Laffer curve

| Part of a series on |

| Taxation |

|---|

|

| An aspect of fiscal policy |

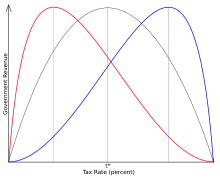

In economics, the Laffer curve illustrates a theoretical relationship between rates of taxation and the resulting levels of the government's tax revenue. The Laffer curve assumes that no tax revenue is raised at the extreme tax rates of 0% and 100%, meaning that there is a tax rate between 0% and 100% that maximizes government tax revenue.[a][1][2]

The shape of the curve is a function of taxable income elasticity—i.e., taxable income changes in response to changes in the rate of taxation. As popularized by supply-side economist Arthur Laffer, the curve is typically represented as a graph that starts at 0% tax with zero revenue, rises to a maximum rate of revenue at an intermediate rate of taxation, and then falls again to zero revenue at a 100% tax rate. However, the shape of the curve is uncertain and disputed among economists.[3]

One implication of the Laffer curve is that increasing tax rates beyond a certain point is counter-productive for raising further tax revenue. Particularly in the United States, conservatives have used the Laffer curve to argue that lower taxes may increase tax revenue. However, the hypothetical maximum revenue point of the Laffer curve for any given market cannot be observed directly and can only be estimated—such estimates are often controversial. According to The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, estimates of revenue-maximizing income tax rates have varied widely, with a mid-range of around 70%.[4] The shape of the Laffer curve may also differ between different global economies.[5]

The Laffer curve was popularized in the United States with policymakers following an afternoon meeting with Ford Administration officials Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld in 1974, in which Arthur Laffer reportedly sketched the curve on a napkin to illustrate his argument.[6] The term "Laffer curve" was coined by Jude Wanniski, who was also present at the meeting. The basic concept was not new; Laffer himself notes antecedents in the writings of the 14th-century social philosopher Ibn Khaldun and others.[7]

History

[edit]Ibn Khaldun, a 14th-century philosopher, wrote in his work The Muqaddimah: "It should be known that at the beginning of the dynasty, taxation yields a large revenue from small assessments. At the end of the dynasty, taxation yields a small revenue from large assessments."

Origin

[edit]Laffer states that he did not invent the concept, citing numerous antecedents, including the Muqaddimah by 14th-century Islamic scholar Ibn Khaldun,[7][8] John Maynard Keynes[7] and Adam Smith.[9] Andrew Mellon, Secretary of the Treasury from 1921 to 1932, articulated a similar policy idea in 1924.[10]

Laffer's name began to be associated with the idea after an article was published in National Affairs in 1978 that linked him to the idea.[9] In the National Affairs article, Jude Wanniski recalled a 1974 dinner meeting at the Two Continents Restaurant in the Washington Hotel with Arthur Laffer, Wanniski, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and his deputy press secretary Grace-Marie Arnett.[9][7] In this meeting, Laffer, arguing against President Gerald Ford's tax increase, reportedly sketched the curve on a napkin to illustrate the concept.[6] Cheney did not accept the idea immediately, but it caught the imaginations of those present.[11] Laffer professes no recollection of this napkin, but writes: "I used the so-called Laffer Curve all the time in my classes and with anyone else who would listen to me".[7]

Precedents

[edit]

There are historical precedents other than those cited by Laffer. Ferdinando Galiani wrote in Della Moneta (1751) that "It is an enormous error ... to believe that an impost always yields more revenue as it becomes heavier".[12] He gave the example of a toll on late-night entry to a town which would be less remunerative if set unreasonably high. David Hume expressed similar arguments in his essay Of Taxes in 1756, as did fellow Scottish economist Adam Smith twenty years later.[13]

At the time of the Irish famine of the mid-1840s, Edward Twisleton suggested that lower local taxes in Ireland would increase the amount of taxes successfully collected towards relief. An analysis of actual collection rates has indicated that areas with higher rates did collect a lesser proportion of the tax due.[14]

The Democratic party embraced this argument in the 1880s when high revenue from import tariffs raised during the Civil War (1861–1865) led to federal budget surpluses. The Republican party, which was then based in the protectionist industrial Northeast, argued that cutting rates would lower revenues.

In 1924, Secretary of Treasury Andrew Mellon wrote: "It seems difficult for some to understand that high rates of taxation do not necessarily mean large revenue to the government, and that more revenue may often be obtained by lower rates". Exercising his understanding that "73% of nothing is nothing", he pushed for the reduction of the top income tax bracket from 73% to an eventual 24% (as well as tax breaks for lower brackets). Mellon was one of the wealthiest people in the United States, the third-highest income-tax payer in the mid-1920s, behind John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford.[15] While he served as Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Department his wealth peaked at around US$300–400 million. Personal income tax receipts rose from US$719 million in 1921 to over US$1 billion in 1929, an average increase of 4.2% per year over an 8-year period, which supporters attribute to the rate cut.[16]

In 2012, economists surveyed by the University of Chicago rejected the viewpoint that the Laffer curve's postulation of increased tax revenue through a rate cut applies to federal US income taxes of the time in the medium term. When asked whether a "cut in federal income tax rates in the US right now would raise taxable income enough so that the annual total tax revenue would be higher within five years than without the tax cut", none of the economists surveyed agreed and 71% disagreed.[17] According to Harvard University economist Jeffrey Frankel, a substantial majority of economists reject the proposition that income taxes are so high in the United States that tax cuts will pay for themselves.[18]

Empirical analysis

[edit]One of the conceptual uses of the Laffer curve is to determine the rate of taxation that will raise the maximum revenue (in other words, "optimizing" revenue collection). The revenue maximizing tax rate should not be confused with the optimal tax rate, which economists use to describe tax rates in a tax system that raises a given amount of revenue with the fewest distortions to the economy.[19]

In 2017, Jacob Lundberg of the Uppsala University estimated Laffer curves for 27 OECD countries, with top income-tax rates maximising tax revenue ranging from 60 to 61% (Austria, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Sweden) to 74–76% (Germany, Switzerland, UK, US). Most countries appear to have set their highest tax rates below the peak rate, while five countries are exceeding it (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Sweden).[20]

Writing in 2010, John Quiggin said, "To the extent that there was an economic response to the Reagan tax cuts, and to those of George W. Bush twenty years later, it seems largely to have been a Keynesian demand-side response, to be expected when governments provide households with additional net income in the context of a depressed economy."[21] A 1999 study by University of Chicago economist Austan Goolsbee, which examined major changes in high income tax rates in the United States from the 1920s onwards found no evidence that the United States was to the right of the peak of the Laffer curve.[22]

Income tax rate at which revenue is maximized

[edit]

In the early 1980s, Edgar L. Feige and Robert T. McGee developed a macroeconomic model from which they derived a Laffer curve. According to the model, the shape and position of the Laffer curve depend upon the strength of supply side effects, the progressivity of the tax system and the size of the unobserved economy.[24][25][26] Economist Paul Pecorino presented a model in 1995 that predicted the peak of the Laffer curve occurred at tax rates around 65%.[27] A draft paper by Y. Hsing looking at the United States economy between 1959 and 1991 placed the revenue-maximizing average federal tax rate between 32.67% and 35.21%.[28] A 1981 article published in the Journal of Political Economy presented a model integrating empirical data that indicated that the point of maximum tax revenue in Sweden in the 1970s would have been 70%.[29] A 2011 study by Trabandt and Uhlig published in the Journal of Monetary Economics estimated a 70% revenue maximizing rate, and estimated that the US and most European economies were on the left of the Laffer curve (in other words, that raising taxes would raise further revenue).[23] A 2005 study concluded that with the exception of Sweden, no major OECD country could increase revenue by reducing the marginal tax rate.[30]

The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics reports that a comparison of academic studies yields a range of revenue maximizing rates that centers around 70%.[4]

Taxation of goods and services

[edit]

The Laffer curve has also been extended to taxation of goods and services. In their 2018 Econometrica paper, Miravete, Seim, and Thurk, show that in non-competitive markets, the strategic pricing response of firms is important to consider when estimating the Laffer curve.[31] The authors show that firms increase their prices in response to a decrease in the ad valorem tax, leading to less of a quantity increase than would otherwise be expected. The net effect is to flatten the Laffer curve and move the revenue maximum point to the right.

Congressional Budget Office analysis

[edit]In 2005, the United States Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released a paper called "Analyzing the Economic and Budgetary Effects of a 10 Percent Cut in Income Tax Rates." This paper considered the impact of a stylized reduction of 10% in the then existing marginal rate of federal income tax in the US (for example, if those facing a 25% marginal federal income tax rate had it lowered to 22.5%). Unlike earlier research, the CBO paper estimates the budgetary impact of possible macroeconomic effects of tax policies, that is, it attempts to account for how reductions in individual income tax rates might affect the overall future growth of the economy, and therefore influence future government tax revenues; and ultimately, impact deficits or surpluses. In the paper's most generous estimated growth scenario, only 28% of the projected lost revenue from the lower tax rate would be recouped over a 10-year period after a 10% across-the-board reduction in all individual income tax rates. In other words, deficits would increase by nearly the same amount as the tax cut in the first five years, with limited feedback revenue thereafter. Through increased budget deficits, the tax cuts primarily benefiting the wealthy will be paid for—plus interest—by taxes borne relatively evenly by all taxpayers.[32] The paper points out that these projected shortfalls in revenue would have to be made up by federal borrowing: the paper estimates that the federal government would pay an extra US$200 billion in interest over the decade covered by the paper's analysis.[33][34] In 2019, economists at the Joint Committee on Taxation revisited the macroeconomic and budgetary response to the stylized 10% reduction in statutory ordinary income tax rates, but from the levels set by P.L. 115-97.[35] While incorporating additional tax detail within the modeling framework relative to previous analyses, the paper similarly estimates that this policy change would result in increased budget deficits - both in the short- and long-run - after accounting for revenue feedback from macroeconomic changes.

United Kingdom

[edit]Following the reduction of the top rate of income tax in the UK from 50% to 45% in 2013, HMRC estimated the cost of the tax reduction to be about £100 million (out of an income for this group of around £90 billion), but with large uncertainty on both sides. Robert Chote, the chairman of the UK Office for Budget Responsibility commented that Britain was "strolling across the summit of the Laffer curve", implying that UK tax rates had been close to the optimum rate.[36][37]

Other

[edit]Laffer has presented the examples of Russia and the Baltic states, which instituted a flat tax with rates lower than 35% around the same time that their economies started growing. He has similarly referred to the economic outcome of the Kemp-Roth tax cuts, the Kennedy tax cuts, the 1920s tax cuts, and the changes in US capital gains tax structure in 1997.[7] Some have also cited Hauser's Law, which postulates that US federal revenues, as a percentage of GDP, have remained stable at approximately 19.5% over the period 1950 to 2007 despite changes in marginal tax rates over the same period.[38] Others however, have called Hauser's Law "misleading" and contend that tax changes have had large effects on tax revenues.[39]

More recently, based on Laffer curve arguments, Kansas Governor Sam Brownback greatly reduced state tax rates in 2012 in what has been called the Kansas experiment.[40][41][42] Laffer was paid $75,000 to advise in the creation of Brownback's tax cut plan, and gave Brownback his full endorsement, stating that what Brownback was doing was "truly revolutionary."[40] The state, which had previously had a budget surplus, experienced a budget deficit of about $200 million in 2012. Drastic cuts to state funding for education and infrastructure followed[43] before the tax cut was repealed in 2017 by a bipartisan super majority in the Kansas legislature.[40]

In US political discourse

[edit]Supply-side economics rose in popularity among Republican Party politicians from 1977 onwards. Prior to 1977, Republicans were more split on tax reduction, with some worrying that tax cuts would fuel inflation and exacerbate deficits.[44]

Use in supply-side economics

[edit]Supply-side economics is a school of macroeconomic thought that argues that overall economic well-being is maximized by lowering the barriers to producing goods and services (the "Supply Side" of the economy). By lowering such barriers, consumers are thought to benefit from a greater supply of goods and services at lower prices. Typical supply-side policy would advocate generally lower income tax and capital gains tax rates (to increase the supply of labor and capital), smaller government and a lower regulatory burden on enterprises (to lower costs). Although tax policy is often mentioned in relation to supply-side economics, supply-side economists are concerned with all impediments to the supply of goods and services and not just taxation.[45]

In their economics textbook Principles of Economics (7th edition), economists Karl E. Case of Wellesley College and Ray Fair of Yale University state "The Laffer curve shows the relationship between tax rates and tax revenues. Supply-side economists use it to argue that it is possible to generate higher revenues by cutting tax rates, but evidence does not appear to support this."[46][26]

Reaganomics

[edit]The Laffer curve and supply-side economics inspired Reaganomics and the Kemp-Roth Tax Cut of 1981. Supply-side advocates of tax cuts claimed that lower tax rates would generate more tax revenue because the United States government's marginal income tax rates prior to the legislation were on the right-hand side of the curve. This assertion was derided by George H. W. Bush as "voodoo economics" while running against Reagan for the Presidential nomination in 1980.[47] During the Reagan presidency, the top marginal rate of tax in the United States fell from 70% to 28%.

David Stockman, Ronald Reagan's budget director during his first administration and one of the early proponents of supply-side economics, was concerned that the administration did not pay enough attention to cutting government spending. He maintained that the Laffer curve was not to be taken literally—at least not in the economic environment of the 1980s United States. In The Triumph of Politics, he writes: "[T]he whole California gang had taken [the Laffer curve] literally (and primitively). The way they talked, they seemed to expect that once the supply-side tax cut was in effect, additional revenue would start to fall, manna-like, from the heavens. Since January, I had been explaining that there is no literal Laffer curve."[48] Stockman also said that "Laffer wasn't wrong, he just didn't go far enough" (in paying attention to government spending).[49]

Some have criticized elements of Reaganomics on the basis of equity. For example, economist John Kenneth Galbraith believed that the Reagan administration actively used the Laffer curve "to lower taxes on the affluent".[50] Some critics point out that tax revenues almost always rise every year, and during Reagan's two terms increases in tax revenue were more shallow than increases during presidencies where top marginal tax rates were higher.[51] Critics also point out that since the Reagan tax cuts, income has not significantly increased for the rest of the population. This assertion is supported by studies that show the income of the top 1% nearly doubling during the Reagan years, while income for other income levels increased only marginally; income actually decreased for the bottom quintile.[52] However, a 2018 study by the Congressional Budget Office showed average household income rising 68.8% for the bottom quintile after government transfers (in the form of various income support and in-kind programmes, subsidies, and taxes) from 1979 to 2014. This same study showed the middle quintile's income rising 41.5% after government transfers and taxes.[53]

Bush tax cuts

[edit]The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that extending the Bush tax cuts of 2001–2003 beyond their 2010 expiration would increase deficits by $1.8 trillion over the following decade.[54] Economist Paul Krugman contended that supply-side adherents did not fully believe that the United States income tax rate was on the "backwards-sloping" side of the curve and yet they still advocated lowering taxes to encourage investment of personal savings.[55]

Theoretical issues

[edit]Justifications

[edit]Supply-side economics indicates that the simple descriptions of the Laffer curve are usually intended for pedagogical purposes only and do not represent the complex economic responses to tax policy which may be observed from such viewpoints as provided by supply-side economics. Although the simplified Laffer curve is usually illustrated as a straightforward symmetrical and continuous bell-shaped curve, in reality the bell-shaped curve may be skewed or lop-sided to either side of the 'maximum'. Within the reality of complex and sudden changes to tax policy over time, the response of tax revenue to tax rates may vary dramatically and is not necessarily even continuous over time, when for example new legislation is enacted which abruptly changes tax revenue expectations.[56][57]

The simplified static Laffer curve

[edit]

Laffer explains the model in terms of two interacting effects of taxation: an "arithmetic effect" and an "economic effect".[7] The "arithmetic effect" assumes that tax revenue raised is the tax rate multiplied by the revenue available for taxation (or tax base). Thus revenue R is equal to t × B where t is the tax rate and B is the taxable base (R = t × B). At a 0% tax rate, the model states that no tax revenue is raised. The "economic effect" assumes that the tax rate will affect the tax base itself. At the extreme of a 100% tax rate, the government collects zero revenue because taxpayers change their behavior in response to the tax rate: either they lose their incentive to work, or they find a way to avoid paying taxes. Thus, the "economic effect" of a 100% tax rate is to decrease the tax base to zero. If this is the case, then somewhere between 0% and 100% lies a tax rate that will maximize revenue.

Graphical representations of the curve sometimes appear to put the rate at around 50%, if the tax base reacts to the tax rate linearly, but the revenue-maximizing rate could theoretically be any percentage greater than 0% and less than 100%. Similarly, the curve is often presented as a parabolic shape, but there is no reason that this is necessarily the case. The effect of changes in tax can be cased in terms of elasticities, where the revenue-maximizing elasticity of the tax base with respect to the tax is equal to 1. This is done by differentiating R with respect to t and grouping terms to reveal that the rate of change of R with respect to t is equal to the sum of elasticity of the tax base plus one all multiplied by the tax base. Thus as elasticity surpasses one absolute value, revenues begin to fall. The problem is similar to that of the monopolist who must never increase prices beyond the point at which the elasticity of demand exceeds one in absolute value.

Wanniski noted that all economic activity would be unlikely to cease at 100% taxation, but it would switch from the exchange of money to barter. He also noted that there can be special circumstances in which economic activity can continue for a period at a near 100% taxation rate (for example, in war economy).[13]

Various efforts have been made to quantify the relationship between tax revenue and tax rates (for example, in the United States by the Congressional Budget Office).[33] While the interaction between tax rates and tax revenue is generally accepted, the precise nature of this interaction is debated. In practice, the shape of a hypothetical Laffer curve for a given economy can only be estimated. The relationship between tax rate and tax revenue is likely to vary from one economy to another and depends on the elasticity of supply for labor, as well as various other factors. Even in the same economy, the characteristics of the curve could vary over time. Complexities such as progressive taxes and possible differences in the incentive to work for different income groups complicate the task of estimation. The structure of the curve may also be changed by policy decisions. For example, if tax loopholes and tax shelters are made more readily available by legislation, the point at which revenue begins to decrease with increased taxation is likely to become lower.

Laffer presented the curve as a pedagogical device to show that in some circumstances, a reduction in tax rates will actually increase government revenue and not need to be offset by decreased government spending or increased borrowing. For a reduction in tax rates to increase revenue, the current tax rate would need to be higher than the revenue maximizing rate. In 2007, Laffer said that the curve should not be the sole basis for raising or lowering taxes.[58]

The supply-side dynamic Laffer curve

[edit]Supply-siders argue that in a high tax rate environment, lowering tax rates would result in either increased revenues or smaller revenue losses than one would expect relying on only static estimates of the previous tax base.[59][60]

This led supply-siders to advocate large reductions in marginal income and capital gains tax rates to encourage greater investment, which would produce more supply. Jude Wanniski and many others advocate a zero capital gains rate.[56][61] The increased aggregate supply would result in increased aggregate demand, hence the term "supply-side economics".

Criticisms

[edit]Laffer assumes that the government's revenue is a continuous function of the tax rate. However, in some theoretical models, the Laffer curve can be discontinuous, leading to an inability to devise a revenue-maximizing tax rate solution.[62] Additionally, the Laffer curve depends on the assumption that tax revenue is used to provide a public good that is separable in utility and separate from labor supply, which may not be true in practice.[63]

The Laffer curve as presented is simplistic in that it assumes a single tax rate and a single labor supply. Actual systems of public finance are more complex, and there is serious doubt about the relevance of considering a single marginal tax rate.[4] In addition, revenue may well be a multivalued function of tax rate; for instance, an increase in tax rate to a certain percentage may not result in the same revenue as a decrease in tax rate to the same percentage (a kind of hysteresis). Furthermore, the Laffer curve does not take explicitly into account the nature of the tax avoidance taking place. It is possible that if all producers are endowed with two survival factors in the market (ability to produce efficiently and ability to avoid tax), then the revenues raised under tax avoidance can be greater than without avoidance, and thus the Laffer curve maximum is found to be farther right than thought. The reason for this result is that if producers with low productive abilities (high production costs) tend to have strong avoidance abilities as well, a uniform tax on producers actually becomes a tax that discriminates on the ability to pay. However, if avoidance abilities and productive abilities are unrelated, then this result disappears.[64]

Generally, among other criticisms, the Laffer curve has been scrutinised as intangible and inapplicable in the real world, i. e. in a real national economy. On the contrary, diligent application of the Laffer curve in the past has actually led to controversial outcomes. Since its proposal, there have been several real-life trials of modelling the Laffer curve and its consequent application, which have resulted in the finding that tax rates, which are actually utilised by the governing body, are to the left of the Laffer curve turning point, which would maximise tax revenue. More significantly, the result of several experiments, which tried to adjust the tax rate to the one proposed by the Laffer curve model, resulted in a significant decrease in national tax revenue - lowering the economy's tax rate led to an increase in the government budget deficit. The occurrence of this phenomenon is most famously attributed to the Reagan administration (1981–1989), during which the government deficit increased by approx. $2 trillion.[65]

See also

[edit]- Deadweight loss

- Dynamic scoring

- Fiscal conservatism

- List of economics topics

- Rahn curve

- Trickle-down economics

Notes

[edit]- ^ Under the assumption that the revenue is a continuous function of the rate of taxation, the extreme value theorem states that a maximum must exist.

References

[edit]- ^ L.H. Meyer (December 6, 2012). The Supply-Side Effects of Economic Policy. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 83. ISBN 978-94-009-8174-4.

- ^ Gahvari, Firouz (1989). "The nature of government expenditures and the shape of the laffer curve". Journal of Public Economics. 40 (2): 251–260. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(89)90006-6. ISSN 0047-2727.

- ^ Irvin B. Tucker (2010), Survey of Economics, Cengage Learning, p. 341, ISBN 978-1-4390-4054-6

- ^ a b c Fullerton, Don (2008). "Laffer curve". In Durlauf, Steven N.; Blume, Lawrence E. (eds.). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (2nd ed.). p. 839. doi:10.1057/9780230226203.0922. ISBN 978-0-333-78676-5.

- ^ Trabandt, Mathias; Uhlig, Harald (May 1, 2011). "The Laffer curve revisited". Journal of Monetary Economics. 58 (4): 305–327. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2011.07.003. ISSN 0304-3932.

- ^ a b "To Donald Rumsfeld". Polyconomics.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Laffer, Arthur. "The Laffer Curve: Past, Present, and Future". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2024.

- ^ Brederode, Robert F. van (2009). Systems of general sales taxation : theory, policy and practice. Austin [Tex.]: Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. p. 117. ISBN 978-9041128324.

- ^ a b c Shiller, Robert J. (2017). "Narrative Economics". American Economic Review. 107 (4): 967–1004. doi:10.1257/aer.107.4.967. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ "Trump is giving Arthur Laffer the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Economists aren't smiling". The Washington Post. 2019.

- ^ Gellman, Barton, 258. Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency, Penguin Press, New York 2008.

- ^ Italian: "È errore grandissimo ... credere che un dazio frutifichi sempre più se più s'aggrava." p. 193 of the 1916 reprint.

- ^ a b Wanniski, Jude (1978). "Taxes, Revenues and the 'Laffer Curve'" (PDF). The Public Interest. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ Read, Charles (2022). The Great Famine in Ireland and Britain's financial crisis. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 193–196. ISBN 978-1-80010-627-7. OCLC 1365041253.

- ^ Cannadine, David. Mellon: An American Life. New York: A. A. Knopf, 2006. pp. 48–49, 165, 349. ISBN 0-679-45032-7.

- ^ Folsom Jr., Burton W., The Myth of the Robber Barons, p. 103. Young America's Foundation, 2007.

- ^ "Poll Results". IGM Forum.

- ^ Frankel, Jeffrey (2011). "A Lesson from the South for Fiscal Policy in the US and Other Advanced Countries". Comparative Economic Studies. 53 (3): 407–430. doi:10.1057/ces.2011.7. ISSN 0888-7233.

- ^ Seth A., Giertz (May 30, 2008). How Does the Elasticity of Taxable Income Affect Economic Efficiency and Tax Revenues and what Implications Does this have for Tax Policy Moving Forward? (PDF). Conference on Tax Policy Lessons from the 2000s. American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research. pp. 36–42. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ Jacob Lundberg (August 31, 2017). "The Laffer curve for high incomes" (PDF). Luxembourg Income Study.

- ^ Quiggin, John (May 21, 2012). Zombie Economics. Princeton University Press. p. 142. doi:10.2307/j.ctt7rg7m. ISBN 978-1-4008-4208-7.

- ^ Goolsbee, Austan (1999). "Evidence on the High-Income Laffer Curve from Six Decades of Tax Reform" (PDF). Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 1999 (2): 1–64. doi:10.2307/2534678. ISSN 0007-2303. JSTOR 2534678.

- ^ a b Trabandt, Mathias; Uhlig, Harald (2011). "The Laffer Curve Revisited". Journal of Monetary Economics. 58 (4): 305–327. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2011.07.003.

- ^ Feige, Edgar L.; McGee, Robert (1982). "Supply Side Economics and the Unobserved Economy: The Dutch Laffer Curve". Economisch Statistische Berichten. 67 (November).

- ^ Feige, Edgar L.; McGee, Robert (1982). "The Unobserved Economy and the UK Laffer Curve". The Journal of Economic Affairs. 3 (1): 36–42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0270.1982.tb01459.x.

- ^ a b Feige, Edgar L.; McGee, Robert (1983). "Sweden's Laffer Curve:Taxation and the Unobserved Economy" (PDF). The Scandinavian Journal of Economics. 85 (4): 499–519. doi:10.2307/3439948. hdl:10419/94771. JSTOR 3439948. S2CID 12592215.

- ^ Pecorino, Paul (1995). "Tax rates and tax revenues in a model of growth through human capital accumulation". Journal of Monetary Economics. 36 (3): 527. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(95)01224-9.

- ^ Hsing, Y. (1996). "Estimating the Laffer Curve and Policy Implications". Journal of Socio-Economics. 25 (3): 395. doi:10.1016/S1053-5357(96)90013-X.

- ^ Stuart, C. E. (1981). "Swedish Tax Rates, Labor Supply, and Tax Revenues". Journal of Political Economy. 89 (5): 1020–38. doi:10.1086/261018. JSTOR 1830818. S2CID 153840972.

- ^ Heijman, W. J. M.; van Ophem, J. A. C. (2005). "Willingness to pay tax: The Laffer curve revisited for 12 OECD countries". The Journal of Socio-Economics. 34 (5): 714–723. doi:10.1016/j.socec.2005.07.013. ISSN 1053-5357.

- ^ Miravete, Eugenio J.; Seimb, Katja; Thurk, Jeff (September 2018). "Market Power and the Laffer Curve". Econometrica. 86 (5): 1651–1687. doi:10.3982/ECTA12307. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Analyzing the Economic and Budgetary Effects of a 10 Percent Cut in Income Tax Rates" (PDF). December 1, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 12, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2006.

- ^ a b "CBO. (December 1, 2005). Analyzing the Economic and Budgetary Effects of a 10 Percent Cut in Income Tax Rates" (PDF). Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ Romer, Christina D; Romer, David H (June 1, 2010). "The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks". American Economic Review. 100 (3): 763–801. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.715.612. doi:10.1257/aer.100.3.763. S2CID 16550557.

- ^ Moore, Rachel; Pecoraro, Brandon (2020). "Macroeconomic Implications of Modeling the Internal Revenue Code in a Heterogeneous-Agent Framework". Economic Modelling. 87. Economic Modeling: 72–91. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2019.07.007. S2CID 59353161.

- ^ Chu, Ben (April 8, 2014). "Only time will tell if income tax changes prove worthwhile". The Independent. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Maugham, Jolyon (March 1, 2016). "How George Osborne's policies have lost the country £2.4bn in tax". The Independent. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Ranson, David (Fall 2008). "Hauser's Law". Hoover Digest (4). Archived from the original on January 8, 2010.

- ^ Kimmel, Mike (November 30, 2010). "Hauser's Law is Extremely Misleading". Angry Bear. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c Alvord, Daniel R. (March 1, 2020). "What Matters to Kansas: Small Business and the Defeat of the Kansas Tax Experiment". Politics & Society. 48 (1): 27–66. doi:10.1177/0032329219894788. ISSN 0032-3292.

- ^ Shields, Mike (August 14, 2012). "The brain behind the Brownback tax cuts". Kansas Health Institute. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Topeka Capital Journal, 2013

- ^ Kansas City Star, 2015

- ^ Burns, John W.; Taylor, Andrew J. (2000). "The Mythical Causes of the Republican Supply-Side Economics Revolution". Party Politics. 6 (4): 419–440. doi:10.1177/1354068800006004002. ISSN 1354-0688. S2CID 144473289.

- ^ "Supply-Side Economics and Austrian Economics". April 1987.

- ^ Feige, Edgar; McGee, Robert (1982). "Supply Side Economics and the Unobserved Economy: The Dutch Laffer Curve". Economisch Statistische Berichten. 67 (November).

- ^ "Reagonomics or 'voodoo economics'?". BBC News. June 5, 2004. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Stockman, David (March 26, 2013). The Triumph of Politics: Why the Reagan Revolution Failed. PublicAffairs. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-61039-277-8.

- ^ "The Education of David Stockman". The Atlantic. December 1981.

- ^ Galbraith, J. K. (Sinclair-Stevenson 1994). The World Economy Since The Wars. A Personal View, p. 232.

- ^ "Tax cuts increase tax collections".

- ^ "Cumulative Growth In Average After-Tax Income, By Income Group; graph, p. 19" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. October 2011.

- ^ "Cumulative Growth in Average Income, by Income Group, 1979 to 2014". Congressional Budget Office. March 2018.

- ^ "An Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals for Fiscal Year 2008" (PDF). March 21, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ Peddling Prosperity by Paul Krugman, p. 95

- ^ a b Wanniski, Jude "Taxing Capital Gains" Archived 2014-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alan Reynolds (July 1999). "Capital gains tax: Analysis of reform options for Australia" (PDF). Hudson Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2005.

- ^ Fox, Justin (December 6, 2007). "Tax Cuts Don't Boost Revenues". Time. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Laffer, Arthur (June 1, 2004). "The Laffer Curve, Past, Present and Future". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on December 1, 2007. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ Bartlett, Bruce (April 6, 2007). "How Supply-Side Economics Trickled Down". New York Times.

- ^ Alan Reynolds (July 1999). "Capital gains tax: Analysis of reform options for Australia" (PDF). Hudson Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2005.

- ^ Malcomson, J (1986). "Some analytics of the laffer curve". Journal of Public Economics. 29 (3): 263. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(86)90029-0.

- ^ Gahvari, F (1989). "The nature of government expenditures and the shape of the laffer curve". Journal of Public Economics. 40 (2): 251. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(89)90006-6.

- ^ Palda, Filip (1998). "Evasive Ability and the Efficiency Cost of the Underground Economy". Canadian Journal of Economics. 31 (5): 1118–38. doi:10.2307/136462. JSTOR 136462.

- ^ Morgan, Jamie (February 17, 2021). "A critique of the Laffer theorem's macro-narrative consequences for corporate tax avoidance from a Global Wealth Chain perspective". Globalizations. 18 (2): 174–194. Bibcode:2021Glob...18..174M. doi:10.1080/14747731.2020.1760420. ISSN 1474-7731.