The Bulletin (Australian periodical)

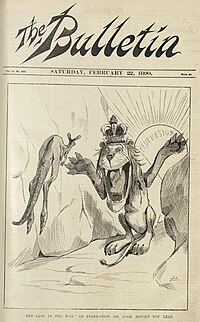

Front cover of the 22 February 1890 edition | |

| Editor-in-Chief | John Lehmann |

|---|---|

| Categories | News magazine |

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Founded | 1880 |

| Final issue | January 2008 |

| Company | Australian Consolidated Press |

| Country | Australia |

| Based in | Sydney, New South Wales |

| Language | English |

| ISSN | 1440-7485 |

The Bulletin was an Australian weekly magazine based in Sydney and first published in 1880. It featured politics, business, poetry, fiction and humour, alongside cartoons and other illustrations.

The Bulletin exerted significant influence on Australian culture and politics, emerging as "Australia's most popular magazine" by the late 1880s.[1] Jingoistic, xenophobic, anti-imperialist and republican, it promoted the idea of an Australian national identity distinct from its British colonial origins. Described as "the bushman's bible", The Bulletin helped cultivate a mythology surrounding the Australian bush, with bush poets such as Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson contributing many of their best known works to the publication. After federation in 1901, The Bulletin changed owners multiple times and gradually became more conservative in its views while remaining an "organ of Australianism". Although its popularity declined after World War I, it continued to serve as a vital outlet for new Australian literature.

It was revived as a modern news magazine in the 1960s, and after merging with the Australian edition of Newsweek in 1984[2] was retitled The Bulletin with Newsweek. Its final issue was published in January 2008, making The Bulletin Australia's longest running magazine.[3]

Early history

[edit]

The Bulletin was founded by J. F. Archibald and John Haynes in Sydney, New South Wales, with the first issue being published on 31 January 1880.[4] The original content of The Bulletin consisted of a mix of political comment, sensationalised news, and Australian literature.[5] For a short period in 1880, their first artist William Macleod was also a partner.[6][7]

The publication was folio size and initially consisted of eight pages, increasing to 12 pages in July 1880, and had reached 48 pages by 1899. The first issue sold for four pence, later reduced to three pence, and then, in 1883, was increased to six pence.[8] It is the namesake of the Sydney lane Bulletin Place, where the journal was published between 1880 and 1897, the year it moved to newer and larger offices in George Street.

During its first few decades, The Bulletin played a significant role in fostering nationalist sentiments in Australia. Its politics were also anti-imperialist, protectionist, insular, racist, republican, anti-clerical and masculinist—but not socialist. It mercilessly ridiculed colonial governors, capitalists, perceived snobs and social climbers, the clergy, wowsers (puritanical moralists), feminists and prohibitionists. It upheld trade unionism, Australian independence, advanced democracy and White Australia. It ran cartoons mocking the British, Chinese, Japanese, Indians, Jews, and Indigenous Australians.[9] The Bulletin decried the mistreatment of Indigenous people and regretted that, apart from the perpetrators of the Myall Creek massacre, offending colonists had escaped justice.[10] Even so, The Bulletin assumed that their "black brothers" would soon die out regardless, viewing them as an inferior race unfit "for the ordeal of civilisation", and any efforts to ameliorate their condition as futile.[11] In the early 20th century,[12] editor James Edmond changed The Bulletin's nationalist banner from "Australia for Australians" to "Australia for the White Man". An 1887 editorial laid out its reasons for choosing such banners:[13]

By the term Australian we mean not those who have been merely born in Australia. All white men who come to these shores—with a clean record—and who leave behind them the memory of the class distinctions and the religious differences of the old world ... all men who leave the tyrant-ridden lands of Europe for freedom of speech and right of personal liberty are Australians before they set foot on the ship which brings them hither. Those who ... leave their fatherland because they cannot swallow the worm-eaten lie of the divine right of kings to murder peasants, are Australian by instinct—Australian and Republican are synonymous.

The "Bulletin School"

[edit]

Temper, democratic; bias, offensively Australian.

— Joseph Furphy's description of his 1897 novel Such is Life, from his self-introduction to J. F. Archibald and later adapted as a slogan of the Bulletin School.[14]

From its outset, The Bulletin aimed to serve as a platform for young and aspiring Australian writers to showcase their works to large audiences. In 1886, it opened to submissions from all readers, calling for "original political, social or humorous matter, unpublished anecdotes and paragraphs, poems and short stories". Archibald encouraged contributors to "Make it short! Make it snappy, make it crisp, boil it down to a paragraph!" This resulted in what became known as "Bulletinese", described by P. R. Stephensen as "a clipped kind of slangy jargon [that] laid on local colour, not with a brush, but with a trowel."[15] The Bulletin subsequently became the focal point of an emerging literary nationalism known as the "Bulletin School", characterised by colloquial Australian language, energetic verse, dry humour and hard-edged realism. Popular with people who lived in the Australian bush, The Bulletin frequently reflected the life of the bush back to them, and by 1888, it was widely referred to as "the bushman's bible".[16] "The Bulletin brought the world to the bush, and made the bush part of the world", wrote Ann Curthoys and Julianne Schultz.[17] It was unique for publishing the contributions of ordinary bush people side by side with those from professional writers, and among folklorists and linguists, it is said to be without comparison as a source of Australianisms and bush lore.[18]

Critics of the Bulletin School found much of its output to be amoral, pessimistic and parochial. Vincent Buckley alleged that it was "a debilitating force in Australian culture" that "saw men as no different from, and with no more soul than, the gibber-plains, mulga, soil erosion, crows, dead sheep and withered outback mountains which regularly appeared in their poems."[19] The journal Australian Woman's Sphere, published by suffragist Vida Goldstein, wrote that there were two types of Bulletin School verse: "one a clothes-horse on which to hang bush terms, and the other an echo from the grave, with blighted love and regret in it". While commending the Bulletin School for being "racy of the soil" and displaying "unconventional local genius", Arthur Patchett Martin considered the defects of their verse to be "an absence of lucidity and an excess of expletives". English poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson read some Bulletin School poetry but declined to finish it, saying, "Unlike John the Baptist, I cannot live on locusts and wild honey."[20]

A number of leading members of the Bulletin School, often called bush poets, have become giants of Australian literature. Notable writers associated with The Bulletin during this period include:

- Francis Adams

- Julian Ashton

- William Astley

- Barbara Baynton

- George Lewis Becke

- Randolph Bedford

- Barcroft Boake

- E. J. Brady

- Christopher Brennan

- Victor Daley

- Frank Dalby Davison

- C. J. Dennis

- Albert Dorrington

- Edward Dyson

- John Farrell

- Ernest Favenc

- Joseph Furphy

- Mary Gilmore

- C. A. Jeffries ("Jeff")

- Henry Lawson

- Pattie Lewis ("Mab")

- Louise Mack

- Dorothy Mackellar

- Harry Morant ("The Breaker")

- John Shaw Neilson

- Will H. Ogilvie

- Nettie Palmer

- Vance Palmer

- Andrew Barton Paterson ("Banjo")

- Katherine Susannah Prichard

- Roderic Quinn

- Steele Rudd

- Alfred Stephens

- Douglas Stewart

- Ethel Turner

- Alexina Maude Wildman[21]

- David McKee Wright

Although cartooning featured in earlier Australian newspapers and journals, The Bulletin was the first to place heavy emphasis on it, and in the estimation of Bernard Smith, helped make Australia "one of the most important centres of black-and-white art in the world".[22] Many artists contributed illustrations to The Bulletin, including:

- Jimmy Bancks

- Les Dixon

- Ambrose Dyson

- Will Dyson

- Albert Henry Fullwood

- Alexander George Gurney

- Hal Gye

- Livingston Hopkins[23]

- George Washington Lambert

- Percy Leason

- Lionel Lindsay

- Norman Lindsay

- Ruby Lindsay

- David Low

- Jack Lusby

- William Macleod

- Frank P. Mahony

- Phil May

- Benjamin Minns

- Larry Pickering

- Norm Rice

- David Henry Souter

- Alfred Vincent

- Unk White

Cultural impact

[edit]

According to The Times of London, "It was The Bulletin that educated Australia up to Federation".[25] In South Africa, Cecil Rhodes regarded The Bulletin with "holy horror" and as a threat to his imperialist ambitions.[26] In a piece on Rhodes, W. T. Stead wrote that "The Bulletin he thus honoured by his dread is indeed one of the most notable journals of the world": "It is brilliant, lawless, audacious, scoffing, cynical, fearless, insolent, cocksure".[27] English author D. H. Lawrence felt that The Bulletin was "the only periodical in the world that really amused him", and often referred to it for inspiration when writing his 1923 novel Kangaroo.[28] Like Lawrence, the novel's English narrator considers it "the momentaneous life of the continent", and appreciates its straightforwardness and the "kick" in its writing: "It beat no solemn drums. It had no deadly earnestness. It was just stoical and spitefully humorous."[29] In The Australian Language (1946), Sidney Baker wrote: "Perhaps never again will so much of the true nature of a country be caught up in the pages of a single journal".

Bulletin School writers Henry Lawson, Mary Gilmore, and Banjo Paterson are among the four historical figures who have been commemorated on the Australian ten-dollar note.

A Woman's Letter

[edit]The Bulletin was seen to be lacking a "gossip column" such as that conducted by "Mrs Gullett" in The Daily Telegraph.[30] W. H. Traill, part-owner of the Bulletin, was aware of the literary talents of his sister-in-law Pattie Lewis, who had been, as "Mab", writing children's stories for the Sydney Mail. He offered the 17-year-old a column to be called A Woman's Letter, which involved reporting on the comings and goings of notable Sydney socialites. In time the column became quite popular, and reportedly the first item looked for in the magazine by both men and women. When Lewis married, it was she who recommended her successor, Ina Wildman, the audacious "Sappho Smith". Seven women wrote the "Woman's Letter" for The Bulletin:[31]

- 1881–1888 Pattie Lewis (died 1955) as "Mab"; married James Fotheringhame in 1886

- 1888–1896: Ina Wildman (died 1896) as "Sappho Smith"

- 1896–1898: Florence Blair (died 1937), daughter of David Blair, she married Archibald Boteler Baverstock in 1898.

- 1898–1901: Louise Mack (1870–1935) married John Percy Creed in 1896[32] and Allen I. Leyland in 1927.[33]

- 1901–1911: Agnes Conor O'Brien (died 1934) as "Akenehi" or "Lynette". She married artist and newspaperman William Macleod[34] in 1911

- 1911–1919: Margaret Cox-Taylor (died July 1939) as "Vandorian"

- 1919–1934: Nora Kelly as "Nora McAuliffe"

Later era

[edit]

The Bulletin continued to support the creation of a distinctive Australian literature into the 20th century, most notably under the editorship of Samuel Prior (1915–1933), who created the first novel competition.[5]

The literary character of The Bulletin continued until 1961, when it was bought by Australian Consolidated Press (ACP), merged with the Observer (another ACP publication), and shifted to a news magazine format.[5] Donald Horne was appointed as chief editor and quickly removed "Australia for the White Man" from the banner. The magazine was costing ACP more than it made, but they accepted that price "for the prestige of publishing Australia's oldest magazine".[9] Kerry Packer, in particular, had a personal liking for the magazine and was determined to keep it alive.[35]

In 1974, as a result of its publication of a leaked Australian Security Intelligence Organisation paper discussing Deputy Prime Minister Jim Cairns, the Whitlam government called the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security.[36]

In the 1980s and 1990s, The Bulletin's "ageing subscribers were not being replaced and its newsstand visibility had dwindled".[35] Trevor Kennedy convinced publisher Richard Walsh to return to the magazine. Walsh promoted Lyndall Crisp to be its first female editor, but James Packer then advocated that former 60 Minutes executive producer Gerald Stone be made editor-in-chief. Later, in December 2002, Kerry Packer anointed Garry Linnell as editor-in-chief. The magazine by this stage was dropping in circulation and running at a loss. On one occasion, Kerry Packer called Linnell to his office, and, when Linnell asked what Packer wanted for The Bulletin, Packer said: "Son, just make 'em talk about it."[37] When former Prime Minister Paul Keating sent Linnell a letter criticising the magazine and calling it "rivettingly mediocre", Linnell published the letter in the magazine, promoted that "Paul Keating Writes for Us", and awarded Keating with "Letter of the Week", with the prize for that being a year's subscription to the magazine.[38] In 2005, Linnell offered a $1.25-million reward to anyone who found an extinct Tasmanian tiger.[35]

Kerry Packer died in 2005, and in 2007 James Packer sold controlling interest in the Packer media assets (PBL Media) to the private equity firm CVC Asia Pacific.[35] On 24 January 2008, ACP Magazines announced that it was shutting The Bulletin. Circulation had declined from its 1990s' levels of over 100,000 down to 57,000,[9] which has been attributed in part to readers preferring the internet as their source for news and current affairs.[39]

Editors

[edit]

The Bulletin had many editors over its time in print, and these are listed below:

- J. F. Archibald

- John Haynes

- William Henry Traill[40]

- James Edmond

- Samuel Prior[41]

- John E. Webb[42]

- David Adams

- Donald Horne

- Peter Hastings[43]

- Peter Coleman

- Trevor Kennedy

- James Hall[44]

- Lyndall Crisp[45]

- Gerald Stone

- Max Walsh

- David Dale

- Paul Bailey[46]

- Garry Linnell[47]

- Kathy Bail[48]

- John Lehmann[49]

Columnists and bloggers

[edit]Regular columnists and bloggers on the magazine's website included:

- Patrick Cook

- Paul Daley[50]

- Julie-Anne Davies[51]

- Roy Eccleston[52]

- Ellen Fanning

- Katherine Fleming[53]

- Chris Hammer[54]

- Laurie Oakes

- Leo Schofield

- Adam Shand

- Terrey Shaw[55]

- Rebecca Urban[56]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Reinecke, Carl (2021). Books that Made Us. ABC Books, ISBN 9781460713501.

- ^ "The Online Books Page". Online Books. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ Jesse Hogan (24 January 2008). "The Bulletin shuts down". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ Bridget Griffen-Foley (2004). "From Tit-Bits to Big Brother: a century of audience participation in the media" (PDF). Media, Culture & Society. 26 (4). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "The Bulletin". AustLit.

- ^ "Mr. William MACLEOD". The Herald. No. 16, 255. Victoria, Australia. 24 June 1929. p. 4. Retrieved 24 February 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Death of Mr. William MACLEOD". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 28, 540. New South Wales, Australia. 25 June 1929. p. 12. Retrieved 24 February 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Stuart, Lurline (1979) Nineteenth century Australian periodicals: an annotated bibliography, Sydney, Hale & Iremonger, p.52. ISBN 0908094531

- ^ a b c Thompson, Stephen (January 2013). "1910 The Bulletin Magazine". Migration Heritage Centre NSW. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ The Bulletin (15 April 1882), "The Newsletter", p. 10

- ^ The Bulletin (9 June 1883), "Our Black Brothers", p. 6

- ^ William H. Wilde; Joy Hooton; Barry Andrews. The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature (2nd ed.). OUP. p. 130. ISBN 019553381X.

- ^ The Bulletin, 2 July 1887

- ^ Z. Angl. Am (1954), p. 429

- ^ Stephensen, P. R. (1936). The Foundations of Culture in Australia.

- ^ Biressi, Anita (2008). The Tabloid Culture Reader. McGraw-Hill Education, ISBN 9780335219315. p. 306

- ^ Curthoys, Ann; Schultz, Julianne (1999). Journalism: Print, Politics and Popular Culture. University of Queensland Press, ISBN 9780702231377. p. 90

- ^ Baker, Sidney (1976). The Australian Language. Sun Books. pp. 410–411

- ^ The Bulletin (9 September 1961), "Poetry in Corners". p. 5.

- ^ Patchett Martin, Arthur (1898). The Beginnings of an Australian Literature. H. Sotheran, pp. 43–46

- ^ Jill, Roe (1990). "Wildman, Alexina Maude (Ina) (1867–1896)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 12. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Smith, Bernard (1945). Place, taste and tradition: a study of Australian art since 1788. Ure Smith.

- ^ "Livingston Hopkins". Lambiek. 29 November 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ Galbally, Ann (30 December 2004). Charles Conder: The Last Bohemian. Melbourne University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-522-85084-0.

- ^ The Times, 31 August 1903, quoted in, Murray-Smith, Stephen (1987), The dictionary of Australian quotations, Melbourne, Heinemann, p.267. ISBN 0855610697

- ^ Hebdon, Geoffrey (2022). Zero Hour: A Countdown to the Collapse of South Africa's Apartheid System. Interactive Publications Pty, Limited, ISBN 9781922830043. p. 218

- ^ Stead, William Thomas (1905). The Review of Reviews, p. 471

- ^ Game, David (2016). D.H. Lawrence's Australia: Anxiety at the Edge of Empire. Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9781317155058, p. 177

- ^ Lawrence, D. H. (1923). "Chapter 14. Bits.". Kangaroo. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Half a Century of Journalism". The Telegraph (Brisbane). No. 18, 293. Queensland, Australia. 24 July 1931. p. 6. Retrieved 12 October 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "If Gossip We Must". The World's News. No. 1571. New South Wales, Australia. 20 January 1932. p. 15. Retrieved 16 February 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Woman's Column". Freeman's Journal. Vol. XLVII, no. 2706. New South Wales, Australia. 18 January 1896. p. 10. Retrieved 16 February 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Table Talk of the Week". Table Talk. No. 3101. Victoria, Australia. 13 October 1927. p. 4. Retrieved 16 February 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Obituary". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 30, 023. New South Wales, Australia. 26 March 1934. p. 16. Retrieved 16 February 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c d Haigh, Gideon (1 March 2008). "Packed It In: The Demise of The Bulletin". The Monthly.

- ^ Coventry, CJ. Origins of the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security (2018: MA thesis submitted at UNSW).

- ^ Knott, Matthew (3 July 2013). "The man to save Fairfax? The unstoppable rise of Garry Linnell". Crikey. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Lyons, John (25 January 2008). "Foreign buyers silence The Bulletin". News. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Steffen, Miriam (24 January 2008). "End of an era as The Bulletin closes". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- ^ B. G. Andrews, "Traill, William Henry (1843–1902)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1976, Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Peter Kirkpatrick, "Prior, Samuel Henry (1869–1933)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1988, Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "John E. Webb". AustLit.

- ^ Gavin Souter, "Hastings, Peter Dunstan (1920–1990)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 2007, Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "James Hall". AustLit.

- ^ "Crisp, Lyndall", Trove, 2009, retrieved 21 April 2015

- ^ "Paul Bailey". AustLit.

- ^ "Garry Linnell". AustLit.

- ^ "Kathy Bail". AustLit.

- ^ "John Lehmann". AustLit.

- ^ "Paul Daley". Austlit. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ ""The Bulletin prominent in Walkley Awards"". itechne. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ ""Our journalists"". The Advertiser. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ ""The West Australian – Katherine Fleming"". The West Australian. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ "Chris Hammer". Austlit. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ ""Chess by Terrey Shaw"". The Bulletin, 21 August 1984, p139. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ ""Rebecca Urban"". BuzzSumo. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Bennett, Bruce; Strauss, Jennifer, eds. (1998). The Oxford Literary History of Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-553737-6.

- Clay Djubal (2017). ""Looking in All the Wrong Places;" Or, Harlequin False Testimony and the Bulletin Magazine's Mythical Construction of National Identity, Theatrical Enterprise and the Social World of Little Australia, circa 1880-1920"". Mixed Bag: Early Australian Variety Theatre and Popular Culture Monograph Series. 3 (21 Sept. 2017). Have Gravity Will Threaten. ISSN 1839-5511.

- Dutton, Geoffrey (1964). The Literature of Australia. Melbourne: Penguin.

- Vance Palmer (1980). The Legend of the Nineties. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-83690-5.

- Patricia Rolfe (1979). The Journalistic Javelin: An Illustrated History of the Bulletin. Sydney: Wildcat Press. ISBN 978-0-908463-02-2.

- William Wilde; et al. (1985). The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554233-9.

External links

[edit]- Garry Wotherspoon (2010). "The Bulletin". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 2 October 2015. [CC-By-SA]

- The Bulletin at AustLit

- 1880 establishments in Australia

- 2008 disestablishments in Australia

- ACP magazine titles

- Antisemitism in Australia

- Defunct political magazines published in Australia

- Magazines disestablished in 2008

- Magazines established in 1880

- Magazines published in Sydney

- News magazines published in Australia

- Weekly magazines published in Australia