The Radha Krsna Temple (album)

| The Radha Krsna Temple | |

|---|---|

| |

| Studio album by | |

| Released | 21 May 1971 |

| Recorded | July 1969, January–March 1970 |

| Studio | EMI, Apple and Trident, London |

| Genre | Indian devotional music |

| Length | 42:44 |

| Label | Apple |

| Producer | George Harrison |

| Alternative cover | |

The 1991 release Chant and Be Happy! | |

The Radha Krsna Temple is a 1971 album of Hindu devotional songs recorded by the UK branch of the Hare Krishna movement – more formally, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) – who received the artist credit of "Radha Krishna Temple (London)". The album was produced by George Harrison and released on the Beatles' Apple record label. It compiles two hit singles, "Hare Krishna Mantra" and "Govinda", with other Sanskrit-worded mantras and prayers that the Temple devotees recorded with Harrison from July 1969 onwards.

The recordings reflected Harrison's commitment to the Gaudiya Vaishnava teachings of the movement's leader, A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, who had sent devotees from San Francisco to London in 1968. The success of the Temple's first single, "Hare Krishna Mantra", helped popularise the Hare Krishna movement in the West, and inspired Harrison's more overtly religious songs on his 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass. Among the Temple members, former jazz musician and future ISKCON leader Mukunda Goswami provided the musical arrangements on the recordings.

After its initial release, the album was reissued on the Spiritual Sky label and by Prabhupada's Bhaktivedanta Book Trust. For these releases, the album was retitled Goddess of Fortune and then, with added dialogue from a conversation between Prabhupada, Harrison and John Lennon in 1969, Chant and Be Happy! Apple officially reissued The Radha Krsna Temple on CD in 1993, and again in 2010, with the addition of two bonus tracks.

Background

[edit]

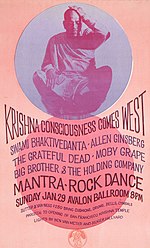

In 1968, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, founder and acharya (leader) of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), sent six of his devotees to London to establish a new centre there, the Radha Krishna Temple, and so expand on the success of ISKCON's temples in New York and San Francisco.[1] The group was led by Mukunda Das, formerly a pianist with jazz saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, and Shyamsundar Das.[2] With the acharya's blessing, they decided to seek out George Harrison of the Beatles, whose interest in Hindu philosophy, meditation and Indian classical music had done much to promote these causes among Western youth.[3] In December 1968, Shyamsundar met Harrison at the Beatles' Apple Corps headquarters in central London,[4] after which Harrison began visiting the devotees at their warehouse accommodation in Covent Garden.[5]

Harrison had first experienced kirtan, or communal chanting, while in the Indian city of Vrindavan with Ravi Shankar, in 1966.[6] Harrison was inspired by the devotees' music-making, whereby mantras were sung accompanied by instrumentation such as harmonium and percussion.[7] He and John Lennon had similarly enjoyed Prabhupada's album of chants, Krishna Consciousness.[8][9] In addition, Harrison had come to appreciate the positive properties of the Maha or Hare Krishna mantra,[10] after he had chanted it when his plane lost control during a flight back from San Francisco in August 1967.[11]

From his first visit to the devotees' warehouse, Harrison regularly played harmonium during kirtan with Shyamsundar and others. On occasions, the ensemble included synthesizer accompaniment from Billy Preston,[12] whom Harrison was producing for the Beatles' Apple record label.[13] According to author Joshua Greene, the decision to release recordings by the Radha Krishna Temple came about after one such session of kirtan, held at Harrison's Surrey home, Kinfauns.[14] Harrison telephoned the devotees the following morning, saying, "You're going to make a record", and told them to come to EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios) that same evening.[15]

"Hare Krishna Mantra" single

[edit]Via his disciples, Prabhupada had recommended that the Beatles record the Hare Krishna mantra, in order to spread the message of Krishna Consciousness to the group's wide fan base.[16] Instead, Harrison chose to produce a version by the London-based ISKCON devotees and issue it as a single on Apple Records.[17] As a song, "Hare Krishna Mantra" consists of the sixteen-word Sanskrit Maha Mantra sung over both verse and chorus:[18]

Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna

Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare

Hare Rama, Hare Rama

Rama Rama, Hare Hare

Recording

[edit]The recording for "Hare Krishna Mantra" took place at EMI Studios in July 1969,[19] shortly before a session for the Beatles' Abbey Road album. Harrison worked through a musical arrangement for the piece on guitar, with Mukunda playing piano. For the recording, Harrison decided on joint vocalists over the verses, Yamuna and Shyamsundar,[20] with the other devotees joining in on the choruses.[21] The engineer on the recording was Ken Scott.[22]

Harrison played harmonium during the initial taping, which required three takes to perfect.[23] He then added Leslie-effected electric guitar at the start of the track,[24] and also overdubbed a bass guitar part.[23] Harrison later recalled that he "had someone beat time with a pair of kartals and Indian drums",[nb 1] and that the other devotees were brought in afterwards to overdub the chorus singing and other contributions.[27]

In addition to various Temple members on mridangam and kartal, a recent American recruit played trumpet.[23] Malati (Shyamsundar's wife) sounded the closing gong,[28] after the track had built to what author Simon Leng describes as a "dervishlike climax".[24] Apple employees Mal Evans and Chris O'Dell attended this session also.[15] The latter, along with her mother, joined the backing chorus, at Shyamsundar's invitation.[29] In her 2009 autobiography, O'Dell writes of the experience of feeling "physically and spiritually changed" after singing the mantra, adding: "Chanting the words over and over again was almost hypnotic … there was a point of freedom where there was no effort at all, no criticism or judgment, just the sound generated from deep inside, like a flame that warmed us from the inside out."[30]

For the B-side, Harrison recorded the devotees singing "Prayer to the Spiritual Masters".[31] According to Prabhupada biographer Satsvarupa dasa Goswami, the lyrics offer praise to "Śrīla Prabhupāda, Lord Caitanya and His associates, and the six Gosvāmīs"[21] – Lord Caitanya being Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, the sixteenth-century avatar of the Hare Krishna movement.[16] The song again features group vocals, accompanied by harmonium, percussion and an Indian bowed string instrument known as the esraj,[32] which Shyamsundar regularly played during kirtan.[7] As for "Hare Krishna Mantra", the arrangement on "Prayer to the Spiritual Masters" was credited to Mukunda Das (as Mukunda Das Adhikary).[33]

Release

[edit]Apple Records issued the single, which was credited to "Radha Krishna Temple (London)", on 22 August 1969 in the United States (as Apple 1810) and on 29 August in the United Kingdom (as Apple 15).[34] On 28 August, Harrison joined the devotees at Apple's press launch, held in the gardens of a large property in Sydenham, south London.[35][36] Straight after the launch, Harrison drove down to the Isle of Wight to rejoin Bob Dylan,[36] who was due to make his highly publicised return to live performance at the island's music festival. On 31 August, just before Dylan took to the stage, "Hare Krishna Mantra" was played over the venue's PA.[37] Mukunda later identified this exposure, together with the song's airing during halftime at a Manchester United football game, as being indicative of how the ancient Maha Mantra "penetrated British society" via the Harrison-produced recording.[38]

In the UK, the single's picture sleeve featured a photograph of the devotees taken by Ethan Russell.[39] Harrison biographer Alan Clayson writes of the public's amusement at the appearance of the Temple devotees, dressed in orange robes and with shaved heads;[40] speaking in 2011, Mukunda recalled hearing "Hare Krishna Mantra" played on a London radio station, followed by the announcer's description: "That was a song by a group of bald-headed Americans!"[41] Clayson continues: "but thanks to George the irrepressible 'Hare Krishna Mantra' had encroached on public consciousness to a degree that Prabhupada could never have imagined in 1966."[42] In his review of the single for the NME, Derek Johnson said that Harrison had created "an Eastern Ono band", referring to Lennon's side project with Yoko Ono, the Plastic Ono Band. Johnson described the sound as "Indian gospel" and said that the track's "insistent repetition" gave it "the same insidious hypnotism as 'Give Peace A Chance'".[43]

The single was an unexpected commercial success,[32] peaking at number 12 in the UK[44] and number 15 in West Germany.[45]

The single failed to chart in America, however.[32] Shyamsundar has suggested that "some politics were involved" regarding religious groups there, and the song received little airplay as a result.[46]

The Radha Krishna Temple appeared on BBC-TV's Top of the Pops to promote the song[47] and filmed a video clip.[48] They also made many concert and festival appearances in response to the song's popularity.[42] Clayson writes of other benefits to ISKCON's cause: "there were many new converts and an even bigger increase of sympathisers who no longer regarded a line of Hare Krishna chanters down [London's] Oxford Street with sidelong scepticism …"[49] Author Peter Lavezzoli has described the success of "Hare Krishna Mantra" as "an astonishing feat" and an indication of the extent of the Beatles' cultural influence.[50][nb 2] In the Gaudiya Vaishnava faith, the international acceptance of the mantra fulfilled a prediction by Lord Chaitanya,[16] who had written: "One day, the chanting of the holy names of God will be heard in every town and village of the world."[52]

Album recording

[edit]In an interview to promote the Beatles' Abbey Road, Harrison told music journalist Ritchie Yorke that he believed fate had intervened to introduce him to Ravi Shankar, and thereby to Indian classical music and Vedic philosophy. He added that, while he was "pretending" to be a Beatle, his mission in life was to promote Indian music and Hindu spirituality in the West.[53] Harrison provided the Radha Krishna Temple with financial assistance[50] and acted as a co-signee of their more permanent accommodation[54] – at Bury Place, close to the British Museum in Bloomsbury.[55] He met Prabhupada in September 1969, at Lennon's Tittenhurst Park estate, as the new premises was being renovated.[56][57] While also producing Apple acts such as Preston and Doris Troy,[58][59] Harrison was keen to record further with the Temple devotees and release a full album of their songs. In December, he suggested they come up with further material.[60] Scott was again credited as the engineer at these later Radha Krishna Temple sessions.[22] He has spoken of the challenges of recording the participants, many of whom would not remain stationary during a take, and described the project as "absolutely fascinating".[61]

The musicians on these recordings included Harrison on guitars and bass; Temple members such as Yamuna on lead vocals; and other devotees on backing vocals, mridanga, harmonium, tambura and kartal.[62] Harrison was much impressed with Yamuna's voice and suggested she could become "a famous rock star".[63] In a 1982 discussion with Mukunda, Harrison said: "I liked the way [Yamuna] sang with conviction, and she sang ['Hare Krishna Mantra'] like she'd been singing it a lot before. It didn't sound like the first [professionally recorded] tune she'd ever sung."[64] Discussing Harrison's role in the studio, Gurudas, Yamuna's husband, has compared him with the Hare Krishna movement's leader, saying: "George was like Prabhupada, he could be a ringmaster – he could just pull everything together."[65]

"Sri Guruvastakam" and one other track on the album include Harrison playing dobro,[66] an instrument that he went on to use increasingly during the early 1970s.[67] Arrangements for all the songs on The Radha Krsna Temple were again credited to Mukunda.[68] A student in Paris at the time, and a keyboard player in his university band, Joshua Greene joined the Radha Krishna Temple over the 1969–70 holiday season,[69] taking the devotee name Yogesvara.[70] He recalls participating in sessions held at EMI[62] and Apple Studio, during which he played harmonium on "Govinda Jai Jai".[71] Whereas Harrison had limited the length of the earlier recordings to no more than four minutes, to attract maximum radio play,[72] album tracks such as "Bhaja Bhakata/Arati" and "Bhaja Hunre Mana" extended to over eight minutes.[73][nb 3]

"Govinda" single

[edit]Recording

[edit]Among the new pieces was "Govinda", a musical adaptation of what is considered to be the world's first poem,[77] consisting of Govindam prayers.[78] Gurudas described it to a reporter as a song that "comes from the Satya Yuga or Golden Era of the universe and was passed down through the ages by a chain of self-realized gurus".[79] Author Bruce Spizer writes that Harrison "went all out" with his production of the track, creating an "exciting and hypnotic arrangement".[32]

The recording session took place in January 1970,[80] at Trident Studios in central London.[27] Harrison had already created the backing track, which featured rock instrumentation such as acoustic guitar, organ, bass and drums, before the devotees' arrival. Yamuna was the sole lead vocalist. Also among those attending the session, in Greene's recollection, were Billy Preston and singers Donovan and Mary Hopkin, some of whom joined the devotees on the song's choruses.[63][nb 4] Over the introduction, Harrison overdubbed esraj, played by Shyamsundar, and lute-like oud, which was performed by Harivilas, a devotee who had recently arrived in London from Iran.[63]

Following this session, Harrison added a lead guitar part[77] and hired members of the London Philharmonic Orchestra to overdub string orchestration, harp and tubular bells onto the track.[63] The orchestral arrangement for "Govinda" was supplied by John Barham,[26] a regular Harrison collaborator,[82] and similarly dedicated to furthering Western appreciation of Indian classical music.[83]

Release

[edit]Backed with "Govinda Jai Jai", "Govinda" was issued by Apple on 6 March 1970 in Britain (as Apple 25) and 24 March in the United States (as Apple 1821).[84][85] The single made the UK top 30, peaking at number 23.[44] Apple's press officer, Derek Taylor, later recalled that his department placed print advertisements stating that "Govinda" was "the best record ever made".[27] Prabhupada first heard the recording in Los Angeles; moved to tears, he asked for it to be played every morning while ISKCON devotees offered prayers in honour of the deities.[86] In their book documenting the first 40 years of the Hare Krishna movement, Graham Dwyer and Richard Cole write that with "Hare Krishna Mantra" and "Govinda" "[becoming] hits across Europe, in Japan, in Australia, and even in Africa … the chanting of Hare Krishna had become world famous".[48] In his essay on ISKCON temple procedure, Kenneth Valpey writes of the significance of the lead singer being female – an "unthinkable" event in more traditional systems of Krishna worship, but consistent with Prabhupada's openness to having women in the role of temple priests.[87]

Coinciding with the release of "Govinda", Harrison accompanied Shyamsundar and other devotees to Paris,[88] to help establish the local ISKCON branch there.[89] Showing further support for the Hare Krishna movement,[48][90] Harrison financed the publication of Prabhupada's Krsna Book in March 1970.[91] Soon afterwards, he accommodated families from the expanding London Radha Krishna Temple at his newly purchased estate in Oxfordshire, Friar Park,[92][93] before going on to record his triple album All Things Must Pass.[94] The latter also reflected his embracing of the Temple's Gaudiya Vaishnava doctrine and Krishna Consciousness,[95] in songs such as "My Sweet Lord",[96] "Awaiting on You All"[97] and "Beware of Darkness".[98]

Album release

[edit]Yamuna told Prabhupada that Harrison was hoping to issue the devotees' album "in time for Christmas [1970]", with the title Bhaja Hunre Mana, Mana Hu Re.[99] In fact, Apple Records released The Radha Krsna Temple on 21 May 1971 in America (as Apple SKAO 3376) and 28 May in Britain (as Apple SAPCOR 18). In addition to four new songs, the album included tracks previously issued on the Radha Krishna Temple (London) singles – "Hare Krishna Mantra", "Govinda" and "Govinda Jai Jai".[68] The version of "Govinda" extended to 4:39 in duration, whereas the 1970 A-side had a running time of 3:18.[100]

Featuring a photo taken by John Kosh,[22] the album cover depicted the deities Radha and Krishna in the temple at Bury Place.[75] The LP's inner sleeve included a reproduction of a painting of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, while a photo of Prabhupada appeared on the back cover.[22] Print advertisements accompanying the US release carried text reading: "Vibrations of these mantras reveal to the receptive hearer and chanter the realm of KRSNA consciousness, joyfully experienced as a peace of self and awareness of GOD and KRSNA. These eternal sounds of love release the hearer from all contemporary barriers of time and space."[101][102]

Billboard magazine included The Radha Krsna Temple among its "4 Star" albums list on 29 May.[103] The previous week, the magazine had reported on "heavy" promotional activities being undertaken by the Dutch branch of the movement.[104] The album followed the worldwide success of Harrison's "My Sweet Lord" single, which had further popularised the Maha Mantra,[105][106] and by association the Hare Krishna movement,[95][107] through that song's incorporation of the mantra and other Sanskrit verses.[108][109] Despite this, The Radha Krsna Temple failed to chart in Britain or America, issued at a time when Apple's promotion of its artists had deteriorated[110] following Allen Klein's cutbacks within the company throughout 1970.[111][112]

Reissue

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Q | |

After an initial release on CD in 1993,[116] with liner notes provided by Derek Taylor, The Radha Krsna Temple was remastered and reissued in October 2010, as part of the Apple Box Set.[117] Taylor's essay carried the slogan "20th Anniversary of Bhaktivedanta Manor 1973–1993 – Here To Stay!",[27] referring to the Hertfordshire property that Harrison had donated to the UK branch of the Hare Krishna movement in February 1973.[118][nb 5]

Before the Apple reissues, the album was re-released as Goddess of Fortune on the Spiritual Sky label in 1973,[123] and in other editions, including through Prabhupada's Bhaktivedanta Book Trust in 1991.[124] The cover of Goddess of Fortune replaced Kosh's 1971 artwork with a photo by Clive Arrowsmith and a design credited to Peter Hawkins.[125] Another title during the early 1990s was Chant and Be Happy!,[126] a release that combined the original album with a ten-minute recording of Harrison, Lennon and Ono discussing Krishna Consciousness with Prabhupada.[127]

The 1993 Apple CD added the non-album B-side "Prayer to the Spiritual Masters" as a bonus track,[128] while the 2010 reissue also included the previously unreleased "Namaste Saraswati Devi",[117] a song written in praise of Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of knowledge, music and the arts.[129] That year, the album version of "Govinda" appeared on Apple's first-ever multi-artist compilation, Come and Get It: The Best of Apple Records.[130] This second Apple reissue was remastered by Paul Hicks and Alex Wharton, led by Abbey Road project coordinator Allan Rouse.[75]

Reviewing the 2010 remastered album, Joe Marchese of The Second Disc writes that The Radha Krsna Temple has "a spellbinding quality, and remains a fascinating artifact of a special place and time for Harrison and Apple Records".[117] In a review for AllMusic, music critic Ken Hunt writes of the devotees' eponymous album: "this reissue reinstates their ecstatic music to disc. Its slightly Westernized but appealing arrangements betray Harrison's handiwork … For a season it turned into the popular face of Hinduism."[113] In his appraisal of Harrison's solo career for Blender magazine in 2004, Paul Du Noyer included the Chant and Be Happy! version in the category "For fans only" and highlighted "Govinda Jai Jai" as the "standout track".[114]

Legacy

[edit]

Alan Clayson identifies the influence of the Radha Krishna Temple's recordings, along with the East–West musical fusion of Harrison's 1968 solo album Wonderwall Music, on Britpop bands such as Kula Shaker, which he describes as "the most exotic of all the new Top-40 arrivals of the mid 1990s". In addition to incorporating the Sanskrit term Achintya-bheda-abheda in their 1996 hit "Tattva", Kula Shaker released a single in November that year, "Govinda", named after the Temple's second hit song (but in fact a cover of "Govinda Jai Jai").[131] AllMusic editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine states that Radha Krishna Temple (London)'s 1970 hit "pretty much provided the blueprint for Kula Shaker's career",[130] while David Cavanagh of Uncut wrote in 2010 that The Radha Krsna Temple "should appeal to fans of Tinariwen, not to mention lead singers of Kula Shaker".[132]

In a review of the Come and Get It compilation, Douglas Wolk of Pitchfork Media includes the Temple as an example of the Beatles' "willingness to go to bat for totally uncommercial ideas" on their short-lived record label;[133] music historian Colin Larkin similarly highlights the devotees' album among an "eccentric catalog" that included the composer John Tavener and the Modern Jazz Quartet.[134] This adventurousness, Wolk continues, provides the "really fun" aspect of the 2010 compilation, just as it "made the Beatles' own Apple releases particularly entertaining".[133] According to David Fricke of Rolling Stone, Harrison viewed the Radha Krishna Temple's presence on Top of the Pops as "one of the greatest thrills of his life". In the same 1980s interview, Harrison added: "That was more fun really than trying to make a pop hit record. It was the feeling of utilizing your skills to do some spiritual service for Krishna."[47] The track "Govinda" continues to be played every morning at ISKCON temples around the world, to greet the deities.[135]

Although Harrison's former bandmate Paul McCartney had little time for the devotees originally, according to Taylor,[136] he mentioned the Radha Krsna Temple album in a 1973 interview with Rolling Stone, describing it as "great stuff" and an example of the worthwhile projects undertaken by Apple.[137] During Mukunda's 1982 interview with Harrison, Mukunda commented that McCartney had grown more sympathetic to the movement in recent years.[138] Mukunda and Harrison also discussed Dylan's adoption of chanting and his attendance at ISKCON centres across the United States.[139]

Along with Ken Scott, Mukunda provided reminisces of the Radha Krishna Temple recordings in Martin Scorsese's 2011 documentary George Harrison: Living in the Material World.[140] In an article about that film, for The Huffington Post, Religion News Service reporter Steve Rabey refers to the devotees' album as an example of Harrison's status as a "cafeteria Hindu", while commenting that "[although] he failed to convert everyone to his beliefs, he nudged his bandmates – and his listener fans – a bit further to the East, encouraging audiences to open themselves to new (or very old) spiritual influences."[141]

Track listing

[edit]All songs are traditional and arranged by Mukunda Das Adhikary. Track titles and times per Castleman and Podrazik for original release,[68] and CD booklet for 2010 reissue.[75]

Original release

[edit]- Side one

- "Govinda" – 4:39

- "Sri Guruvastakam" – 3:07

- "Bhaja Bhakata/Arati" – 8:28

- "Hare Krsna Mantra" – 3:35

- Side two

- "Sri Isopanisad" – 4:00

- "Bhaja Hunre Mana" – 8:43

- "Govinda Jaya Jaya" – 5:58

1993 reissue

[edit]Tracks 1–7 per original release.

- Bonus track

- "Prayer to the Spiritual Masters" – 3:59

2010 remaster

[edit]Tracks 1–7 per original release, but with spelling in some titles altered.

- "Govinda" – 4:43

- "Sri Guruvastak" – 3:11

- "Bhaja Bhakata/Arotrika" – 8:25

- "Hare Krsna Mantra" – 3:34

- "Sri Isopanisad" – 4:04

- "Bhaja Hure Mana" – 8:52

- "Govinda Jai Jai" – 5:57

- Bonus tracks

- "Prayer to the Spiritual Masters" – 3:58

- "Namaste Saraswati Devi" – 4:57

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Alan White, a drummer who played on several Apple projects over 1969–71,[25] is credited on the recording.[26]

- ^ Acknowledging the difficulty of marketing the single to the public, and the demanding nature of the individual Beatles' projects, Apple press officer Derek Taylor joked in a September 1969 interview that Harrison's idea had been "to take the worst minority religious cult in England and get a top thirty record with it in ten days".[51]

- ^ The spelling of some song titles differs between the original album release and the 2010 reissue. In addition, while the debut single was titled "Hare Krishna Mantra" in 1969, it was rendered as "Hare Krsna Mantra" in both the 1971[74] and 2010 album track listings.[75] Similarly, "Govinda Jai Jai" was the wording used for that song on Radha Krishna Temple's second single, yet it subsequently appeared as "Govinda Jaya Jaya" on the album,[76] only to revert to the original spelling in 2010.[75]

- ^ According to author John Winn, the bassist and drummer on the track were most likely Klaus Voormann and Ringo Starr, respectively.[81]

- ^ Since 1981, Bhaktivedanta Manor had been facing the threat of closure as a public temple, due to frequent complaints to the local Hertsmere Borough Council regarding the level of traffic in the village of Aldenham during festival periods.[119][120] The issue was finally resolved in 1996 when the Department of the Environment granted permission for the devotees to build a road bypassing Aldenham.[121][122]

References

[edit]- ^ Dwyer & Cole, p. 30.

- ^ Greene, pp. 84, 103, 106.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 34, 36.

- ^ Tillery, p. 69.

- ^ Greene, pp. 106, 143.

- ^ Tillery, pp. 57–58, 69.

- ^ a b Greene, p. 108.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 247, 248.

- ^ Tillery, pp. 58–59, 69, 160.

- ^ Tillery, pp. 108–10.

- ^ Greene, pp. 84, 103, 145.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 267, 275–76.

- ^ Spizer, p. 340.

- ^ Greene, pp. 141–43.

- ^ a b Greene, p. 143.

- ^ a b c Tillery, p. 71.

- ^ Goswami, p. 155.

- ^ Allison, pp. 46, 122, 144.

- ^ O'Dell, p. 78.

- ^ Greene, pp. 143–44.

- ^ a b Goswami, p. 156.

- ^ a b c d Sleeve credits, The Radha Krsna Temple LP (Apple Records, 1971; produced by George Harrison).

- ^ a b c Greene, p. 144.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 58.

- ^ Rodriguez, pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b Castleman & Podrazik, p. 202.

- ^ a b c d Liner notes by Derek Taylor, The Radha Krsna Temple CD (Apple/Capitol, 1993; produced by George Harrison).

- ^ Greene, pp. 106, 144.

- ^ O'Dell, pp. 79–80.

- ^ O'Dell, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Allison, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d Spizer, p. 341.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 79.

- ^ Miles, pp. 350, 351.

- ^ Beatles timeline, Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Revolution (The Beatles' Final Years – Jan 1, 1968 to Sept 27, 1970), Emap (London, 2003), p. 114.

- ^ a b Miles, p. 351.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 273–74.

- ^ Harrison, p. 236.

- ^ Sleeve credit, "Hare Krishna Mantra" single (Apple Records, 1969; produced by George Harrison).

- ^ Clayson, pp. 267, 268.

- ^ Mukunda Goswami, in George Harrison: Living in the Material World; event occurs at 18:34–43.

- ^ a b Clayson, p. 268.

- ^ Derek Johnson, "Top Singles Reviewed by Derek Johnson", NME, 6 September 1969, p. 6.

- ^ a b "Artist: Radha Krishna Temple", Official Charts Company (retrieved 4 September 2014).

- ^ "Radha Krishna Temple, 'Hare Krishna Mantra'", offiziellecharts.de (retrieved 27 October 2022).

- ^ "George Harrison – Tribute by Hare Krishna Members", in Hare Krishna Tribute to George Harrison; event occurs at 16:58–17:06.

- ^ a b The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Dwyer & Cole, p. 31.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 268–69.

- ^ a b Lavezzoli, p. 195.

- ^ Winn, p. 324.

- ^ Greene, pp. 107, 148, 153.

- ^ Winn, pp. 323–24.

- ^ Clayson, p. 267.

- ^ Greene, pp. 148, 157–58.

- ^ Dwyer & Cole, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Tillery, pp. 71–72, 161.

- ^ Rodriguez, pp. 1, 72–73.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 424.

- ^ Greene, p. 169.

- ^ Ken Scott, in George Harrison: Living in the Material World; event occurs at 17:55–18:19.

- ^ a b Greene, p. ix.

- ^ a b c d Greene, p. 170.

- ^ Chant and Be Happy, p. 16.

- ^ "George Harrison – Tribute by Hare Krishna Members", in Hare Krishna Tribute to George Harrison; event occurs at 16:38–16:45.

- ^ Jason Kruppa, "013 George Harrison, 'My Sweet Lord'", Producing the Beatles: The Podcast, 25 April 2022 (retrieved 27 October 2022); event occurs at 8:50–9:31.

- ^ Leng, pp. 73, 108, 114.

- ^ a b c Castleman & Podrazik, p. 101.

- ^ Greene, pp. ix–x, 279.

- ^ "Interview: Yogesvara Dasa (Joshua M. Greene)", Harmonist, 19 June 2011 (retrieved 6 September 2014).

- ^ "Yogesvara Dasa Remembers George", in Hare Krishna Tribute to George Harrison; event occurs at 2:00–3:18.

- ^ Chant and Be Happy, pp. 14, 15.

- ^ Allison, p. 137.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 79, 101.

- ^ a b c d e Album credits, The Radha Krsna Temple CD (Apple/EMI, 2010; produced by George Harrison; reissue produced by Andy Davis & Mike Heatley).

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 86–87, 101.

- ^ a b Allison, p. 143.

- ^ Greene, pp. 131, 169, 171.

- ^ Greene, pp. 171, 211.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 86.

- ^ Winn, p. 368.

- ^ Andy Childs, "The History of Jackie Lomax", ZigZag, July 1974; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Leng, pp. 26–27, 39, 49–50.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Miles, pp. 371, 372.

- ^ Greene, pp. 170–71.

- ^ Kenneth Valpey, "Krishna in Mleccha Desh: ISKCON Temple Worship in Historical Perspective", in Bryant & Ekstrand, p. 52.

- ^ Doggett, p. 117.

- ^ Greene, pp. 174–75.

- ^ Allison, p. 46.

- ^ Tillery, p. 72–73, 161.

- ^ Greene, pp. 166–67.

- ^ Doggett, p. 116.

- ^ Tillery, pp. 90–91, 161.

- ^ a b Clayson, p. 295.

- ^ Leng, pp. 71, 83–84.

- ^ Allison, pp. 46, 47.

- ^ Inglis, p. 28.

- ^ Prtha Devi Dasi, "George Harrison and Srila Prabhupada" > "SP Speech to Maharaja and Maharaini and Conversations Before and After, Indore, Dec 11, 1970", Christ and Krishna (retrieved 9 September 2014).

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 87, 101.

- ^ "Advert for the album 'Radha Krsna Temple'", Apple Records (retrieved 6 September 2014).

- ^ George Harrison: Living in the Material World; event occurs at 18:28.

- ^ "Billboard Album Reviews", Billboard, 29 May 1971, p. 24 (retrieved 6 September 2014).

- ^ Bas Hageman, "Holland", Billboard, 22 May 1971, pp. 46, 48 (retrieved 6 September 2014).

- ^ Greene, pp. 181–83, 185.

- ^ Graham M. Schweig, "Krishna: The Intimate Deity", in Bryant & Ekstrand, p. 14.

- ^ Chant and Be Happy, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 186, 195.

- ^ Tillery, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Leng, p. 62.

- ^ Doggett, p. 139.

- ^ Clayson, p. 281.

- ^ a b Ken Hunt, "Radha Krishna Temple (London)/Radha Krsna Temple The Radha Krsna Temple", AllMusic (retrieved 7 September 2014).

- ^ a b Paul Du Noyer, "Back Catalogue: George Harrison", Blender, April 2004, pp. 152–53.

- ^ Tom Hibbert, "Re-releases: Radha Krishna Temple (London) The Radha Krsna Temple", Q, May 1993, p. 107.

- ^ Winn, pp. 368–69.

- ^ a b c Joe Marchese, "Review: The Apple Records Remasters, Part 3 – Esoteric to the Core", The Second Disc, 17 November 2010 (retrieved 4 September 2014).

- ^ Tillery, pp. 111, 162.

- ^ Dwyer & Cole, pp. 41–45.

- ^ "ISKCON and 8 Others v. the United Kingdom", HUDOC, 8 March 1994 (archived version retrieved 17 October 2014).

- ^ "Campaign to save the Manor", bhaktivedantamanor.co.uk (retrieved 3 March 2015).

- ^ Dwyer & Cole, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Listing: "Goddess Of Fortune – Goddess Of Fortune (Vinyl, LP, Album)", Discogs (retrieved 4 September 2014).

- ^ Listing: "Radha Krishna Temple, The – Goddess Of Fortune (CD, Album)", Discogs (retrieved 4 September 2014).

- ^ Album credits, Goddess of Fortune LP (Spiritual Sky, 1973).

- ^ Allison, pp. 122, 144.

- ^ "Radha Krsna Temple Chant and Be Happy!: Indian Devotional Songs", AllMusic (retrieved 6 November 2017).

- ^ Album credits, The Radha Krsna Temple CD (Apple/Capitol, 1993; produced by George Harrison).

- ^ Liner notes by Andy Davis, The Radha Krsna Temple CD (Apple/EMI, 2010; produced by George Harrison; reissue produced by Andy Davis & Mike Heatley).

- ^ a b Stephen Thomas Erlewine, "Various Artists Come and Get It: The Best of Apple Records", AllMusic (retrieved 19 September 2014).

- ^ Clayson, p. 439.

- ^ David Cavanagh, "The Apple Remasters", Uncut, November 2010, p. 112.

- ^ a b Douglas Wolk, "Various Artists Come and Get It: The Best of Apple Records", Pitchfork Media, 23 November 2010 (retrieved 19 September 2014).

- ^ Larkin, p. 684.

- ^ Greene, p. 171.

- ^ Doggett, p. 92.

- ^ Paul Gambaccini, "The Rolling Stone Interview: Paul McCartney", Rolling Stone, 31 January 1974; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Chant and Be Happy, p. 15.

- ^ Chant and Be Happy, p. 36.

- ^ Mukunda Goswami, in George Harrison: Living in the Material World.

- ^ Steve Rabey, "George Harrison, 'Living In The Material World'", Huffington Post, 9 October 2011 (retrieved 29 November 2014).

Sources

[edit]- Dale C. Allison Jr., The Love There That's Sleeping: The Art and Spirituality of George Harrison, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8264-1917-0).

- Edwin F. Bryant & Maria Ekstrand (eds), The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant, Columbia University Press (New York, NY, 2004; ISBN 0-231-12256-X).

- Harry Castleman & Walter J. Podrazik, All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975, Ballantine Books (New York, NY, 1976; ISBN 0-345-25680-8).

- Chant and Be Happy: The Power of Mantra Meditation, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust (Los Angeles, CA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-89213-118-1).

- Alan Clayson, George Harrison, Sanctuary (London, 2003; ISBN 1-86074-489-3).

- Peter Doggett, You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup, It Books (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8).

- Graham Dwyer & Richard J. Cole (eds), The Hare Krishna Movement: Forty Years of Chant and Change, I.B. Tauris (London, 2007; ISBN 1-84511-407-8).

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, Harrison, Rolling Stone Press/Simon & Schuster (New York, NY, 2002; ISBN 0-7432-3581-9).

- George Harrison: Living in the Material World DVD (Disc 2), Village Roadshow, 2011 (directed by Martin Scorsese; produced by Olivia Harrison, Nigel Sinclair & Martin Scorsese).

- Satsvarupa dasa Goswami, Prabhupada: He Built a House in Which the Whole World Can Live, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust (Los Angeles, CA, 1983; ISBN 0-89213-133-0).

- Joshua M. Greene, Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison, John Wiley & Sons (Hoboken, NJ, 2006; ISBN 978-0-470-12780-3).

- Hare Krishna Tribute to George Harrison DVD (ITV Productions, 2002).

- Olivia Harrison, George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Abrams (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4197-0220-4).

- Ian Inglis, The Words and Music of George Harrison, Praeger (Santa Barbara, CA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3).

- Colin Larkin, Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Volume 1: Media, Industry and Society, Continuum (London, 2003; ISBN 0-8264-6321-5).

- Peter Lavezzoli, The Dawn of Indian Music in the West, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 0-8264-2819-3).

- Simon Leng, While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison, Hal Leonard (Milwaukee, WI, 2006; ISBN 1-4234-0609-5).

- Chip Madinger & Mark Easter, Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium, 44.1 Productions (Chesterfield, MO, 2000; ISBN 0-615-11724-4).

- Barry Miles, The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years, Omnibus Press (London, 2001; ISBN 0-7119-8308-9).

- Chris O'Dell with Katherine Ketcham, Miss O'Dell: My Hard Days and Long Nights with The Beatles, The Stones, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and the Women They Loved, Touchstone (New York, NY, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4).

- Robert Rodriguez, Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980, Backbeat Books (Milwaukee, WI, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4).

- Bruce Spizer, The Beatles Solo on Apple Records, 498 Productions (New Orleans, LA, 2005; ISBN 0-9662649-5-9).

- Gary Tillery, Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison, Quest Books (Wheaton, IL, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8356-0900-5).

- John C. Winn, That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970, Three Rivers Press (New York, NY, 2009; ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9).