The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008

Hardcover edition | |

| Author | Paul Krugman |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Gray318 |

| Language | English |

| Subjects | 2008 financial crisis Economic history of the United States Economics Finance |

| Genre | Non-fiction Social sciences |

| Publisher | W. W. Norton & Company |

Publication date | December 2008 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print, e-book |

| Pages | 214 pp. |

| ISBN | 978-0393337808 |

The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008 is a non-fiction book by American economist and Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman, written in response to growing socio-political discourse on the return of economic conditions similar to The Great Depression.[1] The book was first published in 1999 and later updated in 2008 following his Nobel Prize of Economics.[2] The Return of Depression Economics uses Keynesian analysis of past economics crisis, drawing parallels between the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Depression. Krugman challenges orthodox economic notions of restricted government spending, deregulation of markets and the efficient market hypothesis. Krugman offers policy recommendations for the prevention of future financial crises and suggests that policymakers "relearn the lessons our grandfathers were taught by the Great Depression" and prop up spending and enable broader access to credit.[1][3][4]

The first edition included an economic analysis of the Asian Financial Crisis and the Latin American debt crisis.[3] The central concept of the book, as noted in the book's title, was a direct rejection of the public consensus that "the central problem of depression prevention has been solved", as stated by Robert Lucas in his presidential address to the American Economic Association.[1][5]

Following the shock of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) from 2007-2009, Krugman published an updated version of his book including an analysis of the recent GFC in his second edition The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. In response to the GFC, Krugman expressed his dissatisfaction with modern macroeconomic policy in the New York Times article How Did Economists Get It So Wrong?, highlighting what he considered the failure of neoclassical economics (i.e., Robert Lucas and Eugene Fama's efficient market hypothesis).[1][6] A similar sentiment is echoed in Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008.

Background

[edit]Editions

[edit]While The Return of Depression Economics explores depression economics through the lenses of the 1997 Asian financial crisis and Japan's Lost Decade, the 2008 update includes the liquidity crisis created in 2008 by misguided austerity measures.[7][2] In the book, Krugman examines the history of market crashes, such as the Panic of 1907 and the mid-1990s Tequila Crash and demonstrates how banking systems expose themselves to too much risk, leading to the loss of confidence and, ultimately, panic and capital flight.[8]

Paul Krugman

[edit]

Paul Krugman obtained his B.A. from Yale in 1974 and a PhD in economics from MIT in 1977. He has been a professor of economics at Yale, Stanford, and MIT. He is also an emeritus professor at Princeton. In 1982-1983 Krugman worked at The White House at the Council of Economic Advisers during Ronald Reagan's presidency. Following his revolutionary work in international trade and finance on New Trade Theory and New Economic Geography, Krugman received John Bates Clark Medal in 1991 and later the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2008.[9]

Outside of academia, Krugman has written on numerous macroeconomic issues relating to trade, healthcare, social policy and politics articles for the broader public in Foreign Affairs, Harvard Business Review, Scientific American . He regularly writes in his The New York Times column, writes in a blog named for his 2007 book The Conscience of a Liberal, and has published numerous books and textbooks.[9]

Key Theoretical Ideas

[edit]Keynesian economics

[edit]

Krugman's book The Return of Depression Economics challenges the perceived 1990's prosperity and misconception that economic depressions would not occur.[4] Krugman points to the need for Keynesian style of economics in response to economic depressions, rejecting neoclassical and orthodox economic rules, in favour of fiscal expenditure and increased money circulation. Krugman's solution is the Keynesian compact fiscal expenditure and expansion of money circulation.[10][5][2] Through the lens of Keynes's General Theory, Krugman analyses the economic crisis of Asia and Latin America, incorporating the usual Keynesian elements: a liquidity trap, rejection of orthodox economics, chronically volatile financial markets and mistreatment of aggregate demand/supply.[3]

Rejection of the efficient-market hypothesis

[edit]Krugman argues that economic analysis of recent financial crises provides evidence that markets consistently behave irrationally, directly contradicting neoclassical ideas of an efficient free market system.[3][6][1] Consequently, ineffective free markets will lead to inadequate demand, requiring government intervention to stimulate aggregate demand via fiscal expenditure.[3] Krugman illustrates that the Asian and Latin American financial crisis was a consequence of insufficient demand.[3] He suggests it is the volatility associated with the financial markets that reduced the effectiveness of economic policy in the recent economic crisis. Krugman challenges the effectiveness of the price mechanism whereby prices signal the efficient allocation of resources. As such, he argues for the incorporation of behavioural economics in the pursuit of policy and regulation of markets, to counteract the consequences of irrational decision making.[1]

The liquidity trap

[edit]Krugman introduces the notion of a liquidity trap in his analysis of Japan in the 1990s, the Asian financial crisis, Latin American crisis and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.[11][12][13] Liquidity traps are essentially a lack of circulation or growth in the supply of money in the economy.[11] Krugman argues that liquidity traps are caused by aggregate demand failures and produce negative natural interest rates.[11] Krugman identifies how misguided austerity measures with low interest rates led to the liquidity trap in 2008,[13]while large foreign denominated debt held by the private sector in Asia and Latin America led to the economic contraction.[12] Similarly, Krugman attributes the deregulation of the financial markets in Japan for the liquidity crisis. Regardless of the cause, Krugman highlights that monetary policy in such circumstances is ineffective given the economy is already at the zero lower bound (very low interest rates).Therefore, Krugman argues that policy should target increasing the rate of consumption and inflationary expectations to increase long run money supply.[11]

Content

[edit]Style, genre and structure

[edit]The book is a non-fiction economics novel that presents a simple, jargon free economic analysis of numerous historical financial crises across the world. Krugman provides an accessible read to a broad range of audiences, including academics and non-academics, as he compares the economic settings, policies and features that contributed to a financial crisis.[2][5] Krugman writes in a narrative style, using metaphors and analogies to illustrate his economic interpretations instead of referring to mathematical models.[2]

The book contains ten chapters which are divided into two themes. Chapters 1-4 presents the history of financial crises while Chapters 5-10 comment on the evolution of the modern global financial system and its features.[5]

Chapters

[edit]Introduction

[edit]Krugman introduces a brief historical account of the economic crises he will later present and discusses how he aims to present his book.

Chapter 1 "The Central Problem has been solved"

[edit]Krugman establishes his thesis – depression economics has returned. A historical account of the rise of capitalism and fall of socialism is given, and the subsequent economic success is attributed to this. Krugman mentions the Federal Reserve policy, Robert Lucas and Eugene Fama as key proponents of these neoclassical economic ideas, but argues they contradict current economic conditions.[5][4]

Chapter 2 "Warning Ignored: Latin America's Crisis"

[edit]Krugman criticises the misguided policies during the Mexican Tequila crisis from the 1980s-1990s that lead to an economic contagion throughout Latin America. He suggests that the overvalued currency in the 1980s and insufficient devaluation in the 1990s lead to the economic disaster. A timeline and sequence of events of the 1995 Mexican tequila crisis and its spill over into Latin America and Argentina are presented. Economic reforms in Argentina and Mexico led to an overvalued currency, and efforts to hamper currency speculation with a devaluation was insufficient resulting in the economic crisis.[5][4]

Chapter 3 "Japan's trap"

[edit]Krugman uses the liquidity trap in 1990s Japan to signal the return of depression economics. Krugman suggests that despite Japan being the second largest economy at the time, and a creditor nation, financial liberalisation, and deregulation in the 1980s led to deflation and a recession. Krugman identifies the stagnant growth in money supply as the crux of Japan's liquidity trap. As a result, low interest rates rendered monetary policy ineffective in stimulating economic growth. Instead, Krugman recommends printing money to increase inflationary expectations and encourage more consumption.[5][4]

Chapter 4 Asia's Crash

[edit]This chapter outlines that sequence of events following the devaluation of the Thai Baht in 1997 which had a flow on effect on Malaysia's ringgit, Indonesia and even South Korea. Krugman highlights how the combination of poor investments, low interest rates and increasing deregulation, increased dependence on foreign currencies and lead to bank runs. Krugman explains how an influx of capital into emerging Asian markets was mostly directed to speculation instead of infrastructure development. Consequently, when the Thai government maintained a fixed exchange rate, the economy ran a deficit 8% of GDP with imports exceeding exports. Krugman draws parallels with the economic situation in Japan's 1980 bubble economy and the Mexican tequila crisis. He emphasises the self-validating panic within the Asian economies and advocates for swift government intervention.[5][4]

Chapter 5 Policy Perversity

[edit]Krugman criticises International Monetary Fund and US Treasury policy response to the Asian Financial Crisis which focused on managing speculation and restoring market confidence. This misguided policy, Krugman suggests, urges reduced fiscal expenditure, increased taxes, and interest rates. Krugman advocates for the time honoured "Keynesian compact", fiscal expenditure and expansion of money circulation.[5][4][2]

Chapter 6 Masters of the Universe

[edit]In response to the GFC, Krugman suggests complex financial innovations, derivatives, and short sales are to blame. He critiques the social structures and governing bodies in America for their flawed models of long-term capital management. He provides insights into the role of hedge funds in the Asian financial crisis and George Soros and the British Pound and Ruble. Krugman stressed the importance of government intervention in these scenarios for preventing full scale panic.[5][4]

Chapter 7 Greenspan's Bubbles

[edit]

Krugman attributes blame to Alan Greenspan for the Dot-com and housing bubbles in the early 2000s. He details the flourishing economic conditions in which Greenspan became the chairman of the Federal Reserve and his subsequent reluctance to raise interest rates. Krugman suggests that loose monetary policy led to irrational investor behaviour and the stock bubble burst. Greenspan then lowered the interest rate to 1% which eventually stimulated the economy but led to larger mortgages, increased prices, and the housing bubble. further increased prices and led to the housing bubble.[5][4]

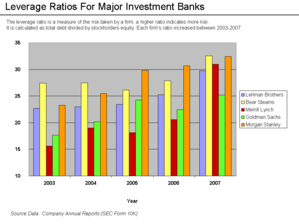

Chapter 8 "Banking in the Shadows"

[edit]Krugman suggests that the 1999 repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act led to the development of banking institutions that weren't regulated by the Federal Reserve. Krugman suggests that this shadow banking system was the root of the global financial crisis and current financial crisis and as such should be regulated.[5][4]

Chapter 9 "The Sum of all Fears"

[edit]Krugman highlights the importance of identifying bubbles and isolates similarities between the onset of the GFC, The Great Depression, Japan's lost decade and the Asian financial crisis. He thoroughly analyses the symptoms leading to the GFC including US liquidity, disruption of capital flows and a bursting real-estate bubble that deflated in 2005, but wasn't noticed until 2006.[5][4]

Chapter 10 "The return of depression economics"

[edit]Krugman strongly advocates for fiscal expenditure, a key Keynesian doctrine, to boost aggregate demand and economic output. According to Krugman, depression economics concerns identifying unemployed resources and putting them to good use as opposed to economic policy concerning consumer and investor confidence. He suggest that governments should run deficits to stimulate the economy.[5][4]

Critical reception

[edit]Policy recommendation

[edit]A common criticism of Krugman's policy recommendation is the non-specific regulatory reforms and stimulus packages recommended to solve the identified economic problems.[15][4] This ambiguity is seen in the recommendations to regulate anything that requires rescuing in a financial crisis.[4]

Krugman challenges the dominant neoclassical paradigm's ability to predict the business cycle, but Rankin acknowledges a more constructive critique is required.[1] Economists that endorse Krugman's policy recommendation acknowledge that little is mentioned about the adverse implications of his policy including increasing debt, risk of hyperinflation, speculative threat, and opportunists. Additionally, Krugman does not comment on the technical and financial limitations of policy implementation in a global financial market. Once an economy has recovered, Krugman advocates that preventative measures should be placed in the financial system, but implementing these reforms may be challenging when financial players are operating in their usual profit-maximising way.[2]

Krugman suggests stimulating demand via increasing consumption, investment, and government expenditure, but does not explain how to fund an increase in income. An increase in government income can be funded by debt or tax, and although neither will more effectively stimulate the economy according to the Ricardian equivalence theorem, will each have differing socio-political and economic implications which Krugman does not explore. Future consumer confidence may be negatively impacted when they see increased expenditure and cannot foresee an indefinite increase in income.[6] Therefore, Cochrane says that the economic stimulus provided by fiscal expenditure may be short-term considering future consumer confidence may be damped. Cochrane and Rankin have critiqued that market failures should not be fixed by typical Keynesian fiscal expenditure and exploitation of fiscal multipliers, instead suggesting monetary expansion and money printing.[6][1]

Krugman's recommendations can be categorised into 4 main remedies:

1. Unfreeze capital markets

2. Fiscal spending on infrastructure development and directly financing non-financial sector

3. Global rescue orientated to developing countries

4. Regulation of financial markets to prevent future crisis[15]

Free market perspectives

[edit]

Krugman mirrors Keynes's sentiment, "Keynes considered it a very bad idea to let such markets… dictate important business decisions" highlighting the excessive volatility of markets as symbolic of market inefficiency and the need for government regulation.[6] In Krugman's words, "financial economists believe we should put capital development of the nation in the hands of what Keynes had called a 'casino'".[6] However, there may be insufficient evidence for Krugman to overturn the efficient market hypothesis and Krugman's insights do not differ much from typical Keynesian ideas where the irrational financial sector is to blame.[1]

An alternative to Krugman's irrational free market hypothesis, is that governments may similarly be just as irrational, and influenced by political objectives. Cochrane cites the Bernie Madoff Ponzi scheme as evidence for the government's failure to regulate. Irrational decision making and human behaviour is not limited to the consumer, but prevalent throughout government and financial institutions as well. An argument opposing government manipulation of markets is when the free market causes less harm than the government.[6]

Cochrane points out that "stable price growth would be a violation of efficiency as it implies easy profits".[6] That is, efficiency does not necessarily reflect stability and volatility is a natural feature of the economic mechanism. Concurring with Cochrane, Ritenour criticises Krugman's belief in the inherent instability of the free market and assumption that prices are relatively inelastic in response to surpluses in demand or supply. Krugman assumes inflation is a normal part of the free market and therefore in his book does not explain the causes of monetary inflation in Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, or Thailand.[3] Allocation of resources is most efficient with government intervention according to Krugman, but Ritenour suggests that free markets give more choice and incentive to save and spend wisely in the area of most public demand.[3]

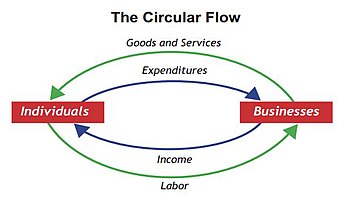

Economic model and analysis

[edit]The book presents a non-mathematical analysis of economics catered to a broad academic and non-academic audience, maintaining a precise historical and political account of economic crisis.[4] The historical analysis of the Great Depression and Mexican tequila crisis given are well detailed, but other cases are arguably less detailed.[2] Economists such as Cochrane, Ritenour and Keith Rankin, criticise the oversimplification of necessary mathematical models and suggest that without these, the arguments lack logic and consistency. Krugman's analysis may be described as "descriptive storytelling rather than rigorous analysis" and is only partly successful in presenting complex cases with generalised findings.[2] On the other hand, Rankin supports Krugman's endorsement of circular flow models and suggests they are necessary for current economic analysis.[1] Some economists claim that Krugman's casual treatment of concepts from both a qualitative and modelling perspective render it vulnerable to criticism from orthodox and neoclassical economist. Krugman does not differentiate between the types of actors, whether public or private, nor the different geographical scales in which they operate, and therefore offers little acknowledgement of the complex interdependent dynamics in a global financial environment.[2] These loose economic foundations produce policy recommendations that may lack scientific rigour according to some economist,[3][2] and while the important ideas are covered, no alternative analysis is provided.[1]

Ritenour claims that Krugman's economic analogies lack real world applicability and are flawed by the assumption of inelastic prices (no changes to prices are mentioned) and homogeneity of goods. This is evident in the baby-sitting analogy where a sudden increase in demand ensues, but the origin of this demand is not explained.[3] Similarly, Cochrane critiques Krugman for not having an "operational procedure for identifying bubbles" with no "long-term strategy". In the book's analysis of the Asian and Latin American financial crisis, other than explaining how the lack of confidence spiralled into a panic and free markets cannot self-regulate, Krugman does not explain the causes of the insufficient demand. Ritenour states that Krugman "overlooks the 'catalyst' of economic panic in the Latin and Asian crisis", the rapid increase in money supply and inflation.[3]

Krugman's recommendation to incorporate behavioural economics into new models is not novel.[6] Krugman argues that economists can make useful predictions incorporating behavioural finance and pursuing regulation that counteracts the adverse consequences of irrational financial decision making.[1] Beyond an explanatory model, Krugman's insights on the diversity of socio-economic and historical factors make it difficult to draw predictive models.[2] Krugman's praise for Robert Shiller, a behavioural financier who predicted the last economic downtown, should also be more critically evaluated.[6] Cochrane's criticism of Krugman's economic analysis can be summarised in his statement "The economist's job is not to "explain" market fluctuations after the fact or to give a pleasant story on the evening news about why markets went up or down".[6] In a similar line of thought, Rankin states that Krugman is "unable to extend his message beyond the combined insights of Keynes and findings of new behavioural economist".[1]

Inadequate supply not demand

[edit]

Krugman argues that volatile speculative behaviour causes oscillations in confidence and subsequently repeated crisis of insufficient demand, with his policy recommendations specifically targeting demand failures.[3] Krugman and Hick share overarching concerns that demand failures cause liquidity traps and pervading negative natural interest rates.[11] Krugman highlights the ineffectiveness of cutting interest rates when insufficient demand exists[11] and claims that monetary inflation is necessary to stimulate demand.[3]

However, Ritenour points out the age-old problem of finite resources and infinite demand. Krugman's management of demand and inflationary expectations via monetary and credit expansion by governments, may inefficiently allocate capital to the wrong resource. This is termed, malinvestment. Ritenour proposes that recessions are caused by malinvestments when monetary policy, credit expansion and lower interest rates incentivises firms to invest too much in the production for preferred goods and not enough for less preferred goods. This results in an oversupply of preferred goods and therefore inadequate demand for these goods. Ritenour states that it's an inappropriate allocation of resources that leads to a recession while Krugman argues that it is inadequate demand.[3]

Causes of the GFC

[edit]

Throughout the book Krugman implies that deregulation of financial markets led to bank runs and excessive risk taking at the height of the GFC. However, other economists including Cochrane suggest an overregulation of banks and accumulation of short-term debt (facilitated by deposit insurance and credit guarantees designed to prevent bank runs) incentivised excessive risk-taking. Cochrane recommends incentivising banks and financial institutions to prevent another sovereign debt crisis. According to Krugman's contemporaries, the Federal Reserve Board's attempts to control interest rates during the GFC may have contributed to the crisis, and have brought into question the ability of the Federal Reserve Board to maintain independence. Krugman does not appear to comment on this. Furthermore, other than "setting interest rates at zero and waiting for fiscal policy", Krugman does not comment on the other government mechanisms employed during the GFC.[6]

Political intention

[edit]Krugman's book is mostly a macroeconomic guidebook that advocates for regulatory reform of the financial system, including the reduction of interest rates and increasing budget deficits to counter recessions. That includes regulation of hedge funds and auction rate security systems.[2] Much of his book is also an endorsement of Keynesian economics and the Keynesian solution to economics crises: fiscal expenditure and expansion of money circulation. Given the broad reach of Krugman's book the academic merit of this book may be limited.[2]

Significance for geography and regional research

[edit]Indirectly, the book's identification of causes of economic crises has implications for a globalised commercial banking system and economic geography. However, the book provides very brief insight into new economic geography with minimal analysis of the crises through a regional and multi-levelled government lens. Although the geographical factors that accentuate an economic recession such as corporate behaviour and sociocultural features are not examined by Krugman, his book perhaps highlights the gap between 'real' economic geography and world events.[2]

Ongoing impact

[edit]In the post-pandemic world with decreased demand in most economies, Krugman's book may be more relevant today considering the increase in welfare economics favouring public health. Krugman's interventionist macroeconomic policies and focus on remedying demand failure seems valid for the COVID-19 recession. Given the current scenario, Krugman's comments on preventing a liquidity and solvency crisis would suggest similar policy recommendations to those mentioned in his book. Krugman's book can be considered thought-provoking due to its continued relevance, richness of ideas, broad analysis and interpretation of crises.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Rankin, Keith (2010). "Krugman on the Malaise of Modern Macro: Critique Without Alternative". Agenda: A Journal of Policy Analysis and Reform. 17 (1): 95–100. doi:10.22459/ag.17.01.2010.08. ISSN 1322-1833.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Klagge, Britta; Fromhold-Eisebith, Martina; Fuchs, Martina (2010-03-25). "The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008". Regional Studies. 44 (3): 383–385. Bibcode:2010RegSt..44..383K. doi:10.1080/00343401003707367. ISSN 0034-3404. S2CID 154414843.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ritenour, Shawn (2000-03-01). "Post-Modern Economics: The Return of Depression Economics. By Paul Krugman. New York: W.W. Norton and company, 1999". The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics. 3 (1): 79–83. doi:10.1007/s12113-000-1015-3. ISSN 1936-4806. S2CID 154080149.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ahmad, Nazneen; Mazumder, M Imtiaz (2012-09-01). "The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008, by Paul Krugman". Eastern Economic Journal. 38 (4): 552–554. doi:10.1057/eej.2010.36. ISSN 1939-4632. S2CID 153995038.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Mahmood, Mahmood (2010). "The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008". Applied Economics. 17 (4): 78–87. doi:10.1080/13504850701748909. ISSN 0858-9291. S2CID 154617186.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cochrane, John H. (2011). "HOW DID PAUL KRUGMAN GET IT SO WRONG?1: iea economic affairs". Economic Affairs. 31 (2): 36–40. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0270.2011.02077.x. S2CID 152347460.

- ^ Gaspar, José M. (2020-04-01). "Paul Krugman: contributions to Geography and Trade". Letters in Spatial and Resource Sciences. 13 (1): 99–115. doi:10.1007/s12076-020-00247-0. ISSN 1864-404X. S2CID 219041521.

- ^ Leith, William (December 26, 2008). "Still looking for a free lunch". The Guardian.

- ^ a b "Paul Krugman | Biography, Nobel Prize, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ Ritenour, Shawn (2000-03-01). "Post-Modern Economics: The Return of Depression Economics. By Paul Krugman. New York: W.W. Norton and company, 1999". The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics. 3 (1): 79–83. doi:10.1007/s12113-000-1015-3. ISSN 1936-4806. S2CID 154080149.

- ^ a b c d e f Boianovsky, Mauro (2004-12-01). "The IS-LM Model and the Liquidity Trap Concept: From Hicks to Krugman". History of Political Economy. 36 (Suppl_1): 92–126. doi:10.1215/00182702-36-suppl_1-92. ISSN 0018-2702. S2CID 11131014.

- ^ a b Eggertsson, Gauti B.; Krugman, Paul (2012-08-01). "Debt, Deleveraging, and the Liquidity Trap: A Fisher-Minsky-Koo Approach*". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 127 (3): 1469–1513. doi:10.1093/qje/qjs023. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ^ a b Gaspar, José M. (2020-04-01). "Paul Krugman: contributions to Geography and Trade". Letters in Spatial and Resource Sciences. 13 (1): 99–115. doi:10.1007/s12076-020-00247-0. ISSN 1864-404X. S2CID 219041521.

- ^ "EconStats : S&P Global 1200 daily Index and Correlations with SP500. | stock markets". www.econstats.com. Retrieved 2022-05-27.

- ^ a b c Wanniarachchige, M. K. (2022-03-22). "Book Review: COVID-19 Pandemic and the Return of Depression Economics: The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008, Paul Krugman (W.W. Norton & Company, 1st Edition (2009), Pages: 191)". Asian Journal of Management Studies. 2 (1): 130–134. doi:10.4038/ajms.v2i1.47. ISSN 2783-851X. S2CID 247645822.

External links

[edit]- The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008 at Krugmanonline.com