Mayerling incident

48°02′49″N 16°05′54″E / 48.04694°N 16.09833°E

The Mayerling incident is the series of events surrounding the apparent murder–suicide pact of Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria, and his lover, baroness Mary Vetsera. They were found dead on 30 January 1889 in an imperial hunting lodge in Mayerling. Rudolf, who was married to Princess Stéphanie of Belgium, was the only son of Emperor Franz Joseph and Empress Elisabeth, and was heir apparent to the throne of Austria-Hungary.

Rudolf's mistress was the daughter of Albin von Vetsera, a diplomat at the Austrian court. Albin had been created a Freiherr (Baron) in 1870. The bodies of the 30-year-old Rudolf and the 17-year-old Mary were discovered in the Imperial hunting lodge at Mayerling in the Vienna Woods, 26.6 kilometres (16.5 mi) southwest of the capital, on the morning of 30 January 1889.[1]

The death of the Crown Prince interrupted the security inherent in the direct line of Habsburg dynastic succession. As Rudolf had no son, the succession passed to Franz Joseph's brother, Archduke Karl Ludwig, and his eldest son, Archduke Franz Ferdinand.[1]

This destabilisation endangered the growing reconciliation between the Austrian and Hungarian factions of the empire. Succeeding developments led to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie by Gavrilo Princip, a Yugoslav nationalist and ethnic Serb, at Sarajevo in June 1914, and the July Crisis that led to the start of the First World War.[2]

Suicide

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2019) |

By 1889, many people at the Imperial Court, including Rudolf's parents and his wife, Stéphanie, knew that Rudolf and Mary were having an affair. His marriage to Stéphanie was not a particularly happy one and had resulted in the birth of only one child, a daughter called Elisabeth, known as Erzsi. Rudolf had infected his wife with syphilis, rendering her unable to have more children.[3]

On 29 January 1889, Franz Joseph and Elisabeth gave a family dinner party before leaving for Buda, in Hungary, on 31 January. Rudolf excused himself, claiming to be indisposed. He had arranged for a day's shooting at Mayerling hunting lodge early on the morning of the 30th, but when his valet Loschek went to call him, there was no answer. Joseph Hoyos, the Archduke's hunting companion, joined in, with no response. They tried to force the door, but it would not give.

Finally, Loschek smashed in a door panel with a hammer so that he could put his hand through to open the door from the inside. He found the room shuttered and half-dark. Rudolf was found sitting (by some accounts, lying) motionless by the side of the bed, leaning forward and bleeding from the mouth. Before him on the bedside table stood a glass and a mirror. Without closer examination in the poor light, Loschek assumed that the Crown Prince had drunk poison from the glass since he knew strychnine caused bleeding. On the bed lay the body of Mary Freiin von Vetsera; rigor mortis had already set in.[4]

Hoyos did not look any closer, but rushed to the station and took a special train to Vienna. He hurried to the Emperor's Adjutant General, Paar, and requested he break the news to the Emperor. The stifling protocol that characterised every movement in the Hofburg controlled the notification process. Paar protested that only the Empress could break such catastrophic news to the Emperor. Baron Nopcsa, Controller of the Empress's Household, was summoned. He, in turn, sent for Ida Ferenczy, Empress Elisabeth's favourite Hungarian lady-in-waiting, to determine how Her Imperial Majesty should be informed.

Elisabeth was at her Greek lesson and was impatient at the interruption. Her lips white, Ferenczy announced that Baron Nopcsa had urgent news. Elisabeth replied that Nopcsa must wait and come back later. Ferenczy insisted that Nopcsa must be received immediately, finally adding that there was grave news about the Crown Prince. This account comes from Ferenczy herself and Archduchess Marie Valerie, to whom Elisabeth dictated her memory of the incident, in addition to the description in her diary.[5]

Ferenczy entered the room again to find Elisabeth distraught and weeping uncontrollably. The Emperor appeared outside her apartments and was forced to wait there with Nopcsa, who was controlling himself only with great effort. The Empress broke the news to her husband in private.

The Minister for Police was summoned and the national security services sealed off the Imperial hunting lodge and the surrounding area.

Attempted cover-up

[edit]Eduard von Taaffe, Ministerpräsident (Minister-President) of Cisleithania, issued a statement at noon on behalf of the Emperor that Rudolf had died "due to a rupture of an aneurysm of the heart". The Imperial Family and Imperial Court were still under the impression that he had been poisoned. It appears that even Mary's mother, Helene von Vetsera, initially believed this.

The Imperial Court medical commission, headed by Dr. Widerhofer, arrived in Mayerling that afternoon and established a more accurate cause of death. Widerhofer made his report to the Emperor at 6 a.m. the following morning. The official gazette of Vienna still reported the original story that day: "His Royal and Imperial Highness, Crown Prince Archduke Rudolf, died yesterday at his hunting lodge of Mayerling, near Baden, from the rupture of an aneurysm of the heart."[6]

They attempted to state that Vetsera had died on her way to Venice, having her uncles prop up her body with a broomstick to cover-up the double suicide as they left the lodge. Vetsera was quickly buried with other suicides, and the imperial court refused to let Vetsera's mother see her daughter's grave for over two months after the burial.[7]

Foreign correspondents descended on Mayerling and soon learned that Rudolf's mistress was implicated in his death. This first official version of a heart attack was quickly dropped. At that stage, the "heart failure" version was amended. It was announced that the Crown Prince had first shot the baroness in a suicide pact and sat by her body for several hours before shooting himself. Rudolf and the Emperor were known to have recently had a violent argument, with Franz Joseph demanding that his son end the liaison with his teenage mistress. The police closed their investigations with surprising haste, in apparent response to the Emperor's wishes.

Franz Joseph did everything in his power to get the Church's blessing for Rudolf's burial in the Imperial Crypt. This would have been impossible had the Crown Prince deliberately committed murder and suicide. The Vatican issued a special dispensation declaring that Rudolf had been in a state of "mental imbalance", and he now lies with 137 other Habsburgs in the Imperial Crypt at the Church of the Capuchins in Vienna. However, Rudolf had requested in his farewell note to his mother that he be buried next to Mary Vetsera in Alland. Elisabeth was haunted by this, and visited the Capuchin Crypt, hoping that Rudolf's spirit would visit her and communicate his wishes.[8] The dossier on the investigations and related actions were not deposited in the state archives, as they would typically have been.[9]

The story that Rudolf had violently quarreled with the Emperor over his liaison with Freiin von Vetsera may have been spread by agents of Germany's Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, who had little love for the politically liberal Rudolf. It was certainly doubted by many of Rudolf's close relatives, who knew the Chancellor personally.

German Empress Victoria wrote:

Yesterday Prince Bismarck came. It was a bitter pill to me to have to receive him after all that has taken place and with all that is going on. He talked a great deal about Rudolf, and said that a scene with the Emperor [of Austria] had taken place, according to Reuss' account. Perhaps Reuss [the German Ambassador to Austria] was wrong. I should think [it] very likely. [9 April 1889][10]

She then wrote to her mother, Queen Victoria:

... I have heard different things about poor Rudolf which may perhaps interest you. Prince Bismarck told me that the violent scenes and altercations between the Emperor and Rudolf had been the cause of Rudolf's suicide. I replied that I had heard this much doubted, upon which he said Reuss had written it and it was so! He would send me the despatch to read if I liked, but I have declined. I did not say what I thought, which is that for thirty years I have had the experience of how many lies Prince Bismarck's diplomatic agents (with some exceptions) have written him, and therefore I usually disbelieve what they write completely, unless I know them to be honest and trustworthy men. Szechenyi, the Ambassador at Berlin, whom we know very well, tells me that there had been no scenes with the Emperor, who said to Szechenyi: 'This is the first vexation my son has caused me.' I give you the news for what it is worth. General Loe heard from Austrian sources that the catastrophe was not premeditated for that day! but that the young lady had destroyed herself and, seeing that, Rudolf thought there was nothing else left to him, and that he had killed himself with a Förster Gewehr [hunting rifle] which he stood on the ground and then trod on the trigger. Loe considers, as I do, poor Rudolf's death a terrible misfortune. The Chancellor, I think, does not deplore it, and did not like him! [April 20, 1889][10]

Allegations of a double murder masked as a murder–suicide have also been made. In a series of interviews with the Viennese tabloid newspaper Kronen Zeitung, the Empress Zita, who was not born until three years after the incident, expressed her belief that the deaths of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria and his mistress were not a double suicide, but rather a murder by French agents sent by Georges Clemenceau.[11][12]

Aftermath

[edit]The death of Rudolf caused a dynastic crisis. As Rudolf was the only son of Franz Joseph, the emperor's brother, Karl Ludwig, became heir-presumptive to Austria-Hungary. He renounced his succession rights a few days later in favour of his eldest son, Franz Ferdinand.[13]

After Franz Ferdinand's assassination in 1914, Franz Ferdinand's nephew (and Karl Ludwig's grandson), Karl, became the heir-presumptive. Karl would ultimately succeed his great-uncle as Emperor Karl I in 1916.

Motivation

[edit]

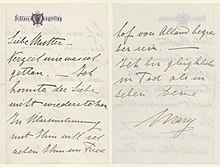

In July 2015, the Austrian National Library issued copies of Vetsera's letters of farewell to her mother and other family members.[14] These letters, previously believed to be lost or destroyed, were found in a safe deposit box in an Austrian bank, where they had been deposited in 1926. The letters—written in Mayerling shortly before the deaths—state clearly and unambiguously that Vetsera was preparing to commit suicide alongside Rudolf:

Theories

[edit]Brigitte Hamann, in her book Rudolf, Crown Prince and Rebel, states Rudolf had first proposed a double suicide to a prominent courtesan, Mizzi Kaspar.[16][17][18] It was after she refused that Rudolf proposed the death pact with the more susceptible Vetsera. Hamann, in an interview, argued Rudolf "was a poetic young man and brooded a lot. He was ill with syphilis and felt guilty that he had infected his wife."[16] This is the theory most widely accepted by historians.[18]

Another theory is the exacerbation of his mental health struggles from abuse during his childhood culminated in the suicide pact. He became more unstable over the course of his marriage and varied affairs, and offered the suicide pact to a variety of people. Vetsera was only 17, and believed she could not live without Rudolf, leading to the joint suicide (with Rudolf killing Vetsera several hours before killing himself).[7]

Gerd Holler argues in his book Mayerling--New Documents on the Tragedy 100 Years Afterward that Mary was three months pregnant with Rudolf's child. Rudolf arranged an abortion for Mary, who died in the process. Rudolf then committed suicide.[16] Lucy Coatman believes this is not possible, citing one of Mary's letters to Hermine Tobis as her source: "'We both lost our heads', Mary wrote to Hermine, 'and I became a woman! Now we belong to each other in body and soul.' Her letter makes it clear this was Mary's first sexual experience. This disproves the abortion theory (her pregnancy would not have been evident by the time of their deaths) [...]."[19]

Clemens M. Gruber, in a piece called The Fateful Days of Mayerling, argues Rudolf died in a drinking brawl. In Gruber's story, Vetsera's relatives forced their way into the lodge and Rudolf drew a revolver, accidentally shooting the baroness. He was then killed by one of her relatives.[16]

Exhumations and forensic evidence

[edit]Freiin von Vetsera's body was spirited out of Mayerling and interred in the graveyard at Heiligenkreuz. In 1946, occupying Soviet troops dislodged the granite plate covering the grave and broke into Vetsera's coffin in the graveyard, perhaps hoping to loot it of jewels. This break-in was not discovered until 1955 when the Red Army withdrew from Austria per the Austrian State Treaty.

In 1959, a young physician named Gerd Holler, stationed in the area, accompanied by a member of the Vetsera family and specialists in funereal preservation, inspected her remains. Holler carefully examined the skull and other bones for traces of a bullet hole but stated that he found no such evidence. Intrigued, Holler claimed he petitioned the Vatican to inspect their 1889 archives of the affair, where the papal nuncio's investigation had concluded that only one bullet was fired. Lacking forensic evidence of a second bullet, Holler advanced the theory that Vetsera died accidentally, probably as the result of an abortion, and it was Rudolf who consequently shot himself.[20] Holler witnessed the body's re-interment in a new coffin in 1959.

In 1991, Vetsera's remains were disturbed again, this time by Helmut Flatzelsteiner, a Linz furniture dealer who was obsessed with the Mayerling affair. Initial reports were that her bones were strewn around the churchyard for the authorities to retrieve. But Flatzelsteiner removed them at night for a private forensic examination at his expense, which finally took place in February 1993.[21]

Flatzelsteiner told the examiners that the remains were those of a relative killed some 100 years ago, who had possibly been shot in the head or stabbed. One expert thought this might be possible, but since the skull was not only in a state of disintegration but was actually incomplete, this could not be confirmed. Flatzelsteiner then approached a journalist at the Kronen Zeitung to sell both the story and Vetsera's skeleton. That these were Vetsera's remains was confirmed through forensic examination. The body was re-interred in the original grave in October 1993,[22] and after a court case, Flatzelsteiner paid the abbey €2000 for damages.[23]

In the media

[edit]The Mayerling affair has been dramatized in:

Literature

[edit]- A Nervous Splendor: Vienna, 1888–1889 – a work of popular history by Frederic Morton[24]

- Mayerling: The Love and Tragedy of a Crown Prince – a novel by Jean Schopfer (pseudonym of Claude Anet).[25]

- Angel's Coffin (Ave Maria/Tenshi no Hitsugi) – 2000 Japanese manga by You Higuri.[26]

Stage

[edit]- Marinka – 1945 premier; operetta by Hungarian composer Emmerich Kálmán; libretto by George Marion, Jr. and Karl Farkas, lyrics by George Marion, Jr.

- Mayerling – 1957 opera by Barbara Giuranna

- Mayerling – 1978 ballet created by Kenneth MacMillan

- Elisabeth – 1992 musical; book/lyrics by Michael Kunze, music by Sylvester Levay. Incident is dramatized as a stylized dance sequence

- Mayerling : Requiem einer Liebe – 2006 German crossover opera by Ricardo Urbetsch, lyrics by Siegfried Carl[27]

- Rudolf – 2006 musical by Frank Wildhorn and Steve Cuden; premiered 26 May 2006: Operett Színház, Budapest

- Rudolf – 2011 play by David Logan dramatises the last few weeks of the life of Crown Prince Rudolf[28]

- "Utakatano Koi" : play by Takarazuka Reveu 1983, 1984, 1993, 1994, 1999, 2000, 2006, 2013, 2018, 2023

Film

[edit]- Tragedy in the House of Habsburg – 1924 German silent film directed by Alexander Korda

- The Fate of the House of Habsburg – 1928 German silent film directed by Rolf Raffé

- Mayerling – 1936 French film directed by Anatole Litvak

- De Mayerling à Sarajevo – 1940 French film directed by Max Ophüls

- Le Secret de Mayerling – 1949 French film directed by Jean Delannoy

- Kronprinz Rudolfs letzte Liebe - 1955 Austrian film directed by Rudolf Jugert

- Mayerling – 1968 British/French film (in English) directed by Terence Young

- Private Vices, Public Virtues (Vizi privati, pubbliche virtù) – 1976 Italian/Yugoslavian film (in Italian) directed by Miklós Jancsó

- The Illusionist – 2006 American film directed by Neil Burger; includes a fictionalized depiction of the incident

Radio

[edit]- The Story of Mayerling – 1950 American radio play on Theater of Romance (CBS); episode 244: August 1, 1950 [29]

- Mayerling Revisted – 1977 American radio play on CBS Radio Mystery Theater; episode 0648: May 16, 1977. Modern frame story of the contemporary events.[30]

Television

[edit]- Mayerling – 1957 American television episode of Producers' Showcase (released theatrically in Europe) directed by Anatole Litvak

- "Requiem For A Crown Prince" – 1974 British television series Fall of Eagles; episode 4

- Kronprinz Rudolfs letzte Liebe (US release titled The Crown Prince) – 2006 Austrian TV film directed by Robert Dornhelm

See also

[edit]- Countess Marie Larisch von Moennich – a go-between for her cousin Rudolf and her friend Mary Vetsera

- Prince Leopold Clement of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1878–1916), Rudolf's nephew, murdered by his mistress who then committed suicide

References

[edit]- ^ a b Palmer, A. Twilight of the Habsburgs: The Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph. Atlantic Monthly Press. pp. 246–253

- ^ Spitznagel, Mark (2013). The Dao of Capital: Austrian Investing in a Distorted World. John Wiley & Sons. p. 95. ISBN 9781118416679.

- ^ "1889 Hapsburg Tragedy at Mayerling : 'Love Deaths' Remain Fascinating". Los Angeles Times. 19 March 1989.

- ^ Corti, E. (1936). Elizabeth, Empress of Austria. Yale University Press. p. 391.

- ^ Corti, E. (1936). Elizabeth, Empress of Austria. Yale University Press. p. 392.

- ^ Emerson, E. (1902). A History of the Nineteenth Century, Year by Year. 3. New York: P.F. Collier and Son. p. 1695.

- ^ a b "Love is Dead | History Today".

- ^ Coatman, Lucy (27 January 2022). "Mater Dolorosa: Elisabeth in the Aftermath of Mayerling". Team Queens. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Ronay, Gabriel, Death in the Vienna woods

- ^ a b Ponsonby, Frederick, ed., Letters of the Empress Frederick, Macmillan and Co., Ltd., 1929. p. 370

- ^ Brook-Shepherd, G. (1991). The Last Empress – The Life and Times of Zita of Austria-Hungary 1893–1989. Harper-Collins. ISBN 0-00-215861-2.

- ^ Bassett, R. (2015). For God and Kaiser: The Imperial Austrian Army, 1619–1918. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300213107. p.633.

- ^ "The Crown Prince's Successor". The New York Times. 2 February 1889.

- ^ "Mary Vetsera's suicide letters found". The Local. 31 July 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Bankers found this 'sensational' love note in a vault that's been untouched since 1926". Business Insider. 31 July 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d Tuohy, William (19 March 1989). "1889 Hapsburg Tragedy at Mayerling : 'Love Deaths' Remain Fascinating". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ von Hornau, Phillipp (2012). Wien ist anders - Ist Wien anders? (in German). epubli. p. 41.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Schmemann, Serge (10 March 1989). "Mayerling Journal; Lurid Truth and Lurid Legend: A Hapsburg Tale". New York Times.

- ^ "Love Is Dead | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Holler, G. (1983). Mayerling: The Solution to the Puzzle. Molden.

- ^ Pannell, R. (November 2008). "Murder at Mayerling?" History Today. 58 (11). p. 67.

- ^ Markus, Georg, Crime at Mayerling: The Life and Death of Mary Vetsera: With New Expert Opinions Following the Desecration of Her Grave, Ariadne Press, 1995

- ^ "Leichnam von Mary Vetsera gestohlen – oesterreich.ORF.at". Ktnv1.orf.at. 19 November 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ Morton, Frederic (1979). A Nervous Splendor : Vienna, 1888/1889 (1st ed.). Little, Brown. ISBN 9780316585323.

- ^ Anet, Claude (1932). Mayerling: The Love and Tragedy of a Crown Prince. Hutchinson.

- ^ "Go! Comi, "Angel's Nest."". Gocomi.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Mayerling * Requiem einer Liebe – Home". Mayerling-opera.de. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ Logan, David (2011). Rudolf: a play in two acts. Brisbane Dramatic Arts Company. ISBN 9780980655100. Retrieved 8 March 2019 – via National Library of Australia | Catalogue.

- ^ Goldin, J. David. "Romance". radiogoldindex.com.

- ^ Gordon Payton; Martin Grams, Jr. (2015). The CBS Radio Mystery Theater: An Episode Guide and Handbook to Nine Years of Broadcasting, 1974–1982 (illustrated, reprint ed.). McFarland. p. 207. ISBN 9780786492282.

Further reading

[edit]- Barkeley, Richard. (1958). The Road to Mayerling: Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolph of Austria. London: Macmillan.

- Franzel, Emil. (1974). Crown Prince Rudolph and the Mayerling Tragedy: Fact and Fiction. Vienna: V. Herold.

- Graves, Armgaard Karl (2019). The Secrets of the Hohenzollerns. Creative Media Partners. ISBN 9780530575254. – Total pages: 266

- Judtmann, Fritz. (1971). Mayerling: The Facts Behind the Legend. London: Harrap.

- King, Greg and Wilson, Penny. (2017). Twilight of Empire: The Tragedy at Mayerling and the End of the Habsburgs, New York: St. Martin's Press

- Listowel, Judith. (1978). A Habsburg Tragedy. Crown Prince Rudolf. London: Ascent.

- Lonyay, Károly. (1949). Rudolph: The Tragedy of Mayerling. New York: Scribner.

- Wolfson, Victor. (1969). The Mayerling Murder. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.