Vegetarian Society

Vegetarian Society of the United Kingdom | |

| |

Interior of Northwood Villa, where the Society was founded in 1847 | |

| Abbreviation | VSUK |

|---|---|

| Formation | 30 September 1847 |

| Founded at | Ramsgate, Kent, England |

| Merger of |

|

| Type | Charity |

| Registration no. | 259358 |

| Legal status | Charity |

| Focus | Vegetarianism |

| Headquarters | Manchester, England |

Region | United Kingdom |

| Membership | 6,500[1] (2023) |

CEO | Richard McIlwain[2] |

Main organ | The Pod |

| Revenue | £1,081,545[3] (2023) |

| Expenses | £1,426,451[3] (2023) |

| Staff | 18[3] (2023) |

| Website | vegsoc |

The Vegetarian Society of the United Kingdom (VSUK) is a British registered charity. It campaigns for dietary changes, licenses Vegetarian Society Approved trademarks for vegetarian and vegan products, runs a cookery school and lottery, and organises National Vegetarian Week in the UK.

In the 19th century, various groups in Britain promoted meat-free diets, leading to the formation of the Vegetarian Society in 1847, which later split into the Manchester and London Vegetarian Societies in 1888 before reuniting in 1969, registering as a charity, and continued advocating for vegetarianism through public education and influencing food producers.

Focus areas and activities

[edit]| Vegetarian Society Approved | |

|---|---|

| Effective region | Global |

| Effective since |

|

| Website | vegsoc.org/trademarks |

The Vegetarian Society campaigns to encourage dietary changes, reduce meat consumption, and assist policymakers in developing a more compassionate food system.[1]

In 1969, the Society introduced the Vegetarian Society Approved trademark.[4] It launched a Vegetarian Society Approved vegan trademark in 2017.[5] The trademarks are licensed to companies to display on products which contain only vegetarian or vegan ingredients, and also that nothing non-vegetarian or non-vegan was used during the production process. These trademarks can be seen on products in shops and supermarkets and also on dishes in restaurants.[6] In 2022 McDonald's launched their McPlant burger across the UK which is accredited with the Vegetarian Society Approved vegan trademark.[7]

National Vegetarian Week is the charity's flagship event.[8] It started in 1992 as a single day and was expanded into a full week.[9]

The Vegetarian Society Cookery School runs leisure classes in vegetarian and vegan cooking. It collaborates with various charities and community groups to provide tailored cookery courses. The school offers training for professional chefs and individuals seeking new careers in the food sector through its Professional Chef's Diploma program.[10]

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]In the 19th century, a number of groups in Britain actively promoted and followed meat-free diets. Key groups involved in the formation of the Vegetarian Society were members of the Bible Christian Church, supporters of the Concordium, and readers of the Truth-Tester journal.[11]

Bible Christian Church

[edit]The Bible Christian Church was founded in 1809 in Salford by Reverend William Cowherd after a split from the Swedenborgians. One distinctive feature of the Bible Christians was a belief in a meat-free diet, or ovo-lacto vegetarianism, as a form of temperance.[12][13]

Concordium (Alcott House)

[edit]The Concordium was a boarding school near London on Ham Common, Richmond, Surrey, which opened in 1838. Pupils at the school followed a diet completely free of animal products, known today as a vegan diet. The Concordium was also called Alcott House, in honour of American education and food reform advocate Amos Bronson Alcott.[11]

Truth-Tester and Physiological Conference, 1847

[edit]The Truth-Tester was a journal which published material supporting the temperance movement. In 1846 the editorship was taken over by William Horsell, operator of the Northwood Villa Hydropathic Institute in Ramsgate. Horsell gradually steered the Truth-Tester towards promotion of the "Vegetable Diet". In early 1847 a letter to the Truth-Tester proposed the formation of a Vegetarian Society. In response to this letter, William Oldham held what he called a "physiological conference" in July 1847 at the Concordium. Up to 130 attended, including Bible Christian James Simpson, who presented a speech. The conference passed a number of resolutions, including a resolution to reconvene at the end of September.[11]

Ramsgate Conference, 1847

[edit]

On 30 September 1847 the meeting which had been planned at the Physiological Conference took place at Northwood Villa Hydropathic Institute in Ramsgate.[14] Joseph Brotherton, MP for Salford, and a Bible Christian chaired. James Simpson was elected president of the society, Concordist William Oldham elected treasurer, and Truth-Tester editor William Horsell elected secretary.[15] The name "Vegetarian Society" was chosen for the new organisation by a unanimous vote.[14]

After Ramsgate

[edit]The Vegetarian Society's first full public meeting was held in Manchester the following year, attracting 265 members aged 14 to 76, with 232 attending the dinner following the meeting.[14] In 1853 it already had 889 members.[16]

In 1849, London's vegetarians gathered and resolved to enhance the spread of vegetarianism in the capital. Consequently, in September 1849, they launched The Vegetarian Messenger, a journal that distributed almost 5,000 copies monthly at a cost of one penny each.[14] The society made available publications on the topic sometimes accompanied by lectures.[17]

Following the deaths of Simpson, Brotherton, and their American colleague Alcott, the vegetarian movement experienced a sharp decline. Membership numbers fell significantly during the 1860s and 1870s, with only 125 members remaining by 1870.[18]

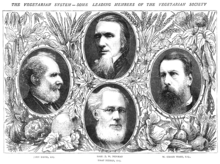

London Food Reform Society

[edit]

The London Food Reform Society, founded in 1875 with the help of Martin Nunn, an advocate of cooperation and industrial reform, held free bi-monthly lectures and debates at Franklin Hall, attracting increasing audiences due to support from eager young men and notable food reformers.[19]

The Society's Food Reform Magazine subtly criticised the Vegetarian Society in Manchester for not being supportive enough. While Manchester believed its organisation was sufficient, London vegetarians, often new converts, disagreed and considered relocating the national offices to London. Debates in 1882 and 1883 on expanding to a national scope faced criticism due to potential hostility and funding issues. The Society briefly renamed itself the National Food Reform Society until October 1885 when the Vegetarian Society paid its debts and made it an auxiliary in London. This led to the loss of the Food Reform Society's subscription list interest, office closure, and establishment of an independent auxiliary.[19] W. J. Monk was its president.[20] The Vegetarian Society's London Auxiliary became an independent body under the name London Vegetarian Society in 1888.[21]

Dietary policy debates and growth

[edit]

From its founding, the Society was primarily influenced by members of the Bible Christian Church in Salford, who advocated for the inclusion of eggs, dairy products, and honey in their diet based on biblical teachings. They had no plans to reduce the consumption of these animal products. In contrast, Henry Stephens Salt argued in his 1885 work A Plea for Vegetarianism that the main goal of vegetarians should be to abolish flesh-meat while acknowledging that dairy and eggs were also unnecessary and could be eliminated in the future. Salt emphasised rejecting unhealthy, expensive, and unwholesome food rather than just animal products.[22]

Francis William Newman served as president of the Vegetarian Society from 1873 to 1883.[23] He made an associate membership possible for people who were not completely vegetarian, such as those who ate chicken or fish.[18] Newman was critical of raw food vegetarianism which he rejected as fanatical.[18] He believed that abstinence from meat, fish and fowl should be the only thing the Society advocates and that it should not be associated with other reform ideas.[18][24] He was also against the abandonment of salt and seasonings.[18]

Under Newman's presidency the Society flourished as income, associates and members increased.[24] From 1875 to 1896 membership for the Society rose to 2,159 and associate membership 1,785.[18] Around 1897 its membership was about 5,000.[25] In regard to the associate membership, Newman commented:[24]

It occurs to me to ask whether certain grades of profession might not be allowed within our Society, which would give to it far greater material support, enable it to circulate its literature, and at the same time retain the instructive spectacle of a select band of stricter feeders... Yet, as our Society is at present (1871) constituted, all those friendly are shut out... But if they entered as Associates in the lowest grade... they might be drawn on gradually, and would swell our funds, without which we can do nothing.

Manchester and London Vegetarian Societies

[edit]If anybody said that I should die if I did not take beef tea or mutton, even on medical advice, I would prefer death. That is the basis of my vegetarianism.

Relations between the Society in Manchester and the London branch were strained due to differing definitions of vegetarianism[23] and conflicts over required approval of "advanced" literature by the Society.[19] In 1888, the London branch split, forming the London Vegetarian Society (LVS),[18] also known as the London Vegetarian Association.[27] After this, the Vegetarian Society was often referred to as the Manchester Vegetarian Society (MVS).[23]

The first President of the LVS was raw food advocate Arnold Hills, and other members included Thomas Allinson and Mahatma Gandhi.[23] Members of the LVS were considered more radical than the MVS.[18]

The newly independent society's ambitions were laid out in its journal, The Vegetarian, funded by Arnold Hills. Despite challenges, optimism prevailed with plans for a Charing Cross Vegetarian Hotel and Restaurant. Several branches existed, attracting new members in Oxford, Nottingham, Brighton, Guildford, and Reading. In 1889, the LVS and Vegetarian offices moved to the Congregational Memorial Hall, becoming a hub for reform activities.[19] The movement's growth led to specialist societies for children, athletes, and others, with vegetarian restaurants serving as meeting places. In 1889, the LVS created a national Vegetarian Federal Union, despite controversy from the MVS. By 1901, 21 societies had been established, coordinated from 1895 by the LVS.[19]

20th century

[edit]

In 1907, James Christopher Street, J. Stenson Hooker, Ernest Nyssens and Eustace Miles were speakers at the 60th Anniversary of the Vegetarian Society in Manchester.[28] In 1920, the MVS hosted a summer school at Arnold House, Llanddulas, attracting around 70 attendees each week. Both societies organised holidays and outings for vegetarians, with the MVS's May meetings remaining popular annual events well after World War II.[29]

World War I was a challenging period for vegetarians; no allowance was made for vegetarians in the armed forces.[29]

In World War II, the Committee of Vegetarian Interests was established, comprising members from the two Vegetarian Societies, health food manufacturers, and retailers, to negotiate with the Ministry of Food.[29] During WWII, the blockade of the UK lead to food shortages, and the government became intimately involved in the diet of the civilian population. Food was rationed, with ration coupons becoming a second currency needed to buy all rationed goods.[30] Vegetarians were well-catered for. Anyone who registered as vegetarian with their local Food Office got special ration books. These had no meat ration; instead, there were more ration coupons for cheese, eggs, and nuts. There were about 100,000 people officially registered as vegetarians in the UK during WWII.[30]

Meat rations during the war were very small (in order to increase the food supply; see trophic level). Many meals had to be vegetarian, and the government promoted vegetarian recipes. The whole population ate much more cereals and vegetables, and much less meat. Many retained wartime eating habits after the war. There was also great public interest in nutrition and diets, and the effects of eating less meat.[30]

The 1950s saw a significant rise in the popularity of vegetarian cuisine. Walter Fleiss, who owned the well-known Vega restaurant near Leicester Square in London, successfully lobbied for the inclusion of a vegetarian category in the Salon Culinaire Food Competition. Sponsored by the Society, this event and subsequent ones brought vegetarianism into mainstream awareness.[29]

Founding of The Vegan Society

[edit]The inclusion of eggs and dairy in a vegetarian diet was a long-standing topic of debate within the Society. In 1944, Donald Watson, a member of the LVS, suggested creating a separate group for those adhering to a dairy- and egg-free diet. This led to the establishment of The Vegan Society.[31]

Reunification

[edit]In the 1950s and 1960s, former rivalries were put aside as the MVS and LVS started working together, with many calling for unification. In 1958, their magazines combined to become The British Vegetarian.[29] They reunited in 1969, forming the Vegetarian Society of the United Kingdom.[23] Their headquarters were established at Parkdale, Altrincham, Greater Manchester.[31] The organisation became a registered charity in September of that year.[1]

Advocacy efforts

[edit]In the 1950s, Frank Wokes founded the Vegetarian Nutritional Research Centre in Watford, working closely with the Society to promote research on vegetarian nutrition and health. The centre was eventually absorbed by the Society, leading to extensive research efforts, with results published in major journals, magazines, and newspapers.[29]

In 1969, the Society introduced its seedling logo.[32] In 1986, they introduced a scheme allowing manufacturers to use their logo on foods that met their strict vegetarian guidelines.[29] Their accreditation criteria states that the food must be: free from animal flesh, slaughterhouse byproducts, and cross-contamination with non-vegetarian products; not tested on animals; only GMO-free and free-range eggs (with specific humane standards) are used.[32] This initiative led to the widespread use of vegetarian symbols on food packaging.[29]

In 1982, The Vegetarian Society launched The Cordon Vert Cookery School, a leading vegetarian culinary academy. In 1991, the Society hosted the first National Vegetarian Week, an event that has been held nearly every year since, gaining significant media attention and attracting many to vegetarianism. Vegfest, introduced in 1997, is an annual celebration in central Manchester, drawing thousands of attendees.[29]

In 1995, the Society produced the documentary Devour the Earth, written by Tony Wardle and narrated by Paul McCartney.[33] McCartney became a patron of the society in the same year.[34]

21st century

[edit]The Vegetarian Society Awards were inaugurated in 2001 to acknowledge businesses and services that cater to the UK's population of vegetarians. The first ceremony took place at the Grosvenor House Hotel in London, with later events at The Waldorf Hotel and The Magic Circle headquarters. These early events, open to members and the public, included fundraising activities such as celebrity auctions and raffles, with prizes donated by vegetarian-friendly companies, to support the Society's educational initiatives.[35]

In 2003, the Society launched a "Fishconception" campaign after a survey revealed that many restaurants, canteens, and hospitals mistakenly believed that vegetarians eat fish. The campaign aimed to correct this misconception and guide the catering industry on vegetarian standards.[36]

In 2017, the Vegetarian Society launched Veggie Lotto, the first vegetarian and vegan lottery in the UK. Tickets are priced at £1, with 50p allocated to the society. Funds raised support training for caterers, free courses for community groups and vulnerable individuals, and the promotion of vegetarian and vegan food.[37]

Historian Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska has noted that "against the background of growing concern about the environment, animal rights, and food safety the society has flourished in recent decades."[38]

In 2024, the Vegetarian Society announced a rebrand.[39] It has a new logo, rebranded magazine and website.[40] In the same year, the Society moved its head office to Ancoats, Manchester.[2]

Publications

[edit]

The Vegetarian Society first published The Vegetarian Messenger (1849–1860). It became The Dietetic Reformer and Vegetarian Messenger (1861–1897), The Vegetarian Messenger and Health Review (1898–1952), The Vegetarian (1953–1958) and The British Vegetarian (1959–1971).[41][42] In 1885, Beatrice Lindsay, a graduate from Girton College, Cambridge, became the first female editor of the Vegetarian Society's Dietetic Reformer and Vegetarian Messenger.[43] Early vegetarian writers for the Dietetic Reformer and Vegetarian Messenger in the 1870s and 1880s advocated biological evolution and reshaped it into a teleological progress.[44]

The Pod, formerly The Vegetarian, is the membership magazine of the Vegetarian Society and continues to be produced three times a year.[45]

Presidents

[edit]| 1847–1859 | James Simpson[46] |

| 1859–1870 | William Harvey[46] |

| 1870–1873 | James Haughton[46] |

| 1873–1884 | Francis William Newman[46] |

| 1884–1910 | John E. B. Mayor[47] |

| 1911–1914 | William E. A. Axon[48] |

| 1914–1933 | Ernest Bell[49] |

| 1937–1942 | Peter Freeman[50] |

| 1938–1959 | W. A. Sibly[51] |

| 1960–1987 | Gordon Latto[52] |

| 1987–1989 | Isobel Wilson[53] |

| 1996–1999 | Kathy Silk[54][55] |

| 1999–2005 | Maxwell G. Lee[54][56][57] |

Patrons

[edit]The Vegetarian Society has had several notable patrons. Rose Elliot, who became a patron in 2002, is an author of over fifty vegetarian cookbooks and received an MBE in 1999. Actor Jerome Flynn became a patron after adopting a vegetarian lifestyle at 18. Musician Paul McCartney and his late wife Linda became patrons in 1995. Fashion designer Stella McCartney and photographer Mary McCartney joined their parents as patrons. Television presenter Wendy Turner-Webster, a vegan, became a patron in 2004, promoting an animal-free diet.[58]

See also

[edit]- European Vegetarian Union

- International Vegetarian Union

- Linda McCartney Foods

- List of animal rights groups

- List of vegetarian and vegan organizations

- North American Vegetarian Society

- Veganism

- Vegetarian Society (Singapore)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "The Vegetarian Society of the United Kingdom Limited Group Annual Report and Financial Statements Year ended 31 March 2023". Register of charities. Charity Commission for England and Wales. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ a b Whelan, Dan (2024). "Vegetarian Society picks permanent Manchester home". North West Place. Archived from the original on 16 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "THE VEGETARIAN SOCIETY OF THE UNITED KINGDOM LIMITED - Charity 259358". Register of charities. Charity Commission for England and Wales. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "Our trademarks". Vegetarian Society. 18 July 2024. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ Qureshi, Waqas (30 March 2017). "Vegetarian Society launches vegan trademark for food packaging". Packaging News. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "Our trademarks". Vegetarian Society. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "McDonald's plant burger launch late to vegan party". 9 September 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "Home". National Vegetarian Week 2022. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ Twiggs, Hannah (28 April 2021). "Seven days' worth of meat-free dishes to get you through National Vegetarian Week". The Independent. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "The Vegetarian Society Cookery School". Independent Cookery Schools. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Davis, John. "The Origins of the 'Vegetarians'". International Vegetarian Union. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "The Vegetarian Movement in England 1847-1981". International Vegetarian Union. Autumn 1981. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Davis, John (2012). "A History of Veganism from 1806" (PDF). International Vegetarian Union. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Vegetarian Society - History". The Vegetarian Society. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Spencer, Colin. Vegetarianism: A History. Four Walls Eight Windows, 2000. pp. 238–246.

- ^ Holland, Evangeline (16 April 2008). "Vegetarianism". Edwardian Promenade. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ Newman, Francis William (1904), Lecture on Vegetarianism, F. Pitman, archived from the original on 14 April 2019, retrieved 18 May 2019

- ^ a b c d e f g h Spencer, Colin (1996). The Heretic's Feast: A History of Vegetarianism. UPNE. pp. 274–278. ISBN 978-0-87451-760-6.

- ^ a b c d e Gregory, James (29 June 2007). Of Victorians and Vegetarians: The Vegetarian Movement in Nineteenth-century Britain. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-85771-526-5.

- ^ Forward, Charles W. (1898). Fifty Years of Food Reform: A History of the Vegetarian Movement in England. London: The Ideal Publishing Union. p. 82

- ^ The National Union Catalog, Pre-1956 Imprints: A Cumulative Author List Representing Library of Congress Printed Cards and Titles Reported by Other American Libraries, Volume 631. Mansell. 1979. p. 507. ISBN 978-0720108637.

- ^ "History of Vegetarianism - Henry S. Salt (1851-1939)". International Vegetarian Union. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Puskar-Pasewicz, Margaret (16 September 2010). Cultural Encyclopedia of Vegetarianism. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 259–260. ISBN 978-0-313-37557-6.

- ^ a b c Yeh, Hsin-Yi (April 2013). "Boundaries, Entities, and Modern Vegetarianism: Examining the Emergence of the First Vegetarian Organization". Qualitative Inquiry. 19 (4): 298–309. doi:10.1177/1077800412471516. ISSN 1077-8004. S2CID 155099695.

- ^ Thomas, Keith (1984) Man and the Natural World. Changing Attitudes in England 1500–1800, p. 297.

- ^ In charts: Vegetarianism in India has more to do with caste hierarchy than love for animals Archived 1 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Scroll.in, 6 April 2017.

- ^ "London Vegetarian Association 1888-1969". International Vegetarian Union. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "International Vegetarian Congress 1907". International Vegetarian Union. 2024. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The Vegetarian Society UK - 21st Century Vegetarian - Society History". Vegetarian Society. 25 September 2006. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Courtney, Tina (April 1992). "Veggies at war". The Vegetarian. Vegetarian Society. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ a b McIlwain, Richard. "History". Vegetarian Society. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Vegetarian Society of the UK Seedling Symbol" (PDF). The Vegetarian Resource Group Vegetarian Journal (3). 2006.

- ^ "Devour the Earth". World Preservation Foundation. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013.

- ^ Calvert, Samantha Jane (July 2007). "A Taste of Eden: Modern Christianity and Vegetarianism". The Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 58 (3): 461–481. doi:10.1017/S0022046906008906. ISSN 0022-0469.

- ^ "History of the Vegetarian Awards". The Vegetarian Society. 8 December 2004. Archived from the original on 8 December 2004. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Leighton, Tommy (7 August 2003). "Vegetarians launch broadside at fish". Fruitnet. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Millis, Diane (4 May 2017). "UK gets its first Veggie lotto". NP NEWS. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina. (2010). Managing the Body: Beauty, Health, and Fitness in Britain 1880-1939. Oxford University Press. p. 337. ISBN 978-0199280520

- ^ Preston, Rob (2024). "Vegetarian Society announces £50,000 rebrand". Civil Society. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024.

- ^ Harle, Emily (2024). "175-year-old charity rebrands". Third Sector. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024.

- ^ Newton, David E. (2019). Vegetarianism and Veganism: A Reference Handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-4408-6763-7

- ^ "The Vegetarian Movement in England, 1847-1981" Archived 6 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine. International Vegetarian Union.

- ^ Young, L. (2021). The Vegetarian Messenger Archived 15 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Victorian Women's Writing. Palgrave. pp. 1-9. ISBN 978-3-030-02721-6

- ^ Kim, Haejoo (2021). "Vegetarian Evolution in Nineteenth-Century Britain". Journal of Victorian Culture. 26 (4): 519–533. doi:10.1093/jvcult/vcab040.

- ^ "Become a member". Vegetarian Society. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d Gregory, James Richard Thomas Elliott (2002). "Biographical Index of British Vegetarians and Food reformers of the Victorian Era". The Vegetarian Movement in Britain c.1840–1901: A Study of Its Development, Personnel and Wider Connections (PDF). Vol. 2. University of Southampton. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Venn, John; Venn, John Archibald (15 September 2011). "Mayor, John Eyton Bickersteth". Alumni Cantabrigienses: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, from the Earliest Times to 1900. Cambridge University Press. p. 379. ISBN 978-1-108-03614-6.

- ^ Calvert, Samantha Jane (2012). Eden's Diet: Christianity and Vegetarianism 1809–2009 (PDF). University of Birmingham.

- ^ Venn, John Archibald. (2011). Alumni Cantabrigienses: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, from the Earliest Times to 1900. Cambridge University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-1108036115

- ^ Wilson, David A. H. (2015). The Welfare of Performing Animals: A Historical Perspective. Springer. p. 99. ISBN 978-3-662-45833-4

- ^ A. & C. Black Ltd. (1964). Who Was Who, 1951-1960: A Companion to Who's Who, Containing the Biographies of Those Who Died During the Decade 1951-1960. London: Black. p. 998 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Leo, Sigrid De (1998). "Att-Gordon Latto has died at the age of 87". International Vegetarian Union. Archived from the original on 12 April 2024.

- ^ Lee, Maxwell G (October 1992). "Obituary: Isobel Wilson MBE". The Vegetarian. Archived from the original on 22 October 2010.

- ^ a b "History of The Vegetarian Society of the UK Ltd". International Vegetarian Union. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ "Kathy Silk". International Vegetarian Union. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ "Veggie Cool". Halifax Evening Courier. 2 July 1999. p. 12. (subscription required)

- ^ "Maxwell Lee". International Vegetarian Union. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ "Vegetarian Society Patrons". Vegetarian Society. 12 June 2010. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- James Gregory, Of Victorians and Vegetarians: The Vegetarian Movement in Nineteenth-Century Britain. London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2006. ISBN 978-1-84511-379-7