Galilee

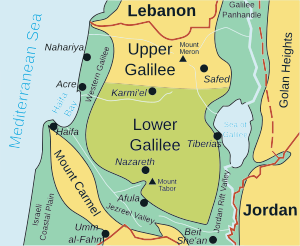

Galilee (/ˈɡælɪliː/;[1] Hebrew: הַגָּלִיל, romanized: hagGālīl; Latin: Galilaea;[2] Arabic: الجليل, romanized: al-Jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon consisting of two parts: the Upper Galilee (הגליל העליון, ha-Galil ha-Elyon; الجليل الأعلى, al-Jalīl al-Aʿlā) and the Lower Galilee (גליל תחתון, Galil Taḫton; الجليل الأسفل, al-Jalīl al-Asfal).

Galilee encompasses the area north of the Mount Carmel-Mount Gilboa ridge and south of the east-west section of the Litani River. It extends from the Israeli coastal plain and the shores of the Mediterranean Sea with Acre in the west, to the Jordan Valley to the east; and from the Litani in the north plus a piece bordering on the Golan Heights to Dan at the base of Mount Hermon in the northeast, to Mount Carmel and Mount Gilboa in the south.

It includes the plains of the Jezreel Valley north of Jenin and the Beit She'an Valley, the Sea of Galilee, and the Hula Valley.

Etymology

The region's Hebrew name is Hebrew: גָּלִיל, romanized: gālíl, meaning 'district' or 'circle'.[3] The Hebrew form used in Isaiah 8:23 (Isaiah 9:1 in the Christian Old Testament) is in the construct state, leading to Hebrew: גְּלִיל הַגּוֹיִם, romanized: gəlil haggóyim "Galilee of the nations", which refers to gentiles who settled there at the time the book was written, either by their own volition or as a result of the resettlement policy of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[3]

Borders and geography

The borders of Galilee, split into Upper Galilee and Lower Galilee, were described by Josephus in his The Jewish War:[4]

Now Phoenicia and Syria encompass about the Galilees, which are two, and called the Upper Galilee and the Lower. They are bounded toward the sun-setting, with the borders of the territory belonging to Ptolemais, and by Carmel; which mountain had formerly belonged to the Galileans, but now belonged to the Tyrians; to which mountain adjoins Gaba, which is called the City of Horsemen, because those horsemen that were dismissed by Herod the king dwelt therein; they are bounded on the south with Samaria and Scythopolis, as far as the river Jordan; on the east with Hippeae and Gadaris, and also with Ganlonitis, and the borders of the kingdom of Agrippa; its northern parts are bounded by Tyre, and the country of the Tyrians. As for that Galilee which is called the Lower, it extends in length from Tiberias to Zabulon, and of the maritime places Ptolemais is its neighbor; its breadth is from the village called Xaloth, which lies in the great plain, as far as Bersabe, from which beginning also is taken the breadth of the Upper Galilee, as far as the village Baca, which divides the land of the Tyrians from it; its length is also from Meloth to Thella, a village near to Jordan.[5]

Most of Galilee consists of rocky terrain, at heights of between 500 and 700 m. Several high mountains are in the region, including Mount Tabor and Mount Meron, which have relatively low temperatures and high rainfall. As a result of this climate, flora and fauna thrive in the region. At the same time, many birds annually migrate from colder climates to Africa and back through the Hula–Jordan corridor. The streams and waterfalls, the latter mainly in Upper Galilee, along with vast fields of greenery and colourful wildflowers, as well as numerous towns of biblical importance, make the region a popular tourist destination.

Due to its high rainfall 900–1,200 millimetres (35–47 in), mild temperatures and high mountains (Mount Meron's elevation is 1,000–1,208 m), the upper Galilee region contains some distinctive flora and fauna: prickly juniper (Juniperus oxycedrus), Lebanese cedar (Cedrus libani), which grows in a small grove on Mount Meron, cyclamens, paeonias, and Rhododendron ponticum which sometimes appears on Meron.

Western Galilee (Hebrew: גליל מערבי, romanized: Galil Ma'aravi) is a modern term referring to the western part of the Upper Galilee and its shore, and usually also the northwestern part of the Lower Galilee, mostly overlapping with Acre sub-district. Galilee Panhandle is a common term referring to the "panhandle" in the east that extends to the north, where Lebanon is to the west, and includes Hula Valley and Ramot Naftali mountains of the Upper Galilee.

History

Iron Age and Hebrew Bible

According to the Bible, Galilee was named by the Israelites and was the tribal region of Naphthali and Dan, at times overlapping the Tribe of Asher's land.[6] Normally,[when?] Galilee is just referred to as "Naphthali".

1 Kings 9 states that Solomon rewarded his Phoenician ally, King Hiram I of Sidon, with twenty cities in the land of Galilee, which would then have been either settled by foreigners during and after the reign of Hiram or by those who had been forcibly deported there by later conquerors such as the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Hiram, to reciprocate previous gifts given to David, accepted the upland plain among the Naftali Mountains and renamed it "the land of Cabul" for a time.[7]

In the Iron Age II, Galilee was part of the Kingdom of Israel, which fell to the Assyrians. Archaeological survey conducted by Zvi Gal in Lower Galilee indicates that the area became deserted following the Assyrian conquest in the 8th century and remained so for several centuries; the local Israelite population was carried off to Assyria after 732 BCE.[8][9] Yardenna Alexandre discovered minor short-lived Israelite settlements in the Naḥal Ẓippori basin, which were built by survivors of the Assyrian conquest. Elsewhere, Galilee was depopulated.[10] But there is evidence of Assyrian presence, based on artefacts in Cana,[11] and Konrad Schmid and Jens Schroter believe it was likely that Assyrians settled in the region.[12]

Hellenistic period

Up until the end of the Hellenistic period and before the Hasmonean conquest, the Galilee was sparsely populated, with the majority of its inhabitants concentrated in large fortified centers on the edges of the western and central valleys. Based on archeological evidence from Tel Anafa, Kedesh, and ash-Shuhara, the Upper Galilee was then home to a pagan population with close ties to the Phoenician coast.[13]

Hasmonean period

During the expansion of the Hasmonean kingdom of Judea, much of the Galilee region was conquered and annexed by the first Hasmonean king Aristobulus I (104–103 BCE). Following the Hasmonean conquest, there was a significant Jewish influx into the area. Sites including Yodfat, Meiron, Sepphoris, Shikhin, Qana, Bersabe, Zalmon, Mimlah, Migdal, Arbel, Kefar Hittaya, and Beth Ma'on have archeological-chronological evidence for this settlement wave.[13]

Josephus, who based his account on Timagenes of Alexandria, claimed that Aristobulus I had forcibly converted the Itureans to Judaism while annexing a portion of their territory. Schürer believed this information to be accurate and came to the conclusion that the "Jewish" Galilee of Jesus' day was actually inhabited by the offspring of those same Iturean converts. Other scholars have suggested that the Itureans underwent a voluntary conversion to Judaism in the Upper Galilee, or at the very least in the Eastern Upper Galilee. However, archeological information does not support either proposal, as Iturean material culture has been identified clearly in the northern Golan Heights and Mount Hermon, and not in the Galilee, and it is clear that this area remained outside Hasmonean borders.[13]

Roman period

In the early Roman period, Galilee was predominantly Jewish. Archaeological evidence from multiple sites reveals Jewish customs, including the use of limestone vessels, ritual baths for purity, and secondary burial practices.[14] A significant wave of Jewish settlement arrived in the region following the Roman conquest of 63 BCE.[13] Large towns such as Kefar Hananya, Parod, Ravid, Mashkaneh, Sabban, and Tiberias were established by the end of the first century BCE or the start of the first century CE.[13] By the end of the first century CE, the Galilee was dotted with small towns and villages. While Josephus writes there were 204 small towns, modern scholars consider this an exaggeration.

Galilee's economy under Roman rule thrived on a combination of agriculture, fishing, and specialized crafts. Excavations in villages like Nazareth have revealed extensive agricultural infrastructure, including numerous olive presses and granaries.[14] Olive was extensively grown in parts of Upper Galilee.[15] Many towns and villages, particularly those around the Sea of Galilee benefited from both fertile land and a thriving fishing industry.[14] In Tarichaea (Magdala), salted, dried, and pickled fish were significant export goods.[14][15] Galilee also had specialized production centers.[14] Shihin, near Sepphoris, produced most of the region's storage jars. Kefar Hananya in Upper Galilee manufactured various tableware forms, supplying markets across Galilee, the Golan Heights, the Decapolis, coastal areas, and the Beth Shean Valley.[14]

Josephus describes the Jewish population of Galilee as being nationalist and hostile to Jewish city-dwellers, making them the first target for the Romans during the Jewish-Roman wars. Bargil Pixner believes they descended from a Davidic Jewish clan from Babylon.[11] But according to archaeological and literary evidence, upper and lower Galilee were 'very much in constant touch with the gentile, Greek-speaking cities that surrounded them.' Many Galileans were bilingual and made daily contacts with Jerusalem and gentiles around the Roman territory.[16]

Markus Cromhout states that while Galileans, Judeans and diasporic Judeans were all Jewish, the Galileans had their unique social, political and economic matrix. In terms of ethnicity, Galileans were ethnic Judeans, which generally saw themselves also as Israelites, but could be also identified with localized characteristics, such as Sepphorean.[17] Others argue that Galileans and Judeans were distinct people groups. Outsiders generally conflated them due to Hellenistic-Roman culture, which grouped all diverse groups in Palestine and their related diasporas as "Judean".[18]

In 4 BCE, a rebel named Judah plundered Galilee's largest city, Sepphoris. According to Josephus, the Syrian governor Publius Quinctilius Varus responded by sacking Sepphoris and selling the population into slavery, but the region's archaeology lacks evidence of such destruction.[20][21] After the death of Herod the Great that same year, his son Herod Antipas was appointed as tetrarch of Galilee by the Roman emperor Augustus. Galilee remained a Roman client state and Antipas paid tribute to the Roman Empire in exchange for Roman protection.[19]

The Romans did not station troops in Galilee, but threatened to retaliate against anyone who attacked it. As long as he continued to pay tribute, Antipas was permitted to govern however he wished[19] and was permitted to mint his own coinage. Antipas was relatively observant of Jewish laws and customs. Although his palace was decorated with animal carvings, which many Jews regarded as a transgression against the law prohibiting idols, his coins bore only agricultural designs, which his subjects deemed acceptable.[citation needed]

In general, Antipas was a capable ruler. Josephus does not record any instance of his use of force to put down an uprising and he had a long, prosperous reign. However, many Jews probably resented him as not sufficiently devout.[19] Antipas rebuilt the city of Sepphoris,[21] and in either 18 CE or 19 CE, he founded the new city of Tiberias. These two cities became Galilee's largest cultural centers.[19] They were the main centers of Greco-Roman influence, but were still predominantly Jewish. A massive gap existed between the rich and poor,[21] but lack of uprisings suggest that taxes were not exorbitantly high and that most Galileans did not feel their livelihoods were being threatened.[19]

Late in his reign, Antipas married his half-niece Herodias, who was already married to one of her other uncles. His wife, whom he divorced, fled to her father Aretas, an Arab king, who invaded Galilee and defeated Antipas's troops before withdrawing. Both Josephus and the Gospel of Mark[22] record that the itinerant preacher John the Baptist criticized Antipas over his marriage, and Antipas consequently had him imprisoned and then beheaded.[19] In around 39 CE, at the urging of Herodias, Antipas went to Rome to request that he be elevated from the status of tetrarch to the status of king. The Romans found him guilty of storing arms, so he was removed from power and exiled, ending his forty-three-year reign. During the Great Revolt (66–73 CE), a Jewish mob destroyed Herod Antipas's palace.[19]

Overall, Galilee under Antipas's rule was marked by significant demographic instability. Diseases like malaria were rampant, internal migration between urban and rural areas were frequent and women generally gave birth at young ages while married to older men. Birth control, including infanticide, was not practiced. Many young men, especially marginal villagers, migrated to urban areas to find wives or alternatively, employment. Finding wives was presumed to be competitive since widows often refused to marry past the age of 30 compared to widowers. According to Jonathan L. Reed, this can provide insight on the tropes of New Testament literature, such as miraculous healings and the itinerant lifestyle of Jesus and his disciples.[23]

In 66 CE, during the Great Jewish Revolt, Josephus was appointed by the Jerusalem provisional government to command Galilee. The region experienced internal conflicts among cities such as Sepphoris and Tiberias, with factions opposing Josephus's authority and warring for control. Sepphoris and other strong cities attempted to remain neutral by maintaining alliances with Rome. Despite opposition, Josephus managed to secure internal peace and fortified nineteen cities in preparation for the Roman invasion; nearly half of them were uncovered by archaeologists. In 67 CE, the Roman army, led by general Vespasian, arrived in Acre. Josephus's account, The Jewish War, details the Roman campaign in Galilee, starting with the siege and capture of Gabara, followed by Jotapata (where Josephus was captured), and continuing with Tiberias, Taricheae, Gamala, Tabor, and ending in Gischala. While not all of Galilee was devastated, the conquered cities were razed, and many inhabitants were sold into slavery.[9]

Late Roman period

Judaism reached its political and cultural zenith in the Galilee during the late second and early third century CE. According to rabbinic sources, Judah ha-Nasi's political leadership was at its strongest in relation to the Jewish community in Syria Palaestina, the Diaspora, and the Roman Authorities during this time. Judah's redaction of the Mishnah at this time period represented the peak of intense cultural activity. Archaeological surveys in the Galilee have revealed that the region experienced its height of thriving settlement during this time.[13]

According to medieval Hebrew legend, Shimon bar Yochai, one of the most famed of all the tannaim, wrote the Zohar while living in Galilee.[24]

Byzantine period

After the completion of the Mishnah, which marked the conclusion of the tannaitic era, came the period of the amoraim. The Jerusalem Talmud, the principal work of the amoraim in Palestine, is primarily discussions and interpretations of the Mishnah, and according to academic research, most of it was edited in Tiberias. The vast majority of the amoraim named there, as well as the majority of the settlements or place names referenced, were Galileans.[13] By the middle of the fourth century, the Jerusalem Talmud's compilation and editing processes abruptly came to a halt, as Talmudic scholar Yaacov Sussmann put it: "The development of the Jerusalem Talmud seems to have abruptly ceased, as if severed by a sharp and sudden blade".[25][13]

Demographically, during the fourth century the entire region witnessed a significant population decrease, resulting in the abandonment of several notable settlements.[13] In approximately 320 CE, Christian bishop Epiphanius reported that all the major cities and villages in Galilee were entirely Jewish.[26] During the Byzantine period, however, Galilee's Jewish population experienced a decline, while Christian settlement grew. Archaeological data indicates that in the third and fourth centuries, several Jewish sites were abandoned, and some Christian villages were established on or near these deserted locations. Certain settlements, such as Rama, Magdala, Kafr Kanna, Daburiyya, and Iksal, which were materially Jewish during the Roman period, were now predominantly inhabited by Christians or had a significant Christian population. Safrai and Liebner argue that the decline of the Jewish population and the expansion of the Christian population in the region were separate events that happened at different times. Throughout this period, religious segregation between Christian and Jewish villages endured, with few exceptions like Capernaum and perhaps Nazareth, due to their sanctity in Christian tradition.[13]

Leibner has proposed tying the end of the Palestinian Amoraic period, the impact of historical occurrences like the Christianization of the Roman Empire and of Palestine, the apparent cessation of activities of at least some of the batei midrash and the transformation of the Galilee from a densely populated Jewish area to a collection of communities surrounded by non-Jewish areas to this demographic crisis. He assumed that Christian population in Galilee was not composed of Jews who converted to Christianity. This is supported by the fact that trustworthy historical records, which mention Jewish conversion to Christianity in Byzantine Palestine, refer to individual cases rather than entire villages, unlike the records from the western part of the empire.[13]

Eastern Galilee retained a Jewish majority until at least the seventh century.[27] Over time, this area experienced a decline in population due to raids by nomadic groups and insufficient protection from the central government.[28]

Early Muslim and Crusader periods

After the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 630s, the Galilee formed part of Jund al-Urdunn (the military district of Jordan), itself part of Bilad al-Sham (Islamic Syria). Its major towns were Tiberias the capital of the district, Qadas, Beisan, Acre, Saffuriya, and Kabul.[29] During the early Islamic period, Galilee underwent a process of Arabization and Islamization, similar to other areas in the region. Under Umayyad rule, Islamic rule was gradually consolidated in newly conquered territories, and some Muslims settled in the villages, establishing residency there.[30] Later, under Abbasid rule, geographer al-Ya'qubi (d. 891), who referred to the region as 'Jabal al-Jalil', noted that its inhabitants were Arabs from the Amila tribe.[31]

The Islamization process in which began with the settlement of nomadic tribes. Michael Ehrlich suggests that during the Early Islamic period, the majority of people in the Western Galilee and Lower Galilee likely converted to Islam, while in the Eastern Galilee, the Islamization process continued for a more extended period, lasting until the Mamluk period.[32] According to Moshe Gil, Jews in rural Galilean areas frequently succeeded in upholding community life during and for decades after the Umayyad period. He comes to the conclusion that several Galilean Jewish communities "retained their ancient character".[30]

The Shia Fatimids conquered the region in the 10th century; a breakaway sect, venerating the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim, formed the Druze religion, centered in Mount Lebanon and partially in the Galilee. During the Crusades, Galilee was organized into the Principality of Galilee, one of the most important Crusader seigneuries.[citation needed] According to Moshe Gil, during the periods of Fatimid and Crusader rule, the rural Jewish population of Galilee experienced a gradual decline and flight. He supports his argument by referring to 11th-century Cairo Geniza documents related to transactions in Ramla and other areas in central Palestine, where Jews claimed to have ancestral ties to places like Gush Halav, Dalton, or 'Amuqa, suggesting that Jewish flight from Galilee occurred during that time.[30]

Ayyubid and Mamluk periods

Sunni Muslims began to immigrate to Safed and its surroundings starting in the Ayyubid period, and in particular during the Mamluk period. These immigrants included Sufi preachers who were crucial in converting the locals to Islam in Safed's rural area. Jewish immigrants did, however, come to the area in waves, during the period of the destruction of Tyre and Acre in 1291 and particularly after the Jewish expulsion from Spain in 1492. These immigrants, who included scholars and other urban elites, turned the Jewish community from a rural community into an urban hub which exerted its influence well beyond the regional boundaries of Upper Galilee.[32]

Ottoman era

During Early Ottoman era, the Galilee was governed as the Safad Sanjak, initially part of the larger administrative unit of Damascus Eyalet (1549–1660) and later as part of Sidon Eyalet (1660–1864). During the 18th century, the administrative division of Galilee was renamed to Acre Sanjak, and the Eyalet itself became centered in Acre, factually becoming the Acre Eyalet between 1775 and 1841.

The Jewish population of Galilee increased significantly following their expulsion from Spain and welcome from the Ottoman Empire. The community for a time made Safed an international center of cloth weaving and manufacturing, as well as a key site for Jewish learning.[33] Today it remains one of Judaism's four holy cities and a center for kabbalah.

In the mid-17th century Galilee and Mount Lebanon became the scene of the Druze power struggle, which came in parallel with much destruction in the region and decline of major cities.

In the mid-18th century, Galilee was caught up in a struggle between the Arab leader Zahir al-Umar and the Ottoman authorities who were centred in Damascus. Zahir ruled Galilee for 25 years until Ottoman loyalist Jezzar Pasha conquered the region in 1775.

In 1831, the Galilee, a part of Ottoman Syria, switched hands from Ottomans to Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt until 1840. During this period, aggressive social and politic policies were introduced, which led to a violent 1834 Arab revolt. In the process of this revolt the Jewish community of Safed was greatly reduced, in the event of Safed Plunder by the rebels. The Arab rebels were subsequently defeated by the Egyptian troops, though in 1838, the Druze of Galilee led another uprising. In 1834 and 1837, major earthquakes leveled most of the towns, resulting in great loss of life.

Following the 1864 Tanszimat reforms in the Ottoman Empire, the Galilee remained within Acre Sanjak, but was transferred from Sidon Eyalet to the newly formed Syria Vilayet and shortly, from 1888, became administered from Beirut Vilayet.

In 1866, Galilee's first hospital, the Nazareth Hospital, was founded under the leadership of American-Armenian missionary Dr. Kaloost Vartan, assisted by German missionary John Zeller.

In the early 20th century, Galilee remained part of Acre Sanjak of Ottoman Syria. It was administered as the southernmost territory of the Beirut Vilayet.

British administration

Following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, and the Armistice of Mudros, it came under British rule, as part of the Occupied Enemy Territory Administration. Shortly after, in 1920, the region was included in the British Mandate territory, officially a part of Mandatory Palestine from 1923.

Modern Israeli period

After the 1948 Arab–Israeli war, nearly the whole of Galilee came under Israel's control. A large portion of the population fled or was forced to leave, leaving dozens of entire villages empty; however, a large Israeli Arab community remained based in and near the cities of Nazareth, Acre, Tamra, Sakhnin, and Shefa-'Amr, due to some extent to a successful rapprochement with the Druze. The kibbutzim around the Sea of Galilee were sometimes shelled by the Syrian army's artillery until Israel seized Western Golan Heights in the 1967 Six-Day War.

During the 1970s and the early 1980s, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) launched multiple attacks on towns and villages of the Upper and Western Galilee from Lebanon. This came in parallel to the general destabilization of Southern Lebanon, which became a scene of fierce sectarian fighting which deteriorated into the Lebanese Civil War. On the course of the war, Israel initiated Operation Litani (1979) and Operation Peace For Galilee (1982) with the stated objectives of destroying the PLO infrastructure in Lebanon, protecting the citizens of the Galilee and supporting allied Christian Lebanese militias. Israel took over much of southern Lebanon in support of Christian Lebanese militias until 1985, when it withdrew to a narrow security buffer zone.

From 1985 to 2000, Hezbollah, and earlier Amal, engaged the South Lebanon Army supported by the Israel Defense Forces, sometimes shelling Upper Galilee communities with Katyusha rockets. In May 2000, Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak unilaterally withdrew IDF troops from southern Lebanon, maintaining a security force on the Israeli side of the international border recognized by the United Nations. The move brought a collapse to the South Lebanon Army and takeover of Southern Lebanon by Hezbollah. However, despite Israeli withdrawal, clashes between Hezbollah and Israel continued along the border, and UN observers condemned both for their attacks.

The 2006 Israel-Lebanon conflict was characterized by round-the-clock Katyusha rocket attacks (with a greatly extended range) by Hezbollah on the whole of Galilee, with long-range, ground-launched missiles hitting as far south as the Sharon Plain, Jezreel Valley, and Jordan Valley below the Sea of Galilee.

Demography

In 2006, there were 1.2 million residents in Galilee, of whom 47% were Jewish.[34] The Jewish Agency has attempted to increase the Jewish population in this area,[35] but the non-Jewish population also has a high growth rate.[34]

The largest cities in the region are Acre, Nahariya, Nazareth, Safed, Karmiel, Shaghur, Shefa-'Amr, Afula, and Tiberias.[36] The port city of Haifa serves as a commercial center for the whole region.

Because of its hilly terrain, most of the people in the Galilee live in small villages connected by relatively few roads.[37] A railroad runs south from Nahariya along the Mediterranean coast, and a fork to the east was opened in 2016. The main sources of livelihood throughout the area are agriculture and tourism. Industrial parks are being developed, bringing further employment opportunities to the local population which includes many recent immigrants. The Israeli government is contributing funding to the private initiative, the Galilee Finance Facility, organised by the Milken Institute and Koret Economic Development Fund.[38]

The Galilee is home to a large Arab population,[39][40] with a Muslim majority and two smaller populations, of Druze and Arab Christians, of comparable sizes. Both Israeli Druze and Christians have their majorities in the Galilee.[41][42] Other notable minorities are the Bedouin, the Maronites and the Circassians.

The north-central portion of the Galilee is also known as Central Galilee, stretching from the border with Lebanon to the northern edge of the Jezreel Valley. It includes the cities of Nazareth and Sakhnin, has an Arab majority of 75%, with most of the Jewish population living in hilltop cities like Upper Nazareth. The northern half of the central Lower Galilee, surrounding Karmiel and Sakhnin, is known as the "Heart of the Galilee".

The eastern Galilee is nearly 100% Jewish. This part includes the Finger of the Galilee, the Jordan River Valley, and the shores the Sea of Galilee, and contains two of Judaism's Four Holy Cities.

The southern part of the Galilee, including Jezreel Valley, and the Gilboa region are nearly 100% Jewish, with a few small Arab villages near the West Bank border. About 80% of the population of the Western Galilee is Jewish, all the way up to the Lebanese border. Jews form a small majority in the mountainous Upper Galilee, with a significant minority Arab population, mainly Druze and Christians.

As of 2011, the Galilee is attracting significant internal migration of Haredi Jews, who are increasingly moving to the Galilee and Negev as an answer to rising housing prices in central Israel.[43]

Tourism

Galilee is a popular destination for domestic and foreign tourists who enjoy its scenic, recreational, and gastronomic offerings. The Galilee attracts many Christian pilgrims, as many of the miracles of Jesus occurred, according to the New Testament, on the shores of the Sea of Galilee—including his walking on water, calming the storm, and feeding five thousand people in Tabgha. Numerous sites of biblical importance are located in the Galilee, such as Megiddo, Jezreel Valley, Mount Tabor, Hazor, Horns of Hattin, and more.

A popular hiking trail known as the yam leyam, or sea-to-sea, starts hikers at the Mediterranean. They then hike through the Galilee mountains, Tabor, Neria, and Meron, until their final destination, the Kinneret (Sea of Galilee).

In April 2011, Israel unveiled the Jesus Trail, a 40-mile (60-km) hiking trail in the Galilee for Christian pilgrims. The trail includes a network of footpaths, roads, and bicycle paths linking sites central to the lives of Jesus and his disciples, including Tabgha, the traditional site of Jesus's miracle of the loaves and fishes, and the Mount of Beatitudes, where he delivered his Sermon on the Mount. It ends at Capernaum on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, where Jesus espoused his teachings.[44]

Many kibbutzim and moshav families operate Zimmerim, from the Yiddish word for 'room', צימער, from 'Zimmer' in German, with the Hebrew ending for plural, -im; the local term for a Bed and breakfast. Numerous festivals are held throughout the year, especially in the autumn and spring holiday seasons. These include the Acre (Acco) Festival of Alternative Theater,[45] the olive harvest festival, music festivals featuring Anglo-American folk, klezmer, Renaissance, and chamber music, and Karmiel Dance Festival.

Cuisine

The cuisine of the Galilee is very diverse. The meals are lighter than in the central and southern regions. Dairy products are heavily consumed, especially the Safed cheese that originated in the mountains of the Upper Galilee. Herbs like thyme, mint, parsley, basil, and rosemary are very common with everything, including dips, meat, fish, stews and cheese. In the eastern part of the Galilee, there is freshwater fish as much as meat, especially the Tilapia that lives in the Sea of Galilee, Jordan river, and other streams in the region.

Fish is filled with thyme and grilled with rosemary to flavor, or stuffed with oregano leaves, then topped with parsley and served with lemon to squash. This technique exists in other parts of the country including the coasts of the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. A specialty of the region is a baked Tilapia flavored with celery, mint and a lot of lemon juice. Baked fish with tahini is also common in Tiberias. The coastal Galileans prefer to replace the tahini with yogurt and add sumac on top.

The Galilee is famous for its olives, pomegranates, wine and especially its Labneh w'Za'atar which is served with pita bread, meat stews with wine, pomegranates and herbs such as akub, parsley, khalmit, mint, fennel, etc. are common. Galilean kubba is usually flavored with cumin, cinnamon, cardamom, concentrated pomegranate juice, onion, parsley and pine nuts and served as meze with tahini dip.

Kebabs are made almost in the same way, with sumac replacing cardamom and with carob sometimes replacing the pomegranate juice. Because of its climate, beef has become more popular than lamb, although both are still eaten there. Dates are popular in the tropical climate of the Eastern Galilee.

Subregions

The definition of Galilee varies depending on the period, author, and point of view (geological, geographical, administrative). Ancient Galilee consisted in broad terms of the Upper and Lower Galilee. Today the northwestern part of the Upper Galilee is in Southern Lebanon, with the rest being in Israel. The Israeli Galilee is often divided into these subregions, which often overlap:

- Upper Galilee extends from the Beit HaKerem Valley northwards into southern Lebanon. Its eastern border is the Hula Valley and the Sea of Galilee separating it from the Golan Heights. To the west it reaches to the Coastal Plain which separates it from the Mediterranean.

- Lower Galilee covers the area north of the Valleys (Jezreel, Harod and Beth Shean Valley) and south of the Beit HaKerem Valley. Its borders to the east on the Jordan Rift Valley. It contains the Arab city of Nazareth and the village of Cana.

- The "Galilee Panhandle" (Hebrew: אצבע הגליל, Etzba HaGalil, lit. "Finger of Galilee") is a panhandle along the Hulah Valley, squeezed between the Lebanese border and the Golan Heights; it contains the towns of Metulla and Qiryat Shemona, the Dan and part of the Banias rivers.

The following subregions are sometimes regarded, from different points of view, as distinct from the Galilee, for instance the entire Jordan Valley including the Sea of Galilee and its continuation to the south as one geological and geographical unit, and the Jezreel, Harod, and Beit She'an valleys as "the northern valleys".

- The Hula Valley

- The Korazim Plateau

- The Sea of Galilee and its valley

- The Jordan Valley from the southern tip of the Sea of Galilee down to Beit She'an

- The Jezreel Valley, including in its eastern part, the Harod Valley, which stretches between Afula and the Beit She'an Valley

- The Beit She'an Valley at the junction of the Jordan Valley and the extended Jezreel Valley

- Mount Gilboa

- The Western Galilee is a modern Israeli term, which in its minimal definition refers to the coastal plain just west of the Upper Galilee, also known as Plain of Asher or Plain of the Galilee, which stretches from north of Acre to Rosh HaNikra on the Israel-Lebanon border, and in the common broad definition adds the western part of Upper Galilee, and usually the northwestern part of Lower Galilee as well, corresponding more or less to Acre sub-district or the Northern District.

Gallery

See also

References

- ^ "Galilee". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1879), s.v. Galilaea.

- ^ a b Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features, and Historic Sites (2nd, revised ed.). McFarland. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ Jürgen Zangenberg; Harold W. Attridge; Dale B. Martin (2007). Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in Ancient Galilee: A Region in Transition. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-3-16-149044-6.

- ^ Josephus, J. BJ 3.35

- ^ "Map of the Twelve Tribes of Israel | Jewish Virtual Library". jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ^ Rawlinson, George (1889). "Phoenicia under the hegemony of Tyre (B.C. 1252–877)". History of Phoenicia.

- ^ Zvi Gal, Lower Galilee during the Iron Age (American Schools of Oriental Research Dissertation Series 8; Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1992), p. 108

- ^ a b Jensen, M. H. (2014). The Political History in Galilee from the First Century BCE to the end of the Second Century CE. Galilee in the late Second Temple and Mishnaic periods. Volume 1. Life, culture and society, pp. 51–77

- ^ Yardenna Alexandre (2020). "The Settlement History of Nazareth in the Iron Age and Early Roman Period". 'Atiqot. 98. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ a b Skinner, Andrew C. (1996–1997). "A Historical Sketch of Galilee". Brigham Young University Studies. 36 (3): 113–125. JSTOR 43044121.

- ^ Schmid, Konrad; Schroter, Jens (2021). The Making of the Bible: From the First Fragments to Sacred Scripture. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674248380.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Leibner, Uzi (2009). Settlement and History in Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine Galilee: An Archaeological Survey of the Eastern Galilee. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 321–324, 362–371, 396–400, 414–416. hdl:20.500.12657/43969. ISBN 978-3-16-151460-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Chancey, Mark Alan; Porter, Adam Lowry (2001). "The Archaeology of Roman Palestine". Near Eastern Archaeology. 64 (4): 180. doi:10.2307/3210829. ISSN 1094-2076. JSTOR 3210829.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Seth (2006), Katz, Steven T. (ed.), "Political, social, and economic life in the Land of Israel, 66–c. 235", The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 4, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 38–39, doi:10.1017/chol9780521772488.003, ISBN 978-0-521-77248-8, retrieved 2023-03-31

- ^ Charlesworth, Scott D. (2016). "The Use of Greek in Early Roman Galilee: The Inscriptional Evidence Re-examined". Journal for the Study of the New Testament. 38 (3): 356–395. doi:10.1177/0142064X15621650 – via SageJournals.

- ^ Cromhout, Markus (2008). "Were the Galileans "religious Jews" or "ethnic Judeans?"". HTS Theological Studies. 64 (3) – via Scielo.

- ^ Elliott, John (2007). "Jesus the Israelite Was Neither a 'Jew' Nor a 'Christian': On Correcting Misleading Nomenclature". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus. 5 (2): 119–154. doi:10.1177/1476869007079741 – via Academia.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sanders, E. P. (1993). The Historical Figure of Jesus. London, New York, Ringwood, Australia, Toronto, Ontario, and Auckland, New Zealand: Penguin Books. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-0-14-014499-4.

- ^ Eric M. Meyers,'Sepphoris on the Eve of the Great Revolt (67–68 C.E.): Archaeology and Josephus,' in Eric M. Meyers,Galilee Through the Centuries: Confluence of Cultures, Eisenbrauns, 1999 pp.109ff., p. 114: (Josephus, Ant. 17.271–87; War 2.56–69).

- ^ a b c d Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. New York City, New York and London, England: T & T Clark. pp. 164–169. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- ^ Bible, Mark 6:17–29

- ^ Reed, Jonathan L. (2010). "Instability in Jesus' Galilee: A Demographic Perspective". Journal of Biblical Literature. 129 (2): 343–365. doi:10.2307/27821023. JSTOR 27821023.

- ^ Scharfstein, S. (2004). Jewish History and You. Ktav Pub. Inc. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-88125-806-6. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ^ Sussmann 1990: 67–103

- ^ Epiphanius, Panarion 30.11.9–10

- ^ Leibner, Uzi, Settlement and Demography in Late Roman and Byzantine Eastern Galilee

- ^ Tramontana, Felicita (2014). "Chapter V Conversion and change in the distribution of the Christian Population". Passages of Faith: Conversion in Palestinian villages (17th century) (1st ed.). Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 114. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc16s06.10. ISBN 978-3-447-10135-6. JSTOR j.ctvc16s06.

- ^ Le Strange, Guy. (1890) Palestine Under the Moslems pp. 30–32.

- ^ a b c Silver, M. M. (2021). The history of Galilee, 47 BCE to 1260 CE : from Josephus and Jesus to the crusades. Lanham, Maryland. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-7936-4945-4. OCLC 1260170710.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Strange, le, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. p. 77.

- ^ a b Ehrlich, Michael (2022). The Islamization of the Holy Land, 634–1800. Leeds, UK: Arc Humanities Press. pp. 59–75. ISBN 978-1-64189-222-3. OCLC 1302180905.

- ^ "The Jewish Agency for Israel". jafi.org.il. Archived from the original on 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ^ a b Ofer Petersburg (December 12, 2007). "Jewish population in Galilee declining". Ynet. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ "30 settlements planned for Negev and Galilee". 2003-08-08. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ^ "Places To Visit In Israel". govisitisrae. Archived from the original on 2013-07-04. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ^ "Galilee in Jesus' Time Was a Center of Change". Ancient History. Archived from the original on 2013-06-15. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ^ Matthew Krieger (November 19, 2007). "Gov't expected to join financing of huge northern development project". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ^ Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (2013). "Localities and Population, by Group, District, Sub-district and Natural Region" (PDF). Statistical Abstract of Israel (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-09-30. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ^ "In Galilee, Israeli Arabs finding greener grass in Jewish areas". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Nov 3, 2008. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ^ Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (2013). "Sources of Population Growth, by District, Population Group and Religion" (PDF). Statistical Abstract of Israel (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-21. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ^ Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (2002). The Arab Population in Israel (PDF) (Report). Statistilite. Vol. 27. sec. 23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2014-06-15.

- ^ Peteresburg, Ofer (23 February 2011). "Haredim 'taking over'". Ynetnews. Israel Business, ynetnews.com. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ^ Daniel Estrin, Canadian Press (April 15, 2011). "Israel unveils hiking trail in Galilee for Christian pilgrims". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "Acco Festival". accofestival.co.il. Archived from the original on 2015-07-02. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Galilee". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Galilee". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

Further reading

- Aviam, M., "Galilee: The Hellenistic to Byzantine Periods," in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, vol. 2 (4 vols) (Jerusalem: IES / Carta), 1993, 452–58.

- Meyers, Eric M. (ed), Galilee through the Centuries: Confluence of Cultures (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1999) (Duke Judaic Studies 1).

- Chancey, A.M., Myth of a Gentile Galilee: The Population of Galilee and New Testament Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002) (Society of New Testament Monograph Series 118).

- Aviam, M., "First-century Jewish Galilee: An archaeological perspective," in Edwards, D.R. (ed.), Religion and Society in Roman Palestine: Old Questions, New Approaches (New York / London: Routledge, 2004), 7–27.

- Aviam, M., Jews, Pagans and Christians in the Galilee (Rochester NY: University of Rochester Press, 2004) (Land of Galilee 1).

- Chancey, Mark A., Greco-Roman Culture and the Galilee of Jesus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006) (Society for New Testament Studies Monograph Series, 134).

- Freyne, Sean, "Galilee and Judea in the First Century," in Margaret M. Mitchell and Frances M. Young (eds), Cambridge History of Christianity. Vol. 1. Origins to Constantine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006) (Cambridge History of Christianity), 163–94.

- Zangenberg, Jürgen, Harold W. Attridge and Dale B. Martin (eds), Religion, Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Galilee: A Region in Transition (Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck, 2007) (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, 210).

- Fiensy, David A., "Population, Architecture, and Economy in Lower Galilean Villages and Towns in the First Century AD: A Brief Survey," in John D. Wineland, Mark Ziese, James Riley Estep Jr. (eds), My Father's World: Celebrating the Life of Reuben G. Bullard (Eugene (OR), Wipf & Stock, 2011), 101–19.

- Safrai, Shmuel, "The Jewish Cultural Nature of Galilee in the First Century" The New Testament and Christian–Jewish Dialogue: Studies in Honor of David Flusser, Immanuel 24/25 (1990): 147–86; electronically published on jerusalemperspective.com.

External links

- Galilee (definition of) on Haaretz.com