Peterloo Massacre

| Peterloo Massacre | |

|---|---|

A coloured print of the Peterloo Massacre | |

| Location | St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England |

| Coordinates | 53°28′36″N 02°14′45″W / 53.47667°N 2.24583°W |

| Date | 16 August 1819[1] |

| Deaths | 18 |

| Injured | 400–700 |

| Assailants | |

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Eighteen people died and 400–700 were injured when cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliamentary representation.

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, there was an acute economic slump, accompanied by chronic unemployment and harvest failure due to the Year Without a Summer, and worsened by the Corn Laws, which kept the price of bread high. At that time, only around 11 percent of adult males had the right to vote, very few of them in the industrial north of England, which was worst hit. Radicals identified parliamentary reform as the solution, and a mass campaign to petition parliament for manhood suffrage gained three-quarters of a million signatures in 1817 but was flatly rejected by the House of Commons. When a second slump occurred in early 1819, Radicals sought to mobilise huge crowds to force the government to back down. The movement was particularly strong in the north-west, where the Manchester Patriotic Union organised a mass rally in August 1819, addressed by well-known Radical orator Henry Hunt.

Shortly after the meeting began, local magistrates called on the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry to arrest Hunt and several others on the platform with him. The Yeomanry charged into the crowd, knocking down a woman and killing a child, and finally apprehended Hunt. Cheshire Magistrates' chairman William Hulton then summoned the 15th Hussars to disperse the crowd. They charged with sabres drawn, and contemporary accounts estimated that between nine and seventeen people were killed and 400 to 700 injured in the ensuing confusion. The event was first labelled the "Peterloo massacre" by the radical Manchester Observer newspaper in a bitterly ironic reference to the bloody Battle of Waterloo which had taken place four years earlier.

Historian Robert Poole has called the Peterloo Massacre "the bloodiest political event of the 19th century in English soil", and "a political earthquake in the northern powerhouse of the industrial revolution".[2] The London and national papers shared the horror felt in the Manchester region, but Peterloo's immediate effect was to cause the Tory government under Lord Liverpool to pass the Six Acts, which were aimed at suppressing any meetings for the purpose of radical reform. It also led indirectly to the foundation of The Manchester Guardian newspaper.[3] In a survey conducted by The Guardian (the modern iteration of The Manchester Guardian) in 2006, Peterloo came second to the Putney Debates as the event from radical British history that most deserved a proper monument or a memorial.

For some time, Peterloo was commemorated only by a blue plaque, criticised as being inadequate and referring only to the "dispersal by the military" of an assembly. In 2007, the city council replaced the blue plaque with a red plaque referring to "a peaceful rally" being "attacked by armed cavalry" and mentioning "15 deaths and over 600 injuries". In 2019, on the 200th anniversary of the massacre, Manchester City Council inaugurated a new Peterloo Memorial by the artist Jeremy Deller, featuring eleven concentric circles of local stone engraved with the names of the dead and the places from which the victims came.

Background

[edit]Suffrage

[edit]In 1819, Lancashire was represented by two county members of parliament (MPs) and a further twelve borough members sitting for the towns of Clitheroe, Newton, Wigan, Lancaster, Liverpool, and Preston, with a total of 17,000 voters in a county population of nearly a million. Thanks to deals by Whig and Tory parties to carve up the seats between them, most had not seen a contested election within living memory.[4]

Nationally, the so-called rotten boroughs had a hugely disproportionate influence on the membership of the Parliament of the United Kingdom compared to the size of their populations: Old Sarum in Wiltshire, with one voter, elected two MPs,[5] as did Dunwich in Suffolk, which by the early 19th century had almost completely disappeared into the sea.[6] The major urban centres of Manchester, Salford, Bolton, Blackburn, Rochdale, Ashton-under-Lyne, Oldham and Stockport had no MPs of their own, and only a few hundred county voters. By comparison, more than half of all MPs were returned by a total of just 154 owners of rotten or closed boroughs.[5] In 1816, Thomas Oldfield's The Representative History of Great Britain and Ireland; being a History of the House of Commons, and of the Counties, Cities, and Boroughs of the United Kingdom from the earliest Period claimed that of the 515 MPs for England and Wales 351 were returned by the patronage of 177 individuals and a further 16 by the direct patronage of the government: all 45 Scottish MPs owed their seats to patronage.[7] These inequalities in political representation led to calls for reform.[6][8]

Economic conditions

[edit]After the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, a brief boom in textile manufacture was followed by periods of chronic economic depression, particularly among cotton textile weavers and spinners. The cotton textile trade was concentrated in Lancashire and the wool textile trade was concentrated over the border in West and North Yorkshire.[9] Weavers who could have expected to earn 15 shillings for a six-day week in 1803, saw their wages cut to 5 shillings or even 4s 6d by 1818.[10] The industrialists, who were cutting wages without offering relief, blamed market forces generated by the aftershocks of the Napoleonic Wars.[10] Exacerbating matters were the Corn Laws, the first of which was passed in 1815, imposing a tariff on foreign grain in an effort to protect English grain producers. The cost of food rose as people were forced to buy the more expensive and lower quality British grain, and periods of famine and chronic unemployment ensued, increasing the desire for political reform both in Lancashire and in the country at large.[11][12]

Radical mass meetings in Manchester

[edit]In the winter of 1816–17 massed reform petitions were rejected by the House of Commons, the largest of them from Manchester with over 30,000 signatures.[13][14] On 10 March 1817 a crowd of 5,000 gathered in St Peter's Fields to send some of their number to march to London to petition the Prince Regent to force parliament into reform; the so-called 'blanket march', after the blankets which the protesters carried with them to sleep in on the way. After the magistrates read the Riot Act, the crowd was dispersed without injury by the King's Dragoon Guards. The ringleaders were detained for several months without charge under the emergency powers then in force, which suspended habeas corpus, the right to be either charged or released. In September 1818 three former leading Blanketeers were again arrested for allegedly urging striking weavers in Stockport to demand their political rights, 'sword in hand', and were convicted of sedition and conspiracy at Chester Assizes in April 1819.[15]

By the beginning of 1819, pressure generated by poor economic conditions was at its peak and had enhanced the appeal of political radicalism among the cotton loom weavers of south Lancashire.[9] In January 1819, a crowd of about 10,000 gathered at St Peter's Fields to hear the radical orator Henry Hunt and called on the Prince Regent to choose ministers who would repeal the Corn Laws. The meeting, conducted in the presence of the cavalry, passed off without incident, apart from the collapse of the hustings.[16][17][18]

A series of mass meetings in the Manchester region, Birmingham, and London over the next few months alarmed the government. "Your country [i.e. county] will not be tranquillised until blood shall have been shed, either by the law or the sword", the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth wrote to the Lancashire magistrates in March. Over the next few months the government worked to find a legal justification for the magistrates to send in troops to disperse a meeting when riot was expected but not actually begun. In July 1819, the magistrates wrote to Lord Sidmouth warning they thought a "general rising" was imminent, the "deep distress of the manufacturing classes" was being worked on by the "unbounded liberty of the press" and "the harangues of a few desperate demagogues" at weekly meetings. "Possessing no power to prevent the meetings" the magistrates admitted they were at a loss as to how to stem the doctrines being disseminated.[19]: 1–3 The Home Office assured them privately that in "an extreme case a magistrate may feel it incumbent upon him to act even without evidence, and to rely on Parliament for an indemnity."[20]

August meeting

[edit]Against this background, a "great assembly" was organised by the Manchester Patriotic Union formed by radicals from the Manchester Observer. Johnson, the union's secretary, wrote to Henry Hunt asking him to chair a meeting in Manchester on 2 August 1819. Johnson wrote:

Nothing but ruin and starvation stare one in the face [in the streets of Manchester and the surrounding towns], the state of this district is truly dreadful, and I believe nothing but the greatest exertions can prevent an insurrection. Oh, that you in London were prepared for it.[21]

Unknown to Johnson and Hunt, the letter was intercepted by government spies and copied before being sent to its destination, confirming the government's belief that an armed rising was planned.

The mass public meeting planned for 2 August was delayed until 9 August. The Manchester Observer reported it was called "to take into consideration the most speedy and effectual mode of obtaining Radical reform in the Common House of Parliament" and "to consider the propriety of the 'Unrepresented Inhabitants of Manchester' electing a person to represent them in Parliament". The government's legal advice was that to elect a representative without a royal writ for an election was a criminal offence, and the magistrates decided to declare the meeting illegal.[22]

On 3 August however the Home Office conveyed to the magistrates the view of the Attorney-General that it was not the intention to elect an MP that was illegal, but the execution of that intention. It advised against any attempt to forcibly prevent the 9 August meeting unless there was an actual riot:

even if they should utter sedition or proceed to the election of a representative Lord Sidmouth is of opinion that it will be the wisest course to abstain from any endeavour to disperse the mob, unless they should proceed to acts of felony or riot. We have the strongest reason to believe that Hunt means to preside and to deprecate disorder.[23]

The radicals' own legal advice however urged caution, and so the meeting was accordingly cancelled and rearranged for 16 August, with its declared aim solely "to consider the propriety of adopting the most LEGAL and EFFECTUAL means of obtaining a reform in the Common House of Parliament".[19]

Samuel Bamford, a local radical who led the Middleton contingent, wrote that "It was deemed expedient that this meeting should be as morally effective as possible, and, that it should exhibit a spectacle such as had never before been witnessed in England."[24] Instructions were given to the various committees forming the contingents that "Cleanliness, Sobriety, Order and Peace" and a "prohibition of all weapons of offence or defence" were to be observed throughout the demonstration.[25] Each contingent was drilled and rehearsed in the fields of the towns around Manchester adding to the concerns of the authorities.[26] A royal proclamation forbidding the practice of drilling had been posted in Manchester on 3 August[27] but on 9 August an informant reported to Rochdale magistrates that at Tandle Hill the previous day, 700 men were "drilling in companies" and "going through the usual evolutions of a regiment" and an onlooker had said the men "were fit to contend with any regular troops, only they wanted [i.e. lacked] arms". The magistrates were convinced that the situation was indeed an emergency which would justify pre-emptive action, as the Home Office had previously explained, and set about lining up dozens of local loyalist gentlemen to swear the necessary oaths that they believed the town to be in danger.[22]

Assembly

[edit]| Contingents sent to St Peter's Field[28] Use a cursor to explore this imagemap. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Altrincham | Middleton | 3,000[29] | ||

| Ashton-under-Lyne | 2,000[29] | Mossley | ||

| Atherton | Oldham | 6,000–10,000[29][30] | ||

| Bolton | Rochdale | 3,000[29] | ||

| Bury | 3,000[29] | Royton | ||

| Chadderton | Saddleworth | |||

| Crompton | Salford | |||

| Eccles | Stalybridge | |||

| Failsworth | Stretford | |||

| Gee Cross | Stockport | 1,500–5,000[29][31] | ||

| Heywood | Urmston | |||

| Irlam | Westhoughton | |||

| Lees | Whitefield | |||

| Leigh | Wigan | |||

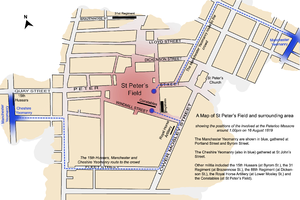

Preparations

[edit]St Peter's Field was a piece of land alongside Mount Street which was being cleared to enable the last section of Peter Street to be constructed. Piles of timber lay at the end of the field nearest to the Friends Meeting House, but the remainder of the field was clear.[32] Thomas Worrell, Manchester's Assistant Surveyor of Paving, arrived to inspect the field at 7:00 am. His job was to remove anything that might be used as a weapon, and he duly had "about a quarter of a load" of stones carted away.[33]

Monday, 16 August 1819,[1] was a hot summer's day, with a cloudless blue sky. The fine weather almost certainly increased the size of the crowd significantly; marching from the outer townships in the cold and rain would have been a much less attractive prospect.[34]

The Manchester magistrates met at 9:00 am, to breakfast at the Star Inn on Deansgate and to consider what action they should take on Henry Hunt's arrival at the meeting. By 10:30 am they had come to no conclusions, and moved to a house on the south-eastern corner of St Peter's Field, from where they planned to observe the meeting.[35] They were concerned that it would end in a riot, or even a rebellion, and had arranged for a substantial number of regular troops and militia yeomanry to be deployed. The military presence comprised 600 men of the 15th Hussars; several hundred infantrymen; a Royal Horse Artillery unit with two six-pounder guns; 400 men of the Cheshire Yeomanry; 400 special constables; and 120 cavalry of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry. The Manchester & Salford Yeomanry were relatively inexperienced militia recruited from among local shopkeepers and tradesmen, the most numerous of which were publicans. [36] Recently mocked by the Manchester Observer as "generally speaking, the fawning dependents of the great, with a few fools and a greater proportion of coxcombs, who imagine they acquire considerable importance by wearing regimentals,"[37] they were subsequently variously described as "younger members of the Tory party in arms",[8] and as "hot-headed young men, who had volunteered into that service from their intense hatred of Radicalism."[38] Socialist writer Mark Krantz has described them as "the local business mafia on horseback".[39] R J White described them as "exclusively cheesemongers, ironmongers and newly enriched manufacturers, (who) the people of Manchester … thought … a joke."[40]

The British Army in the north was under the overall command of General Sir John Byng. When he had initially learned that the meeting was scheduled for 2 August he wrote to the Home Office stating that he hoped the Manchester magistrates would show firmness on the day:

I will be prepared to go there, and will have in that neighbourhood, that is within an easy day's march, 8 squadron of cavalry, 18 companies of infantry and the guns. I am sure I can add to the Yeomanry if requisite. I hope therefore the civil authorities will not be deterred from doing their duty.[41]

He then excused himself from attendance, however, as the meeting on the 9th clashed with the horse races at York, a fashionable event at which Byng had entries in two races. He wrote to the Home Office, saying that although he would still be prepared to be in command in Manchester on the day of the meeting if it was thought really necessary, he had absolute confidence in his deputy commander, Lieutenant Colonel Guy L'Estrange.[42] The postponement to 16 August made it possible for Byng to attend after the races but he chose not to, having had enough of dealing with the Manchester magistrates. He had dealt firmly and bloodlessly with the Blanketeers two years before; L'Estrange was to exhibit no such qualities of command.[43]

Meeting

[edit]The crowd that gathered in St Peter's Field arrived in disciplined and organised contingents. Contingents were sent from all around the region, the largest and "best dressed" of which was a group of 10,000 who had travelled from Oldham Green, comprising people from Oldham, Royton (which included a sizeable female section), Crompton, Lees, Saddleworth and Mossley.[30] Other sizeable contingents marched from Middleton and Rochdale (6,000 strong) and Stockport (1,500–5,000 strong).[31] Reports of the size of the crowd at the meeting vary substantially. Contemporaries estimated it from 30,000 to as many as 150,000; modern estimates have been 50,000–80,000.[44] Recent work however has reduced these numbers. A reasonably reliable count of the numbers on the various marches indicates a total of around 20,000 who came in from outside Manchester, but the number who attended informally from Manchester and Salford is much harder to estimate. Bush argues from the casualty figures that two-thirds were from Manchester and Salford, suggesting a total crowd of 50,000,[45] but Poole revises this to a half, bringing the total down to 40,000.[46] Steele's estimate of the capacity of the ground suggests 30,000 which, if correct, lowers the attendance but raises the casualty rate.[47]

The assembly was intended by its organisers to be a peaceful meeting; Henry Hunt had exhorted everyone attending to come "armed with no other weapon but that of a self-approving conscience",[48] and many were wearing their "Sunday best" clothes.[32] Samuel Bamford recounts the following incident, which occurred as the Middleton contingent reached the outskirts of Manchester:

On the bank of an open field on our left I perceived a gentleman observing us attentively. He beckoned me, and I went to him. He was one of my late employers. He took my hand, and rather concernedly, but kindly, said he hoped no harm was intended by all those people who were coming in. I said "I would pledge my life for their entire peaceableness." I asked him to notice them, "did they look like persons wishing to outrage the law? were they not, on the contrary, evidently heads of decent working families? or members of such families?" "No, no," I said, "my dear sir, and old respected master, if any wrong or violence take place, they will be committed by men of a different stamp from these." He said he was very glad to hear me say so; he was happy he had seen me, and gratified by the manner in which I had expressed myself. I asked, did he think we should be interrupted at the meeting? he said he did not believe we should; "then," I replied, "all will be well"; and shaking hands, with mutual good wishes, I left him, and took my station as before.[49]

Although William Robert Hay, chairman of the Salford Hundred Quarter Sessions, claimed that "The active part of the meeting may be said to have come in wholly from the country",[50] others such as John Shuttleworth, a local cotton dealer, estimated that most were from Manchester, a view that would subsequently be supported by the casualty lists. Of the casualties whose residence was recorded, sixty-one per cent lived within a three-mile radius of the centre of Manchester.[51] Some groups carried banners with texts like "No Corn Laws", "Annual Parliaments", "Universal suffrage" and "Vote By Ballot".[52] The first female reform societies were established in the textile areas in 1819 and women from the Manchester Female Reform Society, dressed in white, accompanied Hunt to the platform. The society's president Mary Fildes rode in Hunt's carriage carrying its flag.[53] The only banner known to have survived is in Middleton Public Library; it was carried by Thomas Redford, who was injured by a yeomanry sabre. Made of green silk embossed with gold lettering, one side of the banner is inscribed "Liberty and Fraternity" and the other "Unity and Strength."[52] It is the world's oldest political banner.[54]

At about noon, several hundred special constables were led onto the field. They formed two lines in the crowd a few yards apart, in an attempt to form a corridor through the crowd between the house where the magistrates were watching and the hustings, two wagons lashed together. Believing that this might be intended as the route by which the magistrates would later send their representatives to arrest the speakers, some members of the crowd pushed the wagons away from the constables, and pressed around the hustings to form a human barrier.[55]

Hunt's carriage arrived at the meeting shortly after 1:00 pm, and he made his way to the hustings. Alongside Hunt on the speakers' stand were John Knight, a cotton manufacturer and reformer, Joseph Johnson, the organiser of the meeting, John Thacker Saxton, managing editor of the Manchester Observer, the publisher Richard Carlile, and George Swift, reformer and shoemaker. There were also a number of reporters, including John Tyas of The Times, John Smith of the Liverpool Mercury and Edward Baines Jr, the son of the editor of the Leeds Mercury.[56] By this time St Peter's Field, an area of 14,000 sq yd (11,700 m2), was packed with tens of thousands of men, women and children. The crowd around the speakers was so dense that "their hats seemed to touch"; large groups of curious spectators gathered on the outskirts of the crowd.

Cavalry charge

[edit]When I wrote these two letters, I considered at that moment that the lives and properties of all the persons in Manchester were in the greatest possible danger. I took this into consideration, that the meeting was part of a great scheme, carrying on throughout the country.[57]

William Hulton, the chairman of the magistrates watching from the house on the edge of St Peter's Field, saw the enthusiastic reception that Hunt received on his arrival at the assembly, and it encouraged him to action. He issued an arrest warrant for Henry Hunt, Joseph Johnson, John Knight, and James Moorhouse. On being handed the warrant the Constable, Jonathan Andrews, offered his opinion that the press of the crowd surrounding the hustings would make military assistance necessary for its execution. Hulton then wrote two letters, one to Major Thomas Trafford, the commanding officer of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry, and the other to the overall military commander in Manchester, Lieutenant Colonel Guy L'Estrange. The contents of both notes were similar:[58]

Sir, as chairman of the select committee of magistrates, I request you to proceed immediately to no. 6 Mount Street, where the magistrates are assembled. They consider the Civil Power wholly inadequate to preserve the peace. I have the honour, & c. Wm. Hulton.[57]

— Letter sent by William Hulton to Major Trafford of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry

The notes were handed to two horsemen who were standing by. The Manchester and Salford Yeomanry were stationed just a short distance away in Portland Street, and so received their note first. They immediately drew their swords and galloped towards St Peter's Field. One trooper, in a frantic attempt to catch up, knocked down Ann Fildes in Cooper Street, causing the death of her son when he was thrown from her arms;[59] two-year-old William Fildes was the first casualty of Peterloo.[60]

Sixty cavalrymen of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, led by Captain Hugh Hornby Birley, a local factory owner, arrived at the house from where the magistrates were watching; some reports allege that they were drunk.[61] Andrews, the Chief Constable, instructed Birley that he had an arrest warrant which he needed assistance to execute. Birley was asked to take his cavalry to the hustings to allow the speakers to be removed; it was by then about 1:40 pm.[62]

The route towards the hustings between the special constables was narrow, and as the inexperienced horses were thrust further and further into the crowd they reared and plunged as people tried to get out of their way.[59] The arrest warrant had been given to the Deputy Constable, Joseph Nadin, who followed behind the yeomanry. As the cavalry pushed towards the speakers' stand they became stuck in the crowd, and in panic started to hack about them with their sabres.[63] On his arrival at the stand Nadin arrested Hunt, Johnson and a number of others including John Tyas, the reporter from The Times.[64] Their mission to execute the arrest warrant having been achieved, the yeomanry set about destroying the banners and flags on the stand.[65][66] According to Tyas, the yeomanry then attempted to reach flags in the crowd "cutting most indiscriminately to the right and to the left to get at them" – only then (said Tyas) were brickbats thrown at the military: "From this point the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry lost all command of temper".[65] From his vantage point William Hulton perceived the unfolding events as an assault on the yeomanry, and on L'Estrange's arrival at 1:50 pm, at the head of his hussars, he ordered them into the field to disperse the crowd with the words: "Good God, Sir, don't you see they are attacking the Yeomanry; disperse the meeting!"[67] The 15th Hussars formed themselves into a line stretching across the eastern end of St Peter's Field, and charged into the crowd. At about the same time the Cheshire Yeomanry charged from the southern edge of the field.[68] At first the crowd had some difficulty in dispersing, as the main exit route into Peter Street was blocked by the 88th Regiment of Foot, standing with bayonets fixed. One officer of the 15th Hussars was heard trying to restrain the by now out of control Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, who were "cutting at every one they could reach": "For shame! For shame! Gentlemen: forbear, forbear! The people cannot get away!"[69]

On the other hand, Lieutenant Jolliffe of the 15th Hussars said "It was then for the first time that I saw the Manchester troop of Yeomanry; they were scattered singly or in small groups over the greater part of the Field, literally hemmed up and powerless either to make an impression or to escape; in fact, they were in the power of those whom they were designed to overawe and it required only a glance to discover their helpless position, and the necessity of our being brought to their rescue" [70] Further Jolliffe asserted that "… nine out of ten of the sabre wounds were caused by the Hussars … however, the far greater amount of injuries were from the pressure of the routed multitude." [70]

Within ten minutes the crowd had been dispersed, at the cost of 11 dead and more than 600 injured. Only the wounded, their helpers, and the dead were left behind; a woman living nearby said she saw "a very great deal of blood."[26] For some time afterwards there was rioting in the streets, most seriously at New Cross, where troops fired on a crowd attacking a shop belonging to someone rumoured to have taken one of the women reformers' flags as a souvenir. Peace was not restored in Manchester until the next morning, and in Stockport and Macclesfield rioting continued on the 17th.[71] There was also a major riot in Oldham that day, during which one person was shot and wounded.[26]

Victims

[edit]

The exact number of those killed and injured at Peterloo has never been established with certainty, for there was no official count or inquiry and many injured people fled to safety without reporting their injuries or seeking treatment. The Manchester Relief Committee, a body set up to provide relief for the victims of Peterloo, gave the number of injured as 420, while Radical sources listed 500.[72] The true number is difficult to estimate, as many of the wounded hid their injuries for fear of retribution by the authorities. Three of William Marsh's six children worked in the factory belonging to Captain Hugh Birley of the Manchester Yeomanry, and lost their jobs because their father had attended the meeting.[73] James Lees was admitted to Manchester Infirmary with two severe sabre wounds to the head, but was refused treatment and sent home after refusing to agree with the surgeon's insistence that "he had had enough of Manchester meetings."[73]

A particular feature of the meeting at Peterloo was the number of women present. Female reform societies had been formed in North West England during June and July 1819, the first in Britain. Many of the women were dressed distinctively in white, and some formed all-female contingents, carrying their own flags.[74] Of the 654 recorded casualties, at least 168 were women, four of whom died either at St Peter's Field or later as a result of their wounds. It has been estimated that less than 12 per cent of the crowd was made up of women, suggesting that they were at significantly greater risk of injury than men by a factor of almost 3:1. Richard Carlile claimed that the women were especially targeted, a view apparently supported by the large number who suffered from wounds caused by weapons.[45] A recently unearthed set of 70 victims' petitions in the parliamentary archives reveals some shocking tales of ferocity, including the accounts of the female reformers Mary Fildes, who carried the flag on the platform, and Elizabeth Gaunt, who suffered a miscarriage following ill-treatment during eleven days' detention without trial.[75]

Eleven of the fatalities listed occurred on St Peter's Field. Others, such as John Lees of Oldham, died later of their wounds, and some like Joshua Whitworth were killed in the rioting that followed the crowd's dispersal from the field.[72] Bush puts the fatalities at 18 and Poole supports this figure, albeit a slightly different 18 based on new information. It is these 18 whose names are carved on the 2019 memorial, including the unborn child of Elizabeth Gaunt.[76]

| Name | Abode | Date of death | Cause | Notes | Ref(s). |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| John Ashton | Cowhill, Chadderton | 16 August | Sabred and trampled on by crowd | Carried the black flag of the Saddleworth, Lees and Mossley Union, inscribed "Taxation without representation is unjust and tyrannical. NO CORN LAWS". The inquest jury returned a verdict of accidental death. His son, Samuel, received 20 shillings in relief. | |

| John Ashworth | Bulls Head, Manchester | Sabred and trampled | Ashworth was a Special Constable, accidentally killed by the cavalry. | ||

| William Bradshaw | Lily-hill, Bury | Shot by musket | |||

| Thomas Buckley | Baretrees, Chadderton | Sabred and stabbed by bayonet | |||

| Robert Campbell | Miller Street, Salford | 18 August | Killed by a mob in Newton Lane | Campbell was a Special Constable, beaten to death in a revenge attack the next day and not a victim on the field. His name is not on the memorial. | |

| James Crompton | Barton-upon-Irwell | Trampled on by the cavalry | Buried 1 September | ||

| Edmund Dawson[a] | Saddleworth | Died of sabre wounds at the Manchester Infirmary. | |||

| Margaret Downes | Manchester | Sabred | |||

| William Evans | Hulme | Trampled by cavalry | Evans was a Special Constable. | ||

| William Fildes | Kennedy Street, Manchester | 16 August | Ridden over by cavalry | Two years old, he was first victim of the massacre. His mother was carrying him across the road when she was struck by a trooper of the Manchester Yeomanry, galloping towards St Peters Field. | |

| Mary Heys | Oxford Road, Manchester | 17 December | Ridden over by cavalry | Mother of six children, and pregnant at the time of the meeting. Disabled and suffering from almost daily fits following her injuries, the premature birth of her child after 7 months of pregnancy resulted in her death. | |

| Sarah Jones | 96 Silk Street, Salford | No cause given by Marlow but listed by Frow as "bruised in the head". | Mother of seven children. Beaten on the head by a Special Constable's truncheon. | ||

| John Lees | Oldham | 9 September | Sabred | Lees was an ex-soldier who had fought in the Battle of Waterloo. | |

| Arthur Neil | Pidgeon Street, Manchester | January 1820 | Inwardly crushed | Arthur Neil (or O'Neill) died after being imprisoned without trial for five months. | |

| Martha Partington | Eccles | Thrown into a cellar and killed on the spot | |||

| John Rhodes | Pits, Hopwood | 18 or 19 November | Sabre wound to the head | Rhodes's body was dissected by order of magistrates who wished to prove that his death was not a result of Peterloo. The coroner's inquest found that he had died from natural causes. | |

| Joshua Whitworth | 16 August | Shot at New Cross the same evening by infantry firing on rioters. |

Reaction and aftermath

[edit]Public

[edit]PETER LOO MASSACRE ! ! ! Just published No. 1 price twopence of PETER LOO MASSACRE Containing a full, true and faithful account of the inhuman murders, woundings and other monstrous Cruelties exercised by a set of INFERNALS (miscalled Soldiers) upon unarmed and distressed People.[78]

|

||

| — 28 August 1819, Manchester Observer | ||

| As the 'Peterloo Massacre' cannot be otherwise than grossly libellous you will probably deem it right to proceed by arresting the publishers.[78] | ||

| — 25 August 1819, Letter from the Home Office to Magistrate James Norris | ||

The Peterloo Massacre has been called one of the defining moments of its age.[79] Many of those present at the massacre, including local masters, employers and owners, were horrified by the carnage. One of the casualties, Oldham cloth-worker and ex-soldier John Lees, who died from his wounds on 9 September, had been present at the Battle of Waterloo.[26] Shortly before his death he said to a friend that he had never been in such danger as at Peterloo: "At Waterloo there was man to man but there it was downright murder."[80] When news of the massacre began to spread, the population of Manchester and surrounding districts was horrified and outraged.[81]

After the events at Peterloo, many commemorative items such as plates, jugs, handkerchiefs and medals were produced; they were carried by radical supporters and may also have been sold to raise money for the injured.[82] The People's History Museum in Manchester has one of these Peterloo handkerchiefs on display.[83] All the mementos carried the iconic image of Peterloo; cavalrymen with swords drawn riding down and slashing at defenceless civilians.[84] The reverse of the Peterloo commemorative medal carried a Biblical text, derived from Psalm 37 (Psalm 37:14):

The wicked have drawn out the sword, they have cast down the poor and needy and such as be of upright conversation.[85]

Peterloo was the first public meeting at which journalists from important, distant newspapers were present and within a day or so of the event, accounts were published in London, Leeds and Liverpool.[59] The London and national papers shared the horror felt in the Manchester region, and the feeling of indignation throughout the country became intense. James Wroe, editor of the Manchester Observer, was the first to describe the incident as the "Peterloo Massacre", coining his headline by creating the ironic portmanteau from St Peter's Field and the Battle of Waterloo that had taken place four years earlier.[86] He also wrote pamphlets entitled "The Peterloo Massacre: A Faithful Narrative of the Events". Priced at 2d each, they sold out every print run for 14 weeks and had a large national circulation.[86] Sir Francis Burdett, a reformist MP, was jailed for three months for publishing a seditious libel.[87]

Percy Bysshe Shelley was in Italy and did not hear of the massacre until 5 September. His poem The Masque of Anarchy, subtitled Written on the Occasion of the Massacre at Manchester, was sent for publication in the radical periodical The Examiner, but because of restrictions on the radical press it was not published until 1832, ten years after the poet's death.[88][89]

Political

[edit]The immediate effect of Peterloo was a crackdown on reform. The government instructed the police and courts to go after the journalists, presses and publication of the Manchester Observer.[86] Wroe was arrested and charged with producing a seditious publication. Found guilty he was sentenced to 12 months in prison and fined £100.[86] Outstanding court cases against the Manchester Observer were rushed through the courts and a continual change of sub-editors was not sufficient defence against a series of police raids, often on the suspicion that someone was writing a radical article. The Manchester Observer closed in February 1820.[86][90]

Hunt and eight others were tried at York Assizes on 16 March 1820, charged with sedition. After a two-week trial, five defendants were found guilty, on a single one of the seven charges. Hunt was sentenced to 30 months in Ilchester Gaol; Bamford, Johnson, and Healey were given one year each, and Knight was jailed for two years on a subsequent charge. A civil case on behalf of a weaver wounded at Peterloo was brought against four members of the Manchester Yeomanry, Captain Birley, Captain Withington, Trumpeter Meagher, and Private Oliver, at Lancaster Assizes, on 4 April 1822. All were acquitted, as the court ruled their actions had been justified to disperse an illegal gathering and that the murders were nothing more than self-defence.[91]

The government declared its support for the actions taken by the magistrates and the army. The Manchester magistrates held a supposedly public meeting on 19 August, so that resolutions supporting the action they had taken three days before could be published. Cotton merchants Archibald Prentice (later editor of The Manchester Times) and Absalom Watkin (a later corn-law reformer), both members of the Little Circle, organised a petition of protest against the violence at St Peter's Field and the validity of the magistrates' meeting. Within a few days it had collected 4,800 signatures.[92] Nevertheless, the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, on 27 August conveyed to the magistrates the thanks of the Prince Regent for their action in the "preservation of the public peace."[11] That public exoneration was met with fierce anger and criticism. During a debate at Hopkins Street Robert Wedderburn declared "The Prince is a fool with his Wonderful letters of thanks … What is the Prince Regent or King to us, we want no King – he is no use to us."[93] In an open letter, Richard Carlile said:

Unless the Prince calls his ministers to account and relieved his people, he would surely be deposed and make them all REPUBLICANS, despite all adherence to ancient and established institutions.[93]

For a few months following Peterloo it seemed to the authorities that the country was heading towards an armed rebellion. Encouraging them in that belief were two abortive uprisings, in Huddersfield and Burnley, the Yorkshire West Riding Revolt, during the autumn of 1820, and the discovery and foiling of the Cato Street conspiracy to blow up the cabinet that winter.[94] By the end of the year, the government had introduced legislation, later known as the Six Acts, to suppress radical meetings and publications, and by the end of 1820 every significant working-class radical reformer was in jail; civil liberties had declined to an even lower level than they were before Peterloo. Historian Robert Reid has written that "it is not fanciful to compare the restricted freedoms of the British worker in the post-Peterloo period in the early nineteenth century with those of the black South African in the post-Sharpeville period of the late twentieth century."[95] Peterloo is also partially credited for pushing the British government to pass the Vagrancy Act, and for the creation of the London Metropolitan Police (sometimes described as the first police department).[96]

The Peterloo Massacre also influenced the naming of the 1821 Cinderloo Uprising in the Coalbrookdale Coalfield of east Shropshire. The uprising saw 3,000 protesting workers confronted by the South Shropshire Yeomanry,[97] leading to the deaths of 3 crowd members.[98][99]

One direct consequence of Peterloo was the foundation of The Manchester Guardian newspaper in 1821, by the Little Circle group of non-conformist Manchester businessmen headed by John Edward Taylor, a witness to the massacre.[8] The prospectus announcing the new publication proclaimed that it would "zealously enforce the principles of civil and religious Liberty … warmly advocate the cause of Reform … endeavour to assist in the diffusion of just principles of Political Economy and … support, without reference to the party from which they emanate, all serviceable measures."[100]

Events such as the Pentrich rising, the March of the Blanketeers and the Spa Fields meeting, all serve to indicate the breadth, diversity and widespread geographical scale of the demand for economic and political reform at the time.[101] Peterloo had no effect on the speed of reform, but in due course all but one of the reformers' demands, annual parliaments, were met.[102] Following the Great Reform Act of 1832, the newly created Manchester parliamentary borough elected its first two MPs. Five candidates including William Cobbett stood, and the Whigs, Charles Poulett Thomson and Mark Philips, were elected.[103] Manchester became a Municipal Borough in 1838, and the manorial rights were purchased by the borough council in 1846.[104]

On the other hand, R. J. White has affirmed the true significance of Peterloo as marking the point of final conversion of provincial England to the struggle for enfranchisement of the working class. "The ship which had tacked and lain for so long among the shoals and shallows of Luddism, hunger-marching, strikes and sabotage, was coming to port"; "Henceforth, the people were to stand with ever greater fortitude behind that great movement, which, stage by stage throughout the nineteenth century, was to impose a new political order upon society"; "With Peterloo, and the departure of Regency England, parliamentary reform had come of age."[105]

Commemorations

[edit]The Skelmanthorpe Flag, believed to have been made in Skelmanthorpe, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, in 1819, was made to honour the victims of the Peterloo Massacre and was flown at mass meetings held in the area demanding the reform of Parliament.[106] This was one of dozens of mass protest meetings held in 1819, until the Six Acts put an end to protests.[107] Throughout the nineteenth century, the memory of Peterloo was a political rallying point for both radicals and liberals to attack the Tories and demand further reforms of parliament. These came at the rate of one per generation in 1832, 1867, 1884, and 1918, when universal manhood suffrage and partial female suffrage was achieved.[108][109]

The Free Trade Hall, home of the Anti-Corn Law League, was built partly as a "cenotaph raised on the shades of the victims" of Peterloo, but one which acknowledged only the reformers' demand for the repeal of the corn laws and not for the vote.[110] At the centenary in 1919, just two years after the Russian Revolution and the Bolshevik coup, trade unionists and communists alike saw Peterloo as a lesson that workers needed to fight back against capitalist violence. The Conservative majority on Manchester City Council in 1968–1969 declined to mark the 150th anniversary of Peterloo, but their Labour successors in 1972 placed a blue plaque high up on the wall of the Free Trade Hall, now the Radisson Hotel. This in turn was criticised for failing to recognise that anyone was killed or injured.[8] In a 2006 survey conducted by The Guardian, Peterloo came second to St. Mary's Church, Putney, the venue for the Putney Debates, as the event from radical British history that most deserved a proper monument.[111] The euphemism on the blue plaque was described by comedian and activist Mark Thomas as "an act of historical vandalism akin to Stalin airbrushing dissidents out of photographs".[112][113] A Peterloo Memorial Campaign was set up to lobby for a 'Respectful, Informative and Permanent' (RIP) monument to an event that has been described as "Manchester's Tiananmen Square".[114][115]

In 2007, Manchester City Council replaced the original blue plaque with a red one, giving a fuller account of the events of 1819. It was unveiled on 10 December 2007 by the Lord Mayor of Manchester, Councillor Glynn Evans.[116] Under the heading "St. Peter's Fields: The Peterloo Massacre", the present plaque reads, "On 16th August 1819 a peaceful rally of 60,000 pro-democracy reformers, men, women and children, was attacked by armed cavalry resulting in 15 deaths and over 600 injuries."[112][113]

Memorial

[edit]

In 2019, shortly before the 200th anniversary of the massacre, Manchester City Council "quietly unveiled" a new memorial by the artist Jeremy Deller.[117] It was inaugurated at a large public gathering on 16 August 2019, widely reported in the press, covered extensively on regional TV and radio, and marked by a special edition of the Manchester Evening News.[118]

The 1.5-metre-high memorial features 11 concentric steps engraved, sculpted from polished local stone and carved with the names of the dead and the places from which the victims came. The material not visible from the ground is reproduced at ground level, and there is a floor plaque.[119]

While this met the official standards for access, it was also interpreted by some as a 'speaking platform' made inaccessible by its stepped design. The city council has promised that it will be modified to rectify this. Some disability campaigners described the memorial as 'vile' and calling for it to be demolished, a stance which in turn caused offence by appearing to dismiss the experiences of the many disabled victims of Peterloo. It has in practice proved very difficult to design a wheelchair ramp that does not damage or block substantial parts of the inscriptions.[117][119]

The memorial has meanwhile become widely appreciated and visited, and the Peterloo Memorial Campaign site states that it is 'Proud to have campaigned for a respectful, informative and permanent Peterloo Memorial at the heart of Manchester'.[120][121]

Representations in popular culture

[edit]In 1968, in celebration of the centenary of its first meeting, the Trades Union Congress commissioned British composer Sir Malcolm Arnold to write the Peterloo Overture. The organist Jonathan Scott recorded a solo work, 'Peterloo 1819', at the parish church in the radical village of Royton in 2017. Scott is a descendant of the wider family of the Peterloo radical Samuel Bamford from nearby Middleton.[122] Several musical pieces in different genres from rap to oratorio were commissioned and performed in connection with the 2019 Peterloo bicentenary.[123] Other musical commemorations include Harvey Kershaw MBE's folk revival song, which was recorded by the Oldham Tinkers (listen), "Ned Ludd Part 5" on British folk rock group Steeleye Span's 2006 album Bloody Men, and Rochdale rock band Tractor's suite of five songs written and recorded in 1973, later included on their 1992 release Worst Enemies.[124] The long history of verse about Peterloo is covered in Alison Morgan's 2018 book Ballads and Songs of Peterloo.[125] In 2019 a whole volume of essays was devoted to the commemoration of Peterloo, including an essay by Ian Haywood on 'The Sounds of Peterloo' and other contributions covering Hunt, Cobbett, Castlereagh, Bentham, Wordsworth, Shelley, Scotland, and Ireland.[126]

The 2018 Mike Leigh film Peterloo is based on the events at Peterloo.[127] The 1947 film Fame Is the Spur, based on the Howard Spring novel of the same name, depicts the rise of a politician inspired by his grandfather's account of the massacre.[128] Recent novels about Peterloo include Carolyn O'Brien's The Song of Peterloo[129] and Jeff Kaye's All the People.[130] The most important fictional treatment remains Isabella Banks's 1876 novel, The Manchester Man, for its author lived in Manchester at the time and wove into her account numerous testimonies she picked up from people who were involved.[131] It was also the subject of a graphic novel in 'verbatim' form, Peterloo: Witnesses to a Massacre, with the story told mainly through words written and spoken at the time.[18] In 2016, Big Finish released a Doctor Who audio adventure based around the events of the Peterloo Massacre.

Sean Cooney, songwriter, folk singer and member of The Young'uns, wrote a work consisting of 15 original songs and a spoken narrative commemorating the Peterloo Massacre. The work received its premiere at FolkEast on 16 August 2024, the 205th anniversary of Peterloo, with Eliza Carthy and Sam Carter joining Sean Cooney on the Moot Hall stage.[132]

See also

[edit]- History of Manchester

- Bristol riot of Queen's Square, 1831

- Cinderloo Uprising, 1821

- List of massacres in Great Britain

Notes

[edit]- ^ A William Dawson of Saddleworth is also sometimes mentioned, but Poole (2019) has established that this was an error in the original source.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "History GCSE / National 5: What was the Peterloo Massacre of 1819?". BBC Teach. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Poole (2019), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Poole, Robert (2019). "The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper, part 7: 'Enter the Guardian'". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 95, 1: 96–102. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020 – via Open access at publisher's site.

- ^ Poole (2019), pp. 80–84.

- ^ a b Reid (1989), p. 28

- ^ a b "The Great Reform Act". BBC News Online. 19 May 1998. Archived from the original on 4 March 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ^ data re-presented in Document 168 Table of Parliamentary Patronage 1794–1816 in Aspinall, A.; Smith, Anthony, eds. (1995). English Historical Documents, 1783–1832 (reprint ed.). Psychology Press. pp. 223–236. ISBN 978-0-415-14373-8. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Wainwright, Martin (13 August 2007). "Battle for the memory of Peterloo: Campaigners demand fitting tribute". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ^ a b Frangopulo (1977), p. 30

- ^ a b Hernon (2006), p. 22

- ^ a b Farrer, William; Brownbill, John (2003–2006) [1911]. "The city and parish of Manchester: Introduction". The Victoria history of the county of Lancaster. – Lancashire. Vol. 4. University of London & History of Parliament Trust. Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- ^ Glen (1984), pp. 194–252

- ^ "Petition of the Manchester Reformers". Chester Courant. 25 March 1817.

- ^ Poole, Robert (2019). "Petitioners and Rebels: Petitioning for Parliamentary Reform in Regency England". Social Science History. 43, 3 (3): 553–580. doi:10.1017/ssh.2019.22 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Chester Spring Assizes – Trial of Johnston, Drummond and Bagguley, for Sedition and Conspiracy". Chester Courant. 20 April 1819.

- ^ "Provincial Intelligence". The Examiner. 25 January 1819.

- ^ Poole (2019), ch. 6 & pp. 175–177.

- ^ a b Polyp, Sclunke & Poole (2019). Peterloo: witnesses to a massacre. Oxford: New Internationalist. pp. 17–21. ISBN 978-1-78026-475-2. OCLC 1046071859. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b Taylor, John Edward (1820). Notes and observations, critical and explanatory, on the papers relative to the internal state of the country. E Wilson. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Poole (2019), ch. 10.

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 115

- ^ a b Poole (2019), Ch. 11.

- ^ Hobhouse, H. "A letter sent to Manchester on behalf of Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary, 4 August 1819 (Catalogue ref: HO 41/4 f.434)". National Archives: Education: Power, Politics and Protest: The growth of political rights in Britain in the 19th century. National Archives. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ Bamford (1844), Ch. 30.

- ^ Frangopulo (1977), p. 31

- ^ a b c d McPhillips (1977), pp. 22–23

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 125

- ^ Poole (2019), p. 431 note 57.

- ^ a b c d e f Bush (2005), p. 11

- ^ a b Marlow (1969), p. 118

- ^ a b Marlow (1969), pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b Frow & Frow (1984), p. 7

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 145

- ^ Marlow (1969), p. 119

- ^ Reid (1989), pp. 152–153

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 88

- ^ Bruton (1919), p. 14

- ^ Prentice (1853), p. 160

- ^ Krantz (2011), p. 12

- ^ White (1957), p. 185

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 136

- ^ Riding, Jacqueline (2018). Peterloo: the story of the Manchester massacre. London: Head of Zeus. pp. 157–165, 203–205. ISBN 978-1-78669-583-3. OCLC 1017592330.

- ^ Poole (2019).

- ^ Marlow (1969), p. 125

- ^ a b c Bush, M. L. (2005). The casualties of Peterloo. Lancaster: Carnegie Pub. ISBN 1-85936-125-0. OCLC 71224394.

- ^ Poole (2019), pp. 360–364.

- ^ Steele, David (8 August 1819). "A more shocking massacre? How we might have over-estimated the Peterloo crowds". BBC History Extra. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 148

- ^ Bamford (1844), p. 202

- ^ Frangopulo (1977), p. 33

- ^ Bush (2005), p. 19

- ^ a b Marlow (1969), pp. 119–120

- ^ Vallance (2013), p. 10

- ^ Poole, Robert (2014). "The Middleton Peterloo Banner". Return to Peterloo. Manchester: Carnegie. pp. 159–171. ISBN 978-1-85936-225-9. OCLC 893558457.

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 161

- ^ Reid (1989), pp. 162–163

- ^ a b Reid (1989), p. 167

- ^ Reid (1989), pp. 166–167

- ^ a b c Frow & Frow (1984), p. 8

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 168

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 156

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 170

- ^ Poole, Robert (2006), "'By the Law or the Sword': Peterloo Revisited", History, 91 (302): 254–276, doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.2006.00366.x

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 185

- ^ a b Read (1819), p. 5

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 180

- ^ Walmsley (1969), p. 214

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 175

- ^ Poole (2019), Ch. 13.

- ^ a b Bruton (1921), p. 14

- ^ Reid (1989), pp. 186–187

- ^ a b Marlow (1969), pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b Bush (2005), p. 12

- ^ Bush (2005), p. 1

- ^ Poole (2019), ch. 13 & pp. 353–355, 374–377.

- ^ a b Poole 2019, pp. 345–352

- ^ "Fatalities spreadsheet". Peterloo Memorial Campaign. 2019. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b Marlow (1969), p. 6.

- ^ Poole (2006), p. 254

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 201

- ^ Donald, Diana (1989). "The Power of Print: Graphic Images of Peterloo" (PDF). Manchester Region History Review. 3: 21–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2008.

- ^ Burgess, Chris (2014). "The objects of Peterloo". In Poole, Robert (ed.). Return to Peterloo. Manchester: Carnegie. pp. 151–158. ISBN 978-1-85936-225-9. OCLC 893558457.

- ^ Collection highlights, Peterloo Handkerchief, People's History Museum, archived from the original on 13 January 2015, retrieved 13 January 2015

- ^ Bush (2005), pp. 30, 35

- ^ illustrated (facing p. 44) in Bruton 1919

- ^ a b c d e Harrison, Stanley (1974). Poor Men's Guardians: Survey of the Democratic and Working-class Press. Lawrence & W. ISBN 978-0-85315-308-5.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Holland, Arthur William (1911). "Burdett, Sir Francis". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 809–810.

- ^ Sandy, Mark (20 September 2002). "The Mask of Anarchy". The Literary Encyclopedia. The Literary Dictionary Company Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ^ Cox, Michael, ed. (2004). The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860634-6.

- ^ Poole, Robert (2019). "The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 95 (1): 31–123. doi:10.7227/BJRL.95.1.3.

- ^ Manchester Meeting, sixteenth of August, 1819. A Report of the Trial, Redford against Birley and others for an assault, etc. James Harrop. 1822. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 195

- ^ a b Poole (2000), p. 154

- ^ Poole (2006), p. 272

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 211

- ^ Vitale, Alex S. The end of policing. Verso Books, 2021.

- ^ Gladstone, E.W. (1953). The Shropshire Yeomanry 1795-1945, the Story of a Volunteer Cavalry Regiment. The Whitethorn Press. pp. 21–22.

- ^ Growcott, Mat (6 October 2018). "The riot that Telford forgot: New group trying to raise awareness of Cinderloo uprising". Shropshire Star. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ "Fatal Riot". Shrewsbury Chronicle. 9 February 1821.

- ^ "The Scott Trust: History". Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ Davis (1993), pp. 32–33

- ^ Reid (1989), p. 218

- ^ Prentice (1853), p. 25

- ^ Farrer, William; Brownbill, John, eds. (2017) [1911]. "Townships: Manchester (part 2 of 2)". The Victoria history of the county of Lancaster. – Lancashire. Vol. 4. University of London. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ White (1957), pp. 191–192

- ^ "The Skelmanthorpe Flag". BBC: A History of the World. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ Navickas, Katrina (2019). "The Multiple Geographies of Peterloo and its Impact in Britain". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 95, 1: 1–13. doi:10.7227/BJRL.95.1.1. hdl:2299/21505.

- ^ Wyke, Terry (2014). "Remembering the Manchester Massacre". In Poole, Robert (ed.). Return to Peterloo. Manchester: Carnegie. pp. 111–132. ISBN 978-1-85936-225-9. OCLC 893558457.

- ^ Joe Cozens, 'The Making of the Peterloo Martyrs', in (2018). K. Laybourn; Q. Outram (eds.). A History of Secular Martyrdom in the Britain and Ireland: From Peterloo to the Present. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-319-62905-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pickering & Tyrrell (2000), p. 204

- ^ Hunt, Tristram; Fraser, Giles (16 October 2006). "And the winner is ..." The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 July 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ^ a b Ward, David (27 December 2007). "New plaque tells truth of Peterloo killings 188 years on". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ^ a b "Blue Plaque". The Peterloo Memorial Campaign. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Hobson, Judy (17 August 2007). "Remember the Peterloo massacre?". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Paul (2014). "Remembering Peterloo in the 21st Century". In Poole, Robert (ed.). Return to Peterloo. Manchester: Carnegie. pp. 195–201. ISBN 978-1-85936-225-9. OCLC 893558457.

- ^ Manchester City Council (10 December 2007). "Peterloo memorial plaque unveiled". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ^ a b Halliday, Josh (13 August 2019). "Peterloo memorial quietly unveiled three days before anniversary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Peterloo 200 years on". Manchester Evening News. 16 August 2019. Archived from the original on 30 November 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b Halliday, Josh (16 August 2019). "Manchester gets ready for noisy tribute to the dead of Peterloo". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "@peterloomemoria". Peterloo Memorial Campaign Twitter feed. 2019. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Manchester City Council Communities and Equaklities Scrutiny Committee 5 March 2020 item 10". Manchester City Council video minutes. 5 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Scott, Jonathan (11 February 2017). "'Peterloo 2019' organ solo". YouTube. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Manchester Histories. "Projects: From the Crowd, Protest Music". Peterloo 1819 commemoration site. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Anon (1996). "tractor – Worst enemies". Discogs. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Morgan, Alison (2019). Ballads and songs of Peterloo. Manchester, England. ISBN 978-1-5261-4429-4. OCLC 1089015511.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Demson, Michael; Hewitt, Regina (2019). Commemorating Peterloo: violence, resilience and claim-making during the Romantic era. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-2858-3. OCLC 1124774617.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (4 April 2019). "'Peterloo' Review: Political Violence of the Past Mirrors the Present". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Anon (10 September 2012). "Fame Is the Spur". Time out. Time Out Group Plc. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ O'Brien, Carolyn. (2019). The Song of Peterloo. London: Legend Press. ISBN 978-1-78955-076-4. OCLC 1109775751.

- ^ Kaye, Jeff (2020). All The People. [S.l.]: Matador. ISBN 978-1-83859-236-3. OCLC 1115000255.

- ^ Banks, Isabella (1896). The Manchester Man, 2nd edition, with illustrations and notes. Manchester: Abel Heywood.

- ^ "Peter's Field". Sean Cooney. 2024. Archived from the original on 19 August 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bamford, Samuel (1844), Passages in the life of a radical, Heywood, ISBN 978-0-19-281413-5

- Bruton, Francis Archibald (1919), The Story of Peterloo, Manchester University Press

- Bush, Michael (2005), The Casualties of Peterloo, Carnegie Publishing, ISBN 978-1-85936-125-2

- Davis, Mary (1993), Comrade or Brother? The History of the British Labour Movement 1789–1951, Pluto Press, ISBN 978-0-7453-0761-9

- Foot, Paul (2005). The Vote: How It Was Won and How It Was Undermined. Viking. ISBN 0-670-91536-X.

- Frangopulo, N. J. (1977), Tradition in Action: The Historical Evolution of the Greater Manchester County, EP Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7158-1203-7

- Frow, Edmund; Frow, Ruth (1984), Radical Salford: Episodes in Labour History, Neil Richardson, ISBN 978-0-907511-49-6

- Glen, Robert (1984), Urban workers in the early Industrial Revolution, Croom Helm, ISBN 978-0-7099-1103-6

- Hernon, Ian (2006), Riot!: Civil Insurrection from Peterloo to the Present Day, Pluto Press, ISBN 978-0-7453-2538-5

- Jackson, Paul (2003), The Life and Music of Sir Malcolm Arnold: The Brilliant and the Dark, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-1-85928-381-3

- Krantz, Mark (2011), Rise Like Lions, Bookmarks Publications, ISBN 978-1-905192-85-4

- Marlow, Joyce (1969), The Peterloo Massacre, Rapp & Whiting, ISBN 978-0-85391-122-7

- McPhillips, K. (1977), Oldham: The Formative Years, Neil Richardson, ISBN 978-1-85216-119-4

- Pickering, Paul A.; Tyrrell, Alex (2000), The People's Bread: A History of the Anti-Corn Law League, Leicester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7185-0218-8

- Poole, Robert (2019). Peterloo: the English uprising (First ed.). Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-878346-6. OCLC 1083597363.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Poole, Steve (2000), The Politics of Regicide in England, 1760–1850, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-5035-0

- Prentice, Archibald (1853), History of the Anti-corn-law League, W. & F. G. Cash, ISBN 978-1-4326-8965-0, archived from the original on 20 August 2020, retrieved 4 May 2020

- Read, A. (1819), The Peterloo Massacre (no 1), James Wroe

- Read, Donald (1973), Peterloo: the "massacre" and its background, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-678-06791-8

- Reid, Robert (1989), The Peterloo Massacre, William Heinemann, ISBN 978-0-434-62901-5

- Vallance, Edward (2013), A Radical History of Britain: Visionaries, Rebels and Revolutionaries – the men and women who fought for our freedoms, Hachette, ISBN 978-1-85984-851-7

- Walmsley, Robert (1969), Peterloo: The Case Re-opened, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-0392-9

- Bruton, Francis Archibald (1921), Three Accounts of Peterloo

- White, Reginald J. (1957), Waterloo to Peterloo, William Heinemann Ltd

External links

[edit]- BBC Radio 4 In Our Time broadcast about the Peterloo Massacre.

- The Peterloo Massacre Memorial Campaign.

- Modern day location of the massacre Archived 8 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Original Documents covering the Peterloo Massacre from the National Archives

- Peterloo massacre

- Conflicts in 1819

- 1819 in England

- August 1819 events

- Massacres in 1819

- 1810s in Lancashire

- 19th century in Manchester

- 19th-century military history of the United Kingdom

- Massacres in England

- Massacres committed by the United Kingdom

- 19th-century mass murder in the United Kingdom

- Riots and civil disorder in Manchester

- Military history of Manchester

- Political scandals in the United Kingdom

- Protests in the United Kingdom

- Battles involving Lancashire

- Electoral reform in the United Kingdom

- St Peter's Square, Manchester