Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley | |

|---|---|

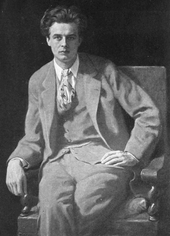

Huxley in 1954 | |

| Born | Aldous Leonard Huxley 26 July 1894 Godalming, Surrey, England |

| Died | 22 November 1963 (aged 69) Los Angeles County, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Compton, Surrey |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | Balliol College |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | Matthew |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Aldous Leonard Huxley (/ˈɔːldəs/ AWL-dəs; 26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher.[1][2][3][4] His bibliography spans nearly 50 books,[5][6] including non-fiction works, as well as essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxley family, he graduated from Balliol College, Oxford, with a degree in English literature. Early in his career, he published short stories and poetry and edited the literary magazine Oxford Poetry, before going on to publish travel writing, satire, and screenplays. He spent the latter part of his life in the United States, living in Los Angeles from 1937 until his death.[7] By the end of his life, Huxley was widely acknowledged as one of the foremost intellectuals of his time.[8] He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature nine times,[9] and was elected Companion of Literature by the Royal Society of Literature in 1962.[10]

Huxley was a pacifist.[11] He grew interested in philosophical mysticism,[11][8][12] as well as universalism,[11][13] addressing these subjects in his works such as The Perennial Philosophy (1945), which illustrates commonalities between Western and Eastern mysticism, and The Doors of Perception (1954), which interprets his own psychedelic experience with mescaline. In his most famous novel Brave New World (1932) and his final novel Island (1962), he presented his visions of dystopia and utopia, respectively.

Early life

[edit]

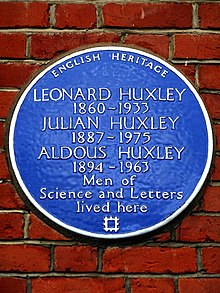

Huxley was born in Godalming, Surrey, England, on 26 July 1894.[14][15] He was the third son of the writer and schoolmaster Leonard Huxley, who edited The Cornhill Magazine,[16] and his first wife, Julia Arnold, who founded Prior's Field School. Julia was the niece of poet and critic Matthew Arnold and the sister of Mrs. Humphry Ward. Julia named him Aldous after a character in one of her sister's novels.[17] Aldous was the grandson of Thomas Henry Huxley, the zoologist, agnostic, and controversialist who had often been called "Darwin's Bulldog". His brother Julian Huxley and half-brother Andrew Huxley also became outstanding biologists. Aldous had another brother, Noel Trevenen Huxley (1889–1914), who took his own life after a period of clinical depression.[18]

As a child, Huxley's nickname was "Ogie", short for "Ogre".[19] He was described by his brother, Julian, as someone who frequently contemplated "the strangeness of things".[19] According to his cousin and contemporary Gervas Huxley, he had an early interest in drawing.[19]

Huxley's education began in his father's well-equipped botanical laboratory, after which he enrolled at Hillside School near Godalming.[20][21] He was taught there by his own mother for several years until she became terminally ill. After Hillside he went on to Eton College. His mother died in 1908, when he was 14 (his father later remarried). He contracted the eye disease keratitis punctata in 1911; this "left [him] practically blind for two to three years"[22] and "ended his early dreams of becoming a doctor".[23] In October 1913, Huxley entered Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied English literature.[24] He volunteered for the British Army in January 1916, for the Great War; however, he was rejected on health grounds, being half-blind in one eye.[24] His eyesight later partly recovered. He edited Oxford Poetry in 1916, and in June of that year graduated BA with first class honours.[24] His brother Julian wrote:

I believe his blindness was a blessing in disguise. For one thing, it put paid to his idea of taking up medicine as a career ... His uniqueness lay in his universalism. He was able to take all knowledge for his province.[25]

Following his years at Balliol, Huxley, being financially indebted to his father, decided to find employment. He taught French for a year at Eton College, where Eric Blair (who was to take the pen name George Orwell) and Steven Runciman were among his pupils. He was mainly remembered as being an incompetent schoolmaster unable to keep order in class. Nevertheless, Blair and others spoke highly of his excellent command of language.[26]

Huxley also worked for a time during the 1920s at Brunner and Mond, an advanced chemical plant in Billingham in County Durham, northeast England. According to an introduction to his science fiction novel Brave New World (1932), the experience he had there of "an ordered universe in a world of planless incoherence" was an important source for the novel.[27]

Career

[edit]

Huxley completed his first (unpublished) novel at the age of 17 and began writing seriously in his early twenties, establishing himself as a successful writer and social satirist. His first published novels were social satires, Crome Yellow (1921), Antic Hay (1923), Those Barren Leaves (1925), and Point Counter Point (1928). Brave New World (1932) was his fifth novel and first dystopian work. In the 1920s, he was also a contributor to Vanity Fair and British Vogue magazines.[28]

Contact with the Bloomsbury Group

[edit]

During the First World War, Huxley spent much of his time at Garsington Manor near Oxford, home of Lady Ottoline Morrell, working as a farm labourer. While at the Manor, he met several Bloomsbury Group figures, including Bertrand Russell, Alfred North Whitehead,[29] and Clive Bell. Later, in Crome Yellow (1921), he caricatured the Garsington lifestyle. Jobs were very scarce, but in 1919, John Middleton Murry was reorganising the Athenaeum and invited Huxley to join the staff. He accepted immediately, and quickly married the Belgian refugee Maria Nys (1899–1955), also at Garsington.[30] They lived with their young son in Italy part of the time during the 1920s, where Huxley would visit his friend D. H. Lawrence. Following Lawrence's death in 1930 (he and Maria were present at his death in Provence), Huxley edited Lawrence's letters (1932).[31] Very early in 1929, in London, Huxley met Gerald Heard, a writer and broadcaster, philosopher and interpreter of contemporary science. Heard was nearly five years older than Huxley, and introduced him to a variety of profound ideas, subtle interconnections, and various emerging spiritual and psychotherapy methods.[32]

Works of this period included novels about the dehumanising aspects of scientific progress, (his magnum opus Brave New World), and on pacifist themes (Eyeless in Gaza).[33] In Brave New World, set in a dystopian London, Huxley portrays a society operating on the principles of mass production and Pavlovian conditioning.[34] Huxley was strongly influenced by F. Matthias Alexander, on whom he based a character in Eyeless in Gaza.[35]

During this period, Huxley began to write and edit non-fiction works on pacifist issues, including Ends and Means (1937), An Encyclopedia of Pacifism, and Pacifism and Philosophy, and was an active member of the Peace Pledge Union (PPU).[36]

Life in the United States

[edit]In 1937, Huxley moved to Hollywood with his wife Maria, son Matthew Huxley, and friend Gerald Heard. Cyril Connolly wrote, of the two intellectuals (Huxley and Heard) in the late 1930s, "all European avenues had been exhausted in the search for a way forward – politics, art, science – pitching them both toward the US in 1937."[37] Huxley lived in the U.S., mainly southern California,[38][39][40] until his death, and for a time in Taos, New Mexico, where he wrote Ends and Means (1937). The book contains tracts on war,[41] inequality,[42] religion[43] and ethics.[44]

Heard introduced Huxley to Vedanta (Upanishad-centered philosophy), meditation, and vegetarianism through the principle of ahimsa. In 1938, Huxley befriended Jiddu Krishnamurti, whose teachings he greatly admired. Huxley and Krishnamurti entered into an enduring exchange (sometimes edging on debate) over many years, with Krishnamurti representing the more rarefied, detached, ivory-tower perspective and Huxley, with his pragmatic concerns, the more socially and historically informed position. Huxley wrote a foreword to Krishnamurti's quintessential statement, The First and Last Freedom (1954).[45]

Huxley and Heard became Vedantists in the group formed around Hindu Swami Prabhavananda, and subsequently introduced Christopher Isherwood to the circle. Not long afterwards, Huxley wrote his book on widely held spiritual values and ideas, The Perennial Philosophy, which discussed the teachings of renowned mystics of the world.[46][47]

Huxley became a close friend of Remsen Bird, president of Occidental College. He spent much time at the college in the Eagle Rock neighbourhood of Los Angeles. The college appears as "Tarzana College" in his satirical novel After Many a Summer (1939). The novel won Huxley a British literary award, the 1939 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction.[48] Huxley also incorporated Bird into the novel.[49]

During this period, Huxley earned a substantial income as a Hollywood screenwriter; Christopher Isherwood, in his autobiography My Guru and His Disciple, states that Huxley earned more than $3,000 per week (approximately $50,000[50] in 2020 dollars) as a screenwriter, and that he used much of it to transport Jewish and left-wing writer and artist refugees from Hitler's Germany to the US.[51] In March 1938, Huxley's friend Anita Loos, a novelist and screenwriter, put him in touch with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), which hired him for Madame Curie which was originally to star Greta Garbo and be directed by George Cukor. (Eventually, the film was completed by MGM in 1943 with a different director and cast.) Huxley received screen credit for Pride and Prejudice (1940) and was paid for his work on a number of other films, including Jane Eyre (1944). He was commissioned by Walt Disney in 1945 to write a script based on Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and the biography of the story's author, Lewis Carroll. The script was not used, however.[52]

Huxley wrote an introduction to the posthumous publication of J. D. Unwin's 1940 book Hopousia or The Sexual and Economic Foundations of a New Society.[53]

On 21 October 1949, Huxley wrote to George Orwell, author of Nineteen Eighty-Four, congratulating him on "how fine and how profoundly important the book is". In his letter, he predicted:

"Within the next generation I believe that the world's leaders will discover that infant conditioning and narcohypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging them and kicking them into obedience."[54]

In 1953, Huxley and Maria applied for United States citizenship and presented themselves for examination. When Huxley refused to bear arms for the U.S. and would not state that his objections were based on religious ideals, the only excuse allowed under the McCarran Act, the judge had to adjourn the proceedings.[55][56] He withdrew his application. Nevertheless, he remained in the U.S. In 1959, Huxley turned down an offer to be made a Knight Bachelor by the Macmillan government without giving a reason; his brother Julian had been knighted in 1958, while his brother Andrew would be knighted in 1974.[57]

In the fall semester of 1960 Huxley was invited by Professor Huston Smith to be the Carnegie Visiting professor of humanities at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).[58] As part of the MIT centennial program of events organised by the Department of Humanities, Huxley presented a series of lectures titled, "What a Piece of Work is a Man" which concerned history, language, and art.[59]

Robert S. de Ropp (scientist, humanitarian, and author), who had spent time with Huxley in England in the 1930s, connected with him again in the U.S. in the early 1960s and wrote that "the enormous intellect, the beautifully modulated voice, the gentle objectivity, all were unchanged. He was one of the most highly civilized human beings I had ever met."[60]

Late-in-life perspectives

[edit]Biographer Harold H. Watts wrote that Huxley's writings in the "final and extended period of his life" are "the work of a man who is meditating on the central problems of many modern men".[61] Huxley had deeply felt apprehensions about the future the developed world might make for itself. From these, he made some warnings in his writings and talks. In a 1958 televised interview conducted by journalist Mike Wallace, Huxley outlined several major concerns: the difficulties and dangers of world overpopulation; the tendency towards distinctly hierarchical social organisation; the crucial importance of evaluating the use of technology in mass societies susceptible to persuasion; the tendency to promote modern politicians to a naive public as well-marketed commodities.[62] In a December 1962 letter to brother Julian, summarizing a paper he had presented in Santa Barbara, he wrote, "What I said was that if we didn't pretty quickly start thinking of human problems in ecological terms rather than in terms of power politics we should very soon be in a bad way."[63]

Huxley's engagement with Eastern wisdom traditions was entirely compatible with a strong appreciation of modern science. Biographer Milton Birnbaum wrote that Huxley "ended by embracing both science and Eastern religion".[64] In his last book, Literature and Science, Huxley wrote that "The ethical and philosophical implications of modern science are more Buddhist than Christian...."[65] In "A Philosopher's Visionary Prediction", published one month before he died, Huxley endorsed training in general semantics and "the nonverbal world of culturally uncontaminated consciousness", writing that "We must learn how to be mentally silent, we must cultivate the art of pure receptivity.... [T]he individual must learn to decondition himself, must be able to cut holes in the fence of verbalized symbols that hems him in."[66]

Spiritual views

[edit]Huxley described himself as agnostic, a word coined by his grandfather Thomas Henry Huxley, a scientist who championed the scientific method and was a major supporter of Darwin's theories. This is the definition he gave, “…it is wrong for a man to say that he is certain of the objective truth of any proposition unless he can produce evidence which logically justifies that certainty.”[67] Aldous Huxley's agnosticism, together with his speculative propensity, made it difficult for him fully embrace any form of institutionalised religion.[68] Over the last 30 years of his life, he accepted and wrote about concepts found in Vedanta and was a leading advocate of the Perennial Philosophy, which holds that the same metaphysical truths are found in all the major religions of the world.[69][70][71]

In the 1920s, Huxley was skeptical of religion, "Earlier in his career he had rejected mysticism, often poking fun at it in his novels [...]"[72] Gerald Heard became an influential friend of Huxley, and since the mid-1920s had been exploring Vedanta,[73] as a way of understanding individual human life and the individual's relationship to the universe. Heard and Huxley both saw the political implications of Vedanta, which could help bring about peace, specifically that there is an underlying reality that all humans and the universe are a part of. In the 1930s, Huxley and Gerald Heard both became active in the effort to avoid another world war, writing essays and eventually publicly speaking in support of the Peace Pledge Union. But, they remained frustrated by the conflicting goals of the political left – some favoring pacifism (as did Huxley and Heard), while other wanting to take up arms against fascism in the Spanish Civil War.[74]

After joining the PPU, Huxley expressed his frustration with politics in a letter from 1935, “…the thing finally resolves itself into a religious problem — an uncomfortable fact which one must be prepared to face and which I have come during the last year to find it easier to face.”[75] Huxley and Heard turned their attention to addressing the big problems of the world through transforming the individual, "[...] a forest is only as green as the individual trees of the forest is green [...]"[73] This was the genesis of the Human Potential Movement, that gained traction in the 1960s.[76][77]

In the late 1930s, Huxley and Heard immigrated to the United States, and beginning in 1939 and continuing until his death in 1963, Huxley had an extensive association with the Vedanta Society of Southern California, founded and headed by Swami Prabhavananda. Together with Gerald Heard, Christopher Isherwood and other followers, he was initiated by the Swami and was taught meditation and spiritual practices.[13] From 1941 until 1960, Huxley contributed 48 articles to Vedanta and the West, published by the society. He also served on the editorial board with Isherwood, Heard, and playwright John Van Druten from 1951 through 1962.

In 1942 The Gospel of Ramakrishna was published by the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center in New York. The book was translated by Swami Nikhilananda, with help from Joseph Campbell and Margaret Woodrow Wilson, daughter of US president Woodrow Wilson. Aldous Huxley wrote in the foreword, "...a book unique, so far as my knowledge goes, in the literature of hagiography. Never have the small events of a contemplative's daily life been described with such a wealth of intimate detail. Never have the casual and unstudied utterances of a great religious teacher been set down with so minute a fidelity."[78][79]

In 1944, Huxley wrote the introduction to the Bhagavad Gita – The Song of God,[80] translated by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood, which was published by the Vedanta Society of Southern California. As an advocate of the perennial philosophy, Huxley was drawn to the Gita, as he explained in the Introduction, written during WWII, when it was still not clear who would win:

The Bhagavad Gita is perhaps the most systematic scriptural statement of the Perennial Philosophy. To a world at war, a world that, because it lacks the intellectual and spiritual prerequisites to peace, can only hope to patch up some kind of precarious armed truce, it stands pointing, clearly and unmistakably, to the only road of escape from the self–imposed necessity of self–destruction.[80]

As a means of personally realizing the "divine Reality", he described a "Minimum Working Hypothesis" in the Introduction to Swami Prabhavananda's and Christopher Isherwood's translation of the Bhagavad Gita and in a free-standing essay in Vedanta and the West,[81] a publication of Vedanta Press. This is the outline, that Huxley elaborates on in the article:

For those of us who are not congenitally the members of an organized church, who have found that humanism and nature-worship are not enough, who are not content to remain in the darkness of ignorance, the squalor of vice or the other squalor of respectability, the minimum working hypothesis would seem to run to about this:

That there is a Godhead, Ground, Brahman, Clear Light of the Void, which is the unmanifested principle of all manifestations.

That the Ground is at once transcendent and immanent.

That it is possible for human beings to love, know and, from virtually, to become actually identical with the divine Ground.

That to achieve this unitive knowledge of the Godhead is the final end and purpose of human existence.

That there is a Law or Dharma which must be obeyed, a Tao or Way which must be followed, if men are to achieve their final end.[81]

For Huxley, one of the attractive features of Vedanta is that it provided a historic and established philosophy and practice that embraced the Perennial Philosophy; that there is a commonality of experiences across all the mystical branches of the world's religions.[82] Huxley wrote in the introduction of his book The Perennial Philosophy:

The Perennial Philosophy is primarily concerned with the one, divine Reality substantial to the manifold world of things and lives and minds. But the nature of this one Reality is such that it cannot be directly and immediately apprehended except by those who have chosen to fulfill certain conditions, making themselves loving, pure in heart, and poor in spirit.[83]

Huxley also occasionally lectured at the Hollywood and Santa Barbara Vedanta temples. Two of those lectures have been released on CD: Knowledge and Understanding and Who Are We? from 1955.

Many of Huxley's contemporaries and critics were disappointed by Huxley's turn to mysticism;[84] Isherwood describes in his diary how he had to explain the criticism to Huxley's widow, Laura:

[December 11, 1963, a few weeks after Aldous Huxley’s death] The publisher had suggested John Lehmann should write the biography. Laura [Huxley] asked me what I thought of the idea, so I had to tell her that John disbelieves in, and is aggressive toward, the metaphysical beliefs that Aldous held. All he would describe would be a clever young intellectual who later was corrupted by Hollywood and went astray after spooks.[85]

Psychedelic drug use and mystical experiences

[edit]In early 1953, Huxley had his first experience with the psychedelic drug mescaline. Huxley had initiated a correspondence with Doctor Humphry Osmond, a British psychiatrist then employed in a Canadian institution, and eventually asked him to supply a dose of mescaline; Osmond obliged and supervised Huxley's session in southern California. After the publication of The Doors of Perception, in which he recounted this experience, Huxley and Swami Prabhavananda disagreed about the meaning and importance of the psychedelic drug experience, which may have caused the relationship to cool, but Huxley continued to write articles for the society's journal, lecture at the temple, and attend social functions. Huxley later had an experience on mescaline that he considered more profound than those detailed in The Doors of Perception.

Huxley wrote that "The mystical experience is doubly valuable; it is valuable because it gives the experiencer a better understanding of himself and the world and because it may help him to lead a less self-centered and more creative life."[86]

Having tried LSD in the 1950s, he became an advisor to Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert in their early-1960s research work with psychedelic drugs at Harvard. Personality differences led Huxley to distance himself from Leary, when Huxley grew concerned that Leary had become too keen on promoting the drugs rather indiscriminately, even playing the rebel with a fondness for publicity.[87][88]

Eyesight

[edit]

Differing accounts exist about the details of the quality of Huxley's eyesight at specific points in his life. Circa 1939, Huxley encountered the Bates method, in which he was instructed by Margaret Darst Corbett. In 1940, Huxley relocated from Hollywood to a 40-acre (16 ha) ranchito in the high desert hamlet of Llano, California, in northern Los Angeles County. Huxley then said that his sight improved dramatically with the Bates method and the extreme and pure natural lighting of the southwestern American desert. He reported that, for the first time in more than 25 years, he was able to read without glasses and without strain. He even tried driving a car along the dirt road beside the ranch. He wrote a book about his experiences with the Bates method, The Art of Seeing, which was published in 1942 (U.S.), 1943 (UK). The book contained some generally disputed theories, and its publication created a growing degree of popular controversy about Huxley's eyesight.[89]

It was, and is, widely believed that Huxley was nearly blind since the illness in his teens, despite the partial recovery that had enabled him to study at Oxford. For example, some ten years after publication of The Art of Seeing, in 1952, Bennett Cerf was present when Huxley spoke at a Hollywood banquet, wearing no glasses and apparently reading his paper from the lectern without difficulty:

Then suddenly he faltered—and the disturbing truth became obvious. He wasn't reading his address at all. He had learned it by heart. To refresh his memory he brought the paper closer and closer to his eyes. When it was only an inch or so away he still couldn't read it, and had to fish for a magnifying glass in his pocket to make the typing visible to him. It was an agonising moment.[90]

Brazilian author João Ubaldo Ribeiro, who as a young journalist spent several evenings in the Huxleys' company in the late 1950s, wrote that Huxley had said to him, with a wry smile: "I can hardly see at all. And I don't give a damn, really."[91]

On the other hand, Huxley's second wife Laura later emphasised in her biographical account, This Timeless Moment: "One of the great achievements of his life: that of having regained his sight." After revealing a letter she wrote to the Los Angeles Times disclaiming the label of Huxley as a "poor fellow who can hardly see" by Walter C. Alvarez, she tempered her statement:

Although I feel it was an injustice to treat Aldous as though he were blind, it is true there were many indications of his impaired vision. For instance, although Aldous did not wear glasses, he would quite often use a magnifying lens.[92]

Laura Huxley proceeded to elaborate a few nuances of inconsistency peculiar to Huxley's vision. Her account, in this respect, agrees with the following sample of Huxley's own words from The Art of Seeing:

The most characteristic fact about the functioning of the total organism, or any part of the organism, is that it is not constant, but highly variable.[93]

Nevertheless, the topic of Huxley's eyesight has continued to endure similar, significant controversy.[94] American popular science author Steven Johnson, in his book Mind Wide Open, quotes Huxley about his difficulties with visual encoding:

I am and, for as long as I can remember, I have always been a poor visualizer. Words, even the pregnant words of poets, do not evoke pictures in my mind. No hypnagogic visions greet me on the verge of sleep. When I recall something, the memory does not present itself to me as a vividly seen event or object. By an effort of the will, I can evoke a not very vivid image of what happened yesterday afternoon ...[95][96]

Personal life

[edit]Huxley married on 10 July 1919[97] Maria Nys (10 September 1899 – 12 February 1955), a Belgian epidemiologist from Bellem,[97] a village near Aalter, he met at Garsington, Oxfordshire, in 1919. They had one child, Matthew Huxley (19 April 1920 – 10 February 2005), who had a career as an author, anthropologist, and prominent epidemiologist.[98] In 1955, Maria Huxley died of cancer.[23]

In 1956, Huxley married Laura Archera (1911–2007), also an author, as well as a violinist and psychotherapist.[23] She wrote This Timeless Moment, a biography of Huxley. She told the story of their marriage through Mary Ann Braubach's 2010 documentary, Huxley on Huxley.[99]

Huxley was diagnosed with laryngeal cancer in 1960; in the years that followed, with his health deteriorating, he wrote the utopian novel Island,[100] and gave lectures on "Human Potentialities" both at the UCSF Medical Center and at the Esalen Institute. These lectures were fundamental to the beginning of the Human Potential Movement.[77]

Huxley was a close friend of Jiddu Krishnamurti and Rosalind Rajagopal, and was involved in the creation of the Happy Valley School, now Besant Hill School, of Happy Valley, in Ojai, California.

The most substantial collection of Huxley's few remaining papers, following the destruction of most in the 1961 Bel Air Fire, is at the Library of the University of California, Los Angeles.[101] Some are also at the Stanford University Libraries.[102]

On 9 April 1962 Huxley was informed he was elected Companion of Literature by the Royal Society of Literature, the senior literary organisation in Britain, and he accepted the title via letter on 28 April 1962.[103] The correspondence between Huxley and the society is kept at the Cambridge University Library.[103] The society invited Huxley to appear at a banquet and give a lecture at Somerset House, London, in June 1963. Huxley wrote a draft of the speech he intended to give at the society; however, his deteriorating health meant he was not able to attend.[103]

Death

[edit]In 1960, Huxley was diagnosed with oral cancer and for the next three years his health steadily declined. On November 4, 1963, less than three weeks before Huxley's death, author Christopher Isherwood, a friend of 25 years, visited in Cedars Sinai Hospital and wrote his impressions:

I came away with the picture of a great noble vessel sinking quietly into the deep; many of its delicate marvelous mechanisms still in perfect order, all its lights still shining.[104]

At home on his deathbed, unable to speak owing to cancer that had metastasized, Huxley made a written request to his wife Laura for "LSD, 100 μg, intramuscular." According to her account of his death[105] in This Timeless Moment, she obliged with an injection at 11:20 a.m. and a second dose an hour later; Huxley died aged 69, at 5:20 p.m. PST on 22 November 1963.[106]

Media coverage of Huxley's death, along with that of fellow British author C. S. Lewis, was overshadowed by the assassination of John F. Kennedy on the same day, less than seven hours before Huxley's death.[107] In a 2009 article for New York magazine titled "The Eclipsed Celebrity Death Club", Christopher Bonanos wrote:

The championship trophy for badly timed death, though, goes to a pair of British writers. Aldous Huxley, the author of Brave New World, died the same day as C. S. Lewis, who wrote the Chronicles of Narnia series. Unfortunately for both of their legacies, that day was November 22, 1963, just as John Kennedy's motorcade passed the Texas School Book Depository. Huxley, at least, made it interesting: At his request, his wife shot him up with LSD a couple of hours before the end, and he tripped his way out of this world.[108]

This coincidence served as the basis for Peter Kreeft's book Between Heaven and Hell: A Dialog Somewhere Beyond Death with John F. Kennedy, C. S. Lewis, & Aldous Huxley, which imagines a conversation among the three men taking place in Purgatory following their deaths.[109]

Huxley's memorial service took place in London in December 1963; it was led by his elder brother Julian. On 27 October 1971,[110] his ashes were interred in the family grave at the Watts Cemetery, home of the Watts Mortuary Chapel in Compton, Guildford, Surrey, England.[111]

Huxley had been a long-time friend of Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, who dedicated his last orchestral composition to Huxley. What became Variations: Aldous Huxley in memoriam was begun in July 1963, completed in October 1964, and premiered by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on 17 April 1965.[112][113]

Awards

[edit]- 1939: James Tait Black Memorial Prize (for After Many a Summer Dies the Swan).[114]

- 1959: American Academy of Arts and Letters Award of Merit (for Brave New World).[115][116]

- 1962: Companion of Literature (Royal Society of Literature)[117]

Commemoration

[edit]In 2021, Huxley was one of six British writers commemorated on a series of UK postage stamps issued by Royal Mail to celebrate British science fiction.[118] One classic science fiction novel from each author was depicted, with Brave New World chosen to represent Huxley.[118]

Publications and adaptations

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Watt, Donald, ed. (1975). Aldous Huxley. Routledge. p. 366. ISBN 978-0-415-15915-9.

Inge's agreement with Huxley on several essential points indicates the respect Huxley's position commanded from some important philosophers ... And now we have a book by Aldous Huxley, duly labelled The Perennial Philosophy. ... He is now quite definitely a mystical philosopher.

- ^ Sion, Ronald T. (2010). Aldous Huxley and the Search for Meaning: A Study of the Eleven Novels. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7864-4746-6.

Aldous Huxley, as a writer of fiction in the 20th century, willingly assumes the role of a modern philosopher-king or literary prophet by examining the essence of what it means to be human in the modern age. ... Huxley was a prolific genius who was always searching throughout his life for an understanding of self and one's place within the universe.

- ^ Reiff 2009, p. 7: "He was also a philosopher, mystic, social prophet, political thinker, and world traveler who had a detailed knowledge of music, medicine, science, technology, history, literature and Eastern religions."

- ^ Sawyer 2002, p. 187: "Huxley was a philosopher but his viewpoint was not determined by the intellect alone. He believed the rational mind could only speculate about truth and never find it directly."

- ^ Reiff 2009, p. 101.

- ^ Dana Sawyer in M. Keith Booker (ed.), Encyclopedia of Literature and Politics: H–R, Greenwood Publishing Group (2005), p. 359

- ^ "The Britons who made their mark on LA". The Daily Telegraph. 11 September 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ a b Thody 1973.

- ^ "Nomination Database: Aldous Huxley". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Companions of Literature". Royal Society of Literature. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Poller 2019, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Dunaway, David K. (1995). Aldous Huxley Recollected: An Oral History. Rowman Altamira. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-7619-9065-9.

- ^ a b Roy, Pothen & Sunita 2003.

- ^ "Mr Aldous Huxley". The Times. No. 55867. London. 25 November 1963. p. 14.

- ^ Susser, Eric (2006). Grayling, A.C.; Goulder, Naomi; Pyle, Andrew (eds.). "Huxley, Aldous Leonard". The Continuum Encyclopedia of British Philosophy. Continuum. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199754694.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-975469-4. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

Aldous Huxley was born in Godalming, Surrey on 26 July 1894 and died in Los Angeles, California on 17 December

- ^ "Cornhill Magazine". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Sutherland, John (1990) Mrs Humphry Ward: Eminent Victorian, Pre-eminent Edwardian. Clarendon Press, p. 167.

- ^ Holmes, Charles Mason (1978) Aldous Huxley and the Way to Reality. Greenwood Press, 1978, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Bedford, Sybille (1974). Aldous Huxley. Alfred A. Knopf / Harper & Row.

- ^ Hull, James (2004). Aldous Huxley, Representative Man. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 6. ISBN 978-3-8258-7663-0.

- ^ M.C. Rintoul (5 March 2014). Dictionary of Real People and Places in Fiction. Taylor & Francis. p. 509. ISBN 978-1-136-11940-8.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (1939). "Biography and bibliography (appendix)". After Many A Summer Dies The Swan. 1st Perennial Classic. Harper & Row. p. 243.

- ^ a b c Huxley, Aldous (2006). "Aldous Huxley: A Life of the Mind". Brave New World. Harper Perennial Modern Classics / HarperCollins Publishers.

- ^ a b c Reiff 2009, p. 112.

- ^ Julian Huxley 1965. Aldous Huxley 1894–1963: a Memorial Volume. Chatto & Windus, London. p. 22

- ^ Crick, Bernard (1992). George Orwell: A Life. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-014563-2.

- ^ "Brave New World (1932)", Aldous Huxley : A Study of the Major Novels, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013, doi:10.5040/9781472553942.ch-007, ISBN 978-1-4725-1173-7, retrieved 7 October 2023

- ^ Sexton 2007, p. 144.

- ^ Weber, Michel (March 2005), Meckier, Jerome; Nugel, Bernfried (eds.), "On Religiousness and Religion. Huxley's Reading of Whitehead's Religion in the Making in the Light of James' Varieties of Religious Experience", Aldous Huxley Annual. A Journal of Twentieth-Century Thought and Beyond, vol. 5, Münster: LIT, pp. 117–132.

- ^ Clark, Ronald W (1968), The Huxleys, London: William Heinemann.

- ^ Woodcock, George (2007). Dawn and the Darkest Hour: A Study of Aldous Huxley. Black Rose Books. p. 240..

- ^ Murray, Nicholas (4 June 2009). Aldous Huxley: An English Intellectual. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-7481-1231-9.

- ^ Vitoux, Peter (1972). "Structure and Meaning in Aldous Huxley's 'Eyeless in Gaza'". The Yearbook of English Studies. 2: 212–224. doi:10.2307/3506521. JSTOR 3506521.

- ^ Firchow, Peter (1975). "Science and Conscience in Huxley's "Brave New World"". Contemporary Literature. 16 (3): 301–316. doi:10.2307/1207404. JSTOR 1207404.

- ^ Watts Estrich, Helen (1939). "Jesting Pilate Tells the Answer: Aldous Huxley". The Sewanee Review. 47 (1): 63–81. JSTOR 27535511.

- ^ "Aldous Huxley". Peace Pledge Union. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ^ Bucknell, Katherine (28 February 2014). "Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood: Writing the Script for Gay Liberation". LARB Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ^ Symons, Allene (2015). Aldous Huxley's Hands: His Quest for Perception and the Origin and Return of Psychedelic Science. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-63388-116-7.

- ^ "a book review by Stephen Hren: Aldous Huxley's Hands: His Quest for Perception and the Origin and Return of Psychedelic Science". nyjournalofbooks.com. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "'Aldous Huxley Slept Here' – Illustrated Talk October 12 at West Hollywood Library". Larchmont Buzz. 8 October 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Huxley 1937, Chapter IX: War.

- ^ Huxley 1937, Chapter XI: Inequality.

- ^ Huxley 1937, Chapter XIII: Religious practices; Chapter XIV: Beliefs.

- ^ Huxley 1937, Chapter XV: Ethics.

- ^ Vernon, Roland (2000). Star in the East. Boulder, CO: Sentient Publications. pp. 204–207. ISBN 978-0-0947-6480-4.

- ^ Chandra Roy, Bidhan (2020). "Chapter 14: In Search of a Spiritual Home: Christopher Isherwood, The Perennial Philosophy, and Vedanta". In Berg, James J.; Freeman, Chris (eds.). Isherwood in Transit. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 190–201. doi:10.5749/j.ctv1220r9f.18. ISBN 978-1-5179-0910-9. JSTOR 10.5749/j.ctv1220r9f.18. S2CID 225709456.

- ^ Robb, David (1985). "Brahmins from abroad: English expatriates and spiritual consciousness in modern America". American Studies. 26 (2): 45–60. JSTOR 40641960.

- ^ Reiff 2009, p. 113.

- ^ "Aldous Huxley".

- ^ "$3,000 in 1937 → 2020 | Inflation Calculator". www.in2013dollars.com. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Isherwood, Christopher (2013) [1980]. My Guru and His Disciple. London: Vintage Books. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-0995-6123-1.

- ^ "7 unproduced screenplays by famous intellectuals". Salon. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Unwin, JD (1940), Hopousia or The Sexual and Economic Foundations of a New Society, NY: Oscar Piest.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (1969). Grover Smith (ed.). Letters of Aldous Huxley. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-1312-4.

- ^ Reiff 2009, p. 31.

- ^ Murray, Nicholas (4 June 2009). Aldous Huxley: An English Intellectual. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-7481-1231-9.

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica. (2003). Volume 6. p. 178

- ^ Boyce, Barry (3 January 2017). "Huston Smith's Fifty Years on the Razor's Edge". Lion's Roar. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ "Aldous Huxley lecture series, "What a Piece of Work Is a Man"". archivesspace.mit.edu. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ Ropp, Robert S. de, Warrior's Way: a Twentieth Century Odyssey (Nevada City, CA: Gateways, 2002). p 247

- ^ Watts, Harold H. (1969). Aldous Huxley. Twayne Publishers. pp. 85–86.

- ^ "The Mike Wallace Interview: Aldous Huxley (18 May 1958)". 25 July 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2013 – via YouTube.

- ^ Sexton 2007, p. 485.

- ^ Birnbaum, Milton (1971). Aldous Huxley's Quest for Values. University of Tennessee Press. p. 407. ISBN 0-87049-127-X.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (1963). Literature and Science. Harper & Row. p. 109.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (November 1963). "A Philosopher's Visionary Prediction". Playboy. Chicago. pp. 175–179.

- ^ Collected Essays of TH Huxley | Agnosticism and Christianity, 1899

- ^ Michel Weber, "Perennial Truth and Perpetual Perishing. A. Huxley's Worldview in the Light of A. N. Whitehead's Process Philosophy of Time", in Bernfried Nugel, Uwe Rasch and Gerhard Wagner (eds.), Aldous Huxley, Man of Letters: Thinker, Critic and Artist, Proceedings of the Third International Aldous Huxley Symposium Riga 2004, Münster, LIT, Human Potentialities, vol. 9, 2007, pp. 31–45.

- ^ Sawyer 2002, pp. 97–98, 114–115, 124–125.

- ^ Murray 2003, p. 332.

- ^ Poller 2021.

- ^ Sawyer 2002, p. 94.

- ^ a b Sawyer 2002, p. 92.

- ^ Mason, Emily (2017). Democracy, Deeds and Dilemmas: Support for the Spanish Republic Within British Civil Society, 1936-1939. Sussex Academic Press. p. 65. ISBN 9781845198855.

- ^ Smith, Grover (1969). Letters of Aldous Huxley. Harper & Row. p. 398. ISBN 978-1199770608.

- ^ Poller 2021, p. 177.

- ^ a b Kripal, Jeffrey (2007). Esalen America and the Religion of No Religion. University of Chicago Press.excerpt.

- ^ Gospel of Ramakrishna page v

- ^ Lex Hixon. "Introduction". Great Swan. p. xiii.

- ^ a b Isherwood, Christopher; Swami Prabhavananda; Aldous, Huxley (1987). Bhagavad Gita: The Song of God. Hollywood, California: Vedanta Press. ISBN 978-0-87481-043-1.

- ^ a b Huxley, Aldous (1944). "Minimum Working Hypothesis". Vedanta and the West. 7 (2): 38.

- ^ Poller 2021, p. 93.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (1946). The Perennial Philosophy. Chatto & Windus. p. 38.

- ^ Enroth, Clyde (1960). "Mysticism in Two of Aldous Huxley's Early Novels". Twentieth Century Literature. 6 (3): 123–132. doi:10.2307/441011. JSTOR 441011.

- ^ Isherwood, Christopher (2010). The Sixties - Diaries Volume Two 1960 - 1969, Edited and Introduced by Katherine Bucknell. Chatto & Windus. p. 299. ISBN 9780701169404.

- ^ Huxley, "Moksha: Aldous Huxley's Classic Writings on Psychedelics and the Visionary Experience"

- ^ Huxley, Aldous letter 26 December 1962 to Humphry Osmond, in Smith, Grover (1969) The Letters of Aldous Huxley. Harper and Row: New York, p. 965.

- ^ McBride, Jason "The Untapped Promise of LSD," in March 2009, The Walrus:Toronto.

- ^ Nugel, Bernfried; Meckier, Jerome (28 February 2011). "A New Look at The Art of Seeing". Aldous Huxley Annual. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 111. ISBN 978-3-643-10450-2.

- ^ Cerf, Bennett (12 April 1952), The Saturday Review (column), quoted in Gardner, Martin (1957). Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-20394-2.

- ^ O Conselheiro Come (in Portuguese). Editora Nova Fronteira. 2000. p. 92. ISBN 978-85-209-1069-6.

- ^ Huxley, Laura (1968). This Timeless Moment. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 978-0-89087-968-9.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (n.d.). "The Art of Seeing".

- ^ Rolfe, Lionel (1981) Literary LA p. 50. Chronicle Books, 1981. University of California.

- ^ Huxley, The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell, Harper Perennial, 1963, p. 15.

- ^ Johnson, Steven (2004). Mind Wide Open: Your Brain and the Neuroscience of Everyday Life. New York: Scribner. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-7432-4165-6.

- ^ a b "Aldous Huxley (Author)". OnThisDay.com. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ "Author, NIMH Epidemiologist Matthew Huxley Dies at 84". 17 February 2005 The Washington Post

- ^ Braubach, Mary Ann (2010). "Huxley on Huxley". Cinedigm. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Peter Bowering Aldous Huxley: A Study of the Major Novels, p. 197, Oxford University Press, 1969

- ^ "Finding Aid for the Aldous and Laura Huxley papers, 1925–2007". Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ "Guide to the Aldous Huxley Collection, 1922–1934". Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ a b c Peter Edgerly Firchow, Hermann Josef Real (2005). The Perennial Satirist: Essays in Honour of Bernfried Nugel, Presented on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday, p. 1. LIT Verlag Münster

- ^ Isherwood, Christopher (1980). My Guru and His Disciple. Farrar Straus Giroux. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-374-21702-0.

- ^ "Account of Huxley's death on Letters of Note". Lettersofnote.com. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ Reiff 2009, p. 35.

- ^ Nicholas Ruddick (1993). "Ultimate Island: On the Nature of British Science Fiction". p. 28. Greenwood Press

- ^ Bonanos, Christopher (26 June 2009). "The Eclipsed Celebrity Death Club". New York. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ Kreeft, Peter (1982). Between Heaven and Hell: A Dialog Somewhere Beyond Death with John F. Kennedy, C. S. Lewis & Aldous Huxley. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. back cover. ISBN 978-0-87784-389-4.

On November 22, 1963, three great men died within hours of each other: C. S. Lewis, John F. Kennedy, and Aldous Huxley. All three believed, in different ways, that death is not the end of human life. Suppose they were right, and suppose they met after death. How might the conversation go?

- ^ Murray 2003, p. 455.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 22888). McFarland & Company. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Spies 1965, p. 62.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 534, 536–537.

- ^ "Fiction winners - Winners of the James Tait Black Prize for Fiction". The University of Edinburgh. 26 July 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (1969). Brave New World. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-083095-3.

- ^ "All Awards". American Academy of Arts and Letters. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

The Award of Merit Medal is accompanied by $25,000 and given each year, in rotation, to outstanding American painters, short story writers, sculptors, novelists, poets, and playwrights. ... Aldous Huxley ... Novel ... 1959

- ^ Chevalier, Tracy (1997). Encyclopedia of the Essay. Routledge. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-57958-342-2.

- ^ a b "Stamps to feature original artworks celebrating classic science fiction novels". Yahoo. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

Royal Mail has released images of original artworks being issued on a new set of stamps to celebrate six classic science fiction novels by British writers.

Works cited

[edit]- Huxley, Aldous (1937). Ends and Means. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Murray, Nicholas (2003). Aldous Huxley: A Biography. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-30237-5.

- Poller, Jake (2019). "Mysticism and Pacifism". Aldous Huxley and Alternative Spirituality. Aries Book Series: Texts and Studies in Western Esotericism. Vol. 27. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 139–203. doi:10.1163/9789004406902_006. ISBN 978-90-04-40690-2. ISSN 1871-1405. OCLC 1114970799. S2CID 203391577.

- Poller, Jake (2021). Aldous Huxley. Critical Lives. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-427-7.

- Reiff, Raychel Haugrud (2009). Aldous Huxley: Brave New World. Marshall Cavendish Benchmark. ISBN 978-0-7614-4701-6.

- Roy, Sumita; Pothen, Annie; Sunita, K. S., eds. (2003). Aldous Huxley and Indian Thought. Sterling Publishers. ISBN 978-81-207-2465-5.

- Sawyer, Dana (2002). Aldous Huxley: A Biography. Crossroad Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8245-1987-2.

- Sexton, James, ed. (2007). Aldous Huxley. Selected Letters. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-1-5666-3629-2.

- Spies, Claudio (Fall–Winter 1965). "Notes on Stravinsky's Variations". Perspectives of New Music. 4 (1): 62–74. doi:10.2307/832527. JSTOR 832527.. Reprinted in Perspectives on Schoenberg and Stravinsky, revised edition, edited by Benjamin Boretz and Edward T. Cone. New York: W. W. Norton, 1972.

- Thody, Philipe (1973). Huxley: A Biographical Introduction. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-289-70188-1.

- White, Eric Walter (1979). Stravinsky: The Composer and His Works (2nd ed.). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03985-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Anderson, Jack (4 July 1982). "Ballet: Suzanne Farrell in Variations Premiere". The New York Times.

- Atkins, John (1956). Aldous Huxley: A Literary Study. J. Calder.

- Barnes, Clive (1 April 1966). "Ballet: Still Another Balanchine-Stravinsky Pearl; City Troupe Performs in Premiere Here Variations for Huxley at State Theater". The New York Times. p. 28.

- Bromer, David; Struble, Shannon (2011). Aun Aprendo: A Comprehensive Bibliography of the Writings of Aldous Leonard Huxley. Boston: Bromer Booksellers.

- Dunaway, David King (1991). Huxley in Hollywood. Anchor. ISBN 978-0-385-41591-0.

- Firchow, Peter (1972). Aldous Huxley: Satirist and Novelist. University of Minnesota Press.

- Firchow, Peter (1984). The End of Utopia: A Study of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World. Bucknell University Press.

- Fraser, Raymond; Wickes, George (Spring 1960). "Interview: Aldous Huxley: The Art of Fiction No. 24". The Paris Review. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- Grant, Patrick (1979). "Belief in mysticism: Aldous Huxley, from Grey Eminence to Island". Six Modern Authors and Problems of Belief. MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-333-26340-2.

- Huxley, Laura Archera (2001). This Timeless Moment. Celestial Arts. ISBN 0-89087-968-0.

- Levinson, Martin H. (2018). "Aldous Huxley and General Semantics" (PDF). ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 75 (3 and 4): 290–298. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- Meckier, Jerome (2006). Firchow, Peter Edgerly; Nugel, Bernfried (eds.). Aldous Huxley: Modern Satirical Novelist of Ideas. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. ISBN 3-8258-9668-4.

- Morgan, W. John (2020). "Chapter 5: Pacifism or Bourgeois Pacifism? Huxley, Orwell, and Caudwell". In Morgan, W. John; Guilherme, Alexandre (eds.). Peace and War-Historical, Philosophical, and Anthropological Perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 71–96. ISBN 978-3-030-48670-9.

- Poller, Jake (2019). Aldous Huxley and Alternative Spirituality. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-40689-6.

- Rolo, Charles J., ed. (1947). The World of Aldous Huxley. Grosset Universal Library.

- Shadurski, Maxim (2020). "Chapter 5". The Nationality of Utopia: H. G. Wells, England, and the World State. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-36733-049-1.

External links

[edit]- Aldous Huxley full interview 1958: The Problems of Survival and Freedom in America

- Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery

- "Aldous Huxley: The Gravity of Light", a film essay by Oliver Hockenhull

- Aldous Huxley at IMDb

- BBC discussion programme In our time: "Brave New World". Huxley and the novel. 9 April 2009. (Audio, 45 minutes)

- BBC In their own words series. 12 October 1958 (video, 12 mins)

- "The Ultimate Revolution" (talk at UC Berkeley, 20 March 1962)

- Huxley interviewed on The Mike Wallace Interview 18 May 1958 (video)

- Centre for Huxley Research at the University of Münster

- Aldous Huxley Papers at University of California, Los Angeles Library Special Collections

- Aldous Huxley Collection at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

- Aldous Huxley Centre Zurich - World's largest exhibition of Huxley's works.

- "Huxley on Huxley". Dir. Mary Ann Braubach. Cinedigm, 2010. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

Online editions

[edit]- Works by Aldous Huxley in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Aldous Huxley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Aldous Huxley at Open Library

- Works by or about Aldous Huxley at the Internet Archive

- Works by Aldous Leonard Huxley at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by Aldous Huxley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Aldous Huxley

- 1894 births

- 1963 deaths

- 20th-century English essayists

- 20th-century English novelists

- 20th-century English philosophers

- 20th-century English short story writers

- 20th-century mystics

- Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford

- Anti-consumerists

- Bates method

- British philosophers of culture

- British philosophers of mind

- British psychedelic drug advocates

- Duke University faculty

- English agnostics

- English emigrants to the United States

- English essayists

- English male novelists

- English male poets

- English male short story writers

- English pacifists

- English people of Cornish descent

- English satirists

- British satirical novelists

- English science fiction writers

- English short story writers

- English travel writers

- Futurologists

- Human Potential Movement

- Huxley family

- James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients

- Lost Generation writers

- Male essayists

- Neo-Vedanta

- New Age predecessors

- People educated at Eton College

- People from Godalming

- Perennial philosophy

- Philosophers of literature

- Philosophers of technology

- Writers from Los Angeles

- Writers from Taos, New Mexico

- Deaths from laryngeal cancer in the United States

- Deaths from throat cancer in California

- Burials in Surrey