Irish National Land League

Irish National Land League Conradh na Talún | |

|---|---|

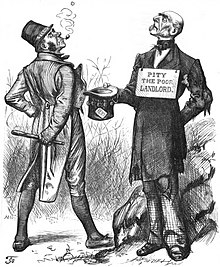

Irish landlord reduced to begging for rent, 1880 caricature | |

| Abbreviation | INLL |

| President | Charles Stewart Parnell |

| Secretary | Andrew Kettle Michael Davitt Thomas Brennan |

| Founded | 21 October 1879 |

| Dissolved | 17 October 1882 |

| Succeeded by | Irish National League |

| Ideology | Agrarianism Irish nationalism |

| Political position | Centre-left |

The Irish National Land League (Irish: Conradh na Talún), also known as the Land League, was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which organised tenant farmers in their resistance to exactions of landowners. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmers to own the land they worked on. The period of the Land League's agitation is known as the Land War. Historian R. F. Foster argues that in the countryside the Land League "reinforced the politicization of rural Catholic nationalist Ireland, partly by defining that identity against urbanization, landlordism, Englishness and—implicitly—Protestantism."[1] Foster adds that about a third of the activists were Catholic priests, and Archbishop Thomas Croke was one of its most influential champions.[2]

Background

[edit]

Following the founding meeting of the Mayo Tenants Defence Association in Castlebar, County Mayo on 26 October 1878 the demand for The Land of Ireland for the people of Ireland was reported in the Connaught Telegraph 2 November 1878.

The first of many "monster meetings" of tenant farmers was held in Irishtown near Claremorris on 20 April 1879, with an estimated turnout of 15,000 to 20,000 people. This meeting was addressed by James Daly (who presided), John O'Connor Power, John Ferguson, Thomas Brennan, and J. J. Louden.

The Connaught Telegraph's report of the meeting in its edition of 26 April 1879 began:

Since the days of O'Connell a larger public demonstration has not been witnessed than that of Sunday last. About 1 o'clock the monster procession started from Claremorris, headed by several thousand men on foot – the men of each district wearing a laurel leaf or green ribbon in hat or coat to distinguish the several contingents. At 11 o'clock a monster contingent of tenant farmers on horseback drew up in front of Hughes's hotel, showing discipline and order that a cavalry regiment might feel proud of. They were led on in sections, each having a marshal who kept his troops well in hand. Messrs. P.W. Nally, J.W. Nally, H. French, and M. Griffin, wearing green and gold sashes, led on their different sections, who rode two deep, occupying, at least, over an Irish mile of the road. Next followed a train of carriages, brakes, cares, etc. led on by Mr. Martin Hughes, the spirited hotel proprietor, driving a pair of rare black ponies to a phæton, taking Messrs. J.J. Louden and J. Daly. Next came Messrs. O'Connor, J. Ferguson, and Thomas Brennan in a covered carriage, followed by at least 500 vehicles from the neighbouring towns. On passing through Ballindine the sight was truly imposing, the endless train directing its course to Irishtown – a neat little hamlet on the boundaries of Mayo, Roscommon, and Galway.

Evolving out of this a number of local land league organisations were set up to work against the excessive rents being demanded by landlords throughout Ireland, but especially in Mayo and surrounding counties.

From 1874 agricultural prices in Europe had dropped, followed by some bad harvests due to wet weather during the Long Depression. The effect by 1878 was that many Irish farmers were unable to pay the rents that they had agreed, particularly in the poorer and wetter parts of Connacht. The localised 1879 Famine added to the misery. Unlike many other parts of Europe, the Irish land tenure system was inflexible in times of economic hardship.

In January 1874, there had been an attempt to revive what the Young Irelander Charles Gavan Duffy had hailed as the "League of North and South".[3]: 297 In 1852, the Tenant Right League had helped return 48 MPs to Westminster where they briefly cohered as the Independent Irish Party. The initiative in 1874 came from largely Presbyterian tenant righters in the north. The Route Tenants Defence Association (Ballymoney) organised an all-Ireland National Tenants Rights conference in Belfast.[4] In addition to the "Three F's" (fair rent fixity of tenure, and free sales), resolutions called for loans to facilitate tenant purchase of land and for breaking the landlord monopoly on local government.[5][full citation needed][6]

Once again there was a determination to organise parliamentary constituencies so as to return Members pledged to tenant rights.[6] But, as in the 1850s, the "shared dislike for, or hostility to, landlords, and a common desire for improved tenurial terms" could not overcome the sectarian-aligned division over Irish self-government between the Repeal Association, or now in 1874 the Home Rule League, parliamentary candidates who adopted the tenant programme in the south and west, and the majority of the Liberals who championed it in the north.[3]: 298 [6]

League founded

[edit]

The Irish National Land League was founded at the Imperial Hotel in Castlebar, the County town of Mayo, on 21 October 1879. At that meeting Charles Stewart Parnell, the prominent Home Rule Member of Parliament, was elected president of the league. Andrew Kettle, Michael Davitt and Thomas Brennan were appointed as honorary secretaries. This united practically in a single organisation all the different strands of land agitation and tenant rights movements on the nationalist side of the increasingly frozen sectarian-political divide in Ireland.[3]: 320

The key motion at the Dublin meeting was proposed by Parnell. It proposed that the objectives of the League were:[7]

... first, to bring about a reduction of rack-rents; second, to facilitate the obtaining of the ownership of the soil by the occupiers [and that these] ... can be best attained by promoting organisation among the tenant-farmers; by defending those who may be threatened with eviction for refusing to pay unjust rents; by facilitating the working of the Bright clauses of the Irish Land Act during the winter; and by obtaining such reforms in the laws relating to land as will enable every tenant to become owner of his holding by paying a fair rent for a limited number of years.

Parnell, Davitt, John Dillon and others then went to the United States to raise funds for the League with spectacular results. Branches were also set up in Scotland, where the Crofters Party imitated the League and secured a reforming Act in 1886.

The government had introduced the first Land Act in 1870, which proved largely ineffective. It was followed by further marginally more effective Irish Land Acts of 1880 and 1881. These established a Land Commission that started to reduce some rents. Parnell together with all of his party lieutenants, including Father Eugene Sheehy known as "the Land League priest", went into a bitter verbal offensive and were imprisoned in October 1881 under the Irish Coercion Act in Kilmainham Jail for "sabotaging the Land Act", from where the No-Rent Manifesto was issued, calling for a national tenant farmer rent strike until "constitutional liberties" were restored and the prisoners freed. It had a modest success In Ireland, and mobilized financial and political support from the Irish Diaspora.[8]

Although the League discouraged violence, agrarian crimes increased widely. Typically a rent strike would be followed by eviction by the police and the bailiffs. Tenants who continued to pay the rent would be subject to a boycott, or as it was contemporaneously described in the US press, an "excommunication" by local League members.[9] Where cases went to court, witnesses would change their stories, resulting in an unworkable legal system. This in turn led on to stronger criminal laws being passed that were described by the League as "Coercion Acts".

The bitterness that developed helped Parnell later in his Home Rule campaign. Davitt's views as seen in his famous slogan: "The land of Ireland for the people of Ireland" was aimed at strengthening the hold on the land by the peasant Irish at the expense of the alien landowners.[10] In reaction to such appeals, and to the Phoenix Park murders to which Parnell's unionist opponents sought to associate him, what limited Protestant support that the League had enjoyed in the north fell away.[11]

Parnell aimed to harness the emotive element, but he and his party were strictly constitutional. He envisioned tenant farmers as potential freeholders of the land they had rented.

In the United States

[edit]The Land League had an equivalent organization in the United States, which raised hundreds of thousands of dollars both for famine relief and also for political action.[12] The Clan na Gael attempted to infiltrate the Land League, with limited success.[13]

Land war

[edit]

From 1879 to 1882, the "Land War" in pursuance of the "Three Fs" (Fair Rent, Fixity of Tenure and Free Sale) first demanded by the Tenant Right League in 1850, was fought in earnest. The League organised resistance to evictions, reductions in rents and aided the work of relief agencies. Landlords' attempts to evict tenants led to violence, but the Land League denounced excessive violence and destruction.

Withholding of rent led to evictions until "Ashbourne's Act" in 1885 made it unprofitable for most landlords to evict.[14] By then agricultural prices had made a recovery, and rents had been fixed and could be reviewed downwards, but tenants found that holding out communally was the best option. Critics noted that the poorer sub-tenants were still expected to pay their rents to tenant farmers.

The widespread upheavals and extensive evictions were accompanied by several years of bad weather and poor harvests when the tenant farmers who were unable to pay the full arrears of rents resorted to a rent strike. A renewed Land War was waged under the Plan of Campaign from 1886 up until 1892 during which the League decided on a fair rent and then encouraged its members to offer this rent to the landlords. If this was refused, then the rent would be paid by tenants to the League and the landlord would not receive any money until he accepted a discount.

The first target, ironically, was a member of the Catholic clergy, Canon Ulick Burke of Knock, who was eventually induced to reduce his rents by 25%. Many landlords resisted these tactics, often violently and there were deaths on either side of the dispute. The Royal Irish Constabulary, the national armed police force, were charged with upholding the law and protecting both landlord and tenant against violence. Originally, the movement cut across some sectarian boundaries, with some meetings held in Orange halls in Ulster, but the tenancy system in effect there Ulster Custom was quite different and fairer to tenants and support drifted away.

As a result of the Land War, the Irish National Land League was suppressed by the authorities.[citation needed] In October 1882, as its successor Parnell founded the Irish National League to campaign on broader issues including Home Rule.[15] Many of the Scottish members formed the Scottish Land Restoration League. In 1881, the League started publishing United Ireland, a weekly newspaper edited by William O'Brien, which continued until 1898.

Outcomes

[edit]Within decades of the league's foundation, through the efforts of William O'Brien and George Wyndham (a descendant of Lord Edward FitzGerald), the 1902 Land Conference produced the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903 which allowed Irish tenant farmers to buy out their freeholds with UK government loans over 68 years through the Land Commission (an arrangement that has never been possible in Britain itself). For agricultural labourers, D.D. Sheehan and the Irish Land and Labour Association secured their demands from the Liberal government elected in 1905 to pass the Labourers (Ireland) Act 1906, and the Labourers (Ireland) Act 1911, which paid County Councils to build over 40,000 new rural cottages, each on an acre of land. By 1914, 75% of occupiers were buying out their landlords, mostly under the two Acts. In all, under the pre-UK Land Acts over 316,000 tenants purchased their holdings amounting to 15 million acres (61,000 km2) out of a total of 20 million acres (81,000 km2) in the country.[16] Sometimes the holdings were described as "uneconomic", but the overall sense of social justice was manifest.

The major land reforms came when Parliament passed laws in 1870, 1881, 1903 and 1909 that enabled most tenant farmers to purchase their lands, and lowered the rents of the others.[17] From 1870 and as a result of the Land War agitations and the Plan of Campaign of the 1880s, various British governments introduced a series of Irish Land Acts. William O'Brien played a leading role in the 1902 Land Conference to pave the way for the most advanced social legislation in Ireland since the Union, the Wyndham Land Purchase Act of 1903. This Act set the conditions for the break-up of large estates and gradually devolved to rural landholders and tenants' ownership of the lands. It effectively ended the era of the absentee landlord, finally resolving the Irish Land Question.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ R. F. Foster, Modern Ireland, 1600–1972 (1988) p. 415.

- ^ Foster, Modern Ireland, 1600–1972 (1988) pp. 417–18.

- ^ a b c Bartlett, Thomas (2010). Ireland, a History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521197205.

- ^ Courtney, Roger (2013). Dissenting Voices: Rediscovering the Irish Progressive Presbyterian Tradition. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. p. 225. ISBN 9781909556065. OCLC 890011817.

- ^ The Nation. 24 January 1874.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c McCaffrey, Lawrence J. (1962). "Irish Federalism in the 1870's: A Study in Conservative Nationalism". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 52 (6): (1–58), 16, 18. doi:10.2307/1005883. hdl:2027/mdp.49015000248188. ISSN 0065-9746. JSTOR 1005883.

- ^ "Image, Land League Committee Meeting, Dublin, 1864". Victorian Collections. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ Richard Schneirov (1998). Labor and Urban Politics: Class Conflict and the Origins of Modern Liberalism in Chicago, 1864-97. University of Illinois Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780252066764.

- ^ "The sun., December 29, 1880, Image 3 About The sun. (New York N.Y.) 1833-1916". Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Sidney Webb (1908). The Basis and Policy of Socialism. A. C. Fifield. p. 72.

- ^ Bardon, Jonathan (1992). A History of Ulster. Belfast: The Blackstaff Press. p. 371. ISBN 0856404764.

- ^ Janis 2015, pp. 41, 65.

- ^ Janis 2015, p. 64.

- ^ Ireland as It Is and as It Would Be Under Home Rule. 1893. p. 400.

- ^ Michael Davitt (1904). The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland: Or, The Story of the Land League Revolution. p. 372. ISBN 9780716500438.

- ^ Ferriter, Diarmaid: "The Transformation of Ireland, 1900–2000", Profile Books, London (2004), pp. 62–63, 159 (ISBN 1 86197 443-4)

- ^ Timothy W. Guinnane and Ronald I. Miller. "The Limits to Land Reform: The Land Acts in Ireland, 1870–1909*." Economic Development and Cultural Change 45#3 (1997): 591-612. online Archived 17 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

Print sources

[edit]- Janis, Ely M. (2015). A Greater Ireland: The Land League and Transatlantic Nationalism in Gilded Age America. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299301248.

Further reading

[edit]- Bull, Philip (1996). Land, Politics and Nationalism: A Study of the Irish Land Question. Gill & Macmillan.

- Cashman, D. B. & Davitt, Michael (1881). The Life of Michael Davitt and the Secret History of The Land League

- Clark, Sam (1971). "The social composition of the Land League". Irish Historical Studies: 447–469. JSTOR 30005304.

- Clark, Samuel, and James S. Donnelly (1983). Irish peasants: violence & political unrest, 1780–1914. Manchester University Press.

- Davitt, Michael. The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland. ISBN 1-59107-031-7.

- Michael Davitt (1882), The land league proposal: a statement for honest and thoughtful men (1st ed.), Glasgow: Cameron and Ferguson, Wikidata Q19091811

- Gross, David (ed.). We Won’t Pay!: A Tax Resistance Reader. ISBN 1-4348-9825-3. pp. 263–266.

- Green, James J. (1949). "American Catholics and the Irish Land League, 1879-1882" Catholic Historical Review: 19-42. JSTOR 25014992.

- Jordan, Donald (1998). "The Irish National League and the 'Unwritten Law': Rural Protest and Nation-Building in Ireland 1882-1890". Past and Present: 146–171. JSTOR 651224.

- William Henry Hurlbert. Ireland Under Coercion Vol. 1 (1888); Vol. 2. Analysis by a Catholic Irish-American.

- Linton, E. Lynn (1890). About Ireland. (Anti-League analysis by an English journalist).

- Stanford, Jane (2011). That Irishman: The Life and Times of John O'Connor Power. History Press Ireland. ISBN 978-1-84588-698-1

- TeBrake, Janet K. (1992). "Irish Peasant Women in Revolt: The Land League Years". Irish Historical Studies 63–80. JSTOR 30008005.