Tanganyika Territory

Tanganyika Territory | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1916–1961 | |||||||||

| Anthem: God Save the King (1916–1952) God Save the Queen (1952–1961) | |||||||||

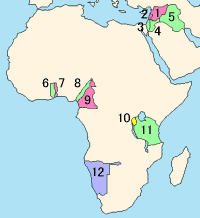

League of Nations mandates in the Middle East and Africa, with no. 11 representing Tanganyika | |||||||||

| Status | Mandate of the United Kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital | Dar es Salaam | ||||||||

| Common languages | English (official) | ||||||||

| Religion | Protestantism, Catholicism, Islam and others. | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

• 1916–1936 | George V | ||||||||

• 1952–1961 | Elizabeth II | ||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

• 1916–1925 | Horace Archer Byatt | ||||||||

• 1958–1961 | Richard Turnbull | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 1916 | |||||||||

• Mandate created | 20 July 1922 | ||||||||

• Independence | 9 December 1961 | ||||||||

| Currency | East African shilling | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Tanzania | ||||||||

Tanganyika was a colonial territory in East Africa which was administered by the United Kingdom in various guises from 1916 until 1961. It was initially administered under a military occupation regime. From 20 July 1922, it was formalised into a League of Nations mandate under British rule. From 1946, it was administered by the UK as a United Nations trust territory. It bordered British East Africa to the North East

Before World War I, Tanganyika formed part of the German colony of German East Africa. It was gradually occupied by forces from the British Empire and Belgian Congo during the East Africa Campaign, although German resistance continued until 1918. After this, the League of Nations formalised control of the area by the UK, who renamed it "Tanganyika". The UK held Tanganyika as a League of Nations mandate until the end of World War II after which it was held as a United Nations trust territory. In 1961, Tanganyika gained its independence from the UK as Tanganyika, joining the Commonwealth. It became a republic a year later. Tanganyika now forms part of the modern-day sovereign state of Tanzania.[1]

Etymology

[edit]The name of the territory was taken from the large lake in its west. Henry Morton Stanley had found the name of "Tanganika", when he travelled to Ujiji in 1876. He wrote that the locals were not sure about its meaning and conjectured that it meant something like "the great lake spreading out like a plain", or "plain-like lake".[2]

The name was chosen by the British with the Treaty of Versailles, and as such the name took effect when Britain was given control of Tanganyika in 1920. Britain needed a new name to replace "Deutsch Ostafrika" or "German East Africa". Various names were considered, including "Smutsland" in honour of General Jan Smuts (denied for being "inelegant"), "Eburnea", "New Maryland", "Windsorland" after the British Royal Family's new family name, and "Victoria" after both the Lake and the Queen. The Colonial Secretary insisted that "a native name prominently associated with the territory" be selected. "Kilimanjaro", analogous to "Kenya", named after the country's highest mountain, and "Tabora", after the town and trading centre near the geographical centre of the country, were proposed and rejected. Then, the deputy undersecretary to the Colonial Secretary proposed "Tanganyika Protectorate" after Lake Tanganyika; the name was modified after a "junior official suggested that 'Territory' was more in accordance with the [League of Nations mandate]" and that was adopted.[3]

History

[edit]

The area that made up Tanganyika was commonly visited by Arabic traders who would come to the area to buy enslaved people and smuggle ivory. The island of Zanzibar was even taken as a part of the Sultanate of Oman; when Seyyid Said came to power in 1806, Omani interests in Tanzania began to increase. During the early 19th century, with British support, Oman began developing in the region more closely to prevent French growth in the Indian Ocean and grow Oman's wealth and influence.[4] Trade caravans began venturing further into the continent, connecting the coast and the interior together. In some areas, Islam became adopted by the native peoples, such as the Yao in the south of the country. Islam has continued to be a major religion within the area, with 36% of the Tanzanian population adhering to Islam.[5]

In the second half of the 19th century, European explorers and colonialists travelled through the African interior from Zanzibar. In 1885, the German Empire declared its intent to establish a protectorate in the area, named German East Africa (GEA), under the leadership of Carl Peters. When the Sultan of Zanzibar objected, German warships threatened to bombard his palace. Britain and Germany then agreed to divide the mainland into various spheres of influence, and the Sultan was forced to acquiesce. The Germans brutally repressed the Maji Maji Rebellion of 1905. The German colonial administration instituted an educational program for native Africans, including elementary, secondary, and vocational schools.[6][7][page needed]

The German colonial administrations developed the colony through several means. Cultivation of several profitable cash crops such as cotton, sisal, cocoa and coffee was important to developing the colony as these resources were used for German consumers and industry. Sisal was especially valuable to rope production, and was one of German East Africa's largest exports. In 1893 there was only one sisal plantation in the country; by 1913 there were 54. In 1913, the country exported over 20,000 tons of sisal, 30% of total exports.[8] To ensure that these resources could be moved easily, several railways were built. The most important of these was the Mittellandbahn (Central Line, which connected much of the country with the port city of Dar es Salaam. This railroad is still in use today and has since been connected to other railways across the country.

After Germany's defeat during World War I, GEA was divided among the victorious powers under the Treaty of Versailles. Apart from Ruanda-Urundi (assigned to Belgium) and the small Kionga Triangle (assigned to Portuguese Mozambique), the territory was transferred to British control. "Tanganyika" was adopted by the British as the name for its part of the former German East Africa. On 22 March, 1921 Belgium ceded the Kigoma District to Tanganyika.[9]

In 1927, Tanganyika entered the Customs Union of the East Africa Protectorate and the Uganda Protectorate, which eventually became the independent countries of Kenya and Uganda, and the East African Postal Union, later the East African Posts and Telecommunications Administration. Cooperation expanded with those protectorates and, later, countries in a number of ways, leading to the establishment of the East African High Commission (1948–1961) and the East African Common Services Organisation (1961–1967), forerunners of the East African Community. The country held its first elections in 1958 and 1959. The following year it was granted internal self-government and fresh elections were held. Both elections were won by the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), which led the country to independence in December 1961. The following year a presidential election was held, with TANU leader Julius Nyerere emerging victorious. In the mid-20th century, Tanganyika was the largest producer of beeswax in the world.[10]

The British state took control of the colony of Tanganyika as a result of the Treaty of Versailles. Once Britain took control of the colony, they wished it to be a "Black man's country", similar to Nigeria in terms of its state structure. And as the policy of colonial rule in Nigeria changed to indirect rule so too did the governance of Tanganyika. The British also pursued an anti-German policy which was led by the head official in Tanganyika, Sir Horace Bryatt. Bryatt was an unpopular politician, and his policies of expelling Germans halved Tanganyika's European population. Many of the ex-German plantations were sold to European companies and mixed farms were given to new British owners. Much of Tanganyika's economy was based around cash crops, in particular coffee.[11]

British rule did have positives for the Asian community living in Tanganyika. Under Britain's protection, they were no longer attacked as they were during the war. Many of them were employed from the Indian administration to work for the Tanganyikan administration. This led to the Asian population in Tanganyika increasing from 8,698 in 1912 to 25,144 in 1931.[11]

One of the major drivers for decolonisation in Tanganyika was TANU which was founded in 1954, led by Julius Nyerere.[12] In 1963, TANU opened its doors to all members of society within Tanganyika, whereas it had previously only been open to Africans.[13]

The success of TANU can be seen in the 1958 election under colonial rule where TANU candidates or TANU-supported candidates won every seat. The majority of the voters in Tanganyika were African, approximately two-thirds of the 28,500 registered voters,[13] with them coming from across the country.

There was some resistance, though, from the British settlers who established the United Tanganyikan Party (UTP) by Brian Willis in 1956. However, the party became redundant as it was clear that Nyerere and TANU were going to win the battle over Tanganyikan independence. UTP was less effective due to the £4,000 annual salary for Willis which limited the party's effectiveness, as they lacked funds to campaign effectively.[14]

Tanganyika eventually gained its independence on 9 December 1961,[15] after Nyerere had met a British government representative to arrange the steps to be taken on the road to independence.[11]

Notable people

[edit]- David Gordon Hines (1915-2000), an accountant, military officer and civil servant

- Julius Nyerere (1922–1999), an anti-colonial activist, politician and political theorist

- Vasant Tapu (1936–1988), a cricketer

- Ebrahim Hussein (born 1943), a playwright and poet

- Clive Elliott (1945–2018), a British ornithologist and international civil servant

- Dudley Seaton (1953–1978), son of Alberta Jones Seaton, a zoologist involved in African independence movements

- Juma Mkambi (1955–2010), a footballer

- Tim Macartney-Snape (born 1956), a mountaineer and author

- Kipruto Rono Arap Kirwa (born 1957), a Kenyan politician

Tanganyikan independence

[edit]The British colony of Tanganyika gained independence on 9 December 1961, with Julius Nyerere becoming its first prime minister in 1960 under British rule, and then president when Tanganyika was declared a republic in 1962. The main leader of the independence movement was undoubtedly Nyerere, who led the party TANU, which was a socially diverse group which had shared demands for independence from Britain.[16] TANU gained most of its political support through national issues. For example, TANU, discussed and promoted fears that the colonial state had attempted to give a disproportionate amount of power to the European and Asian minority groups living within Tanganyika. This would have undermined the entire basis of Tanganyika independence. TANU installed a deep-rooted fear within the African population that the colonialists might still rule or have influence, even after independence.[17]

Challenges after independence

[edit]Although independence came peacefully for Tanganyika, the country suffered from similar problems with many other post-colonial African countries such as poor financial resources and inadequate levels of infrastructure. However, two of the main factors that burdened Tanganyika's independence were its geography and its surrounding neighbours. The destabilising conflicts that bordered Tanganyika meant that refugees from the Congo, Burundi, and Rwanda often flooded into Tanganyika.[18] The influx of refugees was a huge issue for Tanganyika so soon after independence. These challenges only emphasised the insecurities of Tanganyika and its people. In addition, Nyerere's growing emphasis on modernisation and his African socialist ideology known as Ujamaa saw many rural farmers' livelihoods destroyed by encroaching agriculturalists.

In 1964, after the Zanzibar Revolution which saw the Arab rule of Zanzibar overthrown, Tanganyika merged with Zanzibar to become the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar, which later became known as the United Republic of Tanzania on 26 April 1964.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Awesome List of Countries Starting with Each Alphabet Letter (From A To Z) - Tymoff Today". 16 July 2024. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Stanley, Henry M. (1878). Through the Dark continent, or, The sources of the Nile : around the great lakes of equatorial Africa and down the Livingstone River to the Atlantic Ocean, Volume II. Harold B. Lee Library. London : Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, Rivington. p. 16.

- ^ Iliffe, John (1979). A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780521296113.

- ^ Kimambo, N. and Maddox, H. (2017) A New History of Tanzania. Oxford: Mkuki Na Nyota Publishers

- ^ "Faith and Development in Focus, Tanzania" (PDF). World Faiths Development Dialogue. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ East, John William. "The German Administration in East Africa: A Select Annotated Bibliography of the German Colonial Administration in Tanganyika, Rwanda and Burundi from 1884 to 1918." [London? 1989] 294 leaves. 1 reel of microfilm (negative.) Thesis submitted for the fellowship of the Library Association, London, November 1987.

- ^ Farwell, Byron. The Great War in Africa, 1914–1918. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. 1989. ISBN 0-393-30564-3

- ^ Nganang, Alain Patrice; Mühlhahn, Klaus; and Berman Nina. German Colonialism Revisited: African, Asian, and Oceanic Experiences. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2014. page 114

- ^ Ofcansky, Thomas P.; Yeager, Rodger (1997). Historical dictionary of Tanzania. African historical dictionaries (2nd ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8108-3244-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Gunther, J. (1955). Inside Africa. Harper. p. 409. ISBN 0836981979. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Iliffe, John (1979). A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 262–566. ISBN 9780521296113.[page range too broad]

- ^ Shivji, Issa (2015). Pan-Africanism or Pragmatism?: lessons of the Tanganyika-Zanzibar Union. Addis Ababa: Dar es Salaam. pp. 70–71. ISBN 9789987449996.

- ^ a b Bienen, Henry (2015). Tanzania: Party Transformation and Economic Development. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780691000121.

- ^ Murphy, Phillip (1995). Party Politics ad Decolonization: The Conservative Party and British Colonial Policy in Tropical Africa 1951–1964. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 9780198205050.

- ^ Institut Francais de recherche en Afrique (2015). Remembering Julius Nyerere in Tanzania: history, memory, legacy. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki Na Nyota. p. 35. ISBN 978-9987-753-47-5.

- ^ Leys, Colin (1962). "Tanganyika: The Realities of Independence". International Journal. 17 (3): 251–68. doi:10.2307/40198635. JSTOR 40198635. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Bjerk, Paul (2015). Building a Peaceful Nation (1st ed.). Boydell & Brewer. p. Chapter 3, Paragraph 1.

- ^ Bjerk, Paul (2015). Building a Peaceful Nation. Boydell & Brewer. p. Chapter 3, Paragraph 6.

- ^ Ewald, Jonas (2013). Challenges for the Democratisation Process in Tanzania (1st ed.). Mkuki na Nyota Publishers. p. Chapter 4.3, Paragraph 15.

Further reading

[edit]- Cana, Frank Richardson (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 32 (12th ed.). pp. 676–677.

- Gordon-Brown, A., ed. (1954). The East Africa Year Book and Guide. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hill, J. F. R.; Moffett, J. P. (1955). Tanganyika – a Review of its Resources and their Development. Government of Tanganyika. — 924pps, with many maps

- Iliffe, John (10 May 1979). A modern history of Tanganyika. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29611-3.

- Moffett, J. P. (1958). Handbook of Tanganyika. Government of Tanganyika. — 703pps, with maps

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2008). Life in Tanganyika in The Fifties. New Africa Press. — 428pps, with maps and photos