Ebony (magazine)

| |

| Former editors |

|

|---|---|

| Categories | Lifestyle magazine |

| Frequency | Monthly |

| Total circulation (2017) | 1,333,421[1] |

| Founder | John H. Johnson |

| First issue | November 1, 1945[2] |

| Company | Ebony Media Operations, LLC (2016–present) Johnson Publishing Company (1945–2016) |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. (2020-Present) Los Angeles, California, U.S.[3] (2017–2020) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. (1945–2017) |

| Language | English |

| Website | www |

| ISSN | 0012-9011 |

Ebony is a monthly magazine that focuses on news, culture, and entertainment. Its target audience is the African-American community, and its coverage includes the lifestyles and accomplishments of influential black people, fashion, beauty, and politics.[4][5]

Ebony magazine was founded in Chicago in 1945 by John H. Johnson, for his Johnson Publishing Company. He sought to address African-American issues, personalities and interests in a positive and self-affirming manner.[6] Its cover photography typically showcases African-American public figures, including entertainers and politicians, such as Dorothy Dandridge, Lena Horne, Diana Ross, Michael Jackson, former U.S. Senator Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois, U.S. first lady Michelle Obama, Beyoncé, Tyrese Gibson, and Tyler Perry. Each year, Ebony selects the "100 Most Influential Blacks in America".[7]

After 71 years, in June 2016, Johnson Publishing sold both Ebony and Jet, another Johnson publication, to a private equity firm called Clear View Group. The new publisher is known as Ebony Media Corporation.[8][9] After the publication went bankrupt in July 2020, it was purchased for $14 million by Junior Bridgeman in December 2020.

History

[edit]1945–1969

[edit]Ebony was founded by John H. Johnson in 1945. The magazine was named by Johnson's wife, Eunice Walker Johnson, thinking of the dark wood.[10] The magazine was patterned after the format of Life magazine.[11] Ebony published its first issue on November 1, 1945, with an initial press run of 25,000 copies that sold out completely.[12] Ebony's earlier content focused on African-American sports and entertainment figures, but eventually began including black achievers and celebrities of many different professions.[13]

Editors stated in the first issue:

We like to look at the zesty side of life. Sure, you can get all hot and bothered about the race question (and don't think we don't), but not enough is said about all the swell things we Negroes can do and will accomplish. Ebony will try to mirror the happier side of Negro life – the positive, everyday achievements from Harlem to Hollywood. But when we talk about race as the No. 1 problem of America, we'll talk turkey.[14]

During the 1960s, the magazine increasingly covered the civil rights movement. Articles were published about political events happening all over the U.S. where activists protested racial violence and advocated for increasing social mobility for African Americans across the diaspora. Also published was content about the Black Power movement. In 1965, executive editor Lerone Bennett Jr. wrote a recurring column entitled "Black Power", which featured an in-depth profile of Stokely Carmichael in 1966.[15] Ebony also commemorated historical events that contributed to black citizenship and freedom such as the September 1963 issue that honored the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.[16]

1969–1985

[edit]Ebony's design and content began to shift in the late–1960s and early–1970s. A new level of competition for subscribers and readers began during the 1970s. Due to the emergence of new African-American oriented magazines such as Essence, Ebony began to cover more political activism and achievements in the 1970s. The magazine's February 1971 cover featured 13 black congressmen and women. Ebony highlighted the black professionals serving in Jimmy Carter's administration in the March 1977 issue.[17]

1985–2005

[edit]The magazine reached unprecedented levels of popularity, with marketers estimating that Ebony reached over 40% of the African-American adults in the United States during the 1980s, a feat unmatched by any other general–interest magazine at the time.[18] Beginning in the mid-1970s, advertisers created customized ads for the magazine which featured African-American models using their products.[19] In 1985, Ebony Man, a monthly men's magazine was created, printing the first issue in September 1985.[5] By Ebony's 40th anniversary in November 1985, it had a circulation of 1.7 million.[14]

2005–present

[edit]In December 2008, Google announced that it was scanning back issues for Google Book Search. As of that date, all issues from November 1959 to December 2008 were made available for free.[20]

In 2010, the Johnson Publishing Company sold its historic building at 820 S. Michigan Avenue in Chicago's South Loop to Columbia College Chicago. The same year, Ebony was redesigned to update its longtime brand. In the past, the magazine was persistently upbeat, much like its postwar contemporary Life magazine. However, in the 21st century, Ebony featured more controversial content.

The November 2011 cover featured a pregnant Nia Long, reminiscent of the iconic image of actress Demi Moore portrayed naked while pregnant on a major magazine cover two decades before. Some of Ebony′s more conservative readers objected to the cover, stating it was inappropriate to feature an unwed, pregnant woman on the cover. The cover made national headlines in US Weekly and in a five-minute segment on CNN. More recent issues questioned whether President Obama was still right for black America and whether biracial Americans need more acknowledgment in today's society.

In May 2016, Johnson Publishing, the family business that founded Ebony and Jet, sold both publications to Texas-based private equity firm CVG Group for an undisclosed price.[21] Under CVG's ownership, Ebony struggled to find its footing, culminating in its 2017 move to lay off a third of its staff and move editorial operations to Los Angeles.[21]

In 2018, Ebony's publishing schedule was changed from being published monthly to a double issue published once each month.

On May 24, 2019, CVG suspended the print edition of the magazine, with the Spring 2019 issue the last to be printed.[22] Johnson Publishing filed for bankruptcy protections that same year.[23]

In December 2020, Milwaukee Bucks alum and Black businessman Junior Bridgeman bought Ebony and Jet for $14 million from CVG.[23] Under Bridgeman, the publication stated its intention to pivot toward themes of financial literacy and building Black wealth.[23]

In March 2021, the magazine relaunched in a digital format.[24][25]

In June 2024, it returned to Chicago for its Juneteenth celebration at Soho House.[26]

Notable coverage

[edit]100 Most Influential Blacks

[edit]One of the most famous aspects of the magazine was its list of "100 Most Influential Blacks". This list—which began in 1963, took a hiatus until 1971, and has continued on ever since—lists those who have made the greatest impact in the African-American community during the year. Most of those listed were well-educated, with 55 percent having completed a graduate degree.[27] However, some researchers have noted that black scholars, teachers, and higher-education administrators are rarely, if ever, included on the list.[28][29] The list exclusively focuses on entertainment figures, politicians, philanthropists, and entrepreneurs.[30]

The May 2001 "100+ Most Influential Black Americans" issue did not include a number of influential African Americans such as Thomas Sowell, Shelby Steele, Armstrong Williams, Walter Williams and, most notably, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. The Economist described the exclusion of Justice Thomas from the list as spiteful.[31]

Coolest Black Family in America

[edit]In 2018, the magazine published a series highlighting Black families from across the United States with the intention of showcasing Black family dynamics.[32]

25 Coolest Brothers of All Time

[edit]In August 2008, the magazine had published a special eight-cover edition featuring the "25 Coolest Brothers of All Time". The lineup featured popular figures like Jay-Z, Barack Obama, Prince, Samuel L. Jackson, Denzel Washington, Marvin Gaye, Muhammad Ali and Billy Dee Williams.[33]

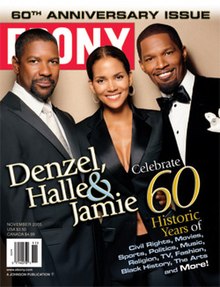

65th anniversary edition

[edit]In November 2010, the magazine featured a special 65th-anniversary edition cover featuring Taraji P. Henson, Samuel L. Jackson, Usher and Mary J. Blige. The issue included eight cover recreations from historic and iconic previous covers of Ebony. Blair Underwood posed inside, as did Omar Epps and Jurnee Smollett. National Public Radio marked this anniversary edition as the beginning of redesign of Ebony. Former White House social secretary Desiree Rogers, of the Obama administration, had become the chief executive officer of the magazine.[34]

Ownership

[edit]In 2016, Johnson Publishing Company sold the magazine along with Jet to private equity firm Clear View Group.[35][36][37] In May 2017, the editorial staff for the magazine moved from Chicago to Los Angeles along with the editorial staff for Jet magazine.[38] In December 2020, the magazine and its sister publication Jet[39] were purchased for $14 million by Junior Bridgeman.[40]

Ensuing financial difficulties

[edit]In July 2019, three months after Johnson Publishing Company filed for Chapter 7 Bankruptcy liquidation, it sold its historic photo archives including the prints and negatives to a consortium of foundations to be made available to the public.[41][42] After suspending the print edition of the magazine in May 2019, Clear View Group and Ebony Media Operations laid off the majority of the editing staff in June 2019.[43][44]

Lawsuits

[edit]In 2017, 50 freelance writers created a social media campaign #EbonyOwes due to not being paid by the magazines' current owner, Clear View Group. In response to the campaign, Clear View Group made an effort to pay 11 of the 50 writers $18,000, ending with only three being paid in full. In late 2017, the remaining writers with the help of The National Writers Union filed suit against Clear View Group and Ebony Media Operations.[22]

The remaining writers settled their lawsuit with the company in February 2018. The magazine owners were ordered to pay $80,000[45] Ebony Media Operations, Clear View Group and the National Writers Union agreed that all unpaid invoices would be paid over four quarterly installments by the end of 2018.[45] In October 2018, the magazines' owner missed its third quarter payment and another lawsuit was filed in November 2018. Clear View Group made the final payment to the writers in December 2018.[22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Circulation of select African American magazines in the United States in 2nd half 2015, by type(in thousands).Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Sharon Shahid (October 29, 2010). "65 Years Ago in News History: The Birth of Ebony Magazine". Newseum.org. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013.

- ^ Robert Channick (May 5, 2017). "Ebony cuts a third of its staff, moving editorial operations to LA". Chicagotribune.com. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ Barnett, Marlo; Flynn, Joseph E. (2014). "A Century of Celebration: Disrupting Stereotypes and Portrayals of African Americans in the Media". Black History Bulletin. 77 (2): 28–33. doi:10.1353/bhb.2014.0005. JSTOR 10.5323/blachistbull.77.2.0028. S2CID 245659860. Project MUSE 814089.

- ^ a b Krishnan, Satya P.; Durrah, Tracy; Winkler, Karen (July 1997). "Coverage of AIDS in Popular African American Magazines". Health Communication. 9 (3): 273–288. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc0903_5.

- ^ Wormley, J. Carlyne; Heinzerling, Barbara; Gunn, Virginia (1998). "Uncovering history: An examination of the impact of the Ebony Fashion Fair and Ebony magazine" (PDF). Consumer Interests Annual. 44: 148–150.

- ^ "From Negro Digest to Ebony, Jet and Em – Special Issue: 50 Years of JPC – Redefining the Black Image". Ebony. November 1992. Archived from the original on March 28, 2007.

- ^ EL'Zabar, Kai (June 16, 2016). "EBONY JET SOLD!". The Chicago Defender. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- ^ Ember, Sydney; Fandos, Nicholas (July 2, 2016). "Pillars of Black Media, Once Vibrant, Now Fighting for Survival". The New York Times.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (January 9, 2010). "Eunice Johnson Dies at 93; Gave Ebony Its Name". The New York Times.

- ^ Click, J.W. (December 1975). "Comparison of Editorial Content of Ebony Magazine, 1967 and 1974". Journalism Quarterly. 52 (4): 716–720. doi:10.1177/107769907505200416. S2CID 145071337.

- ^ "John H. Johnson | American publisher". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ "Ebony | American magazine". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Shipp, E. R. (December 6, 1985). "Ebony, 40, Viewed as More Than a Magazine". The New York Times.

- ^ West, James (July 2, 2016). "Power is 100 years old: Lerone Bennett Jr., Ebony magazine and the roots of black power". The Sixties. 9 (2): 165–188. doi:10.1080/17541328.2016.1241601. S2CID 151966947.

- ^ Glasrud, Bruce (September 18, 2007). "Ebony Magazine • BlackPast". BlackPast. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ Anderson, Mia L. (December 2015). "'I Dig You, Chocolate City': Ebony and Sepia Magazines' Coverage of Black Political Progress, 1971–1977". Journal of African American Studies. 19 (4): 398–409. doi:10.1007/s12111-015-9309-x. S2CID 152126803.

- ^ Staples, Brent (August 11, 2019). "The Radical Blackness of Ebony Magazine". The New York Times.

- ^ Pollay, Richard W.; Lee, Jung S.; Carter-Whitney, David (March 1992). "Separate, but Not Equal: Racial Segmentation in Cigarette Advertising". Journal of Advertising. 21 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1080/00913367.1992.10673359.

- ^ Dave Foulser (December 9, 2008). "Search and find magazines on Google Book Search". Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ a b "Ebony cuts a third of its staff, moving editorial operations to LA". Chicago Tribune. May 5, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c Yvonne de Salle, "Ebony Magazine In Flux – Print Magazine Folds, Digital Seems To Continue", Tin Shingle, July 8, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c Craig, Andrew (October 31, 2021). "Under new ownership, 'Ebony' magazine bets on boosting Black business". NPR. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ Business Insider, Eden Bridgeman Talks EBONY and JET relaunch, Interview, March 8, 2021

- ^ The Root, 'Rebirth of an Icon': Ebony Magazine Set to Digitally Relaunch Today, No Plans for Print Just Yet, March 1, 2021

- ^ Taylor, Savannah M. "EBONY RETURNS TO ITS CHICAGO ROOTS FOR A JUNETEENTH CELEBRATION AT SOHO HOUSE". Ebony. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Henry, Charles P. (1981). "Ebony Elite: America's Most Influential Blacks". Phylon. 42 (2): 120–132. doi:10.2307/274717. JSTOR 274717.

- ^ "Demeaning Stereotypes: Ebony's List of the Most Influential Black Americans". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (17): 46–47. 1997. doi:10.2307/2963216. JSTOR 2963216.

- ^ Cross, Theodore (1995). "Ebony Magazine: Sometimes The Bell Curve's Best Friend". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (10): 75–76. doi:10.2307/2962770. JSTOR 2962770.

- ^ "No Interest in Black Scholars: The Tweedledum and Tweedledee of African-American Publishing". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (37): 53–54. 2002. doi:10.2307/3134282. JSTOR 3134282.

- ^ "Lexington: The school of very hard knocks". The Economist. October 4, 2007. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ Dingle, Joycelyn (December 7, 2016). "The Coolest Black Family in America No. 74: The Coopers". Ebony. Retrieved December 7, 2016.

- ^ Sewing, Joy (July 9, 2008). "Ebony magazine honors the 'coolest' black men ever". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ Cheryl Corley, "'Ebony,' 'Jet' Parent Takes A Bold New Tack", NPR, September 22, 2011.

- ^ Channick, Robert. "Johnson Publishing sells Ebony, Jet magazines to Texas firm". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Ebony and Jet magazines have been sold – Northstar News Today". Northstar News Today. June 15, 2016. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Books, Ebony magazine's legendary photo archive is up for auction", LA Times, July 19, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Erick Johnson (Chicago Crusader/NNPA Member), "EBONY magazine moves to Los Angeles, Ebony Heads West, Leaves Chicago for Los Angeles", New York Amsterdam News, May 31, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ "This Millennial Bought Ebony and Jet For $14M, Plans to Bring the Magazines Into the Digital Era". August 11, 2021.

- ^ Cedric "Big Ced" Thorton (Black Enterprise), "Ebony Magazine Purchased by Former NBA Player Ulysses 'Junior' Bridgeman for $14 Million", Black Enterprise, December 23, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ "Rare look inside the Ebony and Jet magazine photo archive that just sold for $30M". CBS News. July 26, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ Noyes, Chandra (July 29, 2019). "Foundations Unite to Save Ebony Magazine Archives". artandobject.com. Journalistic, Inc. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ N'dea Yancey-Bragg, "Ebony magazine's digital staff abruptly laid off without pay as asset auction looms", USA Today, June 21, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Miana Massey, "Ebony and Jet magazines fire remainder of staff, may close, Legacy publications beset by financial issues", The Charlotte Post, July 7, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "Ebony to pay freelancers $80,000 to settle lawsuit after #EbonyOwes campaign", Chicago Tribune, February 27, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Back issues on Google Book Search

- Langston Hughes, "Publishing history of Ebony", Ebony, November 1965 (20th Anniversary Issue)

- "John H. Johnson's oral history – video excerpts", The National Visionary Leadership Project.

- Cheryl Corley, "Ebony, Jet Parent Takes A Bold New Tack", NPR, September 22, 2011.

- Nsenga Burton, "Ebony Jet Sells Headquarters Building", The Root, November 17, 2010.

- FBI file on Ebony