Tapejaridae

| Tapejarids Temporal range: Early to Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

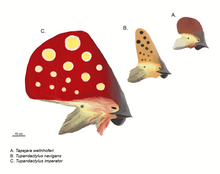

| Collection of various tapejarid skulls to scale with one another. From left to right, top to bottom:

Torukjara bandeirae, Caiuajara dobruskii, Tupandactylus imperator, Tapejara wellnhoferi, Huaxiadraco corollatus, and Sinopterus dongi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Tapejaromorpha |

| Family: | †Tapejaridae Kellner, 1989 |

| Type species | |

| †Tapejara wellnhoferi Kellner, 1989

| |

| Genera | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Tapejaridae (from a Tupi word meaning "the lord of the ways") is a family of azhdarchoid pterosaurs from the Cretaceous period. Members are currently known from Brazil, England, Hungary, Morocco,[1] Spain,[2] the United States,[3] and China. The most primitive genera were found in China, indicating that the family has an Asian origin.[4]

Description

[edit]

Tapejarids were small to medium-sized pterosaurs with several unique, shared characteristics, mainly relating to the skull. Most tapejarids possessed a bony crest arising from the snout (formed mostly by the premaxillary bones of the upper jaw tip). In some species, this bony crest is known to have supported an even larger crest of softer, fibrous tissue that extends back along the skull. Tapejarids are also characterized by their large nasoantorbital fenestra, the main opening in the skull in front of the eyes, which spans at least half the length of the entire skull in this family. Their eye sockets were small and pear-shaped.[5] Studies of tapejarid brain cases show that they had extremely good vision, more so than in other pterosaur groups, and probably relied nearly exclusively on vision when hunting or interacting with other members of their species.[6] Tapejarids had unusually reduced shoulder girdles that would have been slung low on the torso, resulting in wings that protruded from near the belly rather than near the back, a "bottom decker" arrangement reminiscent of some planes.[6]

Biology

[edit]Tapejarids appear to have been arboreal, having more curved claws than other azhdarchoid pterosaurs and occurring more commonly in fossil sites with other arboreal flying vertebrates such as early birds. Tapejarids have long been speculated as having been frugivores or omnivores, based on their parrot-like beaks.[7] Direct evidence for plant-eating is known in a specimen of Sinopterus that preserves seeds in the abdominal cavity. The Barremian- Aptian distribution of some tapejarids may even be partially associated with the first radiation phase of the angiosperms, especially of the genus Klitzschophyllites which represents a more basal angiosperm.[8][9]

Classification

[edit]

Tapejaridae was named and defined by Brazilian paleontologist Alexander Kellner in 1989 as the clade containing both Tapejara and Tupuxuara, plus all descendants of their most recent common ancestor. In 2007, Kellner divided the family: Tapejarinae, consisting of Tapejara and its close relatives, and Thalassodrominae, consisting of Thalassodromeus and Tupuxuara.[10] A 2011 subsumed the family Chaoyangopterinae in as the subfamily Chaoyangopterinae,[5] something not followed by future authors. Kellner's concept of a Tapejaridae consisting of Tapejarinae and Thalassodrominae would be the basis for numerous subsequent phylogenetic analyses.[11][12][13][14][15]

Various opposing studies have arose challenging Kellner's concept of Tapejaridae. The 2003 model of paleontologist David Unwin found Tupuxara and Thalassodromeus to be more distantly related to Tapejara and therefore outside of Tapejaridae, instead being related to Azhdarchidae.[16] Later, in 2006, British paleontologists David Martill and Darren Naish followed Unwin's concept, and provided a revised definition for Tapejaridae was also proposed: the clade containing all species more closely related to Tapejara than to Quetzalcoatlus.[17] A 2008 study by Lü Junchang and colleagues also corroborated this model, and used the term "Tupuxuaridae" to include both genera.[18] In 2009, British paleontologist Mark Witton also agreed with the Unwin model. However, he noted that the term Thalassodrominae was created before Tupuxuaridae, meaning it had naming priority. He elevated Thalassodrominae to family level, thus creating the denomination Thalassodromidae.[19]

Regarding the core tapejarid clade, American paleontologist Brian Andres and colleagues formally defined Tapejaridae as the clade containing Tapejara and Sinopterus in 2014. They also re-defined the subfamily Tapejarinae as all species closer to Tapejara than to Sinopterus, and added a new clade, Tapejarini, to include all descendants of the last common ancestor of Tapejara and Tupandactylus.[20] In 2020, in the description of the genus Wightia, an opposing subfamily was named, Sinopterinae, consisting of tapejarids more closely related to Sinopterus than Tapejara.[21] These studies follow the Unwin model, opposing Kellner's model of Tapejaridae while corroborating the close relationship between thalassodromids, azhdarchids, rather than tapejarids.

In 2023, paleontologist Rodrigo Pêgas and colleagues argued that despite the disagreements about the position of Thalassodromeus and its relatives, the species in question were consistently related. Therefore, they favored the term Thalassodromidae to have consistency with other studies that used the same name, despite finding them to form a natural grouping with Tapejaridae in their phylogenetic analysis (per the Kellner model). Thus, Thalassodromidae and Tapejaridae would be separate families within Tapejaromorpha.In their 2023 study, Pêgas and colleagues redefined Tapejaridae to be the most recent common ancestor of Sinopterus, Tapejara, and Caupedactylus in order to preserve the scope of the family in light of finding Caupedactylus, traditionally a tapejarine, outside of the Andres definition of Tapejaridae. They divided this redefined Tapejaridae into the groups Eutapejaria, containing the subfamilies Sinopterinae and Tapejarinae, and Caupedactylia, containing the pterosaurs Caupedactylus and Aymberedactylus.[22] In 2024, Pêgas rejected this redefinition of Tapejaridae in light of non-compliance with phylocode rules, applying the Tapejara and Sinopterus definition and deeming Eutapejaria a synonym. Instead, he created the larger group contain Tapejaridae and Caupedactylia, removing Caupedactylus and Aymberedactylus from the family itself.[23]

The cladogram below shows the phylogenetic analysis conducted by paleontologist Gabriela Cerqueira and colleagues in 2021, which uses Kellner's nomenclature of Tapejaridae.[24]

| Tapejaridae |

| ||||||

Below are two cladograms representing different concepts of Tapejaridae. The first one shows the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Andres in 2021, in which Tapejaridae consists of the subfamilies Tapejarinae and Sinopterinae. He found the pterosaurs Lacusovagus and Keresdrakon as tapejarines, an arrangement that had never been recovered in previous analyses. Regarding the interrelationships of Tapejaridae, Andres follows Unwin's concept.[25] The second cladogram shows the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Pêgas in 2024. He also found Tapejaridae to consist of both Tapejarinae and Sinopterinae, but differed from Andres in recovering the tapejarid Bakonydraco as a sinopterine instead of tapejarine. He created the new subtribe Caiuajarina within Tapejarini to include Caiuajara and Torukjara. Additionally, his analysis further differs from that of Andres in finding both Tapejaridae and Thalassodromidae within Tapejaromorpha, which corroborates the close relationship between thalassodromids and tapejarids, similar to Kellner.[23]

|

Topology 1: Andres (2021).

|

Topology 2: Pêgas (2024).

|

Subclades

[edit]Summary of the phylogenetic definitons of tapejarid subclades as discussed in the classification section.

| Name | Named by | Definition | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caiuajarina | Pêgas, 2024[26] | The largest clade containing Caiuajara dobruskii, but not Tapejara wellnhoferi. | |

| Caupedactylia | Pêgas et al., 2023[22] | The largest clade containing Caupedactylus ybaka, but not Tapejara wellnhoferi. | May be within Tapejaridae or just outside in the broader clade Tapejariformes. |

| Eutapejaria | Pêgas et al., 2023[22] | The largest clade containing Tapejara wellnhoferi, but not Caupedactylus ybaka. | May be synonymous with Tapejaridae when Caupedactylia is outside of Tapejaridae. |

| Sinopterinae | Lü et al., 2016 | The largest clade containing Sinopterus dongi, but not Tapejara wellnhoferi. | |

| Tapejaridae | Kellner, 1989 | The smallest clade containing Tapejara wellnhoferi and Sinopterus dongi. | Has had multiple interpretations of how inclusive the family is. Originally including Tapejara and relatives along with Thalassodromeus and relatives, then the last common ancestor and all descendants of Tapejara and Sinopterus, and most recently proposed as the last common ancestor Caupedactylus, Tapejara, and Sinopterus. The second interpretation is the currently most followed convention.[26] |

| Tapejariformes | Pêgas et al., 2024[26] | The clade characterized by a downturned rostrum synapomorphic with that of Tapejara | May be synonymous with Tapejaridae if Caupedactylus is a tapejarid. |

| Tapejarinae | Kellner & Campos, 2007[10] | The largest clade containing Tapejara wellnhoferi, but not Sinopterus dongi. | Has been historically treated as one of two subfamilies (the other being Thalassodrominae) in Tapejaridae. More recently, it is treated as one of the two main subfamilies along with Sinopterinae. |

| Tapejarini | Andres et al., 2014[20] | The smallest clade containing Tapejara wellnhoferi and Tupandactylus imperator |

References

[edit]- ^ Peter Wellnhofer, Eric Buffetaut (1999). "Pterosaur remains from the Cretaceous of Morocco". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 73 (1–2): 133–142. doi:10.1007/BF02987987. S2CID 129032233.

- ^ Vullo, R.; Marugán-Lobón, J. S.; Kellner, A. W. A.; Buscalioni, A. D.; Gomez, B.; De La Fuente, M.; Moratalla, J. J. (2012). Claessens, Leon (ed.). "A New Crested Pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Spain: The First European Tapejarid (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea)". PLOS ONE. 7 (7): e38900. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738900V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038900. PMC 3389002. PMID 22802931.

- ^ Mull, Olivia K.; Bennett, S. Christopher (2023-07-31). "Tapejarine pterosaur from the late Albian Paw Paw Formation of Texas, USA, with extensive feeding traces of multiple scavengers". Historical Biology. doi:10.1080/08912963.2023.2241044.

- ^ Lü, J.; Jin, X.; Unwin, D.M.; Zhao, L.; Azuma, Y.; Ji, Q. (2006). "A new species of Huaxiapterus (Pterosauria: Pterodactyloidea) from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China with comments on the systematics of tapejarid pterosaurs". Acta Geologica Sinica. 80 (3): 315–326. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2006.tb00251.x. S2CID 129851866.

- ^ a b Pinheiro, F.L.; Fortier, D.C.; Schultz, C.L.; De Andrade, J.A.F.G.; Bantim, R.A.M. (2011). "New information on Tupandactylus imperator, with comments on the relationships of Tapejaridae (Pterosauria)". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56: 567–580. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0057.

- ^ a b Eck, K.; Elgin, R.A.; Frey, E. (2011). "On the osteology of Tapejara wellnhoferi KELLNER 1989 and the first occurrence of a multiple specimen assemblage from the Santana Formation, Araripe Basin, NE-Brazil". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 130 (2): 277–296. doi:10.1007/s13358-011-0024-5. S2CID 84883165.

- ^ Wu, Wen-Hao; Zhou, Chang-Fu; Andres, Brian (2017). "The toothless pterosaur Jidapterus edentus (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea) from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota and its paleoecological implications". PLOS ONE. 12 (9): e0185486. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1285486W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185486. PMC 5614613. PMID 28950013.

- ^ Meng, X. (2008). "A New Species of Sinopterus from Jehol Biota and Reconstraction of Stratigraphic Sequence of the Jiufotang Formation". Thesis, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

- ^ Could Tapejarid Pterosaurs be the dispersers of Klitzschophyllites angiosperm? A preliminary case of study of zoocory Flaviana J. Lima 1*, Renan A. M. Bantim1,2, Antônio A. F. Saraiva1 & Juliana M. Sayão3

- ^ a b Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (2007). "Short note on the ingroup relationships of the Tapejaridae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea". Boletim do Museu Nacional. 75: 1–14.

- ^ Pêgas, R. V.; Costa, F. R.; Kellner, A. W. A. (2018). "New Information on the osteology and a taxonomic revision of the genus Thalassodromeus (Pterodactyloidea, Tapejaridae, Thalassodrominae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (2): e1443273. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1443273. S2CID 90477315.

- ^ Borja Holgado, Rodrigo V. Pêgas, José Ignacio Canudo, Josep Fortuny, Taissa Rodrigues, Julio Company & Alexander W.A. Kellner, 2019, "On a new crested pterodactyloid from the Early Cretaceous of the Iberian Peninsula and the radiation of the clade Anhangueria", Scientific Reports 9: 4940 doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41280-4

- ^ Kellner, Alexander W. A.; Caldwell, Michael W.; Holgado, Borja; Vecchia, Fabio M. Dalla; Nohra, Roy; Sayão, Juliana M.; Currie, Philip J. (2019). "First complete pterosaur from the Afro-Arabian continent: insight into pterodactyloid diversity". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 17875. Bibcode:2019NatSR...917875K. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54042-z. PMC 6884559. PMID 31784545.

- ^ Kellner, Alexander W. A.; Weinschütz, Luiz C.; Holgado, Borja; Bantim, Renan A. M.; Sayão, Juliana M. (19 August 2019). "A new toothless pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea) from Southern Brazil with insights into the paleoecology of a Cretaceous desert". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 91 (suppl 2): e20190768. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201920190768. ISSN 0001-3765. PMID 31432888.

- ^ Beccari, Victor; Pinheiro, Felipe Lima; Nunes, Ivan; Anelli, Luiz Eduardo; Mateus, Octávio; Costa, Fabiana Rodrigues (2021-08-25). "Osteology of an exceptionally well-preserved tapejarid skeleton from Brazil: Revealing the anatomy of a curious pterodactyloid clade". PLOS ONE. 16 (8): e0254789. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254789. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 8386889. PMID 34432814.

- ^ Unwin, D. M. (2003). "On the phylogeny and evolutionary history of pterosaurs". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 217 (1): 139–190. Bibcode:2003GSLSP.217..139U. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.217.01.11. S2CID 86710955.

- ^ Martill, D.M.; Naish, D. (2006). "Cranial crest development in the azhdarchoid pterosaur Tupuxuara, with a review of the genus and tapejarid monophyly". Palaeontology. 49 (4): 925–941. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00575.x.

- ^ Lü J.; D.M. Unwin; Xu L.; Zhang X. (2008). "A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China and its implications for pterosaur phylogeny and evolution". Naturwissenschaften. 95 (9): 891–7. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0397-5. PMID 18509616.

- ^ Witton, M. P. (2009). "A new species of Tupuxuara (Thalassodromidae, Azhdarchoidea) from the Lower Cretaceous Santana Formation of Brazil, with a note on the nomenclature of Thalassodromidae". Cretaceous Research. 30 (5): 1293–1300. Bibcode:2009CrRes..30.1293W. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.07.006. S2CID 140174098.

- ^ a b Andres, B.; Clark, J.; Xu, X. (2014). "The Earliest Pterodactyloid and the Origin of the Group". Current Biology. 24 (9): 1011–6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.030. PMID 24768054.

- ^ Martill, David M.; Green, Mick; Smith, Roy; Jacobs, Megan; Winch, John (April 2020). "First tapejarid pterosaur from the Wessex Formation (Wealden Group: Lower Cretaceous, Barremian) of the United Kingdom" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 113: 104487. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104487.

- ^ a b c Pêgas, R. V.; Zhoi, X.; Jin, X.; Wang, K.; Ma, W. (2023). "A taxonomic revision of the Sinopterus complex (Pterosauria, Tapejaridae) from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota, with the new genus Huaxiadraco". PeerJ. 11. e14829. doi:10.7717/peerj.14829. PMC 9922500.

- ^ a b Pêgas, Rodrigo V. (June 10, 2024). "A taxonomic note on the tapejarid pterosaurs from the Pterosaur Graveyard site (Caiuá Group, ?Early Cretaceous of Southern Brazil): evidence for the presence of two species". Historical Biology: 1–22. doi:10.1080/08912963.2024.2355664. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ Cerqueira GM, Santos MA, Marks MF, Sayão JM, Pinheiro FL (2021). "A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil and the paleobiogeography of the Tapejaridae". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 66. doi:10.4202/app.00848.2020..

- ^ Andres, Brian (December 7, 2021). "Phylogenetic systematics of Quetzalcoatlus Lawson 1975 (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (sup1): 203–217. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41S.203A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1801703. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 245078533.

- ^ a b c Pêgas, Rodrigo V. (2024). "A taxonomic note on the tapejarid pterosaurs from the Pterosaur Graveyard site (Caiuá Group, ?Early Cretaceous of Southern Brazil): Evidence for the presence of two species". Historical Biology: 1–22. doi:10.1080/08912963.2024.2355664.