Psychomania

| Psychomania | |

|---|---|

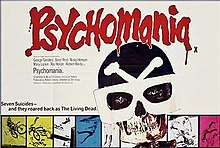

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Don Sharp |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by | Andrew Donally |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Ted Moore |

| Edited by | Richard Best |

| Music by | John Cameron |

Production company | Benmar Productions |

| Distributed by | Scotia-Barber Distributors |

Release date |

|

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

Psychomania (U.S. title:The Death Wheelers)[1] is a 1973 British outlaw biker supernatural horror film directed by Don Sharp, and starring Nicky Henson, Beryl Reid, George Sanders (in his final film), and Robert Hardy.[2][3][4]

The plot follows the adolescent leader of a biker gang, who has started practicing black magic. After meeting the Frog God, which his mother worships, the leader commits suicide on his 18th birthday. His mother resurrects him as one of the undead, and the process grants superhuman abilities to the boy. He proceeds to turn most of his gang into fellow undead, but his mother petrifies them all in a magic ritual.

Plot

[edit]Tom Latham, an amiable psychopath, is the leader of a violent youth gang named The Living Dead, which includes his girlfriend Abby. Tom dabbles in black magic and spends much of his free time at an ancient Surrey countryside ruin known as The Seven Witches, a Stonehenge-like circle of standing stones. In a similar vein, his mother and her sinister butler Shadwell get their kicks out of holding séances in their home while they worship the Frog God. Tom's father vanished in a mysterious room shortly after Tom's birth, a room Tom enters on his eighteenth birthday and where he sees the Frog God.

This incident leads to Tom committing suicide and, with his mother's help, returns from the dead. Being one of the undead means that Tom cannot be killed and has superhuman strength, which he demonstrates when he massacres those at a local pub. One by one, his fellow bikers commit suicide with the goal of returning as one of the "undead", gathering at The Seven Witches to plan their campaign of terror against the locals. Only Abby refuses to participate.

Police Chief Inspector Hesseltine is overwhelmed by the crime wave committed by bikers who are known to be dead; believing that someone is stealing the corpses of the dead bikers, he releases a false report that Abby has died. Hesseltine and his force plan to trap the culprit when he shows up to claim Abby. The Living Dead kill the policemen, while seizing Abby. However, Tom's mother, disgusted with her son's crimes, decides to break her bargain with the Frog God.

The gang tell Abby to commit suicide, but she again refuses, instead shooting Tom, who is immune. As Tom prepares to kill Abby, his mother performs a ritual that breaks the pact. Tom's mother is transformed into a frog while the undead bikers are turned into stone, becoming new statues at The Seven Witches. Abby is left alone, surrounded by those that once were her friends.

Cast

[edit]- George Sanders as Shadwell

- Beryl Reid as Mrs. Latham

- Nicky Henson as Tom Latham

- Mary Larkin as Abby Holman

- Roy Holder as Bertram

- Robert Hardy as Chief Inspector Hesseltine

- Ann Michelle as Jane Pettibone

- Denis Gilmore as Hatchet

- Miles Greenwood as Chopped Meat

- Peter Whitting as Gash

- Rocky Taylor as Hinky

- Patrick Holt as Sergeant

- Alan Bennion as Constable

- John Levene as Constable

- Roy Evans as motorist

- Bill Pertwee as publican

- Serretta Wilson as Stella

- Denis Carey as Coroner's assistant

- Lane Meddick as Mr. Pettibone

- June Brown as Mrs. Pettibone

- Fiona Kendall as Monica

- Martin Boddey as Coroner

- Heather Wright as girl with parcels

- Penny Leatherbarrow as woman in police station

- Larry Taylor as lorry driver (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Background

[edit]Psychomania was produced by Benmar Productions, best known for Spaghetti Westerns in Spain, but also made Horror Express later that same year,[5] which shares the same writers.[6] It was made in association with Scotia, who had director Don Sharp under long-term contract.[7]

Pre-production

[edit]Star Henson said, "I was a mad motorcyclist," adding "I never had a car. So this script comes through the door and I open it up and it says, ‘Eight Chopped Hog Harley Davidsons crest the brow of a hill.’ I rang my agent and said, ‘I'll do it'."[8]

Henson said when he arrived on set he saw "eight clapped-out 350 AJS’ and Matchless BSAs. I said, 'Where's the Harley Davidsons?’ They said, ‘You gotta be kidding!’ It's the only show I’ve ever been on where there were eight mechanics working the whole time to keep the bikes fanning because they got ’em in some second-hand shop somewhere and they were falling to bits."[8]

Henson said the script was written by "two expatriate Communist sympathisers" and that Sanders' scenes were shot in ten days to save money as he was paid more than the rest of the cast.[9] Henson said Sanders "was great fun on the movie. We laughed and laughed and laughed and spoiled an awful lot of takes. I mean, it must have been a nightmare for the director because we were all so young and behaving so badly and realized that we were all working on something that was kind of peripheral, that would just disappear. But of course it hasn't. That's the weird and wonderful thing about it. People come up to me in the street and quote lines from it now."[8]

Filming

[edit]Originally produced under the title The Living Dead, principal photography took place at Shepperton Studios in 1971[5] with some exterior scenes filmed in the (now demolished and rebuilt) Hepworth Way shopping centre and Wellington Close housing block in Walton-on-Thames, Surrey.[10] The stone circle was made for the film.[11]

Henson said he did all but three stunts. He says the performing stuntmen were injured following each one.[8]

Director Sharp called the film "great fun to do, especially after doing several films in a row like The Violent Enemy (1969). It was a great change, geared for a younger audience as it was."[12] Sharp recalled Sanders as "a sad man... so lonely."[13]

Sanders committed suicide soon after filming wrapped, putting an end to a period of life marked by heavy drug use, deterioration of the cerebellum and resultant speech problems.[14]

Music

[edit]The film's soundtrack, composed by John Cameron, was released on LP and CD in 2003 by Trunk Records.[15][16]

Cameron later said, "“I knew we needed a score that was spooky and different but had kind of a rock feeling to it and it was kind of pre-synthesizer... We had to use Shepperton's recording studios and it hadn't been updated since before the war. The hilarious thing is actually having these hooligan musicians all trying to do strange things, scratch inside pianos and turn sounds inside out, but the recording engineer still had a suit and tie on. It was so anachronistic."[8]

Two of Cameron's score pieces — "Witch Hunt (Title Theme from the Film Psychomania)" and "Living Dead (Theme from the Film Psychomania)" — were released in 1973 as a 7" single on the Jam label, using the artist name "Frog". This Frog record was reissued in 2011 by Spoke Records as a limited edition vinyl 7".[17]

Reception

[edit]The initial reception was mixed (one reviewer for The Times even wrote that the film was only fit to be shown at an "SS reunion party"), but over time, the film has come to be more highly regarded.[5] It holds a rating of 86% at Rotten Tomatoes based on 7 reviews.[18]

The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote:

Although a few moments (the shimmering, ghostly credits sequence, with the motorcyclists silently encircling the druid stones) recall the gloomy beauty of his earlier films, Sharp has wisely decided to treat his material here as black comedy rather than horror. He is careful not to let the tone slip into farce and to keep the action as realistic as possible; and the result of his poker-faced direction is that a ludicrous plot ... emerges as both innovatory and humorously macabre. The film has its limitations (it was evidently made on a modest budget), but it develops its central idea with enjoyable consistency and sometimes achieves images of startling comic originality ... Sharp's talent for stunt-work also ensures that the gang's hell-raising activities are convincingly exciting, and the kids' joyous obsession with death sometimes seems like an eerie extension of the whole Hell's Angel ethic (itself prefigured in Cocteau's representation of death as a black-leathered motorcyclist in Orphée). Psychomania is at its worst when attempting to delineate the motorcycle gang as individuals, and this makes the beginning rather heavy going. ... But once the plot takes over, the action is sufficiently well handled to make up for these inadequacies. ... Hopefully, we won't have to wait another six years for Sharp's next venture in the field.[19]

The Radio Times Guide to Films gave the film 3/5 stars, writing: "This British horror cheapie is so ridiculous it works. For much of the time this psychedelic zombie biker frightener is utter drivel, but director Don Sharp throws in some cracking scenes, notably the one in which leader of the gang Nicky Henson rises from the grave, bike and all. Henson has a hoot as the Angel from Hell, and he is superbly supported by Bery Reid as his devil-worshipping mum and George Sanders as his ghoulish butler."[20]

Leslie Halliwell said: "Arrant nonsense of the macabre sort, sometimes irresistably amusing."[21]

Shock Till You Drop called the film "a great one-shot horror movie filled with weird, sometimes eerie atmosphere, crazy stunt work, cheeky performances, mild kink and a unique charm all its own".[22] Variety called it "a low-budget, well-done shocker with a tightly-knit plot and a believable surprise ending".[23] Nerdist called it "very effective thanks to the mixture of heavy action, moody guitar music, and dreamy visuals."[24]

Henson said "At that time, I thought if you do dodgy films, nobody pays to see dodgy films. Of course, you're not realizing that years later they come out on DVD and become 'cults'."[8] However, film historian/director Bruce G. Hallenback stated in a book published before it was released on DVD that the film already had a cult following.[25]

Home media

[edit]Severin Films released a restored print on DVD in 2010.[26] In 2024, Severin included the film on the first disc in its folk horror Blu-ray collection All the Haunts Be Ours, Volume Two, sourced from a 4K scan of the original camera negative.

BFI Flipside released a dual-format Blu-ray/DVD edition in the EU on 26 September 2016.[27]

Arrow Films released a dual-format Blu-ray/DVD edition in the USA on 22 February 2017.[28]

References

[edit]- ^ Hischak, Thomas S. (2015). The Encyclopedia of Film Composers. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 115. ISBN 978-1442245495.

- ^ "Psychomania". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ PSYCHOMANIA Monthly Film Bulletin; London Vol. 40, Iss. 468, (Jan 1, 1973): 82.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (27 July 2019). "Unsung Aussie Filmmakers: Don Sharp – A Top 25". Filmink.

- ^ a b c Smith, Adrian (2016), "Psychomania", Screem, 1 (32): 14–16

- ^ *Hodges, Mike (September 1999). "Riding the Horror Express". Fangoria. No. 186. pp. 70–75.

- ^ Sharp, Don (2 November 1993). "Don Sharp Side 5" (Interview). Interviewed by Teddy Darvas and Alan Lawson. London: History Project. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Andrews, Stuart (November 2010). "Hell Bent for Leather". Rue Morgue. p. 49.

- ^ Alexander, Chris (October 2010). "Born to Be Undead: Psychomania". Fangoria. No. 297.

- ^ "Psychomania Locations". Psychomania.bondle.co.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Stone circles: 10 staggering standing-stones on screen". BFI. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ The Midnight Writer (December 1983). "Sharp Turns". Fangoria. No. 31. pp. 14–18. [dead link]

- ^ Sharp, Don (2 November 1993). "Don Sharp Side 6" (Interview). Interviewed by Teddy Darvas and Alan Lawson. London: History Project. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Fowler, William (2017). The Last Movie: George Sanders And Psychomania (Media notes). Arrow Video. p. 12.

- ^ "Psychomania: Amazon.co.uk: Music". Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Psychomania". Trunkrecords.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Spoke Releases: Home Page". Spokerecords.co.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Psychomania at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ "Psychomania". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 40 (468): 82. 1 January 1973. ProQuest 1305830737 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Radio Times Guide to Films (18th ed.). London: Immediate Media Company. 2017. p. 744. ISBN 9780992936440.

- ^ Halliwell, Leslie (1989). Halliwell's Film Guide (7th ed.). London: Paladin. p. 822. ISBN 0586088946.

- ^ Alexander, Chris (23 February 2017). "Psychomania Blu-ray Review". Shock Till You Drop. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Review: 'Psychomania'". Variety. 31 December 1963. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Anderson, Kyle (23 February 2017). "Schlock & Awe: PSYCHOMANIA". Nerdist. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Hallenbeck, Bruce G. (2009). Comedy-Horror Films: A Chronological History, 1914-2008. McFarland & Company. pp. 93–94. ISBN 9780786453788.

- ^ "PSYCHOMANIA STREETS TODAY, PRESS ROUND-UP PART 1". Severin Films. 26 December 2010. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Buy Psychomania (Flipside 033) (Dual Format Edition) - Shop". shop.bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "NEW US TITLE: Psychomania Dual Format Blu-ray & DVD". Facebook. 11 November 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

External links

[edit]- Psychomania at IMDb

- Psychomania at Rotten Tomatoes

- Psychomania at Letterbox DVD

- Essay on film at Diabolique

- Essay on film at Dangerous Minds

- Essay on film at Film Inquiry

- Essay on film at Senses of Cinema

- 1973 films

- 1973 horror films

- 1970s supernatural horror films

- British supernatural horror films

- Films about suicide

- Outlaw biker films

- Films directed by Don Sharp

- Films scored by John Cameron (musician)

- Films with screenplays by Arnaud d'Usseau

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s British films

- Films about magic

- Films set in Surrey

- Films about birthdays

- Resurrection in film

- Films about deities

- Films about frogs

- Films about mother–son relationships

- Films about filicide

- Films about undead

- English-language horror films