Reform Club

| Reform Club | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Italian Renaissance |

| Address | 104 Pall Mall London, SW1 |

| Coordinates | 51°30′24″N 0°08′00″W / 51.50667°N 0.13333°W |

| Groundbreaking | 1837 |

| Completed | 1841 |

| Landlord | Crown Estate Commissioners |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Sir Charles Barry |

| Civil engineer | |

| Main contractor | Grissell & Peto |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Reform Club is a private members' club, owned and controlled by its members, on the south side of Pall Mall in central London, England. As with all of London's original gentlemen's clubs, it had an all-male membership for decades, but it was one of the first all-male clubs to change its rules to include the admission of women on equal terms in 1981. Since its foundation in 1836, the Reform Club has been the traditional home for those committed to progressive political ideas, with its membership initially consisting of Radicals and Whigs. However, it is no longer associated with any particular political party, and it now serves a purely social function.

The Reform Club currently enjoys extensive reciprocity with similar clubs around the world. It attracts a significant number of foreign members, such as diplomats accredited to the Court of St James's. Of the current membership of around 2,700, some 500 are "overseas members", and over 400 are women.[1]

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]The club was founded by Edward Ellice, Member of Parliament (MP) for Coventry and Whig Whip, whose riches came from the Hudson's Bay Company, but whose zeal was chiefly devoted to securing the passage of the Reform Act 1832. The club held its first meeting at No. 104 Pall Mall on 5 May 1836.[2]

This new club, for members of both Houses of Parliament, was intended to be a forum for the radical ideas which the First Reform Bill represented: its purpose was to promote "the social intercourse of the reformer of the United Kingdom".[3]

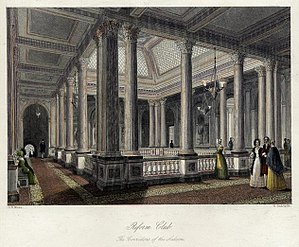

The Reform Club's building was designed by renowned architect Sir Charles Barry[4] and contracted to builders Grissell & Peto. The new club was built on palatial lines, the design being based on the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, and its Saloon in particular is regarded as the finest of all London's clubs. It was officially opened on 1 March 1841.[5] Facilities provided included a library which, following extensive donations from members, grew to contain over 85,000 books.[6]

20th century

[edit]

After the Second World War and with the old Liberal Party's further decline, the club increasingly drew its membership from civil servants.[7] The club continued to attract a comprehensive list of guest speakers including Government Ministers Nick Clegg and Theresa May (2011), Archbishop John Sentamu (2012), and Ambassador Liu Xiaoming (2013).[8]

Literary associations

[edit]Besides having had many distinguished members from the literary world, including William Makepeace Thackeray and Arnold Bennett, the Reform played a role in some significant events, such as the feud between Oscar Wilde's friend and literary executor Robbie Ross and Wilde's ex-lover Lord Alfred Douglas. In 1913, after discovering that Lord Alfred had taken lodgings in the same house as himself with a view to stealing his papers, Ross sought refuge at the club, from where he wrote to Edmund Gosse, saying that he felt obliged to return to his rooms "with firearms".[9]

Harold Owen, the brother of Wilfred Owen, called on Siegfried Sassoon at the Reform after Wilfred's death.[10] Sassoon wrote a poem entitled "Lines Written at the Reform Club", which was printed for members at Christmas 1920.[11]

Appearances in popular culture and literature

[edit]Books

[edit]The Reform Club appears in Anthony Trollope's 1867 novel Phineas Finn. This eponymous main character becomes a member of the club and there acquaints Liberal members of the House of Commons, who arrange to get him elected to an Irish parliamentary borough. The book is one of the political novels in the Palliser series. The political events it describes are a fictionalized account of the build-up to the Second Reform Act, passed in 1867, which effectively extended the franchise to the working classes.[12]

The club appears in Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days, published in 1872, as a novel in 1873. The protagonist, Phileas Fogg, is a member of the Reform Club. He sets out to circumnavigate the world on a bet from his fellow members, beginning and ending at the club.[13]

The Reform Club was used as a meeting place for MI6 operatives in Part 3, Chapter 1, p. 83ff of Graham Greene's spy novel The Human Factor (1978, Avon Books, ISBN 0-380-41491-0).[14]

The Reform Club and its Victorian era celebrity chef Alexis Soyer play pivotal roles in MJ Carter's mystery novel The Devil's Feast (2016, Fig Tree, ISBN 978-0-241-14636-1).[15]

Films and television

[edit]Comedian and travel writer Michael Palin began and ended his televised 1989 journey around the world in 80 days at the Reform Club, following his fictional predecessor. Palin was not permitted to enter the building to complete his journey, as had been his intention, so his trip ended on the steps outside. Palin later explained that he had been refused entry not because he was not wearing a tie but because the club claimed it would 'disturb the members'.[16]

Victorian publisher Norman Warne is depicted visiting the Reform Club in the 2006 film Miss Potter.[17] The club has been used as a location in a number of other films, including the fencing scene in the 2002 James Bond movie Die Another Day, The Quiller Memorandum (1966), The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970), Lindsay Anderson's O Lucky Man! (1973), The Avengers (1998), Nicholas Nickleby (2002), 1408 (2007), Quantum of Solace (2008), Sherlock Holmes (2009), Paddington (2014), and Christopher Nolan's Tenet (2020).[18]

The club was used in Chris Van Dusen's television series Bridgerton as a filming location.[19]

Photoshoot

[edit]The Reform Club was the location of a photo shoot featuring Paula Yates for the 1979 summer issue of Penthouse.[20]

Podcasts

[edit]In The Magnus Archives, the Reform Club was the possible location of Jurgen Leitner's library, and had secret underground tunnels.[21]

Notable members

[edit]- John Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair

- Donald Adamson

- H. H. Asquith

- Sir David Attenborough

- William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp

- Hilaire Belloc

- Arnold Bennett

- William Beveridge

- Stewart Binns

- Rt Hon Charles Booth

- Dame Margaret Booth

- Baroness Boothroyd

- Mihir Bose

- John Bright

- Henry Brougham

- Michael Brown, former Conservative MP

- Guy Burgess

- Donald Cameron of Lochiel

- Sir Menzies Campbell

- Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman

- Samuel Carter

- Joseph Chamberlain

- Andrew Carnegie

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

- Sir John Cassels

- Sir Winston Churchill, who resigned in 1913 in protest at the blackballing of a friend, Baron de Forest

- Richard Cobden

- Albert Cohen

- Professor Martin Daunton

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

- Queen Camilla

- Baroness Dean of Thornton-le-Fylde

- Sir Charles Dilke

- John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham

- Edward Ellice

- Lord Falconer

- Garret FitzGerald

- Edward Morgan Forster

- William Ewart Gladstone

- Baroness Greengross

- Sir William Harcourt

- Lord Hattersley

- Friedrich Hayek

- Nick Hewer

- Barbara Hosking

- Sir Michael Howard

- Sir Bernard Ingham

- Sir Henry Irving

- Henry James

- Sir John Jardine

- Lord Jenkins of Hillhead

- William, Earl Jowitt

- Alan Lascelles

- Ruth Lea

- Roger Liddle

- David Lloyd George, who resigned with Churchill over Baron de Forest's blackballing

- Professor Sir Ravinder Maini

- Dame Mary Marsh

- Professor Javier Martín-Torres

- José Guilherme Merquior

- James Moir

- James Montgomrey, a founding member

- Lord Morgan

- Sir Derek Morris

- Baroness Nicholson

- Lord Noel-Buxton

- Daniel O'Connell

- Barry Edward O'Meara

- David Omand

- Viscount Palmerston

- Dame Stella Rimington

- Bertram Fletcher Robinson

- Sir John Richard Robinson

- Oliver Robinson, 2nd Marquess of Ripon

- Curtis Roosevelt

- Brian Roper

- Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery

- Viscount Runciman

- Lord John Russell

- Siegfried Sassoon

- Paul Scofield

- Viscount Simon

- George Smith

- Sir Martin Sorrell

- Very Rev Victor Stock

- Sir Edward Sullivan

- Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex

- Professor Alan M. Taylor

- Dame Kiri Te Kanawa

- William Makepeace Thackeray

- Caroline Thomson

- William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

- Jeremy Thorpe

- Sir David Walker

- Chaim Weizmann

- H. G. Wells

- Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster

- Dame Jo Williams

- Tony Wright, former Labour MP

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Twells, Bob. "Reform Club". www.reformclub.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Fagan, Louis (1887). The Reform club: its founders and architect. Bernard Quaritch. p. 34.

- ^ Fagan 1887, p. 36. 1887.

- ^ "Pall Mall; Clubland Old and New London: Volume 4 (pp. 140–164)". british-history.ac.uk. 22 June 2003. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ "175 Years of the Reform Clubhouse 1841-2016". The Reform Club. p. 5. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "Information" (PDF). The Reform Club. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ Walker, Tim (18 October 2011). "Polly Toynbee's man makes a meal of his expenses". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ "Talking about "Reform" at the Reform Club: H.E. Ambassador Liu Xiaoming Delivers A Speech at the British Reform Club". 25 November 2013. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ Maureen Borland, Wilde's Devoted Friend: a Life of Robert Ross (1990), p. 201.

- ^ Christian Major, "Sassoon's London: the Reform Club", Siegfried's Journal, no 12 (July 2007), pp. 5–13.

- ^ Russell Burlingham & Roger Billis, Reformed Characters: The Reform Club in History and Literature (2005), p. 34.

- ^ Trollope, Anthony (1867). "Chapter 25: Mr. Turnbull's Carriage Stops the Way". St. Paul's. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "Around the World in Eighty Days". Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "The Human Factor by Graham Greene". Greg Goode. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "The Devil's Feast by M. J. Carter". Crime Review. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "Vanity Fair's Michael Palin: 'Today Becky Sharp would be on Love Island – or working as President Trump's press secretary'". Radio Times. 2 September 2018. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "Miss Potter Film Locations". Almost Ginger. 22 March 2021. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "Tenet at the Reform Club". Screen IT. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "The glamorous country houses and bucolic gardens that bring Regency London to life in Bridgerton". Tatler. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ The Milwaukee Journal – 23 July 1979.

- ^ Old Passages Archived 26 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine The Magnus Archives (Podcast). Rusty Quill. 8 September 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- The Reform Club Library: A Retrospect, 1841-1991 (London: Reform Club, 1991).

- Burlingham, Russell; Billis, Roger (2005). Reformed Characters. The Reform Club in History and Literature. An Anthology with Commentary. London: Reform Club.

- J. Mordaunt Crook, The Reform Club (London: Reform Club, 1973)

- Escott, T. H. S. (1914). Club Makers and Club Members. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Fagan, Louis (1887). The Reform Club 1836–1886: Its Founders and its Architect. London: Reform Club.

- Lejeune, Anthony; Lewis, Malcolm (1979). The Gentlemen's Clubs of London. London: Wh Smith Pub. ISBN 0-8317-3800-6.

- Lejeune, Anthony (2012). The Gentlemen's Clubs of London. London: Stacey International. ISBN 978-1-906768-20-1.

- Mordaunt Crook, J. (1973). The Reform Club. London: Reform Club.

- Sharpe, Michael (1996). The Political Committee of the Reform Club. London: Reform Club. ISBN 0-9503053-2-4.

- Thévoz, Seth Alexander (2018). Club Government: How the Early Victorian World was Ruled from London Clubs. London: I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-78453-818-7.

- Thévoz, Seth Alexander (2022). Behind Closed Doors: The Secret Life of London Private Members' Clubs. London: Robinson/Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-47214-646-5.

- Urbach, Peter (1999). The Reform Club: Some Twentieth Century Members – A Photographic Collection. London: Reform Club.

- Van Leeuwen, Thomas A P (2020) [2017]. The Magic Stove: Barry, Soyer and The Reform Club or How a Great Chef Helped to Create a Great Building. Amsterdam/Paris: Les Editions du Malentendu/ Jap Sam Books. ISBN 978-90-826690-0-8.

- Woodbridge, George (1978). The Reform Club 1836–1978: A History from the Club's Records. London: Clearwater. ISBN 0-9503053-1-6.

External links

[edit]- Reform Club website

- Survey of London's entry on the Club

- "The Reform Club: Architecture and the Birth of Popular Government", lecture by Peter Marsh and Paul Vonberg at Gresham College, 25 September 2007 (available for MP3 and MP4 download)

- Reform Club library pamphlets

- Mary Evans Picture Library – The Club's collection of caricatures

- CBC.CA Paul Kennedy's audio tour of the Club, broadcast in February 2011