Tantalus: Difference between revisions

→Sources and references: modern sources |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

The chemical element [[tantalum]] (symbol Ta, atomic number 73) is named for the mythological Tantalus. |

The chemical element [[tantalum]] (symbol Ta, atomic number 73) is named for the mythological Tantalus. |

||

See also [[pretas]], [[hungry ghosts]]. |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

Revision as of 21:13, 10 May 2008

- This article is about the mythological character. For other uses, see Tantalus (disambiguation).

In Greek mythology Tantalus (Greek Τάνταλος) was a son of Zeus [1] and the nymph Plouto [2] Thus he was a king in the primordial world, the father of a son Broteas whose very name signifies "mortals" (brotoi)[3] Other versions name his father as Tmolus "wreathed with oak,"[4] son of Sipylus, a king of Lydia. Both Tmolus and Mount Sipylus are names of mountains in ancient Lydia. Thus, like other Greek heroes such as Theseus, or the Dioskouroi, Tantalus had both a hidden, divine sire and a mortal one. Tantalus' mortal mountain-fathers placed him in Lydia; otherwise he might be located in Phrygia (Strabo, xii.8.21) or Paphlagonia, all in Asia Minor. Tantalus became one of the inhabitants of Tartarus, the deepest portion of the Underworld, reserved for the punishment of evildoers. The association of Tantalus with the underworld is underscored by the names of his mother Plouto ("riches", as in gold and other mineral wealth), and grandmother, Chthonia ("earth").

His children were Pelops—eponym of the Peloponnesus—the unfortunate Niobe, and Broteas. The identity of his wife is variously given: Dione, whose name simply means "The Goddess," perhaps the Pleiad with that name; or Eurythemista, a daughter of the river-god Xanthus; or Euryanassa, daughter of Pactolus, another river-god, both of them in Anatolia; or Clytia, the child of Amphidamantes (Graves 1960, section 108). Tantalus, through Pelops was the founder of the House of Atreus.

The geographer Strabo, quoting earlier sources, states that the wealth of Tantalus was derived from the mines of Phrygia and Mount Sipylus. Near Sipylus (modern Spil Mount), archaeological features that have been associated with Tantalus and his house since Antiquity are in fact Hittite. On Mount Yamanlar some two km east of Akpınar are two monuments mentioned by Pausanias: the tholos tomb of Tantalus (Christianized as "Saint Charalambos' tomb")[5] and the "throne of Pelops," in fact a rocky altar. A more famous rock-cut carving mentioned by Pausanias is the Great Mother of the Gods (Cybele to the Greeks), said to have been carved by Broteas, but also in fact Hittite.

Story of Tantalus

Tantalus is known for having been welcomed to Zeus' table in Olympus, like Ixion. There he too misbehaved, stole ambrosia, brought it back to his people,[6] and revealed the secrets of the gods.[7]

Tantalus offered up his son, Pelops, as a sacrifice to the gods. He cut Pelops up, boiled him, and served him up as food for the gods. The gods were said to be aware of his plan for their feast, so they didn't touch the offering; only Demeter, distraught by the loss of her daughter, Persephone, "did not realize what it was" and ate part of the boy's shoulder. Fate, ordered by Zeus, brought the boy to life again (she collected the parts of the body and boiled them in a sacred cauldron), rebuilding his shoulder with one wrought of ivory made by Hephaestus and presented by Demeter.

The revived Pelops was kidnapped by Poseidon and taken to Olympus to be the god's eromenos. Later, Zeus threw Pelops out of Olympus due to his anger at Tantalus. The Greeks of classical times claimed to be horrified by Tantalus' doings; cannibalism, human sacrifice and parricide were atrocities and taboo. Tantalus was the founder of the cursed House of Atreus in which variations on these atrocities continued. Misfortunes also occurred as a result of these acts, making the house the subject of many Greek Tragedies.

Tantalus' grave-sanctuary stood on Sipylus.[8] But hero's honours were paid him at Argos, where local tradition claimed to possess his bones.[9] On Lesbos, there was another hero-shrine in the little settlement of Polion and a mountain named for Tantalos.[10]

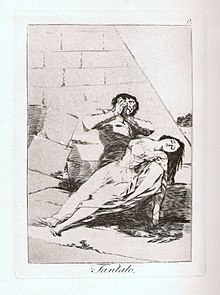

Tantalus' punishment, now proverbial for temptation without satisfaction ("tantalising"[11]), was to stand in a pool of water beneath a fruit tree with low branches. Whenever he reached for the fruit, the branches raised his intended meal from his grasp. Whenever he bent down to get a drink, the water receded before he could get any. Over his head towers a threatening stone, like that of Sisyphus.[12]

In a different story, Tantalus was blamed for indirectly having stolen the dog made of gold created by Hephaestus (god of metals and smithing) for Rhea to watch over infant Zeus. Tantalus' friend Pandareus stole the dog and gave it to Tantalus for safekeeping. When asked later by Pandareus to return the dog, Tantalus denied that he had the dog, saying he "had neither seen nor heard of a golden dog." According to Robert Graves, this incident is why an enormous stone hangs over Tantalus' head. Others state that it was Tantalus who stole the dog, and gave it to Pandareus for safekeeping.

There is a similarity between the names Tantalus and Hantili, the latter a name of two Hittite kings. Thus, there may be a loose historical connection between the mythical Tantalus and the Bronze Age Hittite kings, who likewise ruled over Asia Minor. In Robert Graves' historical novel, Hercules, My Shipmate, Graves appears to claim that Tantalus was a member of an invading Greek tribe who was condemned to his torment in Tartarus for refusing to reject his patriarchal deities in favor of a local version of Ashtoreth.

Interpretations of the Tantalus figure

The tale of Tantalus reaffirms that human sacrifice and parricide are taboo in Ancient and Classical Greek culture. Yet it seems to suggest that human sacrifice had once been offered in archaic times, especially to Demeter.

Alternatively, Tantalus can be seen as a Promethean figure who divulges divine secrets to mortals. He presides over sacred initiations consisting of mystic death and transfiguration. His dismemberment of Pelops and Pelops' resurrection can be seen as an archetypal shamanic initiation. [citation needed]

Other characters with the same name

There are two other characters named Tantalus in Greek mythology, both minor figures and both descendants of the above Tantalus. Broteas is said to have had a son named Tantalus, who ruled over the city of Pisa in the Peloponnesus. This Tantalus was the first husband of Clytemnestra. He was slain by Agamemnon, King of Mycenae, who made Clytemnestra his wife. The third Tantalus was a son of Thyestes, who was murdered by his uncle Atreus, and fed to his unsuspecting father, Thyestes.

Related terms

The name "Tantalus" is the origin of the English word "tantalise". The idea being that when a person tantalises someone else, that person is making them like Tantalus: there is something desirable that is always just out of that person's reach.

A Tantalus, by an obvious analogy, is also the term for a type of drinks decanter stand in which the bottle stoppers are firmly clamped down by a locked metal bar, as a means of preventing servants from stealing the master's liquor. The decanters themselves, however, remain clearly visible.

The chemical element tantalum (symbol Ta, atomic number 73) is named for the mythological Tantalus.

See also pretas, hungry ghosts.

Notes

- ^ Euripides, Orestes.

- ^ Plouto is not to be confused with the god of the underworld. Lydia was rich in gold.

- ^ Noted by Kerenyi 1959:57.

- ^ A scholium on Euripides.

- ^ Various sites called the "tomb of Tantalus" have been shown to travellers since the time of Pausanias; the most accessible today is in İzmir (ancient Smyrna), a monumental work that is actually the tomb of a sixth-century ruler.

- ^ Pindar, TFirst Olympian Ode.

- ^ Euripides, Orestes, 10.

- ^ Pausanias, 2.22.3.

- ^ Pausanias, 2.22.2.

- ^ Stephen of Byzantium, noted by Kerenyi 1959:57, note 218.

- ^ Dictionary.com - tantalize

- ^ This detail was added to the myth by the painter Polygnotus, according to Pausanias (10.31.12), noted in Kerenyi 1959:61.

Ancient sources

- Homer, Odyssey XI, 582-92

- Apollodorus, Bibliotheke III, v, 6

- Apollodorus, Epitome II,1-3

- Ovid, Metamorphoses IV, 458-9; VI, 172- 76 & 403-11.

Modern sources

- Calimach, Andrew (2002). Lovers' Legends: The Gay Greek Myths. New Rochelle: Haiduk Press.

- Gantz, Timothy (1993). Early Greek Myth. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Graves, Robert (1960, 1962). The Greek Myths.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Kerenyi, Karl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. New York/London: Thames and Hudson.pp 57-61 et passim

- Sergent, Bernard (1986). Homosexuality in Greek Myth. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911: "Tantalus"

External links

- The story of Tantalus, fully developed compiled from selected primary sources to highlight the shamanic and promethean aspects of the story. By Pindar's time this view would have been rejected.

Spoken-word myths - audio files

| The Tantalus myth as told by story tellers |

|---|

| 1. Zeus and Tantalus, (including Pelops and Poseidon), read by Timothy Carter |

| Bibliography of reconstruction: Homer, Odyssey, 11.567 (7th c. BCE); Pindar, Olympian Odes, 1 (476 BCE); Euripides, Orestes, 12-16 (408 BCE); Apollodorus, Epitomes 2: 1-9 (140 BCE); Ovid, Metamorphoses, VI: 213, 458 (8 CE); Hyginus, Fables, 82: Tantalus; 83: Pelops (1st c. CE); Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.22.3 (160 - 176 CE) |