Jack Katz (artist)

| Jack Katz | |

|---|---|

Katz in 2018 | |

| Born | September 27, 1927 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Area(s) | artist, writer |

| Pseudonym(s) | Jay Hawk, Vaughn Beering, Alac Justice, Alec Justice, David Hadley |

Notable works | The First Kingdom |

| Awards | Inkpot Award, 1982 |

Jack Katz (born September 27, 1927)[1][2] is an American comic book artist and writer, painter and art teacher known for his graphic novel The First Kingdom, a 24-issue epic he began during the era of underground comix.

Influenced by such illustrative comic-strip artists as Hal Foster and Alex Raymond, Katz attended the School of Industrial Art in New York City. He began working for comic-book publishers in the 1940s, during the period fans and historians call the Golden Age of Comic Books. Though continuing to work in comics through the 1950s, his slow pace and highly detailed, idiosyncratic art style prompted him to leave that field for 14 years. Circa 1969, he returned to mainstream color comics as well as to black-and-white horror-comics magazines, and after a move to California embarked upon The First Kingdom, a serialized work that later became considered a precursor to, or an early form of, the graphic novel. He completed it in 1986, and went on to write and draw further works in that vein, and to teach art.

Early life and career

[edit]Katz was born in Brooklyn, New York, and moved to Canada a few days after he was born. He returned to the United States when he was around eight years old.[3][4] While attending the School of Industrial Art in New York City, he established bonds of friendship with future comic artists Alex Toth, Alfonso Greene and Pete Morisi.

Katz's work in mainstream comics spans both the Golden and Silver Ages, and was done under a variety of pseudonyms such as Jay Hawk,[5] Vaughn Beering, Alac Justice, Alec Justice, and David Hadley.[6][7][8] He got his start in the industry in 1943, working in the C. C. Beck and Pete Costanza studio[6] on that duo's feature Bulletman.[9] In 1944[9] or 1945,[6] working as a letterer in the comics studio of Jerry Iger, he became acquainted with artist Matt Baker, whom he considered "one of the top illustrators, and a good storyteller".[9]

From 1946 to 1951, he worked as an art assistant on various King Features Syndicate comic strips.[6] Katz worked on Thimble Theatre as an assistant artist, working with Bela Zaboly and Louis Trakis. Katz worked briefly on Terry and the Pirates as an assistant to George Wunder. As a "detail man", he came into contact with Hal Foster and Alex Raymond, two of the artists who inspired him most in his early years. Katz has considered Foster his "guiding light" since the age of six and believes Foster laid the foundations for the graphic novel. Raymond praised Katz's illustrative style and said that working in comics was a waste of his time. Stanley Kaye, on the other hand, told Katz to persevere.[10]

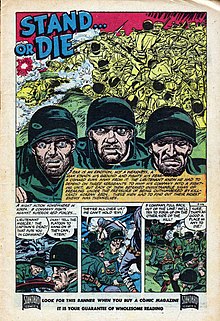

Katz went to work for Standard Comics and its imprints in 1951, doing horror comics, war comics and some romance comics until the company went out of business. From this period comes some of the earliest work that can be identified as his, such as Adventures into Darkness #10 (June 1953).[11] From 1952 to 1956, Katz worked as a penciler and inker at the studio of Jack Kirby and Joe Simon,[6] working alongside Mort Meskin and Marvin Stein. Kirby taught Katz how to ink and use lighting to emphasize dramatic scenes.[12] A slow worker due to heavy detailing (influenced by the style of illustrator Dean Cornwell), Katz was let go and moved on to Timely Comics under Stan Lee around 1954.[13][14] Katz worked on war and horror comics, as well as Westerns, but his pacing continued to cause friction. Without Lee's knowledge, Katz worked on the side for Fiction House, which slowed him down even more.[15] In 1955 he left mainstream comics to paint and teach art, both privately and for the YMCA in New York City.[15] His hiatus from the industry lasted 14 years.

Impressed by Jim Steranko's Captain America, Katz entered mainstream comics for a second time in 1969 and bounced around from job to job.[16] He first found work with Stan Lee at Marvel Comics and worked on books such as Sub-Mariner, Monsters on the Prowl and Adventure into Fear. Katz then worked on House of Secrets and romance comics for DC before moving on to write and illustrate stories for Jim Warren.[17]

In the early 1970s, Katz drew numerous romance comics for DC and Marvel Comics.

Katz got a job with Skywald Publications around 1970, where he believed that he would be able to write his own stories. While there he worked on "Zangar" (from the Jungle Adventures comic book) and is credited with the full art and script for "The Plastic Plague" in the horror-comics magazine Nightmare #14 (Aug. 1973).[18] While remaining with Skywald as an associate editor, Katz moved to California in the early 1970s. It was there he began writing The First Kingdom, integrating into the story ideas that he'd had since his time with Warren Publications.[19]

In 1978, Katz teamed up with his friend Thomas Scortia to create a short-lived comic strip, Galactic Prime. The strip was launched on July 5, 1978, and ran for only seven weeks in his local newspaper, the North East Bay Independent and Gazette.

The First Kingdom

[edit]Moving to California led to Katz's introduction to underground comics. Through independent publishing he saw the potential to create his own story without editorial interference.[4][20] The First Kingdom is a 24-issue, 768-page graphic novel that took Katz 12 years to complete, outside of writing the story. He finished two books per year, intentionally totaling 24 in order to mirror the number of books in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey.[21] Each issue is dedicated to his then-wife, Carolyn.

The epic was published by Comics & Comix Co. from 1974 to 1977, at which point publication was taken over by Bud Plant (a Comics & Comix co-founder) and completed in 1986. Early praise for Kingdom came from Playboy magazine and the Rocket's Blast Comicollector fanzine,[22] but it was never a commercial success due in part to the frequency with which it came out and its adult content.[23] Another contributing factor may have been that Kingdom was sold strictly through mail-order, specialty comic stores and head shops.[citation needed]

Its genre is science fiction-fantasy with a heavier emphasis on science fiction after issue #6.[24] The story opens on a new, post-nuclear era with tribes fighting for survival on a primitive, fantastic Earth filled with gods and monsters. Gods meddle in human affairs, their appearance, temperament and vices resembling the gods of Ancient Greece. The story spans generations and has a huge cast of characters. It abounds with theories to account for religion, evolution, migration and why humans allow themselves to be distracted from the, "plaguing questions of our existence". The story's protagonist, Tundran, is introduced in Book Four. He overcomes obstacles in order to return to his father's usurped kingdom of Moorengan as a liberator. Along the way he falls in love with Fara, a "transgoddess" incarnate, and their adventures together represent the most linear plot line in the story.

The First Kingdom is the first part of a trilogy, which Katz said will include Space Explorers Club and Destiny. He said the first 20 issues are the introduction to the real Kingdom story in issues #21–24.[8] The first 20 issues are filled with histories that are interwoven and repeat the same doomed cycle: a hard-won ascent from primitivity blossoms into a golden age of scientific advancement which inevitably devolves into war and a preoccupation with survival and superstition. Katz's fears concerning the human condition are revealed here.[citation needed] His characters are unable to transcend their "early programming" born out of environmental stresses and cannot escape such base motivations as greed, envy, and jealousy.[citation needed] The chance for humanity to break this cycle comes with the arrival of Queltar in #20, who encourages a select few to join him and embrace their true potential among the stars.

A number of stylistic touches set Katz's illustrative style in Kingdom apart from that of other comic artists. It is highly detailed' all of his human (and humanoid) forms have ideal, heroic bodies rendered with anatomical accuracy; and there are no gutters, with murals filling single-panel pages throughout the work. The quality of Katz's art matures as he progresses further into the story: the panels get larger and he shifts from pen to brush in the fifth book, a suggestion from Jim Steranko.[24]

Will Eisner and Jerry Siegel[25] among many others considered Kingdom to be innovative in many respects. In the foreword to issue #23, Eisner claims the work helped carve a niche for the graphic-novel medium. Comics historian R. C. Harvey believes Katz was the "...first person in comics to pursue a personal vision at such length'".[26] Katz's stated intention in the first issue was to trailblaze: "The work I am undertaking...is the first in a series of books in which I hope to extend the dimension of comics to the potential art form that one of its earliest and greatest artists, Hal Foster, laid down the foundations for."[27]

Attempts have been made to reissue Kingdom as collected volumes. Wallaby Pocket Books published a large-format version of the first six books in 1978.[citation needed] In 2005, Century Comics (under its former name, Mecca Comics Group) released the first volume of an anticipated four-volume set, collecting issues #1–6. The second volume collected issues #7–12 and followed months later, but Century Comics went out of business before it could publish the final two volumes.[citation needed] In May 2013, Titan Comics announced plans to reprint the series in six volumes, remastered from the original art and relettered.[citation needed]

Painting

[edit]In 1956, Katz left the comic book industry and began painting and teaching art in Brooklyn. In September 1962, his work was featured in a one-man show at the Panoras Gallery in Manhattan at 62 West 56th Street. Katz continued to paint through the early 1960s, though there are no records of many of these works.

Katz's painting style, like his comic art style, focuses on human subjects and anatomy. "The figures in the paintings...embrace, entwine, writhe, contort, and suckle. The work blends the realistic with the exaggerated. It is a 1930s, 1940s world, its view unimpeded by fifty years of art trends and theory. The Ashcan School comes to mind."[28]

In 1988, Katz returned to oil painting and completed many works from 1988 – 2003. During this time, Katz also was teaching art in Northern California. After 2003, Katz stopped painting and returned to drawing and developing comic book stories.

Later life and career

[edit]

Since the Kingdom years, Katz has focused on teaching art at a community college in Albany, California, painting and working on graphic novels. Students of his have helped publish a number of books of his works. These include an anatomy book for students (Anatomy by Jack Katz, Volume One) and two books of his sketches (Jack Katz Sketches, Vol. 1 and Jack Katz Sketches, Vol. 2). In 2009, Graphic Novel Literature published Katz's second graphic novel, Legacy. Charlie Novinskie, former president of Century Comics, helped script Legacy.

In 2014, Katz began work on Beyond the Beyond, a 500-page graphic novel, which was a continuation of his themes developed in The First Kingdom series. The book was finished in 2019, but remains unpublished.

In 2019, Katz began a new graphic novel, which he says will be 330 pages long. This new novel is a sequel to Beyond the Beyond.

In October 2020, Katz had a solo exhibition in Berkeley, California titled "The Golden Age and Beyond". The exhibit featured art from his entire career including comic art and paintings.

In September 2021, Liam Sharp's Sharpy Publishing released The Unseen Jack Katz, a collection of unpublished works from the 1970s and 1980s. Funded as a Kickstarter project, the book contained various unfinished stories & comic strips by Katz.

Awards

[edit]Katz was one of the recipients of the Inkpot Award in 1982 at San Diego Comic-Con.[6] In 2023 Jack Katz received the Will Eisner Hall of Fame Award at San Diego Comic-Con. He was not present, but professor Andrew Kunka accepted the award on his behalf and a short acceptance speech was shown on video. [29]

Selected bibliography

[edit]Comics

[edit]Source for Katz's work in mainstream comics:[30]

Archie Comic Publications, Inc.

[edit]- Archie (pencils, inks, 1943)

Fawcett Comics

[edit]- Bulletman (full art, 1943)

Hillman Periodicals

[edit]- Western Fighters (full art, 1949)

Quality Comics

[edit]- Doll Man (inks, c. 1950)

Better/Standard/Pines/Nedor Publications

[edit]- Adventure into Darkness (pencils, 1952–53)

- Exciting War (pencils, 1952)

- Lost Worlds (pencils, 1952)

- New Romances (pencils, 1952)

- Out of the Shadows (pencils, 1952)

- The Unseen (pencils, inks, 1952–53)

Feature Comics

[edit]- Black Magic (full art, 1952)

Marvel Comics (and related imprints)

[edit]- Annie Oakley (full art, c. 1955)

- Arrowhead (full art, 1954)

- Astonishing (full art, mid-1950s)

- Battle Action (full art, mid-1950s)

- Battle (full art, 1955)

- Battlefront (full art, 1954–55)

- Battleground (full art, 1954–55)

- Fear (pencils, 1972)

- Journey into Mystery (full art, 1955)

- Journey into Unknown Worlds (full art, 1955)

- Jungle Tales (full art, mid-1950s)

- Marines in Battle (full art, 1954)

- Marvel Tales (full art, 1954)

- Menace (full art, 1954)

- Monsters on the Prowl (pencils, 1971)

- My Love (full art, c. 1971)

- Mystery Tales (full art, 1955)

- Mystic (full art, 1954)

- Strange Tales (full art, 1954–55)

- Sub-Mariner (pencils, 1969)

- Uncanny Tales (full art, 1954–55)

- Unknown Jungle (full art, 1954)

- War Comics (full art, 1955)

- Western Kid (full art, mid-1950s)

- Wild Western (full art, mid-1950s)

Skywald Publishing Company

[edit]- Nightmare (pencils, 1970–1973)

- Psycho (pencils, 1971–1974)

- Tender Love Stories (pencils, 1971)

- Zangar (pencils, 1971)

DC Comics (and related companies)

[edit]- Falling in Love (pencils, 1972)

- Heart Throbs (full art, c. 1972)

- House of Secrets (pencils, 1972)

- Love Stories (pencils, 1972–73)

- Young Love (pencils, 1971)

- Young Romance (writer, full art, 1972)

Warren Publications

[edit]- Creepy (writer, full art, 1972)

Comics & Comix Co./Bud Plant, Inc.

[edit]- The First Kingdom (writer, artist, 1974–1986)

Wallaby Pocket Books

[edit]- The First Kingdom (includes #1–6, 191 pages, 1978, ISBN 0-671-79016-1)

Mecca Comics Group/Century Comics

[edit]- The First Kingdom, Book 1 (includes #1–6, 198 pages, 2005, ISBN 0-9766651-0-7)

- The First Kingdom, Book 2 (includes #7–12, 2006, ASIN 097666514X)

Graphic Novel Literature

[edit]- Legacy (2009, ISBN 0-9766651-9-0)

Titan Comics

[edit]- The First Kingdom, Book 1 (includes #1–6, 208 pages, 2013, ISBN 978-1782760108)

- The First Kingdom, Book 2 (includes #7–12, 208 pages, 2013, ISBN 978-1782760115)

- The First Kingdom, Book 3 (includes #13–18, 208 pages, 2014, ISBN 978-1782760122)

- The First Kingdom, Book 4 (includes #19–24, 208 pages, 2014, ISBN 978-1782760139)

- The First Kingdom, Book 5 (160 pages, 2014, ISBN 978-1782760146)

- The First Kingdom, Book 6 (112 pages, 2014, ISBN 978-1782760146)

Other works

[edit]- Jack Katz Sketches, Volume 1

- Jack Katz Sketches, Volume 2 (2004)

Windcast Publications

[edit]- Anatomy by Jack Katz, Volume One (2nd ed., 152 pages, 2008, ISBN 0-9772926-1-4)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Miller, John Jackson (June 10, 2005). "Comics Industry Birthdays". Comics Buyer's Guide. Archived from the original on February 18, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ Jack Katz at the Lambiek Comiclopedia

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 3

- ^ a b Zimmerman (1982), p. 38

- ^ Evanier, Mark (April 14, 2008). "Why did some artists working for Marvel in the sixties use phony names?". P.O.V. Online (column). Archived from the original on November 26, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f "Inkpot Award". 27 July 2023.

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 4

- ^ a b Zimmerman (1982), p. 54

- ^ a b c Amash (2010), p. 5

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 17

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 21

- ^ Amash (2010), pp. 37–38

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 40

- ^ Zimmerman (1982), p. 37

- ^ a b Amash (2010), p. 46

- ^ Levin (2005), p. 199

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 48

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 50

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 53

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 54

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 56

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 55

- ^ Levin (2005), p. 197

- ^ a b Sherman (1977), p. 55

- ^ Katz (1978), inside cover

- ^ Levin (2005), p. 204

- ^ Katz (1974), inside cover

- ^ Levin (2005), p. 198

- ^ MacNamee, Olly (July 22, 2023). "SDCC 2023: Eisner Winners 2023". Comicon.com. Retrieved July 24, 2024.

- ^ Amash (2010), p. 58

References

[edit]- Amash, Jim (January 2010). "'We Considered [Comics] An Art Form'". Alter Ego. Vol. 3, no. 91. pp. 3–21. Pages 3–5 online.

- Amash, Jim (March 2010). "'I'm Trying To Prod People to Think'". Alter Ego'. Vol. 3, no. 92. pp. 37–58. Pages 37–38 online.

- Katz, Jack (1974). "Introduction to Book One". The First Kingdom. Grass Valley, California: Comics & Comix Co.

- Katz, Jack (1978). "Foreword to Book Nine". The First Kingdom. Grass Valley, California: Bud Plant, Inc.

- Levin, Bob (2005). Outlaws, Rebels, Freethinkers & Pirates. Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books. pp. 193–205. ISBN 1-56097-631-4.

- Sherman, Bill (1977). "The Kingdom and the Power of Jack Katz". The Comics Journal. No. 38. pp. 51–55.

- Zimmerman, Howard (1982). "Jack Katz: An Intimate Chat About First Kingdom". Comics Scene. Vol. 1, no. 3. Starlog Group. pp. 52–55, 65.

- Zimmerman, Howard (1982). "Jack Katz Part II: Dreams, the Early Days and the Kingdom". Comics Scene. Vol. 1, no. 4. Starlog Group. pp. 37–40, 64.

External links

[edit]- 1927 births

- American comics artists

- American comics writers

- People from Brooklyn

- Alternative cartoonists

- Living people

- 20th-century American painters

- American male painters

- 21st-century American painters

- 21st-century American male artists

- Golden Age comics creators

- Painters from New York City

- High School of Art and Design alumni

- Educators from New York City

- Writers from New York City