Table Mountain

| Table Mountain | |

|---|---|

| Huriǂoaxa Tafelberg | |

View of Table Mountain and Cape Town seen from Bloubergstrand. Table Mountain is flanked by Devil's Peak on the left and Lion's Head on the right, with about 5,2 km distance between them.[1] | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,084.6 m (3,558 ft)[2] |

| Prominence | 1,068 m (3,504 ft)[3] |

| Listing | List of mountains in South Africa |

| Coordinates | 33°57′26.33″S 18°24′11.19″E / 33.9573139°S 18.4031083°E |

| Geography | |

Cape Town, South Africa | |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | Silurian/Ordovician |

| Mountain type | Sandstone |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | António de Saldanha, 1503 |

| Easiest route | Platteklip Gorge |

Table Mountain (Khoekhoe: Huriǂoaxa, lit. 'sea-emerging'; Afrikaans: Tafelberg) is a flat-topped mountain forming a prominent landmark overlooking the city of Cape Town in South Africa. It is a significant tourist attraction, with many visitors using the cableway or hiking to the top.[4] Table Mountain National Park is the most visited national park in South Africa, attracting 4.2 million people every year for various activities. The mountain has 8,200 plant species, of which around 80% are fynbos, meaning fine bush.[5] It forms part of the Table Mountain National Park, and part of the lands formerly ranged by Khoe-speaking clans, such as the !Uriǁʼaes (the "High Clan"). It is home to a large array of mostly endemic fauna and flora.[6] Its top elevates about 1,000 m above the surrounding city, making the popular hike upwards on a large variety of different, often steep and rocky pathways a serious mountain tour which requires fitness, preparation and hiking equipment.

Features

[edit]

The main feature of Table Mountain is the level plateau approximately three kilometres (2 mi) from side to side, edged by steep cliffs. The plateau, flanked by Devil's Peak to the east and by Lion's Head to the west, forms a dramatic backdrop to Cape Town. This broad sweep of mountainous heights, together with Signal Hill, forms the natural amphitheatre of the City Bowl and Table Bay harbour. The highest point on Table Mountain is towards the eastern end of the plateau and is marked by Maclear's Beacon, a stone cairn built in 1865 by Sir Thomas Maclear for trigonometrical survey. It is 1,086 metres (3,563 ft) above sea level, and about 19 metres (62 ft) higher than the cable station at the western end of the plateau.

The cliffs of the main plateau are split by Platteklip Gorge ("Flat Stone Gorge"), which provides an easy and direct ascent to the summit and was the route taken by António de Saldanha on the first recorded ascent of the mountain in 1503.[7]

The flat top of the mountain is often covered by orographic clouds, formed when a southeasterly wind is directed up the mountain's slopes into colder air, where the moisture condenses to form the so-called "table cloth" of cloud. Legend attributes this phenomenon to a smoking contest between the Devil and a local pirate called Van Hunks.[8] When the table cloth is seen, it symbolizes the contest.

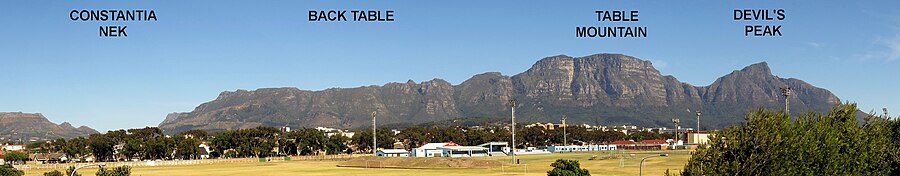

Table Mountain is at the northern end of a sandstone mountain range that forms the spine of the Cape Peninsula that terminates approximately 50 kilometres (30 mi) to the south at the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Point. Immediately to the south of Table Mountain is a rugged "plateau" at a somewhat lower elevation than the Table Mountain Plateau (at about 1,000 m or 3,300 ft), called the "Back Table". The "Back Table" extends southwards for approximately 6 km to the Constantia Nek-Hout Bay valley. The Atlantic side of the Back Table is known as the Twelve Apostles, which extends from Kloof Nek (the saddle between Table Mountain and Lion's Head) to Hout Bay. The eastern side of this portion of the Peninsula's mountain chain, extending from Devil's Peak, the eastern side of Table Mountain (Erica and Fernwood Buttresses), and the Back Table to Constantia Nek, does not have a single name, as on the western side. It is better known by the names of the conservation areas on its lower slopes: Groote Schuur Estate, Newlands Forest, Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens, Cecilia Park, and Constantia Nek.

Geology

[edit]

The upper approximately 600-metre (2,000 ft) portion of the one-kilometre-high (0.62 mi) table-topped mountain, or mesa, consists of 450- to 510-million-year-old (Ordovician) rocks belonging to the two lowermost layers of the Cape Fold Mountains.[9][10] The uppermost, and younger of the two layers, consists of extremely hard quartzitic sandstone, commonly referred to as "Table Mountain Sandstone" (TMS), or "Peninsula Formation Sandstone" (as it is known as at present), which is highly resistant to erosion and forms characteristic steep grey crags. The 70-metre-thick (230 ft) lower layer, known as the "Graafwater Formation", consists of distinctively maroon-colored mudstones, which were laid down in much thinner horizontal strata than the Table Mountain Sandstone strata above it.[9] The Graafwater rocks can best be seen just above the contour path on the front of Table Mountain, and around Devils Peak. They can also been seen in the cutting along Chapman's Peak Drive. These rocks are believed to have originated in shallow tidal flats, in which a few Ordovician fossils, and fossil tracks have been preserved.[9][11] The overlying TMS probably arose in deeper water, either as a result of subsidence, or a rise in the sea level.[9][11] The Graafwater rocks rest on the basement consisting of Cape Granite. Devil's Peak, Signal Hill, the City Bowl and much of the "Cape Flats", however, rest on heavily folded and altered phyllites and hornfelses known informally as the Malmesbury shales. The Cape Granite and Malmesbury shales form the lower, gentler slopes of the Table Mountain range on the Cape Peninsula. They are of late Precambrian age, pre-dating the "Graafwater rocks" by at least 40 million years.[9]

The basement rocks are not nearly as resistant to weathering as the TMS, but significant outcrops of the Cape Granite are visible on the western side of Lion's Head, and elsewhere on the Peninsula (especially below Chapman's Peak Drive, and The Boulders near Simon's Town).[9][12][13] The weathered granite soil of the lower slopes of the Peninsula Mountain range are more fertile than the nutrient-poor soils derived from TMS. Most of the vineyards found on the Cape Peninsula are therefore found on these granitic slopes of the Table Mountain range.

The mountain owes its table-top flatness to the fact that it is a syncline mountain, meaning that it was once the floor of a valley (see diagram on the right). The anticline, or highest point of the series of folds that Table Mountain was once part of, lay to the east, but that has been weathered away, together with the underlying softer Malmesbury shale and granite basement, to form the "Cape Flats", the isthmus that connects the Cape Peninsula to the mainland. The fold mountains reappear as the Hottentots-Holland Mountain range on the mainland side of the Cape Flats.[9] What has added to the mountain's table-top flatness is that it consists entirely of the very hard, lower layer of the TMS Formation. Originally this was topped by a thin glacial tillite layer, known as the Pakhuis Formation (see the diagram above, left), above which was the upper layer of TMS. Both these layers, but especially the tillite layer, are softer than the lower layer of Table Mountain Sandstone. When these softer layers eroded away, they left a very hard, flat erosion-resistant quartzitic sandstone platform behind which today forms Table Mountain's top.

Table Mountain is the northernmost end of a 50-kilometre-long (30 mi) and roughly six-to-ten-kilometre-wide (4 to 6 mi) Cape Fold Mountain range that forms the backbone of the Cape Peninsula, stretching from the Cape of Good Hope in the south to Table Mountain and its flanking Devil's Peak (to the east) and Lion's Head and Signal Hill (to the west) in the north. Table Mountain forms the highest point of this range. The range runs parallel to the other Cape Fold Mountain ranges on the mainland to the east.

Flora

[edit]

Table Mountain and the Back Table have an unusually rich biodiversity. Its vegetation consists predominantly of several different types of the unique and rich Cape fynbos. The main vegetation type is endangered Peninsula Sandstone Fynbos, but critically endangered Peninsula Granite Fynbos, Peninsula Shale Renosterveld and Afromontane forest occur in smaller portions on the mountain.

Table Mountain's vegetation types form part of the Cape Floral Region protected areas. These protected areas are a World Heritage Site, and an estimated 2,285 species of plants are confined to Table Mountain and the Cape Peninsula range, of which a great proportion, including many species of proteas, are endemic to these mountains and valleys and can be found nowhere else.[17][18] Of the 2,285 species on the Peninsula 1,500 occur in the 57 km2 area comprising Table Mountain and the Back Table, a number at least a large as all the plant species in the whole of the United Kingdom.[17] The Disa uniflora, despite its restricted range within the Western Cape, is relatively common in the perennially wet areas (waterfalls, streamlets and seeps) on Table Mountain and the Back Table, but hardly anywhere else on the Cape Peninsula.[16][19] It is a very showy orchid that blooms from January to March on the Table Mountain Sandstone regions of the mountain. Although they are quite widespread on the Back Table, the best (most certain, and close-up) place to view these beautiful blooms is in the "Aqueduct" off the Smuts Track, halfway between Skeleton Gorge and Maclear's Beacon.

Remnant patches of indigenous forest persist in the wetter ravines. However, much of the indigenous forest was felled by the early European settlers for fuel for the lime kilns needed during the construction of the Castle.[20] The exact extent of the original forests is unknown, though most of it was probably along the eastern slopes of Devil's Peak, Table Mountain and the Back Table where names such as Rondebosch, Kirstenbosch, Klassenbosch and Witteboomen survive (in Dutch "bosch" means forest; and "boomen" means trees). Hout Bay (in Dutch "hout" means wood) was another source of timber and fuel as the name suggests.[20] In the early 1900s commercial pine plantations were planted on these slopes all the way from the Constantiaberg to the front of Devil's Peak, and even on top of the mountains, but these have now been largely cleared allowing fynbos to flourish in the regions where the indigenous Afromontane forests have not survived, or never existed.

Fynbos is a fire adapted vegetation, and providing fires are not too frequent, regular or intense, they are important drivers of fynbos diversity.[21] Regular fires have dominated fynbos for at least the past 12 000 years largely as a result of human activity.[18][22] In 1495 Vasco da Gama named the South African coastline Terra de Fume because of the smoke he saw from numerous fires.[23] This was originally probably to maintain a productive stock of edible bulbs (especially watsonians)[23] and to facilitate hunting, and later, after the arrival of pastoralists,[24] to provide fresh grazing after the rains.[23][22] Thus the plants that make up fynbos today are those that have been subjected to a variety of fire regimes over a very long period time, and their preservation now requires regular burning. The frequency of the fires obviously determines precisely which mix of plants will dominate any particular region,[25] but intervals of 10–15 years between fires[17] are considered to promote the proliferation of the larger Protea species, a rare local colony of which, the Aulax umbellata (Family: Proteaceae), was wiped out on the Peninsula by more frequent fires,[25] as have been the silky-haired pincushion, Leucospermum vestitum, the red sugarbush, Protea grandiceps and Burchell's sugarbush, Protea burchellii, although a stand of a dozen or so plants has recently been "rediscovered" in the saddle between Table Mountain and Devil's Peak.[23] Some bulbs may similarly have become extinct as a result a too rapid sequence of fires.[25] The fires that occur on the mountains today are still largely due to unregulated human activity. Fire frequency is therefore a matter of chance rather than conservation.

Despite intensive conservation efforts the Table Mountain range has the highest concentration of threatened species of any continental area of equivalent size in the world.[17][26] The non-urban areas of the Cape Peninsula (mainly on the mountains and mountain slopes) have suffered particularly under a massive onslaught of invasive alien plants for well over a century, with perhaps the worst invader being the cluster pine, partly because it was planted in extensive commercial plantations along the eastern slopes of the mountains, north of Muizenberg. Considerable efforts have been made to control the rapid spread of these invasive alien trees. Other invasive plants include black wattle, blackwood, Port Jackson and rooikrans (All Australian members of the acacia family), as well as several Hakea species and bramble.[17][25][27][28]

Fauna

[edit]The most common mammal on the mountain was the dassie (the South African name, from Afrikaans, pronounced "dussy"), or rock hyrax. Between about 2000 and 2004 (no one is certain about the exact year or years) their numbers suddenly plummeted for unknown reasons. They used to cluster around the restaurant at the upper cable station, near areas where tourists discarded or (inadvisably) supplied food. The population crash of the dassies may have been responsible for the decline in the Verreaux's eagle population on the Peninsula, which is believed to have consisted of three breeding pairs during the period 1950-1990, with only two pairs, maximally, ever having been reported to fledge a chick each in any given year.[29] With the commencement of formal monitoring in 1993, two breeding pairs were recorded on the Cape Peninsula Mountain Chain in 2004: one below the upper cable station at the western end of Table Mountain, in Blinkwater Ravine, the other on the cliffs below Noordhoek Peak.[30] The nest near the cable station was abandoned in 2006, leaving only the Noordhoek pair, which continued to fledge chicks reasonably regularly until 2013, at which point one member of the pair disappeared. From 2013 until January 2017 only a single Verreaux's Eagle, presumed to be a female, remained on the Peninsula. She continued to maintain the nest under Noordhoek Peak, but seemed unable to attract a mate. But in early 2017 a pair of eagles was seen by at least 7 independent observers during the course of 10 days (27 January – 5 February). Dassies are an important part the Verreaux's eagle's prey on the Peninsula.[31] (See Foot note[nb 1])

Table Mountain is also home to porcupines, mongooses, snakes, lizards, tortoises, and a rare endemic species of amphibian that is only found on Table Mountain, the Table Mountain ghost frog. The last lion in the area was shot circa 1802. Leopards persisted on the mountains until perhaps the 1920s but are now extinct locally. Two smaller, secretive, nocturnal carnivores, the rooikat (caracal) and the vaalboskat (also called the vaalkat or Southern African wildcat) were once common in the mountains and the mountain slopes. The rooikat continues to be seen on rare occasions by mountaineers but the status of the vaalboskat is uncertain. The mountain cliffs are home to several raptors species, apart from the Verreaux's eagle. They include the jackal buzzard, booted eagle (in summer), African harrier-hawk, peregrine falcon and the rock kestrel.[31][32] In 2014 there were four pairs of African fish eagles on the Peninsula, but they nest in trees generally as far away from human habitation and activity as is possible on the Peninsula.

Up until the late 1990s baboons lived on all the mountains of the Peninsula, including the Back Table immediately behind Table Mountain. Since then they have abandoned Table Mountain and the Back Table, and only occur south of Constantia Nek. They have also abandoned the tops of many of the mountains, in favor of the lower slopes, particularly when these were covered in pine plantations which seemed to provide them with more, or higher quality food than the fynbos on the mountain tops. However these new haunts are also within easy reach of Cape Town's suburbs, which brings them into conflict with humans and dogs, and the risk of traffic accidents. There are now (2014) a dozen troops on the Peninsula, varying in size from 7 to over 100 individuals, scattered on the mountains from the Constantiaberg to Cape Point.[33][34] The baboon troops are the subject of intense research into their physiology, genetics social interactions and habits. In addition, their sleeping sites are noted each evening, so that monitors armed with paint ball guns can stay with the troop all day, to ward them off from wandering into the suburbs. From when this initiative was started in 2009 the number of baboons on the Peninsula has increased from 350 to 450, and the number of baboons killed or injured by residents has decreased.[34]

Himalayan tahrs, fugitive descendants of tahrs that escaped from Groote Schuur Zoo in 1936, used to be common on the less accessible upper parts of the mountain. As an exotic species, they were almost eradicated through a culling programme initiated by the South African National Parks to make way for the reintroduction of indigenous klipspringers. Until recently there were also small numbers of fallow deer of European origin and sambar deer from southeast Asia. These were mainly in the Rhodes Memorial area but during the 1960s they could be found as far afield as Signal Hill. These animals may still be seen occasionally despite efforts to eliminate or relocate them.

On the lower slopes of Devil's Peak, above Groote Schuur Hospital an animal camp bequeathed to the City of Cape Town by Cecil John Rhodes has been used in recent years as part of the Quagga Project.[35] The quagga used to roam the Cape Peninsula, the Karoo and the Free State in large numbers, but were hunted to extinction during the early 1800s. The last quagga died in an Amsterdam zoo in 1883. In 1987 a project was launched by Reinhold Rau to back-breed the quagga, after it had been established, using mitochondrial DNA obtained from museum specimens, that the quagga was closely related to the plains zebra, and on 20 January 2005 a foal considered to be the first quagga-like individual because of a visible reduced striping, was born. These quagga-like zebras are officially known as Rau quaggas, as no one can be certain that they are anything more than quagga look-alikes. The animal camp above Groote Schuur Hospital has several good looking Rau quaggas, but they are unfortunately not easily seen except from within the game camp, which is quite large and undulating, and the animals are few. The animal camp is not open to the public.

History

[edit]

Prehistoric inhabitation of the district is well attested (see for example the article on Fish Hoek). About 2000 years ago the Khoe-speaking peoples migrated towards the Cape Peninsula from the north. This countryside was before that occupied by nomadic !Ui speakers (who were foragers). The pastoralist influx brought herds of cattle and sheep into the region, which then formed part of a larger grazing land that was seasonally rotated. It was the !Uriǁʼaekua ("Highclansmen", often written in Dutch as Goringhaiqua) who were the dominant local people when the Europeans first sailed into Table Bay. This clan is said to be the ancestral population of the !Ora nations of today (so-called "Korana" people).

These original inhabitants of the area so-called "Khoekhoen", called Table Mountain Huriǂ'oaxa – "ocean-emerging (mountain)".[36][37]

António de Saldanha was the first European to land in Table Bay. He climbed the mighty mountain in 1503 and named it Taboa do Cabo (Table of the Cape, in his native Portuguese). The great cross that the Portuguese navigator carved into the rock of Lion's Head is still traceable.

In 1796, during the British occupation of the Cape, Major-General Sir James Craig ordered three blockhouses to be built on Table Mountain: the King's blockhouse, Duke of York blockhouse (later renamed Queen's blockhouse) and the Prince of Wales blockhouse. Two of these are in ruins today, but the King's blockhouse is still in good condition.[38][39][40] and easily accessible from the Rhodes Memorial.

Between 1896 and 1907, five dams, the Woodhead, Hely-Hutchinson, De Villiers, Alexandria and Victoria reservoirs, were opened on the Back Table to supply Cape Town's water needs. A ropeway ascending from Camps Bay via Kasteelspoort ravine was used to ferry materials and manpower (the anchor points at the old top station can still be seen). There is a well-preserved steam locomotive from this period housed in the Waterworks Museum at the top of the mountain near the Hely-Hutchinson dam. It had been used to haul materials for the dam across the flat top of the mountain. Cape Town's water requirements have since far outpaced the capacity of the dams and they are no longer an important part of the water supply.

Arguments for a national park on the Cape Peninsula, centred on Table Mountain, began in earnest in the mid-1930s. Following a big fire in 1986, the Cape Times started a 'save the mountain' campaign, and in 1989 the Cape Peninsula Protected Natural Environment (CPPNE) area was established. However, environmental management was still bedeviled by the fragmented nature of land ownership on the Peninsula. Following another big fire in 1991, Attorney General Frank Kahn was appointed to reach consensus on a plan for rationalizing management of the CPPNE. In 1995, Prof. Brian Huntley recommended that SANParks be appointed to manage the CPPNE, with an agreement signed in April 1998 to transfer around 39,500 acres to SANParks. On 29 May 1998, then-president Nelson Mandela proclaimed the Cape Peninsula National Park. The park was later renamed to the Table Mountain National Park.[41]

Fires are common on the mountain. The most recent major fires include those of January 2006, which burned large amounts of vegetation and resulted in the death of a tourist (a charge of arson and culpable homicide was laid against a British man who was suspected of starting the blaze), and March 2015.[42] There was a major fire in April 2021 that affected the Rhodes Memorial and the University of Cape Town.[43]

In November 2011, Table Mountain was named one of the New7Wonders of Nature.[44]

Cableway

[edit]

The Table Mountain Aerial Cableway[45] takes passengers from the lower cable station on Tafelberg Road, about 302 metres (991 ft) above sea level, to the plateau at the top of the mountain, at 1,067 metres (3,501 ft). The upper cable station offers views overlooking Cape Town, Table Bay, Lion's Head and Robben Island to the north, and the Atlantic seaboard to the west and south. The top cable station includes curio shops, a restaurant and walking trails of various lengths.

The original cableway construction was awarded to Adolf Bleichert & Co. of Leipzig, Germany,[46] in 1926 and the cableway opened on 4 October 1929.

The cableway has been refurbished three times since its inauguration in 1929, with upgrades to the upper and lower cable stations and enlarged gondolas. The first refurbishment occurred in 1958, the second in 1974, and the third and most significant reconstruction from 1996 to 1997, introducing a "Rotair" gondola manufactured by the Swiss company Garaventa AG – CWA (Doppelmayr Garaventa Group) which increased the capacity from 20 to 65 passengers per trip and provided a faster journey to the summit. The gondolas rotate through 360 degrees during the ascent or descent, giving a panoramic view over the city.

Activities

[edit]Hiking on Table Mountain

[edit]Hiking on Table Mountain is popular amongst locals and tourists, and a number of trails of varying difficulty are available. Because of the steep cliffs around the summit, direct ascents from the city side are limited. Platteklip Gorge, a prominent gorge up the centre of the main table, is a popular and straightforward direct ascent to the summit. Par for the course is about 2.5 hours depending on fitness. This route is very hot in summer, as it is located on the north facing slope of the mountain, with almost no shade along the 600 m climb from Tafelberg Road to the Table Mountain plateau.

Longer routes to the summit go via the Back Table, a lower area of Table Mountain south of the main plateau which constitutes the flat summit of Table Mountain as seen from the north. From the Southern Suburbs side, the Nursery Ravine and Skeleton Gorge routes start at Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden. The route via Skeleton Gorge to Maclear's Beacon is known as Smuts Track in memory of Jan Smuts, who was a keen hiker. The Bridle Path, or Jeep Track, makes a more gradual ascent from Constantia Nek along the road used to service the dams on Back Table. There are many other paths in popular walking areas on the lower slopes of the mountain accessed from Constantia Nek, Cecilia Park, Kirstenbosch, Newlands Forest and Rhodes Memorial.

There are a number of ascents on the Atlantic side of the mountain, the most popular being Kasteelspoort, a ravine overlooking Camps Bay.

There is a popular "Contour Path" that runs from Constantia Nek, and then, in succession, above Cecilia Park, Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens, Newlands Forest, and from there, above Groote Schuur Estate, past the King's Blockhouse, at the north-east corner of Devil's Peak, immediately below the Mowbray Ridge cliffs, to the front of Devil's Peak and the north face of Table Mountain, ending at the bottom of Kloof Corner Ridge at the western end of the Table Mountain cliffs.[47][48] It starts at Constantia Nek at 250 m and climbs to around 320 m above Cecilia Park and Kirstenbosch, then climbs to 470 m to the scree below the cliffs of Fernwood Buttress. It then descends to 350 m, only to ascend to 400 m 1 km later and remains on this contour until the King's Blockhouse, and from there, eventually, to Tafelberg Road (at 400 m). From the King's Blockhouse it is possible to choose a footpath that will lead to the "upper contour path" which traverses the front (north face) of Devil's Peak and Table Mountain at 500 m, to just beyond the Lower Cable Station. From there it is possible, from either contour path, to join up with the "Pipe Track" which starts from Kloof Nek, and then runs at an elevation of about 300 m, below the cliffs of the Twelve Apostles, on the Atlantic side of the mountain range as far as the Oudekraal Ravine, where the path goes up the ravine to join the "Apostles Path" on top of the Back Table at an elevation of 685 m.[48] There are innumerable paths which join the contour path from below (at least five from Kirstenbosch alone), and somewhat fewer that join it from above.[47][48]

On top of the mountain, and particularly on the Back Table, there is an extensive network of well marked hiking paths over a variety of terrains and distances and durations up to several hours or all day.[47] Maps of all the routes are available at bookshops and outdoor recreation stores, which hikers are advised to use, as dense mist and cold weather (or extreme heat) can descend without warning at any time of the year.

The Hoerikwaggo Trails[49] were four hiking trails on the Cape Peninsula Mountain Chain ranging from two to six days, operated by South African National Parks (SANPARKS) between the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront and Cape Point. Today (2017) the trails can no longer be undertaken with an official SANPARKS guide, and only four of the original accommodation facilities are operational (the Overseer's Cottage on the Back Table, the Orange Kloof Tented Camp, the Slangkop Tented Camp and the Smitswinkel Tented Camp). These camps are "self-catering", each with communal ablution facilities, with large communal kitchen/lounge areas, fully equipped for 12 persons.[50] SANPARKS arranges for luggage and provisions to be transported to the operational cottages and tented camps, so that the hikers can ascend the mountain unencumbered by heavy backpacks. The four Table Mountain Hoerikwaggo hiking trails were called the People's Trail, Table Mountain Trail, Orangekloof Hiking Trail and Top to Tip Trail.[51]

-

Winter ascent of Table Mountain. Hikers set out on one of the many popular trails

-

The plaque at Maclear's beacon at the highest point on Table Mountain (and the Cape Peninsula) at 1084 m. It commemorates Maclear's recalculation of the curvature of the Earth in the Southern Hemisphere. In 1750, Abbé Nicolas Louis de Lacaille had measured the curvature of a meridian arc northwards from Cape Town, to determine the figure of the Earth, and found that the curvature of the Earth was less in southern latitudes than at corresponding northern ones (i.e. that the Earth was slightly pear-shaped, with the wider bulge south of the equator). However, when Sir George Everest visited the Cape in 1820 and inspected the site of La Caille's measurements in Cape Town, he suggested to Maclear that the gravitational effect of Table Mountain could have caused a miscalculation of the curvature of the meridian. This was based on Everest's experience in the Himalayas. Taking this factor into account Maclear established the curvature of the Southern Hemisphere was in fact the same as that of the Northern Hemisphere.

-

Map showing the conservation areas and forests of the eastern slopes of Table Mountain and the Back table. e.g. Cecilia Park, Kirstenbosch, Newlands Forest, and Groote Schuur Estate. The north face of the mountain (Table Mountain flanked by Devil's Peak to the east and Lion's Head to the west, as well as the "Twelve Apostles" on the Atlantic side are also shown.

Rock climbing

[edit]Rock climbing on Table Mountain is a very popular pastime. There are well-documented climbing routes of varying degrees of difficulty up the many faces of the mountain. The main climbs are located on cliffs below the upper cable station. No bolting can be done here and only traditional climbing is allowed. Commercial groups also offer abseiling from the upper cable station.

Caving

[edit]Most of the world's important caves occur in limestone but Table Mountain is unusual in having several large cave systems that have developed in sandstone. The biggest systems are the Wynberg Caves, located on the Back Table, not far from the Jeep Track, in ridges overlooking Orange Kloof and Hout Bay.

Mountain biking

[edit]The slopes of Table Mountain have many jeep tracks that allow mountain biking. The route to the Block House is a popular route for bike riding. Plum Pudding Hill is the name of a very steep jeep track. Bike riders should follow the directional signs on display for mountain bike riders.

"Mensa" constellation

[edit]Table Mountain is the only terrestrial feature to give its name to a constellation: Mensa, meaning The Table. The constellation is seen in the Southern Hemisphere, below Orion, around midnight in mid-July. It was named by the French astronomer Nicolas de Lacaille during his stay at the Cape in the mid-18th century.[52]

Image gallery

[edit]-

Devil's Peak seen from Signal Hill

-

View from Signal Hill with Devil's Peak to the left

-

The "tablecloth" cloud formation over the north face of Table Mountain

-

North face of Table Mountain seen from above the lower cable station.

-

Upper Cable Station from the summit of Lion's Head

-

The cable car with Robben Island in the background

-

Lion's Head as seen from Table Mountain cable car.

-

Cape Town and Table Bay from the slopes of Devil's Peak, showing some of the mountain biking jeep tracks.

-

The concrete part of the Bridle Path—the most gradually-inclined route to the Back Table

-

Time is a Gift, one of several plaques at the top of Table Mountain

-

Warning sign at India Venster, Contour Path, Table Mountain

-

Shop at the Top, Table Mountain

-

Table Mountain and Cape Town seen from Bloubergstrand.

-

View from Milnerton beach

-

View of Table Mountain from Blouberg beach.

-

View of Table Mountain at sunset.

-

As seen from the other side of Table Bay at sunset.

See also

[edit]- Cape Peninsula – Rocky peninsula in the Western Cape, South Africa

- Western Cape – Province of South Africa

- Cape Fold Mountains – Paleozoic fold and thrust belt in South Africa

- Devil's Peak – Mountain peak in Cape Town, South Africa

- Lion's Head – Mountain in Cape Town, South Africa

- Mesa – Elevated area of land with a flat top and sides, usually much wider than buttes

- Table Mountain National Park – A nature conservation area on the Cape Peninsula in Cape Town, South Africa

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ In 2011–2012 dassies began to be seen in Bakoven, on the Atlantic coast, below the Twelve Apostles Mountains. They were then seen in the Silvermine region of the Table Mountain National Park, and in 2015 at the restaurant on the top of the western end of Table Mountain, as well as elsewhere in the mountains. But even in 2017 dassies are still not as abundant as they were on the Peninsula Mountain Chain in the 1990s.

References

[edit]- ^ Google Maps showing a section including Devils' Peak and Lion's Head, with a scale at lower rim Archived 24 April 2024 at the Wayback Machine, obtained 24 April 2024

- ^ 3318CD Cape Town (Map) (9th ed.). 1:50,000. Topographical. Chief Directorate: National Geo-spatial Information. 2000.

- ^ "World Ribus – Southern Africa". World Ribus. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Table Mountain in Cape Town". vibescout.com. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "33 cool facts about Table Mountain". news.uct.ac.za. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ "15 Things You Didn't Know About Table Mountain". 2017. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ "Table Mountain". BootsnAll Travel. December 2002. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- ^ "Cape Town Info". Archived from the original on 15 October 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Compton, John S. (2004) The Rocks & Mountains of Cape Town. Cape Town: Double Story. ISBN 978-1-919930-70-1

- ^ McCarthy, T.; Rubidge, B. (2005). The Story of Earth and Life. Cape Town: Struik. pp. 188–192. ISBN 1-77007-148-2.

- ^ a b Tankard, A. J.; Jackson, M. P. A.; Eriksson, K. A.; Hobday, D. K.; Hunter, D. R.; Minter, W. E. L. (1982). Crustal Evolution of Southern Africa. 3.8 Billion Years of Earth' History. New York: Springer. pp. 338–344. ISBN 0-387-90608-8.

- ^ "Geology of the Cape Peninsula". UCT Department of Geological Sciences. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2006.

- ^ "The Geology of Table Mountain". CapeConnected. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2006.

- ^ a b Manning, John (2007). "Cone Bush, Tolbos". In: Field Guide to Fynbos. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. p. 258. ISBN 9781770072657.

- ^ "IDM Cape Peninsula - Ld arge". www.proteaatlas.org.za. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ a b Trinder-Smith, Terry (2006). "Orchidaceae". In: Wild Flowers of the Table Mountain National Park. Kirstenbosch, Claremont: Botanical Society of South Africa. pp. 104–105. ISBN 1874999600.

- ^ a b c d e Manning, John (2007). "The World of Fynbos". In: Field Guide to Fynbos. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. pp. 8–23. ISBN 9781770072657.

- ^ a b Trinder-Smith, Terry (2006). "Introduction". In: Wild Flowers of the Table Mountain National Park. Cape Town: Botanical Society of South Africa. pp. 19–35. ISBN 1874999600.

- ^ Manning, John (2007). "Disa". In: Field Guide to Fynbos. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. pp. 162–163. ISBN 9781770072657.

- ^ a b Sleigh, Dan (2002). Islands. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 429. ISBN 0436206323.

- ^ Bond, William J. (1996). Fire and Plants. London: Chapman and Hall.

- ^ a b Kraaij, Tineke; van Wilgen, Brian W. (2014). "Drivers, ecology, and management of fynbos fires.". In Allsopp, Nicky; Colville, Jonathan F.; Verboom, G. Anthony (eds.). Fynbos, Ecology, Evolution and Conservation of a Megadiverse Region. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780199679584.

- ^ a b c d Pauw, Anton; Johnson, Steven (1999). "The Power of Fire". in: Table Mountain. Vlaeberg, South Africa: Fernwood Press. pp. 37–53. ISBN 1-874950-43-1.

- ^ Saunders, Christopher; Bundy, Colin, eds. (1992). "A way of life perfected". Reader's Digest Illustrated History of South Africa. Cape Town: Reader’s Digest Association Ltd. pp. 20–25. ISBN 0-947008-90-X.

- ^ a b c d Maytham Kid, Mary (1983). "Introduction". In: Cape Peninsula. South African Wild Flower Guide 3. Kirstenbosch, Claremont: Botanical Society of South Africa. p. 27. ISBN 0620067454.

- ^ "Perceval" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2012.

- ^ "Brochures, booklets and posters". Capetown.gov.za. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ Pooley, Simon (2014). Burning Table Mountain: an environmental history of fire on the Cape Peninsula. London / Cape Town: Palgrave / UCT Press. pp. 162–183. ISBN 978-1-349-49059-2.

- ^ Information gleaned from reports in the Cape Bird Club's newsletters from the 1950s onwards

- ^ Jenkins, A.R.; van Zyl, A.J. (2005). "Conservation status and community structure of cliff-nesting raptors and ravens on the Cape Peninsula, South Africa". Ostrich. 76 (3–4): 175–184. Bibcode:2005Ostri..76..175J. doi:10.2989/00306520509485490. ISSN 0030-6525. S2CID 84239150.

- ^ a b Hockey, P. A. R.; Dean, W. R. J.; Ryan, P. G., eds. (2005). Roberts Birds of Southern Africa (Seventh ed.). Cape Town: John Voelcker Bird Book Fund. pp. 531–532. ISBN 0-620-34053-3.

- ^ Jenkins, Andrew; van Zyl, Anthony (2002). "Home on the range. Raptor riches of the Cape Peninsula". Africa Birds & Birding. 7: 38–46.

- ^ Cape Peninsula Baboon Research Unit Archived 11 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Managing baboon-human conflict: City of Cape Town – Case Studies- NCC Environmental Services". ncc-group.co.za. 22 January 2020. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ "The Quagga Project". The Quagga Project. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ van Sitters, Bradley (2 August 2012). "Place Names of Pre-colonial Origin and their Use Today". The Archival Platform. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Nienaber, Gabriel Stefanus; Raper, PE (1983). Hottentot (Khoekhoen) Place Names. Onomastic Research Centre, Human Sciences Research Council. ISBN 9780409104219.

- ^ "The First British Occupation (1795–1803)". The Fortress Study Group. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ^ "Kings Block House". Cape of Good Hope Living Heritage. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ^ "THE BATTLE OF BLAAUWBERG – 200 YEARS AGO". Military History Journal. 13 (4). The South African Military History Society. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Pooley, Simon (2014). Burning Table Mountain: an environmental history of the Cape Peninsula. London / Cape Town: Palgrave / UCT Press. pp. 135–161. ISBN 978-1-349-49059-2.

- ^ Pooley, Simon (6 March 2015). "Independent Online". Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017 – via Google.

- ^ "Table Mountain fire 'burns out of control' in Cape Town". BBC News. 18 April 2021. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "The Provisional New 7 Wonders of Nature". new7wonders.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "Table Mountain Aerial Cableway Company". Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ "Bleichert Passenger Cable Way Order Book: Order November 16, 1926 – Exhibit No.3013"

- ^ a b c Slingsby, Peter (2010). Table Mountain, the map. Muizenberg: Baardskeerder. ISBN 978-1-920377-10-6.

- ^ a b c Clarke, Hugh; Mackenzie, Bruce (2007). Common wild flowers of Table Mountain. Cape Town: Struik Publications. pp. 12–13, 96–98. ISBN 978-1-77007-383-8.

- ^ "Hoerikwaggo Trails". SANParks. Archived from the original on 17 February 2006. Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- ^ "Hoerikwaggo Tented Camps". Table Mountain National Park. Archived from the original on 2 April 2006. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ "Table Mountain Trails". Cape Town Direct. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- ^ Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars. McDonald & Woodward. p. 207. ISBN 0-939923-78-5.