' of Hellenic tragedy by means of depicting how power works in the making and erasing of culture, and of what the human condition amounts to when a person opposes that power and thence gets introduced to fate."[18] Daugherty sees Holden as an archon and the kid as a "failed pneuma."[citation needed] He says that the kid feels a "spark of the alien divine."[19]

Daugherty further contends that the violence of the novel can best be understood through a Gnostic lens. "Evil" as defined by the Gnostics was a far larger, more pervasive presence in human life than the rather tame and "domesticated" Satan of Christianity. As Daugherty writes, "For [Gnostics], evil was simply everything that is, with the exception of bits of spirit imprisoned here. And what they saw is what we see in the world of Blood Meridian."[20]

However, Barcley Owens argues that while there are undoubtedly Gnostic qualities to the novel, Daugherty's arguments are "ultimately unsuccessful,"[21] because Daugherty fails to adequately address the pervasive violence and because he overstates the kid's goodness.[citation needed]

Theodicy

[edit]Douglas Canfield asserts that theodicy is the central theme of Blood Meridian. James Wood took a similar position, recognizing as a recurrent theme in the novel the issue of the general justification of metaphysical goodness in the presence of evil.[22] Chris Dacus expressed his preference for discussing the theme of theodicy in its eschatological terms in comparison to the theological scene of the last judgment.[1] This preference for reading theodicy as an eschatological theme was further affirmed by Harold Bloom in his recurrent phrase of referring to the novel as "The Authentic Apocalyptic Novel."[23]

Writing

[edit]

McCarthy began writing Blood Meridian in the mid-1970s.[24] In a letter sent around 1979 he said that he had not touched Blood Meridian in six months out of frustration.[5] Nonetheless, significant parts of the final book were written in one go, "including the astonishing 'legion of horribles' passage".[5]

A legion of horribles, hundreds in number, half naked or clad in costumes attic or biblical or wardrobed out of a fevered dream with the skins of animals and silk finery [...].

McCarthy worked on the novel while living on the money he received from his MacArthur Fellows grant in 1981. It was his first attempt at a western and his first novel set in the Southwestern United States, a change from the Appalachian settings of his earlier work.[5]

In 1974, McCarthy moved from his native Tennessee to El Paso, Texas, to immerse himself in the culture and geography of the American Southwest. He taught himself Spanish, which many of the characters of Blood Meridian speak.[5] McCarthy conducted considerable research to write the book. Critics have repeatedly demonstrated that even brief and seemingly inconsequential passages of Blood Meridian rely on historical evidence. The book has been described as "as close to history as novels generally get".[25]

The Glanton gang segments are based on Samuel Chamberlain's account of the group in his memoir My Confession: The Recollections of a Rogue. Chamberlain rode with John Joel Glanton and his company between 1849 and 1850. Judge Holden is described in Chamberlain's account but is otherwise unknown. Chamberlain writes:

The second in command, now left in charge of the camp, was a man of gigantic size who rejoiced in the name of Holden, called Judge Holden of Texas. Who or what he was no one knew, but a cooler-more blooded villain never went unhung. He stood six foot six in his moccasins, had a large, fleshy frame, a dull, tallow-colored face destitute of hair and all expression, always cool and collected. But when a quarrel took place and blood shed, his hog-like eyes would gleam with a sullen ferocity worthy of the countenance of a fiend ... Terrible stories were circulated in camp of horrid crimes committed by him when bearing another name in the Cherokee nation in Texas. And before we left Fronteras, a little girl of ten years was found in the chaparral foully violated and murdered. The mark of a huge hand on her little throat pointed out him as the ravisher as no other man had such a hand. But though all suspected, no one charged him with the crime. He was by far the best educated man in northern Mexico.[26]

McCarthy's judge was added to his manuscript in the late 1970s, a "grotesque patchwork of up-river Kurtz and Milton's Satan" and Chamberlain's account.[5]

McCarthy physically retraced the Glanton Gang's path through Mexico multiple times, and noted topography and fauna.[5] He studied such topics as homemade gunpowder to accurately depict the judge's creation from volcanic rock.

Style

[edit]McCarthy's writing style involves many unusual or archaic words, dialogue in Spanish, no quotation marks for dialogue, and no apostrophes to signal most contractions.[citation needed] McCarthy told Oprah Winfrey in an interview that he preferred "simple declarative sentences" and that he used capital letters, periods, an occasional comma, a colon for setting off a list, but never semicolons.[27] He believed there was no reason to "blot the page up with weird little marks".[28] The New York Times described McCarthy's prose in Blood Meridian as "Faulknerian".[29] Describing events of extreme violence, McCarthy's prose is sparse yet expansive, with an often biblical quality and frequent religious references.[citation needed]

Reception and reevaluation

[edit]Blood Meridian initially received little recognition, but has since been recognized as a masterpiece and one of the greatest works of American literature. Some have called it the Great American Novel.[4] American literary critic Harold Bloom praised Blood Meridian as one of the 20th century's finest novels.[30] Aleksandar Hemon has called it "possibly the greatest American novel of the past 25 years".[31] David Foster Wallace named it one of the five most underappreciated American novels since 1960[32] and "[p]robably the most horrifying book of this [20th] century, at least [in] fiction."[33]

Time magazine included Blood Meridian in its "Time 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005".[34] In 2010 The New York Times conducted a poll of writers and critics regarding the most important works in American fiction from the previous 25 years, and Blood Meridian was a runner-up.[35]

Literary significance

[edit]There has been no consensus in the interpretation of the novel. Americanist Dana Phillips said that the work "seems designed to elude interpretation".[36] One scholar has described Blood Meridian as:

Lyrical at times, at others simply archaic and recondite, at still others barely literate: the dissociative style of Blood Meridian defies accommodation to conventional assumptions. And that's the point.[25]

Nonetheless, academics and critics have suggested that Blood Meridian is nihilistic or strongly moral, a satire of the western genre or a savage indictment of Manifest Destiny. Harold Bloom called it "the ultimate western". J. Douglas Canfield described it as "a grotesque Bildungsroman in which we are denied access to the protagonist's consciousness almost entirely".[37] Richard Selzer declared that McCarthy "is a genius – also probably somewhat insane."[38] Critic Steven Shaviro wrote:

In the entire range of American literature, only Moby-Dick bears comparison to Blood Meridian. Both are epic in scope, cosmically resonant, obsessed with open space and with language, exploring vast uncharted distances with a fanatically patient minuteness. Both manifest a sublime visionary power that is matched only by still more ferocious irony. Both savagely explode the American dream of manifest destiny of racial domination and endless imperial expansion. But if anything, McCarthy writes with a yet more terrible clarity than does Melville.

— Steven Shaviro, "A Reading of Blood Meridian"[39]

Attempted film adaptations

[edit]

Since the novel's release many have noted its cinematic potential. The New York Times' 1985 review noted that the novel depicted "scenes that might have come off a movie screen".[29] There have been attempts to create a motion picture adaptation of Blood Meridian, but all have failed during the development or pre-production stages. A common perception is that the story is "unfilmable" due to its unrelenting violence and dark tone.[40] In an interview with The Wall Street Journal in 2009 McCarthy denied this notion, with his perspective being that it would be "very difficult to do and would require someone with a bountiful imagination and a lot of balls. But the payoff could be extraordinary."[41]

Screenwriter Steve Tesich first adapted Blood Meridian into a screenplay in 1995. In the late 1990s, Tommy Lee Jones acquired the film adaptation rights to the story and subsequently rewrote Tesich's screenplay with the idea of directing and playing a role in it.[42] The production could not move forward due to film studios avoiding the project's overall violence.[43]

Following the end of production for Kingdom of Heaven in 2004, screenwriter William Monahan and director Ridley Scott entered discussions with producer Scott Rudin for adapting Blood Meridian with Paramount Pictures financing.[44] In a 2008 interview with Eclipse Magazine Scott confirmed that the screenplay had been written, but that the extensive violence was proving to be a challenge for film standards.[45] This later led to Scott and Monahan leaving the project, resulting in another abandoned adaptation.[46]

By early 2011, James Franco was considering adapting Blood Meridian, along with a number of other William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy novels. After being persuaded by Andrew Dominik to adapt the novel, Franco shot 25 minutes of test footage starring Scott Glenn, Mark Pellegrino, Luke Perry, and Dave Franco. For undisclosed reasons, Rudin denied further production of the film.[43] On May 5, 2016, Variety revealed that Franco was negotiating with Rudin to write and direct an adaptation to be brought to the Marché du Film, starring Russell Crowe, Tye Sheridan, and Vincent D'Onofrio. However, it was reported later that day that the project dissolved due to issues with the film rights.[47]

In 2023, Deadline reported that New Regency is adapting Blood Meridian as a feature film. John Hillcoat, who previously directed an adaptation of McCarthy's novel The Road, is set to direct. Alongside his son John Francis, McCarthy was set to serve as an executive producer on the film;[48] he will retain a posthumous credit following his death on June 13, 2023.[49] John Logan was later announced to be adapting the story.[50]

References

[edit]- ^ Kollin, Susan (2001). "Genre and the Geographies of Violence: Cormac McCarthy and the Contemporary Western". Contemporary Literature. 42 (3). University of Wisconsin Press: 557–88. doi:10.2307/1208996. JSTOR 1208996.

- ^ Hage, Erik. Cormac McCarthy: A Literary Companion. North Carolina: 2010. p. 45

- ^ "Harold Bloom on Blood Meridian". The A.V. Club. 15 June 2009. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Dalrymple, William. "Blood Meridian is the Great American Novel". Reader's Digest. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

McCarthy's descriptive powers make him the best prose stylist working today, and this book the Great American Novel.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shannon, Noah Gallagher (6 October 2012). "Cormac McCarthy's Surprisingly Emotional First Drafts". Slate.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (2001). How to Read and Why. New York City: Simon and Schuster. p. 254. ISBN 978-0684859071.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (September 24, 2003). Dumbing down American readers.

{{cite book}}:|newspaper=ignored (help) - ^ Bloom, H. (2010), Introduction, in McCarthy, C. Blood Meridian, Modern Library, Random House, NY, 9780679641049, p. vii

- ^ a b James, Caryn (28 April 1985). "'Blood Meridian,' by Cormac McCarthy". The New York Times.

- ^ Owens 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Stratton, Billy J. (Autumn 2011). "'el brujo es un coyote': Taxonomies of Trauma in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian". Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory. 67 (3). Tucson, Arizona: Johns Hopkins University Press on behalf of University of Arizona: 151–172. doi:10.1353/arq.2011.0020. S2CID 161619604.

- ^ Lilley 2014, p. 19.

- ^ Evans, David H. (Winter 2013). "True West and Lying Marks: 'The Englishman's Boy, Blood Meridian,' and the Paradox of the Revisionist Western". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 55 (4). Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press: 406–433. doi:10.7560/TSLL55403. S2CID 161028723.

- ^ Shaw 1997, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Peter J. Kitson (ed.). "The Year's Work in English Studies Volume 78 (1997)", Kitson, p. 809.

- ^ Vann, David (November 13, 2008). "American inferno". The Guardian. London. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ Mundik, Petra (May 15, 2016). A Bloody and Barbarous God: The Metaphysics of Cormac McCarthy. University of New Mexico Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8263-5671-0. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ Daugherty 1992, p. 129.

- ^ Daugherty, Leo. “Gravers False and True: Blood Meridian as Gnostic Tragedy.” Perspectives on Cormac McCarthy. Ed. Edwin T. Arnold and Dianne C. Luce. University Press of Mississippi: Jackson, 1993. 157-172.

- ^ Daugherty 1992, p. 124.

- ^ Owens 2000, p. 12.

- ^ Wood, James (July 25, 2005). "Red Planet: The sanguinary sublime of Cormac McCarthy". The New Yorker. New York. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ "Interview with Harold Bloom". November 28, 2000. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ Shannon, Noah (2012-10-05). "Cormac McCarthy Cuts to the Bone". Slate Book Review, 5 October 2012.

- ^ a b Mitchell, L. C. (2015) ‘A Book "Made Out of Books": The Humanizing Violence of Style in "Blood Meridian"’, Texas studies in literature and language, 57(3), pp. 259–281. doi: 10.7560/TSLL57301.

- ^ McNabb, Max (16 January 2019). "The Monster Who was Real: Judge Holden of Texas, Scalp-hunting Giant". Texas Hill Country.

- ^ Lincoln, Kenneth (2009). Cormac McCarthy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-230-61967-8.

- ^ Crystal, David (2015). Making a Point: The Pernickity Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Book. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-78125-350-2.

- ^ a b James, Caryn (April 28, 1985). "'Blood Meridian,' by Cormac McCarthy". The New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ "Bloom on "Blood Meridian"". Archived from the original on 2006-03-24.

- ^ Books, Five (February 9, 2010). "Man's Inhumanity to Man". Five Books. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ Wallace, David Foster. "Overlooked". Salon. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- ^ "Gus Van Sant Interviews David Foster Wallace". Archived from the original on 2014-05-11. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- ^ "All Time 100 Novels". Time. 2005-10-16. Archived from the original on October 19, 2005. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "If You Liked My Book, You'll Love These". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023.

- ^ Lilley 2014, p. 9.

- ^ Canfield 2001, p. 37.

- ^ Owens 2000, p. 9.

- ^ Shaviro 1992, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Mosley, Matthew (2023-04-04). "Hollywood Keeps Trying to Adapt Cormac McCarthy's "Unfilmable" Novel". Collider. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- ^ John, Jurgensen (November 20, 2009). "Cormac McCarthy". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ Balchack, Brian (May 9, 2014). "William Monahan to adapt Blood Meridian". MovieWeb. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ a b Franco, James (July 6, 2014). "Adapting 'Blood Meridian'". Vice. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ Stax (May 10, 2004). "Ridley Scott Onboard Blood Meridian?". IGN. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ Essman, Scott (June 3, 2008). "Interview: The great Ridley Scott Speaks with Eclipse by Scott Essman". Eclipse Magazine. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ Horn, John (August 17, 2008). "Cormac McCarthy's 'The Road' comes to the screen". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (May 5, 2016). "Russell Crowe in Talks to Star in James Franco-Directed 'Blood Meridian'". Variety. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (April 28, 2023). "New Regency Adapting Cormac McCarthy's 'Blood Meridian' Into Feature Film With John Hillcoat Directing". Deadline. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "Cormac McCarthy, author of The Road, dies aged 89". BBC News. June 13, 2023. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

- ^ Stephan, Katcy (April 24, 2024). "John Logan Tapped to Write Film Adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's 'Blood Meridian'". Variety. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Canfield, J. Douglas (2001). Mavericks on the Border: Early Southwest in Historical fiction and Film. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2180-9.

- Daugherty, Leo (1992). "Gravers False and True: Blood Meridian as Gnostic Tragedy". Southern Quarterly. 30 (4): 122–133.

- Lilley, James D. (2014). "History and the Ugly Facts of Blood Meridian". Cormac McCarthy: New Directions. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-2767-3.

- Owens, Barcley (2000). Cormac McCarthy's Western Novels. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1928-5.

- Schneider, Christoph (2009). "Pastorale Hoffnungslosigkeit. Cormac McCarthy und das Böse". In Borissova, Natalia; Frank, Susi K.; Kraft, Andreas (eds.). Zwischen Apokalypse und Alltag. Kriegsnarrative des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts. Bielefeld. pp. 171–200.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shaviro, Steven (1992). "A Reading of Blood Meridian". Southern Quarterly. 30 (4).

- Shaw, Patrick W. (1997). "The Kid's Fate, the Judge's Guilt: Ramifications of Closure in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian". Southern Literary Journal: 102–119.

- Stratton, Billy J. (2011). "'el brujo es un coyote': Taxonomies of Trauma in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian". Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory. 67 (3): 151–172. doi:10.1353/arq.2011.0020. S2CID 161619604.

Further reading

[edit]- Sepich, John (2008). Notes on Blood Meridian. Southwestern Writers Collection Series. Foreword by Edwin T. Arnold (Revised and Expanded ed.). University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71821-0. Archived from the original on 2011-04-19. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

External links

[edit]- 1985 American novels

- Novels by Cormac McCarthy

- American bildungsromans

- American historical novels

- American philosophical novels

- Western (genre) novels

- Novels set in Texas

- Novels set in Mexico

- Novels set in Arizona

- Novels set in California

- Novels set in deserts

- Fiction set in 1849

- Fiction set in 1850

- Fiction set in 1878

- Fiction about immortality

- Novels set in the 1840s

- Novels set in the 1850s

- Novels set in the 1870s

- Revisionist Westerns

- Epic novels