Thrombopoietin

Thrombopoietin (THPO) also known as megakaryocyte growth and development factor (MGDF) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the THPO gene.

Thrombopoietin is a glycoprotein hormone produced by the liver and kidney which regulates the production of platelets. It stimulates the production and differentiation of megakaryocytes, the bone marrow cells that bud off large numbers of platelets.[5]

Megakaryocytopoiesis is the cellular development process that leads to platelet production. The protein encoded by this gene is a humoral growth factor necessary for megakaryocyte proliferation and maturation, as well as for thrombopoiesis. This protein is the ligand for MLP/C_MPL, the product of myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene.[6]

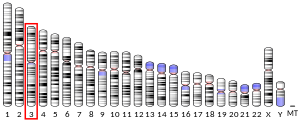

Genetics

[edit]The thrombopoietin gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 3 (q26.3-27). Abnormalities in this gene occur in some hereditary forms of thrombocytosis (high platelet count) and in some cases of leukemia. The first 155 amino acids of the protein share homology with erythropoietin.[7]

Function and regulation

[edit]Thrombopoietin is produced in the liver by both parenchymal cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells, as well as in the kidney by proximal convoluted tubule cells. Small amounts are also made by striated muscle and bone marrow stromal cells.[5] In the liver, its production is augmented by interleukin 6 (IL-6).[5] However, the liver and the kidney are the primary sites of thrombopoietin production.

Thrombopoietin regulates the differentiation of megakaryocytes and platelets, but studies on the removal of the thrombopoietin receptor show that its effects on hematopoiesis are more versatile.[5]

Its negative feedback is different from that of most hormones in endocrinology: The effector regulates the hormone directly. Thrombopoietin is bound to the surface of platelets and megakaryocytes by the mpl receptor (CD 110). Inside the platelets it gets destroyed, while inside the megakaryocytes it gives the signal of their maturation and consecutively more platelet production. The bounding of the hormone at these cells thereby reduces further megakaryocyte exposure to the hormone.[5] Therefore, the rising and dropping platelet and megakaryocyte concentrations regulate the thrombopoietin levels. Low platelets and megakaryocytes lead a higher degree of thrombopoietin exposure to the undifferentiated bone marrow cells, leading to differentiation into megakaryocytes and further maturation of these cells. On the other hand, high platelet and megakaryocyte concentrations lead to more thrombopoetin destruction and thus less availability of thrombopoietin to bone marrow.

TPO, like EPO, plays a role in brain development. It promotes apoptosis of newly generated neurons, an effect counteracted by EPO and neurotrophins.[8]

Therapeutic use

[edit]Despite numerous trials, thrombopoietin has not been found to be useful therapeutically. Theoretical uses include the procurement of platelets for donation,[9] and recovery of platelet counts after myelosuppressive chemotherapy.[5]

Trials of a modified recombinant form, megakaryocyte growth and differentiation factor (MGDF), were stopped when healthy volunteers developed autoantibodies to endogenous thrombopoietin and then developed thrombocytopenia.[10] Romiplostim and Eltrombopag, structurally different compounds that stimulate the same pathway, are used instead.[11]

A quadrivalent peptide analogue is being investigated, as well as several small-molecule agents,[5] and several non-peptide ligands of c-Mpl, which act as thrombopoietin analogues.[12][13]

Discovery

[edit]Thrombopoietin was cloned by five independent teams in 1994. Before its identification, its function has been hypothesized for as much as 30 years as being linked to the cell surface receptor c-Mpl, and in older publications thrombopoietin is described as c-Mpl ligand (the agent that binds to the c-Mpl molecule). Thrombopoietin is one of the Class I hematopoietic cytokines.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000090534 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022847 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kaushansky K (May 2006). "Lineage-specific hematopoietic growth factors". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (19): 2034–45. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052706. PMID 16687716.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: THPO thrombopoietin (myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene ligand, megakaryocyte growth and development factor)".

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 600044

- ^ Ehrenreich H, Hasselblatt M, Knerlich F, von Ahsen N, Jacob S, Sperling S, et al. (January 2005). "A hematopoietic growth factor, thrombopoietin, has a proapoptotic role in the brain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (3): 862–7. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102..862E. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406008102. PMC 545528. PMID 15642952.

- ^ Kuter DJ, Goodnough LT, Romo J, DiPersio J, Peterson R, Tomita D, et al. (September 2001). "Thrombopoietin therapy increases platelet yields in healthy platelet donors". Blood. 98 (5): 1339–45. doi:10.1182/blood.V98.5.1339. PMID 11520780. S2CID 12119556.

- ^ Li J, Yang C, Xia Y, Bertino A, Glaspy J, Roberts M, Kuter DJ (December 2001). "Thrombocytopenia caused by the development of antibodies to thrombopoietin". Blood. 98 (12): 3241–8. doi:10.1182/blood.V98.12.3241. PMID 11719360.

- ^ Imbach P, Crowther M (August 2011). "Thrombopoietin-receptor agonists for primary immune thrombocytopenia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (8): 734–41. doi:10.1056/NEJMct1014202. PMID 21864167.

- ^ Nakamura T, Miyakawa Y, Miyamura A, Yamane A, Suzuki H, Ito M, et al. (June 2006). "A novel nonpeptidyl human c-Mpl activator stimulates human megakaryopoiesis and thrombopoiesis". Blood. 107 (11): 4300–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-11-4433. PMID 16484588.

- ^ Jenkins JM, Williams D, Deng Y, Uhl J, Kitchen V, Collins D, Erickson-Miller CL (June 2007). "Phase 1 clinical study of eltrombopag, an oral, nonpeptide thrombopoietin receptor agonist". Blood. 109 (11): 4739–41. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-11-057968. PMID 17327409.

Further reading

[edit]- Hitchcock IS, Kaushansky K (April 2014). "Thrombopoietin from beginning to end". British Journal of Haematology. 165 (2): 259–68. doi:10.1111/bjh.12772. PMID 24499199. S2CID 39360961.

- Wörmann B (October 2013). "Clinical indications for thrombopoietin and thrombopoietin-receptor agonists". Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy. 40 (5): 319–25. doi:10.1159/000355006. PMC 3822275. PMID 24273485.

- Kuter DJ (July 2013). "The biology of thrombopoietin and thrombopoietin receptor agonists". International Journal of Hematology. 98 (1): 10–23. doi:10.1007/s12185-013-1382-0. PMID 23821332.

- Lupia E, Goffi A, Bosco O, Montrucchio G (2012). "Thrombopoietin as biomarker and mediator of cardiovascular damage in critical diseases". Mediators of Inflammation. 2012: 390892. doi:10.1155/2012/390892. PMC 3337636. PMID 22577249.

- Liebman HA, Pullarkat V (2011). "Diagnosis and management of immune thrombocytopenia in the era of thrombopoietin mimetics" (PDF). Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2011: 384–90. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.384. PMID 22160062.