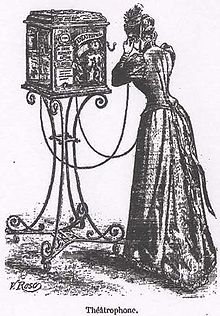

Théâtrophone

Théâtrophone (French pronunciation: [teatʁɔfɔn], "the theatre phone") was a telephonic distribution system available in portions of Europe that allowed the subscribers to listen to opera and theatre performances over the telephone lines. The théâtrophone evolved from a Clément Ader invention, which was first demonstrated in 1881, in Paris. Subsequently, in 1890, the invention was commercialized by Compagnie du Théâtrophone, which continued to operate until 1932.

Origin

[edit]

The origin of the théâtrophone can be traced to a telephonic transmission system demonstrated by Clément Ader at the 1881 International Exposition of Electricity in Paris. The system was inaugurated by the French President Jules Grévy, and allowed broadcasting of concerts or plays. Ader had arranged 80 telephone transmitters across the front of a stage to create a form of binaural stereophonic sound.[1] It was the first two-channel audio system, and consisted of a series of telephone transmitters connected from the stage of the Paris Opera to a suite of rooms at the Paris Electrical Exhibition, where the visitors could hear Comédie-Française and opera performances in stereo using two headphones; the Opera was located more than two kilometers away from the venue.[2] In a note dated 11 November 1881, Victor Hugo describes his first experience of théâtrophone as pleasant.[3][4]

In 1884, the King Luís I of Portugal decided to use the system, when he could not attend an opera in person. The director of the Edison Gower Bell Company, who was responsible for this théâtrophone installation, was later awarded the Military Order of Christ.[5]

The théâtrophone technology was made available in Belgium in 1884, and in Lisbon in 1885. In Sweden, the first telephone transmission of an opera performance took place in Stockholm in May 1887. The British writer Ouida describes a female character in the novel Massarenes (1897) as "A modern woman of the world. As costly as an ironclad and as complicated as theatrophone."[5]

The Théâtrophone service

[edit]

In 1890, the system became operational as a service under the name "théâtrophone" in Paris. The service was offered by Compagnie du Théâtrophone (The Théâtrophone Company), which was founded by MM. Marinovitch and Szarvady.[5] The théâtrophone offered theatre and opera performances to the subscribers. The service can be called a prototype of the telephone newspaper, as it included five-minute news programs at regular intervals.[7] The Théâtrophone Company set up coin-operated telephone receivers in hotels, cafés, clubs, and other locations, costing 50 centimes for five minutes of listening.[8] The subscription tickets were also issued at a reduced rate, in order to attract regular patrons. The service was also available to home subscribers.

French writer Marcel Proust was a keen follower of théâtrophone, as evident by his correspondence. He subscribed to the service in 1911.[9][10]

Many technological improvements were gradually made to the original théâtrophone system. The Brown telephone relay, invented in 1913, yielded interesting results for amplification of the current.[5]

The théâtrophone finally succumbed to the rising popularity of radio broadcasting and the phonograph, and the Compagnie du Théâtrophone ceased its operations in 1932.[5]

Similar systems

[edit]Similar systems elsewhere in Europe included Telefon Hírmondó (est. 1893) of Budapest and Electrophone of London (est. 1895). In the United States, the systems similar to théâtrophone were limited to one-off experiments. Erik Barnouw reported a concert by telephone that was organized in the summer of 1890; around 800 people at the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga listened to a telephonic transmission of The Charge of the Light Brigade conducted at Madison Square Garden.[5]

In fiction

[edit]The Andrew Crumey novel Mr Mee (2000) has a chapter depicting the installation of a théâtrophone in the home of Marcel Proust.

The Eça de Queiroz novel A Cidade e as Serras (1901) mentions the device as one of the many technological commodities available for the distraction of the upper classes.

In his utopian science fiction novel Looking Backward (1888), Edward Bellamy predicted sermons and music being available in the home through a system like théâtrophone.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Chronomedia: 1880-1884". Terra Media. 20 November 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ A. Lange (March 31, 2002). "Le Premier Medium Electrique De Diffusion Culturelle: Le Theatrophone De Clement Ader (1881)" (in French). Histoire de la télévision. Archived from the original on 2015-12-20. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ A. Lange (31 March 2002). "Victor Hugo, Premier Temoin Du Theatrophone" (in French). Histoire de la télévision. Archived from the original on 2015-12-20. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ Hugo, Victor (1951). Choses vues. Ottawa: Le Cercle du Livre de France. OCLC 883063.

- ^ a b c d e f A. Lange (4 February 2002). "Les Ecrivains Et Le Theatrophone" (in French). Histoire de la télévision. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ "How the Parisian Enjoys Opera at Home" by Frederic M. Delano, Scientific American, September 1925, page 174.

- ^ "Wanted, A Theatrophone". The Electrical Engineer: 4. 5 July 1890. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ "The Theatrophone". The Electrical Engineer. London: 161. 30 August 1889. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ A. Lange (5 January 2002). "Marcel Proust, Amateur De Theatrophone" (in French). Histoire de la télévision. Archived from the original on 2015-12-21. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ Luc Fraisse, ed. (1996). Proust au miroir de sa correspondance. Paris: SEDES. ISBN 978-2-7181-9340-3. OCLC 36309265.

External links

[edit]- Le Premier Medium Electrique De Diffusion Culturelle: Le Theatrophone De Clement Ader Archived 2015-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, "The First Electric Medium Distribution Of Culture: The Theatrophone Of Clement Ader (1881)", in French

- A 1271x1551 image of a théâtrophone instrument from La collection de Jean-Louis

- Danièle Laster. Splendeurs et misères du théâtrophone (in French).

- 1881 establishments in France

- 1890 establishments in France

- 1932 disestablishments in France

- Products introduced in 1890

- Products and services discontinued in 1932

- French inventions

- Information by telephone

- Culture of France

- Telecommunications systems

- Telephony

- Telephone newspapers

- Music mass media

- Drama by medium