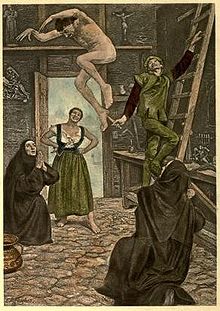

The Facetious Nights of Straparola

Night the Ninth, Sixth Fable

Watercolor by E. R. Hughes

The Italian Novelists, Volume 3

The Facetious Nights of Straparola (1550–1555; Italian: Le piacevoli notti), also known as The Nights of Straparola, is a two-volume collection of 75[1] stories by Italian author and fairy-tale collector Giovanni Francesco Straparola. Modeled after Boccaccio's Decameron, it is significant as often being called the first European storybook to contain fairy-tales;[2] it would influence later fairy-tale authors like Charles Perrault and Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.

History

[edit]The Facetious Nights of Straparola was first published in Italy between 1550–53[1] under the title Le piacevoli notti ("The Pleasant Nights") containing 74 stories. In 1555 the stories were published in a single volume in which one of the tales was replaced with two new tales, bringing the total to 75.[1] Straparola was translated into Spanish in 1583. In 1624 it was placed on the Index of Prohibited Books.[1]

The work was modeled on Boccaccio's Decameron with a frame narrative and novellas, but it took an innovative approach by also including folk and fairy tales.[1] In the frame narrative, participants of a party on the island of Murano, near Venice, tell each other stories that vary from bawdy to fantastic.[3] The narrators are mostly women, while the men, among whose ranks are included historical men of letters such as Pietro Bembo and Bernardo Cappello, listen.[1] The 74 original tales are told over 13 nights, five tales are told each night except the eighth (six tales) and the thirteenth (thirteen tales).[1] Songs and dances begin each night, and the nights end with a riddle or enigma.[1] The tales include folk and fairy-tales (about 15); Boccaccio-like novellas with themes of trickery and intrigue; and tragic and heroic stories.[1]

The 15 fairy tales were influential with later authors, some were the first recorded instances of now-famous stories, like "Puss in Boots".[1] Many of the tales were later collected or retold in Giambattista Basile’s The Tale of Tales (1634–36) and Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm's Grimm's Fairy Tales (1812–15).[1]

Fairy tales

[edit]Fairy tales that originally appeared in Nights of Straparola, with later adaptations by Giambattista Basile, Madame d'Aulnoy, Charles Perrault, Carlo Gozzi, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.[4]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Indicates sources which draw a connection between Straparola and the other folklorists for the given tale(s).

- ^ German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther, in his 2004 revision of the Aarne-Thompson Index, separated this tale under a new type: ATU 510B*, "The Princess in the Chest", wherein the princess hides inside a closet or lantern to escape from an unwanted suitor.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Nancy Canepa. "Straparola, Giovan Francesco (c. 1480–1558)" in The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales, 3-volumes, edited by Donald Haase, Greenwood Press, 2008, pages 926–27.

- ^ Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6 See page 20. The claim for earliest fairy-tale is still debated, see for example Jan M. Ziolkowski, Fairy tales from before fairy tales: the medieval Latin past of wonderful lies, University of Michigan Press, 2007. Ziolkowski examines Egbert of Liège's Latin beast poem Fecunda Ratis (The Richly Laden Ship, c. 1022/24), the earliest known version of "Little Red Riding Hood". Further info: Little Red Pentecostal Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Peter J. Leithart, July 9, 2007.

- ^ Jack Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 841, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Giovanni Francesco Straparola (2012). "Introduction". In Beecher, Donald (ed.). The Pleasant Nights. Vol. 1. Translated by Waters, W. G. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. pp. 90–92. ISBN 9781442699519.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 296. ISBN 978-951-41-0963-8.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2013). Handbuch zu den "Kinder- und Hausmärchen" der Brüder Grimm: Entstehung - Wirkung - Interpretation. Walter de Gruyter. p. 264. ISBN 9783110317633.

- ^ Le Marchand, Bérénice V. (2016). "Contes en réseaux: l'émergence du conte sur la scène littéraire européenne by Patricia Eichel-Lojkine (review)". Marvels & Tales. 30 (2): 371–373. Project MUSE 655162 ProQuest 1922870374.

- ^ Raynard, S. (1 April 2014). "Contes en reseaux: l'emergence du conte sur la scene litteraire europeenne". French Studies. 68 (2): 279–280. doi:10.1093/fs/knu045. Project MUSE 544012.

- ^ Pirovano, Donato (1 May 2008). "The Literary Fairy Tale of Giovan Francesco Straparola". Romanic Review. 99 (3–4): 281–296. doi:10.1215/26885220-99.3-4.281. ProQuest 196422641.

- ^ Giovanni Francesco Straparola (2012). "Cesarino the Dragon Slayer". In Beecher, Donald (ed.). The Pleasant Nights. Vol. 2. Translated by Waters, W. G. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. pp. 361–393. ISBN 9781442699533.

Further reading

[edit]- Ruth B. Bottigheimer, Fairy Godfather: Straparola, Venice, and the Fairy Tale Tradition (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

External links

[edit]- The Nights of Straparola, trans. W.G.Waters 1894. Scanned original color illustrated editions.

- The Italian Novelists (vol. 1–4), trans. W.G.Waters 1901–04. Scanned original color illustrated editions. Note: this edition differs slightly in content from the 1894 edition.

- SurLaLune Fairy Tale Pages: The Facetious Nights of Straparola