The Rescuers

| The Rescuers | |

|---|---|

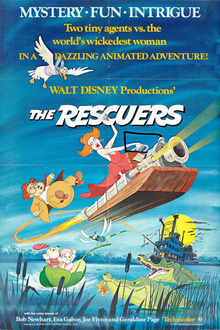

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Story by |

|

| Based on | The Rescuers Miss Bianca by Margery Sharp |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Artie Butler |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 77 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7.5 million |

| Box office | $169 million[1] |

The Rescuers is a 1977 American animated adventure comedy-drama film produced by Walt Disney Productions and released by Buena Vista Distribution. Bob Newhart and Eva Gabor respectively star as Bernard and Bianca, two mice who are members of the Rescue Aid Society, an international mouse organization dedicated to helping abduction victims around the world. Both must free 6 year old orphan Penny (voiced by Michelle Stacy) from two treasure hunters (played by Geraldine Page and Joe Flynn), who intend to use her to help them obtain a giant diamond. The film is based on a series of books by Margery Sharp, including The Rescuers (1959) and Miss Bianca (1962).

An early version of The Rescuers entered development in 1962, but was shelved due to Walt Disney's dislike of its political overtones. During the 1970s, the film was revived as a project intended for the younger animators, with the oversight of the senior staff. Four years were spent working on the film. The Rescuers was released on June 22, 1977, to positive critical reception and became a box office success, earning $48 million against a budget of $7.5 million during its initial theatrical run. It has since grossed a total of $169 million after two re-releases in 1983 and 1989. Due to the film's success, a sequel titled The Rescuers Down Under was released in 1990, which made this film the first Disney animated film to have a sequel.

Plot

In an abandoned riverboat in Devil's Bayou, Louisiana, a 6 year old orphan named Penny drops a message in a bottle, containing a plea for help, into the river. The Rescue Aid Society, an international mouse organization inside the United Nations, finds the bottle when it washes up in New York City. The Hungarian representative, Miss Bianca, volunteers to accept the case. She chooses Bernard, a stammering janitor, as her co-agent. The two visit Morningside Orphanage, where Penny lived, and meet an old cat named Rufus. He tells them about a woman named Madame Medusa who once tried to lure Penny into her car, prompting the mice to investigate her pawn shop for clues.

At the pawn shop, Bianca and Bernard discover that Medusa and her partner, Mr. Snoops, are searching for the world's largest diamond, the Devil's Eye. The mice learn that Medusa and Snoops are currently at the Devil's Bayou with Penny, whom they have kidnapped and placed under the guard of two trained crocodiles, Brutus and Nero. With the help of an albatross named Orville and a dragonfly named Evinrude, the mice follow Medusa to the bayou. There, they learn that Medusa plans to force Penny to enter a small blowhole that leads down into a blocked-off pirates' cave where the Devil's Eye is located.

Bernard and Bianca find Penny and devise a plan of escape. They send Evinrude to alert the local animals, who loathe Medusa, but Evinrude is delayed when he is forced to take shelter from a cloud of bats. The following morning, Medusa and Snoops send Penny down into the cave to find the gem. Unbeknownst to Medusa, Bianca and Bernard are hiding in Penny's dress pocket. The three soon find the Devil's Eye within a pirate skull. As Penny pries the mouth open with a sword, the mice push the gem through it, but soon the oceanic tide rises and floods the cave. The three barely manage to escape with the diamond.

Medusa betrays Snoops and hides the diamond in Penny's teddy bear, while holding Penny and Snoops at gunpoint. When she trips over a cable set as a trap by Bernard and Bianca, Medusa loses the bear and the diamond to Penny, who runs away with them. The local animals arrive at the riverboat and aid Bernard and Bianca in trapping Brutus and Nero, then set off Mr. Snoops's fireworks to create more chaos. Meanwhile, Penny and the mice commandeer Medusa's swamp-mobile, a makeshift airboat. Medusa unsuccessfully pursues them, using Brutus and Nero as water-skis. As the riverboat sinks from the fireworks' damage, Medusa crashes and is left clinging to the boat's smoke stacks. Mr. Snoops escapes on a raft and laughs at her, while the irritated Brutus and Nero turn on her and circle below.

Back in New York City, the Rescue Aid Society watch a news report of how Penny found the Devil's Eye, which has been given to the Smithsonian Institution while it is implied that Medusa and Mr. Snoops have been arrested. It also mentions she has been adopted. The meeting is interrupted when Evinrude arrives with a call for help, sending Bernard and Bianca on a new adventure.

Cast

- Bob Newhart as Bernard, Rescue Aid Society's timid janitor, who reluctantly tags along with Miss Bianca on her journey to the Devil's Bayou to rescue Penny. He is highly superstitious about the number 13 and dislikes flying (the latter being a personality trait of Newhart).

- Eva Gabor as Miss Bianca, the Hungarian representative of the Rescue Aid Society. She is sophisticated and adventurous, and fond of Bernard, choosing him as her co-agent as she sets out to rescue Penny. Her Hungarian nationality was derived from that of her voice actress.

- Geraldine Page as Madame Medusa, a greedy, redheaded, wicked pawn-shop owner. Upon discovering the Devil's Eye diamond hidden in a blowhole, she kidnaps the small orphan, Penny, to retrieve it for her, as Penny is the only one small enough to fit in it. She has two pet crocodiles, who turn on her after she is thwarted by Bernard, Bianca, and Penny.

- Joe Flynn as Mr. Snoops, Medusa's clumsy and incompetent business partner, who obeys his boss's orders to steal the Devil's Eye in exchange for half of it. Upon being betrayed by Medusa, however, he turns on her and flees by raft, laughing at her. This was Flynn's final role, with the film being released after his death in 1974.

- Jeanette Nolan as Ellie Mae and Pat Buttram as Luke, two muskrats who reside in a Southern-style home on a patch of land in Devil's Bayou. Luke drinks very strong, homemade liquor, which is used to help Bernard and Evinrude regain energy when they need it. Its most important usage is for fuel for powering Medusa's swamp-mobile in the film's climax.

- Jim Jordan as Orville (named after Orville Wright of the Wright brothers, the inventors of the airplane; most likely influenced from Bob Newhart's stand-up sketch "Merchandising the Wright Brothers"), an albatross who gives Bernard and Bianca a ride to Devil's Bayou. Jordan, 80 years old by the time the film was completed, had been lured out of retirement and had not performed since the death of his wife and comic partner Marian in 1961; it would serve as Jordan's last public performance.

- John McIntire as Rufus, an elderly cat who resides at Morningside Orphanage and comforts Penny when she is sad. Although his time onscreen is rather brief, he provides the film's most important theme, faith. He was designed by animator Ollie Johnston, who retired after the film following a 40-year career with Disney.

- Michelle Stacy as Penny, a lonely six-year-old orphan girl, residing at Morningside Orphanage in New York City. She is kidnapped by Medusa in an attempt to retrieve the world's largest diamond, the Devil's Eye.

- Bernard Fox as Mr. Chairman, the chairman to the Rescue Aid Society.

- Larry Clemmons as Gramps, a grumpy, yet kind old turtle who carries a brown cane.

- James MacDonald as Evinrude (named after a brand of outboard motors), a dragonfly who mans a leaf boat across Devil's Bayou, giving Bernard and Miss Bianca a ride across the swamp waters.

- George Lindsey as Deadeye, a fisher rabbit who is one of Luke and Ellie Mae's friends.

- Bill McMillian as TV Announcer

- Dub Taylor as Digger, a mole.

- John Fiedler as Deacon Owl

Production

In 1959, the book The Rescuers by Margery Sharp had been published to considerable success. In 1962, Sharp followed up with a sequel titled Miss Bianca. That same year, the books were optioned by Walt Disney, who began developing an animated film adaptation. In January 1963, story artist Otto Englander wrote a story treatment based on the first book, centering on a Norwegian poet unfairly imprisoned in a Siberia-like stronghold known as the Black Castle.[2] The story was revised with the location changed to Cuba, in which the mice would help the poet escape into the United States.[3] However, as the story became overtly involved in international intrigue, Disney shelved the project as he was unhappy with the political overtones.[4] In August 1968, Englander wrote another treatment featuring Bernard and Bianca rescuing Richard the Lionheart during the Middle Ages.[2]

A total of four years were spent working on The Rescuers, which was made on a budget of $7.5 million.[5] During the early 1970s, The Rescuers reentered development as a project for the young animators, led by Don Bluth, with the studio planning to alternate between full-scale "A pictures" and smaller, scaled-back "B pictures" with simpler animation. The animators had selected the most recent book, Miss Bianca in the Antarctic, to adapt from. The new story involved a King penguin deceiving a captured polar bear into performing in shows aboard a schooner, causing the unsatisfied bear to place a bottle that would reach the mice. Fred Lucky, a newly hired storyboard artist, was assigned to develop the story adaptation, alongside Ken Anderson.[6] This version of the story was dropped, to which Lucky explained the Arctic setting "was too stark a background for the animators."[7] Vance Gerry, also a storyboard artist, also explained director Wolfgang Reitherman "decided not to go with Fred Lucky's version. He said, "'It's too complicated. I want a simple story: A little girl gets kidnapped and the mice try to get her back, period.'"[8] According to Burny Mattinson, he stated: "Our problem was that the penguin wasn't formidable or evil enough for the audience to believe he would dominate the big bear. We struggled with that for a year or so. We changed the locale to somewhere in America and it was now a regular zoo and we tried to come up with something with the bear in the zoo and needing to be rescued but that didn't work either."[3]

In that version, the bear character was still retained, but was renamed Louie the Bear. Jazz singer Louis Prima was cast in the role and had recorded most of the dialogue and multiple songs that were composed by Floyd Huddleston.[9] The writers also expanded the role of his best friend, Gus the Lion.[10] Huddleston had stated, "It's about two animals. One is Louis Prima — he's the polar bear — and Redd Foxx is the lion ...Louis gets cornered into leaving and going to the South Pole where he can make himself a bigger star. But he gets homesick; he feels fooled. They send out little mice as 'rescuers'."[11] By November 1973, the role of Louie the Bear had been heavily scaled back and then eliminated.[10] In one version, the bear was meant to be Bernard and Bianca's connection to Penny. Gerry explained, "We developed the sequence where, while the two mice are searching for clues as to where Penny has been taken, they come across this bear who she had been friends with because the orphanage where Penny was living was near the zoo."[3] In the final film, the idea was reduced to a simple scene where Bernard enters a zoo and hears a lion's roar that scares him away.[8]

While promoting the release of Robin Hood (1973) in Europe, Reitherman stated: "I took Margery Sharp's books along and there was in there a mean woman in a crystal palace. When I got back I called some of the guys together and I said, 'We've got to get a villain in this thing.'"[2] The villainess and her motive to steal a diamond was adapted from the Diamond Duchess in Miss Bianca. The setting was then changed to the bayous found in the Southern United States.[7] By August 1973, the villainess was named the Grand Duchess with Phyllis Diller cast in the role.[10] A month later, Ken Anderson began depicting Cruella de Vil, the villainess from One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), as the main antagonist of the film.[10][13] Anderson had drawn several sketches of Cruella de Vil sporting alligator-leathered chic attire and sunglasses; one sketch depicted her wearing bell-bottom pants and platform shoes.[14] However, several staff members such as animator Ollie Johnston stated it felt wrong to attempt a sequel for the character.[15] Furthermore, Mattinson explained that Milt Kahl did not want to animate Cruella de Vil. "Milt, of course, was very strong against that, 'Oh, no no. We're gonna have a new character. I'm not gonna do Cruella'," Mattinson recalled, "Because he felt that Marc [Davis] had animated Cruella beautifully. He was not gonna go and take his character."[13]

The new villain was named Madame Medusa, and her appearance was based on Kahl's then-wife, Phyllis Bounds (who was the niece of Lillian Disney), whom he divorced in 1978.[16] This was Kahl's last film for the studio, and he wanted his final character to be his best. He was so insistent on perfecting Madame Medusa that he ended up doing almost all the animation for the character himself.[17] The kidnapped child Penny was inspired by Patience, the orphan in the novel. The alligator characters Brutus and Nero was based on the two bloodhounds, Tyrant and Torment, in the novels. For the henchman, the filmmakers adapted the character, Mandrake, into Mr. Snoops. His appearance was caricatured from John Culhane, a journalist, who had been interviewing animators at the Disney studios.[15][18] Culhane claimed he was practically tricked into posing for various reactions, and his movements were imitated on Mr. Snoops's model sheet. However, he stated, "Becoming a Disney character was beyond my wildest dreams of glory."[19]

The writers had considered depicting Bernard and Bianca as married professional detectives, but decided that depicting them as novices in a new relationship was more compelling and romantic.[7][20] For the supporting characters, a pint-sized swamp mobile for the mice—a leaf powered by a dragonfly—was created. As they developed the comedic potential of displaying his exhaustion through buzzing, the dragonfly grew from an incidental into a major character.[21] Veteran sound effects artist and voice actor Jimmy MacDonald came out of retirement to provide the effects.[22] Additionally, the local swamp creatures were originally written as a dedicated home guard that drilled and marched incessantly. However, the writers rewrote them into a volunteer group of helpful little bayou creatures. Their leader, a singing bullfrog, voiced by Phil Harris, was cut from the film,[23] as were lines characterizing muskrat Ellie Mae as their outspoken boss.[24] For Bernard and Bianca's transportation, a pigeon was proposed (specifically one that would be catapulted, repurposing an unused gag from Robin Hood),[25] until Johnston remembered a True-Life Adventures film featuring albatrosses and their clumsy take-offs and landings, leading him suggest that ungainly bird instead.[26] A scene of the mice preparing for their adventure, with Bianca choosing outfits and Bernard testing James Bond-like gadgets, was cut for pacing.[20] On February 13, 1976, co-director John Lounsbery died of a heart attack during production. Art Stevens, an animator, was then selected as the new co-director.[27]

Animation

After the commercial success of The Aristocats (1970), then-vice president Ron Miller pledged that new animators should be hired to ensure "a continuity of quality Disney animated films for another generation."[28] Eric Larson, one of the "Nine Old Men" animators, scouted for potential artists who were studying at art schools and colleges throughout the United States. More than 60 artists were brought into the training program.[28] Then, the selected trainees were to create a black-and-white animation test, which were reviewed at the end of the month. The process would continue for several months, in which the few finalists were first employed as in-betweeners working only on nights and weekends.[29] By 1977, more than 25 artists were hired during the training program.[30] Among those selected were Glen Keane, Ron Clements, and Andy Gaskill, all of whom would play crucial roles in the Disney Renaissance.[31] Because of this, The Rescuers was the first collaboration between the newly recruited trainees and the senior animators.[30] It would also mark the last joint effort by Milt Kahl, Ollie Johnston, and Frank Thomas, and the first Disney film Don Bluth had worked on as a directing animator, instead of as an assistant animator.[26]

Ever since One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), animation for theatrical Disney animated films had been done by xerography, which had only been able to produce black outlines. By the time The Rescuers was in production, the technology had been improved for the cel artists to use a medium-grey toner in order to create a softer-looking line.[32]

Music

| The Rescuers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album Vinyl LP by | ||||

| Released | 1977 | |||

| Recorded | 1974–1977 | |||

| Label | Disneyland | |||

| Producer | Artie Butler | |||

| Walt Disney Animation Studios chronology | ||||

| ||||

Sammy Fain was first hired as a lyricist and wrote two original songs "Swamp Volunteers March" and "The Rescuers Aid Society". Meanwhile, the filmmakers had listened to an unproduced musical composed by the songwriting team of Carol Connors and Ayn Robbins.[23] Both women had first met each other in 1973 on a double date. Before then, Connors had co-composed and sang successful songs such as "To Know Him Is to Love Him" and "Hey Little Cobra" with the Teddy Bears. Meanwhile, Robbins worked as a personal secretary to actors George Kennedy and Eva Gabor and wrote unpublished poetry.[33]

Desiring more contemporary songs for the film, Reitherman called Connors and Robbins into his office and shown them storyboards of Bernard and Bianca flying on Orville. Connors and Robbins then composed "Tomorrow Is Another Day" to accompany the scene. They later composed the symphonic piece "The Journey" to play during the opening titles.[34] Near the end of the film's production, Reitherman asked artist Mel Shaw to illustrate pastel sketches to accompany the music. Shaw agreed and was assisted by Burny Mattinson.[35]

Connors and Robbins wrote another song "The Need To Be Loved", but Reitherman preferred Fain's song "Someone's Waiting for You". He nevertheless asked both women to compose new lyrics for the songs. They also recomposed a new version of the "Rescuers Aid Society" song.[34] Most of the songs they had written for the film were performed by Shelby Flint.[36] Also, for the first time since Bambi (1942), all the most prominent songs were sung as part of a narrative, as opposed to by the film's characters as in most Disney animated films.

Describing their collaborative process, Robbins noted "...Carol plays the piano and I play the pencil." During production, both women were nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Gonna Fly Now" from Rocky (1976) with Bill Conti.[36]

Songs

Original songs performed in the film include:

| No. | Title | Performer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Journey" | Shelby Flint | |

| 2. | "Rescue Aid Society" | Robie Lester, Bob Newhart, Bernard Fox & the Disney Studio Chorus | |

| 3. | "Tomorrow is Another Day" | Shelby Flint | |

| 4. | "Someone's Waiting for You" | Shelby Flint | |

| 5. | "Tomorrow is Another Day (Reprise)" | Shelby Flint |

Songs heard in the film but not released on the soundtrack include:

- "Faith is a Bluebird" – Although not an actual song, it is a poem recited by Rufus and partially by Penny in a flashback the old cat has to when he last saw the small orphan girl, and comforted her through the poem, about having faith. The titular bluebird that appears in this sequence originally appeared in Alice in Wonderland (1951).

- "The U.S. Air Force" – Serves as the leitmotif for Orville.

- "For Penny's a Jolly Good Fellow" – Sung by the orphan children at the end of the film, as a variation of the song "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow".

Release

Original theatrical run

On June 19, 1977, The Rescuers premiered at the AFI Silver Theatre in Washington, D.C.,[37] and was accompanied with the live-action nature documentary film, A Tale of Two Critters (1977).[38] By January 1979, the film had earned $15 million in distributor rentals from the United States and Canada,[39] achieving the highest-gross for an animated film during its initial release.[40]

The film was the highest-grossing film in France in 1977, out-grossing Star Wars and The Spy Who Loved Me.[40] It received admissions of 7.2 million in France generating film rentals of around $6 million.[41][42] The film also became the highest-grossing film in West Germany for 1977,[43] earning $6 million during its first 20 days of release.[40] Altogether, it received admissions of 10.3 million in Germany generating rentals of almost $12 million.[44][42] During its release, it earned $48–50 million in worldwide gross rentals at the box office.[45][5]

Re-releases

The Rescuers was re-released in 1983 and 1989.[18] During its 1983 re-release, the film was accompanied with the new Mickey Mouse featurette, Mickey's Christmas Carol, which marked the character's first theatrical appearance after a 30-year absence. The film grossed $21 million domestically.[46] In 1989, the film earned $21.2 million domestically.[47] The film's total lifetime domestic gross is $71.2 million,[48] and its total lifetime worldwide gross is $169 million.[1]

Marketing

To tie in with the film's 25th anniversary, The Rescuers debuted in the Walt Disney Classics Collection line in 2002, with three different figures featuring three of the film's characters, as well as the opening title scroll. The three figures were sculpted by Dusty Horner and they were: Brave Bianca, featuring Miss Bianca the heroine and priced at $75,[49] Bold Bernard, featuring hero Bernard, priced also at $75[50] and Evinrude Base, featuring Evinrude the dragonfly and priced at $85.[49] The title scroll featuring the film's name, The Rescuers, and from the opening song sequence, "The Journey," was priced at $30. All figures were retired in March 2005, except for the opening title scroll which was suspended in December 2012.[49]

The Rescuers was the inspiration for another Walt Disney Classics Collection figure in 2003. Ken Melton was the sculptor of Teddy Goes With Me, My Dear, a limited-edition, 8-inch sculpture featuring the evil Madame Medusa, the orphan girl Penny, her teddy bear "Teddy" and the Devil's Eye diamond. Exactly 1,977 of these sculptures were made, in reference to the film's release year, 1977. The sculpture was priced at $299 and instantly declared retired in 2003.[50]

In November 2008, a sixth sculpture inspired by the film was released. Made with pewter and resin, Cleared For Take Off introduced the character of Orville into the collection and featured Bernard and Bianca a second time. The piece, inspired by Orville's take-off scene in the film, was sculpted by Ruben Procopio.[51]

Home media

The Rescuers premiered on VHS and LaserDisc on September 18, 1992 as part of the Walt Disney Classics series. The release went into moratorium on April 30, 1993.[52] It was re-released on VHS as part of the Walt Disney Masterpiece Collection on January 5, 1999, but due to a scandal was recalled three days later and reissued on March 23, 1999.

The Rescuers was released on DVD on May 20, 2003, as a standard edition, which was discontinued in November 2011.[citation needed]

On August 21, 2012, a 35th-anniversary edition of The Rescuers was released on Blu-ray alongside its sequel in a "2-Movie Collection".[53][54]

Nudity scandal

On January 8, 1999, three days after the film's second release on home video, The Walt Disney Company announced a recall of about 3.4 million copies of the videotapes because there was a blurry image of a topless woman in the background of a scene.[55][56][57][58]

The image appears twice in non-consecutive frames during the scene in which Miss Bianca and Bernard are flying on Orville's back through New York City. The two images could not be seen in ordinary viewing because the film runs too fast—at 24 frames per second.[59]

On January 10, 1999, two days after the recall was announced, the London newspaper The Independent reported:

A Disney spokeswoman said that the images in The Rescuers were placed in the film during post-production, but she declined to say what they were or who placed them... The company said the aim of the recall was to keep its promise to families that they can trust and rely on the Disney brand to provide the best in family entertainment.[60]

The Rescuers home video was reissued on March 23, 1999, with the nudity edited and blocked out.[citation needed]

Reception

The Rescuers was said to be Disney's greatest film since Mary Poppins (1964), and seemed to signal a new golden age for Disney animation.[61] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times praised the film as "the best feature-length animated film from Disney in a decade or more—the funniest, the most inventive, the least self-conscious, the most coherent, and moving from start to finish, and probably most important of all, it is also the most touching in that unique way fantasy has of carrying vibrations of real life and real feelings."[62] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post wrote the film "is one of the most rousing and appealing animated features ever made by the Disney studio. The last production for several members of the original feature animation unit assembled by Walt Disney in the late '30s, the film is both a triumphant swan song and gladdening act of regeneration."[63] Dave Kehr of The Chicago Reader praised the film as "a beautifully crafted and wonderfully expressive cartoon feature," calling it "genuinely funny and touching."[64] Variety magazine wrote the film was "the best work by Disney animators in many years, restoring the craft to its former glories. In addition, it has a more adventurous approach to color and background stylization than previous Disney efforts have displayed, with a delicate pastel palette used to wide-ranging effect."[65]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that the film "doesn't belong in the same category as the great Disney cartoon features (Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs, Bambi, Fantasia) but it's a reminder of a kind of slickly cheerful, animated entertainment that has become all but extinct."[66] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four writing, "To see any Disney animated film these days is to compare it with Disney classics released 30 or 40 years ago. Judged against Pinocchio, for example. The Rescuers is lightweight, indeed. Its themes are forgettable. It's mostly an adventure story."[38] TV Guide gave the film three stars out of five, opining that The Rescuers "is a beautifully animated film that showed Disney still knew a lot about making quality children's fare even as their track record was weakening." They also praised the voice acting of the characters, and stated that the film is "a delight for children as well as adults who appreciate good animation and brisk storytelling."[67] Ellen MacKay of Common Sense Media gave the film four out of five stars, writing, "Great adventure, but too dark for preschoolers".[68]

In his book, The Disney Films, film historian Leonard Maltin referred to The Rescuers as "a breath of fresh air for everyone who had been concerned about the future of animation at Walt Disney's," praises its "humor and imagination and [that it is] expertly woven into a solid story structure ... with a delightful cast of characters." Finally, he declares the film "the most satisfying animated feature to come from the studio since 101 Dalmatians." He also briefly mentions the ease with which the film surpassed other animated films of its time.[69] The film's own animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston stated on their website that The Rescuers had been their return to a film with heart and also considered it their best film without Walt Disney.[70] The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that the film received a 79% approval rating, with an average rating of 6.5/10 based on 33 reviews. The website's consensus states: "Featuring superlative animation, off-kilter characters, and affectionate voice work by Bob Newhart and Eva Gabor, The Rescuers represents a bright spot in Disney's post-golden age."[71] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 74 out of 100 based on 8 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[72]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Original Song | "Someone's Waiting for You" Music by Sammy Fain; Lyrics by Carol Connors and Ayn Robbins |

Nominated | [73] |

| National Board of Review Awards | Special Citation | Won | [74] | |

In 2008, the American Film Institute nominated The Rescuers for its Top 10 Animated Films list.[75]

Legacy

Bernard and Bianca made appearances as meet-and-greet characters at Walt Disney World and Disneyland in the years following the original film's release. While they currently do not make regular appearances at the American parks, both continue to appear regularly at Tokyo Disney Resort.[citation needed]

Like other Disney animated characters, the characters of the film have recurring cameo appearances in the television series House of Mouse.

In the Disney Infinity video games, Medusa's Swamp Mobile was introduced as a vehicle in Disney Infinity 2.0.[76]

In the world builder video game Disney Magic Kingdoms, Bernard, Miss Bianca, Penny, Madame Medusa, and Orville appear as playable characters in the main storyline of the game, along with The Rescue Aid Society and Madame Medusa's Riverboat as attractions.[77][78][79]

Along with other Walt Disney Animation Studios characters, the main characters of the film have cameo appearances in the short film Once Upon a Studio.[80]

Related media

Comics

- Gold Key published an adaptation of the film under its Disney Comics Showcase banner[81]

- Two Comic strips adaptations were also published[82][83]

Sequel

The Rescuers was the first Disney animated film to have a sequel. After three successful theatrical releases of the original film, The Rescuers Down Under was released theatrically on November 16, 1990.

The Rescuers Down Under takes place in the Australian Outback, and involves Bernard and Bianca trying to rescue a boy named Cody and a giant golden eagle called Marahute from a greedy poacher named Percival C. McLeach. Both Bob Newhart and Eva Gabor reprised their lead roles. Since Jim Jordan, who had voiced Orville, had since died, a new character, Wilbur (Orville's brother, another albatross), was created and voiced by John Candy.

See also

- 1977 in film

- List of American films of 1977

- List of animated feature films of 1977

- List of highest-grossing animated films

- List of highest-grossing films in France

- List of Walt Disney Pictures films

- List of Disney theatrical animated feature films

References

- ^ a b D'Alessandro, Anthony (October 27, 2003). "Cartoon Coffers – Top-Grossing Disney Animated Features at the Worldwide B.O." Variety. p. 6. Archived from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2021 – via TheFreeLibrary.com.

- ^ a b c Ghez 2019, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Korkis, Jim (January 19, 2022). "Remembering the Rescuers". Mouse Planet. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022.

- ^ Koenig 1997, pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b "Film Reviews: The Rescuers". Variety. June 15, 1977. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ Koenig 1997, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Koenig 1997, p. 155.

- ^ a b Solomon 2016, p. 336.

- ^ Beck, Jerry (August 15, 2011). "Lost Louis Prima Disney Song". Cartoon Brew. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Solomon 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Rogers, Tom (February 24, 1974). "Floyd Huddleston Turns 'Love' Into Oscar Bid". The Tennessean. p. 8. Retrieved January 28, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Knowles, Rebecca; Bunyan, Dan (2002). "Animal Heroes". Disney: The Ultimate Visual Guide. Dorling Kindersley. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-789488-62-6.

- ^ a b Ghez 2019, p. 51.

- ^ Doty, Meriah (February 10, 2015). "Cruella de Vil's Comeback That Wasn't: See Long-Lost Sketches of Iconic Villain in 'The Rescuers' (Exclusive)". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ a b Beck, Jerry (2005). The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-556525-91-9. Retrieved February 28, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Canemaker 2001, p. 156.

- ^ "Madame Medusa". disney.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- ^ a b "The Rescuers DVD Fun Facts". disney.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2009. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- ^ Johnston, Ollie; Thomas, Frank (1993). "The Rescuers". The Disney Villain. Disney Editions. pp. 156–163. ISBN 978-1-562-82792-2.

- ^ a b Thomas & Johnston 1995, p. 373.

- ^ Koenig 1997, p. 154.

- ^ "Obituaries: James MacDonald". Variety. February 17, 1991. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ a b Koenig 1997, p. 156.

- ^ Thomas & Johnston 1995, p. 401.

- ^ Thomas & Johnston 1995, p. 398.

- ^ a b Thomas, Bob (1991). "Carrying on the Tradition". Disney's Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Beauty and the Beast. New York: Hyperion. pp. 111–112. ISBN 1-56282-899-1.

- ^ Canemaker 2001, pp. 260–261.

- ^ a b Culhane, John (August 1, 1976). "The Old Disney Magic". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Canemaker 2001, pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b Canemaker 2001, p. 79.

- ^ Finch, Christopher (1988). "Chapter 9: The End of an Era". The Art of Walt Disney: From Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdoms (New Concise ed.). Portland House. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-517664-74-2.

- ^ Deja, Andreas (May 20, 2014). "Deja View: Xerox". Deja View. Retrieved February 28, 2015 – via Blogger.

- ^ "Song Team Debuts". Playground Daily News. July 28, 1977. p. 20. Retrieved October 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Koenig 1997, p. 157.

- ^ Ghez 2019, p. 138.

- ^ a b Harada, Wayne (May 30, 1977). "It's a "Rocky" road to stardom, says Oscar-losing lyricist". The Honolulu Advertiser. p. D-6. Retrieved October 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Culhane, John (June 1977). "The Last of the 'Nine Old Men'". American Film. pp. 10–16.

- ^ a b Siskel, Gene (July 6, 1977). "Orphan, teddy bear rescue Disney film". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 6. Retrieved October 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "All-Time Film Rental Champs". Variety. January 3, 1979. p. 54. Retrieved January 21, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Fleener, Charles J. (January 3, 1979). "Contrasting 'Sells' in Titles, U.S. Against Hispanic Lands". Variety. p. 52. Retrieved January 21, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Box office for 1977". Box Office Story.

- ^ a b "New Disney World High". Variety. October 18, 1978. p. 4.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (July 28, 1978). "Disney Incubating New Artists". The New York Times. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ "Top 100 Deutschland (1957–2022)". Inside Kino (in German). Retrieved March 15, 2018. (Search: Bernard & Bianca - The Mouse Police)

- ^ King, Susan (June 22, 2012). "Disney's animated classic 'The Rescuers' marks 35th anniversary". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ "The Rescuers (1983 re-release)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ "The Rescuers (1989 re-release)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ "The Rescuers (1977)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ a b c "The Rescuers". Secondary Price Guide. Archived from the original on November 10, 2006. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- ^ a b "The Rescuers". Secondary Price Guide. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- ^ "2008 Limited Edition-Orville with Bernard & Bianca". WDCC Duckman. Archived from the original on December 7, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ^ Stevens, Mary (September 18, 1992). "'Rescuers' Leads Classic Kid Stuff". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ Burger, Dennis. "The Rescuers Slated for 2012 Blu-ray Release! (Along with Over 30 Other Disney Flicks)". Technologytell. www.technologytell.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- ^ Katz, John (February 3, 2012). "Disney Teases 2012 Blu-ray Slate". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ Mikkelson, David (January 13, 1999). "Photographic images of a topless woman can be spotted in The Rescuers". Snopes. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- ^ Davies, Jonathan (January 11, 1999). "Dis Calls in 'Rescuers' After Nude Images Found". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Howell, Peter (January 13, 1999). "Disney Knows the Net Never Blinks". The Toronto Star.

- ^ Miller, D.M. (2001). What Would Walt Do?: An Insider's Story About the Design and Construction of Walt Disney World. Writers Club Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-595-17203-0.

- ^ White, Michael (January 8, 1999). "Disney Recalls 'The Rescuers' Video". Associated Press.

- ^ "Disney recalls "sabotaged" video". The Independent (London). October 23, 2011. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ Cawley, John. "The Rescuers". The Animated Films of Don Bluth. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved April 12, 2007 – via Cataroo.com.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (July 3, 1977). "Animation: the Real Thing at Disney". Los Angeles Times. pp. 1, 33, 35–36. Retrieved October 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (June 24, 1977). "The Disney Legacy To the Rescue!". The Washington Post. p. B1. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (May 24, 1985). "The Rescuers". The Chicago Reader. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ^ "Film Reviews: The Rescuers". Variety. June 15, 1977. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (July 7, 1977). "Disney's 'Rescuers,' Cheerful Animation". The New York Times. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ "The Rescuers Reviews". TV Guide. September 3, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ^ Ellen MacKay (July 15, 2003). "The Rescuers – Movie Review". Common Sense Media. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (2000). The Disney Films. New York: Disney Editions. p. 265. ISBN 0-7868-8527-0.

- ^ "Feature Films". Frank and Ollie. Archived from the original on November 21, 2005. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- ^ "The Rescuers (1977)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "The Rescuers (1977): Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ "The 50th Academy Awards (1978) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ "1977 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Mike Futter (September 24, 2014). "Disney Infinity 2.0 - Character And Power Disc Checklist". GameInformer. Archived from the original on September 27, 2014.

- ^ "Update 59: The Rescuers (Part 1) | Livestream". YouTube. May 27, 2022.

- ^ "Update 60: The Rescuers Part 2 & Up | Livestream". YouTube. July 8, 2022.

- ^ "Update 64: DuckTales & The Rescuers (Part 3) + Tower Event | Event Walkthrough". YouTube. November 11, 2022.

- ^ Reif, Alex (October 16, 2023). "Disney's "Once Upon a Studio" – List of Characters in Order of Appearance". Laughing Place.

- ^ "Search results (38 items) | I.N.D.U.C.K.S."

- ^ "The Rescuers (ZT 094) | I.N.D.U.C.K.S."

- ^ https://coa.inducks.org/story.php?c=ZT+117 [bare URL]

Bibliography

- Canemaker, John (2001). Walt Disney's Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation. New York: Disney Editions. ISBN 978-0-7868-6496-6.

- Deja, Andreas (2015). The Nine Old Men: Lessons, Techniques, and Inspiration from Disney's Great Animators. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-1350-1586-2.

- Ghez, Didier (2019). They Drew as They Pleased Vol. 5: The Hidden Art of Disney's Early Renaissance. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-7972-0410-9.

- Koenig, David (1997). "The Rescuers". Mouse Under Glass: Secrets of Disney Animation & Theme Parks. Irvine, California: Bonaventure Press. pp. 153–161. ISBN 978-0-9640-6051-7.

- Solomon, Charles (2016). "Vance Gerry (1929–2005)". In Ghez, Didier (ed.). Walt's People: Volume 5 — Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him. Theme Park Press. ISBN 978-1-6839-0011-5.

- Solomon, Charles (2008). Disney Lost and Found: Exploring the Hidden Artwork from Never-Produced Animation. New York: Disney Editions. ISBN 978-1-4231-1601-1.

- Thomas, Frank; Johnston, Ollie (1995) [1981]. Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life. Disney Publishing Worldwide. ISBN 0-7868-6070-7.

External links

- 1977 films

- 1970s adventure comedy-drama films

- 1970s American animated films

- 1970s buddy comedy-drama films

- 1970s children's animated films

- 1970s children's fantasy films

- 1970s coming-of-age films

- 1977 crime drama films

- 1970s crime comedy films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s fantasy adventure films

- 1977 animated films

- 1977 children's films

- 1977 comedy-drama films

- American adventure comedy-drama films

- American buddy comedy-drama films

- Animated buddy films

- American children's animated adventure films

- American children's animated comedy films

- American children's animated drama films

- American children's animated fantasy films

- American coming-of-age films

- American fantasy adventure films

- Animated coming-of-age films

- Animated duos

- Animated film controversies

- Animated films about birds

- Animated films about cats

- Animated films about crocodilians

- Animated films about mice

- Animated films about orphans

- Animated films about talking animals

- Animated films based on children's books

- Animated films set in Louisiana

- Animated films set in New York City

- Disney controversies

- Films based on works by Margery Sharp

- Films about child abduction in the United States

- Films about the United Nations

- Films based on multiple works of a series

- Films directed by John Lounsbery

- Films directed by Wolfgang Reitherman

- Films directed by Art Stevens

- Films produced by Ron W. Miller

- Films with screenplays by Ken Anderson

- Films with screenplays by Larry Clemmons

- Films with screenplays by Vance Gerry

- Films with screenplays by Burny Mattinson

- Obscenity controversies in film

- Obscenity controversies in animation

- The Rescuers

- Southern Gothic films

- Walt Disney Animation Studios films

- English-language comedy-drama films

- English-language crime drama films

- English-language crime comedy films

- English-language fantasy adventure films

- English-language adventure comedy-drama films

- English-language buddy comedy-drama films

- Films with screenplays by Frank Thomas

- Films with screenplays by David Michener

- Films with screenplays by Ted Berman