Texture (visual arts)

In the visual arts, texture refers to the perceived surface quality of a work of art. It is an element found in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional designs, and it is characterized by its visual and physical properties. The use of texture, in conjunction with other design elements, can convey a wide range of messages and evoke various emotions.

Physical

[edit]

The physical texture, also known as actual texture or tactile texture, refers to the patterns of variations found on a solid surface. These can encompass a wide range of materials, including but not limited to fur, canvas, wood grain, sand, leather, satin, eggshell, matte, or smooth surfaces like metal or glass.

Physical texture differentiates itself from visual texture by having a physical quality that can be felt by touching the surface. The specific use of texture can impact the perceived smoothness or roughness conveyed by an artwork. For instance, rough surfaces can create a visually active effect, while smooth surfaces can evoke a visually restful sensation. Both types of texture can be employed to imbue a design with a sense of personality or utilized to create emphasis, rhythm, contrast, and other artistic effects.[1]

Light plays a crucial role in perceiving the physical texture as it can significantly influence how a surface is viewed. Strong lighting on a smooth surface can obscure the readability of a drawing or photograph, whereas it can create pronounced contrasts on a highly textural surface like river rocks or sand.

Visual

[edit]Visual texture or implied texture is the illusion of having physical texture. Every material and every support surface has its own visual texture and needs to be taken into consideration before creating a composition. As such, materials such as canvas and watercolour paper are considerably rougher than, for example, photo-quality computer paper and may not be best suited to creating a flat, smooth texture. Photography, drawings and paintings use visual texture both to portray their own subject matter realistically and with interpretation. Texture in these media is generally created by the repetition of the shape and line. Another example of visual texture is terrazzo or an image in a mirror.

Decorative

[edit]Decorative texture "decorates a surface". Texture is added to embellish the surface either that usually contains some uniformity.

Spontaneous

[edit]This focuses more on the process of the visual creation; the marks of texture made also creates the shapes. These are often "accidental" forms that create texture.

Mechanical

[edit]Texture created by special mechanical means. An example of this would be photography; the grains and/or screen pattern that is often found in printing creates texture on the surface. This is also exemplified by designs in typography and computer graphics.

Hypertexture

[edit]Hypertexture can be defined as both the "realistic simulated surface texture produced by adding small distortions across the surface of an object"[2] (as pioneered by Ken Perlin) and as an avenue for describing the fluid morphic nature of texture in the realm of cyber graphics and the tranversally responsive works created in the field of visual arts therein (as described by Lee Klein).[3]

Examples of physical texture

[edit]-

Berlin Green Head, 500BC. Note the smooth texture and mood of the bust.

-

Detail of woven fibers of a carpet

-

Blades of grass provides a soft texture

-

Rough bark on the surface of a tree

-

A wall of bricks with raised areas

-

Auto Texture created over Clear glass Bricks

Examples of visual texture

[edit]-

View From the Window at Le Gras, Nicéphore Niépce, 1826. Photography.

-

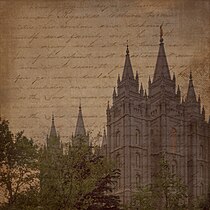

An image that has been digitally altered to show text and paper texture over a photograph

See also

[edit]- Composition (visual arts)

- Design elements and design principles

- Elements of art

- Texture mapping

- Art movement

- Creativity techniques

- List of art media

- List of artistic media

- List of art movements

- List of art techniques

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Gatto. Exploring Visual Design: The Elements and Principles. pp. 122–123.

- ^ "What does HYPERTEXTURE mean?". Definitions.net. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ^ "Hypertexture | A Gathering of the Tribes". Tribes.org. 2006-10-01. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

Sources

[edit]- Gatto, Porter, and Selleck. Exploring Visual Design: The Elements and Principles. 3rd ed. Worcester: Davis Publications, Inc., 2000. ISBN 0-87192-379-3

- Stewart, Mary, Launching the imagination: a comprehensive guide to basic design. 2nd ed. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2006. ISBN 0-07-287061-3