Turkish Airlines Flight 1951

The wreckage of the Boeing 737 after the crash | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 25 February 2009 |

| Summary | Stalled and crashed on landing due to faulty radio altimeter and pilot error[1][2][3][4][5] |

| Site | North of the Polderbaan runway (18R/36L), near Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, Amsterdam, Netherlands 52°22′34″N 4°42′50″E / 52.37611°N 4.71389°E |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 737-8F2 |

| Aircraft name | Tekirdağ |

| Operator | Turkish Airlines |

| IATA flight No. | TK1951 |

| ICAO flight No. | THY1951 |

| Call sign | TURKISH 1951 |

| Registration | TC-JGE |

| Flight origin | Istanbul Atatürk Airport, Istanbul, Turkey |

| Destination | Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Occupants | 135 |

| Passengers | 128 |

| Crew | 7 |

| Fatalities | 9 |

| Injuries | 125 |

| Survivors | 126 |

Turkish Airlines Flight 1951 (also known as the Poldercrash[6] or the Schiphol Polderbaan incident) was a passenger flight that crashed during landing at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, the Netherlands, on 25 February 2009, resulting in the deaths of nine passengers and crew, including all three pilots.

The aircraft, a Turkish Airlines Boeing 737-800, crashed into a field about 1.5 km (0.9 mi) north of the Polderbaan runway (18R), prior to crossing the A9 motorway inbound, at 09:26 UTC (10:26 CET), having flown from Istanbul, Turkey. The aircraft broke into three pieces on impact. The wreckage did not catch fire.[7][8][9]

The crash was caused primarily by the aircraft's automated reaction, which was triggered by a faulty radio altimeter. This caused the autothrottle to decrease the engine power to idle during approach. The crew noticed this too late to take appropriate action to increase the thrust and recover the aircraft before it stalled and crashed.[10] Boeing has since issued a bulletin to remind pilots of all 737 series and BBJ aircraft of the importance of monitoring airspeed and altitude, advising against the use of autopilot or autothrottle while landing in cases of radio altimeter discrepancies.[11]

A 2020 investigation by The New York Times found that the Dutch investigation into the crash "either excluded or played down criticisms" of Boeing following pressure from Boeing and US federal safety officials, who instead "emphasized pilot error as a factor ... rather than design flaws."[12]

Background

[edit]Aircraft

[edit]The aircraft operating Flight 1951 was a 7-year-old Next Generation Boeing 737-800 series model 8F2[13] with registration TC-JGE, named "Tekirdağ".[14][15] Model 8F2 denotes the configuration of the 737-800 built for use by Turkish Airlines. It had 51 aircraft of this model in service at the time of the crash.[16] The aircraft made its first flight on 24 January 2002 and was delivered to Turkish Airlines on March 27.

Flight

[edit]

On board were 128 passengers and seven crew members.[14][17][18] The flight was under the command of Instructor Captain Hasan Tahsin Arisen (age 54).[19] A former Turkish Air Force fleet commander, Captain Arisen had been working for Turkish Airlines since 1996 and was one of the most experienced pilots at the airline.[20] He had over 5,000 hours of flight time on the F-4E Phantom II.[20] Olgay Özgür (age 28) was the safety pilot of the flight, a graduate of a flight school in Ankara, who flew the MD-80 for World Focus Airlines before joining Turkish Airlines and passing the 737 type rating in 2006; he was sitting in the cockpit's center jump seat. Murat Sezer (42), co-pilot under line training, was flying as co-pilot.[21] The cabin crew consisted of Figen Eren, Perihan Özden, Ulvi Murat Eskin, and Yasemin Vural.[22]

Accident

[edit]

The flight was cleared for an approach on runway 18R (also known as the Polderbaan runway), but came down short of the runway threshold, sliding through the wet clay of a plowed field.

The aircraft suffered significant damage. Although the fuselage broke into three pieces, it did not catch fire. Both engines separated and came to rest 100 m (330 ft) from the fuselage.[23]

While several survivors and witnesses indicated that rescuers took 20 to 30 minutes to arrive at the site after the crash,[24][25] others have stated that the rescuers arrived quickly at the scene.[24][26][27] About 60 ambulances arrived along with at least three LifeLiner helicopters (air ambulances, Eurocopter EC135), and a fleet of fire engines.[citation needed] An unconfirmed report by De Telegraaf states that the firefighters were at first given the wrong location for the crash site, delaying their arrival.[28] Lanes of the A4 and A9 motorways were closed to all traffic to allow emergency services to quickly reach the site of the crash.

The bodies of the three cockpit crew members were the last to be removed from the plane, around 20:00 that evening, because the cockpit had to be examined before it could be cut open to get to these crew members.[29] Some of the survivors said that one of the pilots was alive after the crash.[30] The relatives of the passengers on the flight were sent to Amsterdam by Turkish Airlines shortly afterward.[31]

All flights in and out of Schiphol Airport were suspended, according to an airport spokeswoman. Several planes were diverted to Rotterdam The Hague Airport and to Brussels Airport. Around 11:15 UTC (12:15 CET), the Kaagbaan runway (06/24) was reported to have been reopened to air traffic, followed by the Buitenveldertbaan runway (09/27).[32]

Turkish Airlines continues to use the flight number 1951 on its Istanbul-to-Amsterdam route, primarily operated by an Airbus A321neo and an Airbus A330.[33]

TC-JMJ, an Airbus A321 delivered two days after the accident to Turkish Airlines was named Tekirdağ in memory of the flight.[34]

Investigation

[edit]The investigation was led by the Dutch Safety Board (DSB, Dutch: Onderzoeksraad voor Veiligheid or OVV), and assisted by an expert team from Turkish Airlines and a representative team of the American National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), accompanied by advisors from Boeing and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA),[35][36] Turkish Directorate General of Civil Aviation (SHGM), the operator, the UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch, and the French Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (BEA).[11][37] The cockpit voice recorder and the flight data recorder were recovered quickly after the crash, after which they were transported to Paris to read out the data.[38] The Dutch public prosecution service initially asked the DSB to hand over the black boxes, but the DSB refused to do so. It stated that no indication of homicide, manslaughter, hijacking, or terrorism was present, which would warrant an investigation by the prosecution.[39][40]

While on final approach for landing, the aircraft was about 2,000 ft (610 m) above ground, when the left-hand (captain's) radio altimeter suddenly changed from 1,950 feet (590 m) to read −8 feet (−2.4 m) altitude, although the right-hand (co-pilot's) radio altimeter functioned correctly.[10] The voice recording showed that the crew was given an audible warning signal (landing gear warning horn) that indicated that the aircraft's landing gear should be down, as the aircraft was, according to the captain's radio altimeter, flying too low. This happened several times during the approach to Schiphol. The reason that the captain's radio altimeter was causing problems was the first officer making a mistake when arming the aircraft's autopilot system for a dual channel ILS (Instrument Landing System) approach.

The Boeing 737NG has two autopilot systems or flight control units (FCU), which can work independently of each other (single channel) or together (dual channel). These systems are called CMD A and CMD B. CMD A is the left seat FCU (Captain), while CMD B is the right seat FCU (First Officer). During normal operations, the PF (Pilot flying) uses their respective FCU. This is referred to as "single channel". However if the crew intended to fly an auto-land, which is when the airplane flies the approach and landing itself (During a CAT III ILS Approach), one would engage both FCUs, this way the approach can be flown to greater precision in bad visibility, allowing the pilots to lower the MDA (Minimum decision altitude) to 50 ft. this is called a "dual channel". Turkish Airlines' standard operating procedure at the time stated that all approaches should be flown "dual channel" when available, but the inexperienced (on the 737NG) first officer forgot to arm approach mode in the aircraft's mode control panel (MCP) before he engaged CMD A to make the approach "dual channel", meaning that the aircraft thought the pilots wanted to do a single-channel approach using CMD A (captain's autopilot) only. However unbeknownst to the pilots CMD A had a radio altimeter fail, which would be the main contributor to the accident.[10] Later, the safety board's preliminary report indicated that the flight data recorder history of the captain's radio altimeter showed 8191 feet (the maximum possible recorded) until the aircraft descended through 1950, then suddenly showed negative 8 feet.[41]

The throttles were pulled back to idle thrust to slow the aircraft to descend and acquire the glideslope, but the autothrottle unexpectedly reverted to "retard" mode, which is designed to automatically decrease thrust shortly before touching down on the runway at 27 ft (8.2 m) above runway altitude.[42] At 144 knots (267 km/h; 166 mph), the pilots manually increased thrust to sustain that speed,[41] but the autothrottle immediately returned the thrust lever to idle power because the first officer did not hold the throttle lever in position. The throttles remained at idle for about 100 seconds while the aircraft slowed to 83 knots (154 km/h; 96 mph), 40 knots (74 km/h; 46 mph) below reference speed as the aircraft descended below the required altitude to stay on the glideslope.[43] The stick-shaker activated about 150 m (490 ft) above the ground, indicating an imminent stall, the autothrottle advanced, and the captain attempted to apply full power.[43] The engines responded, but not enough altitude or forward airspeed was available to recover, and the aircraft hit the ground tail first at 95 knots (176 km/h; 109 mph).[43]

The data from the flight recorder also showed that the same altimeter problem had happened twice during the previous eight landings, but that on both occasions, the crew had taken the correct action by disengaging the autothrottle and manually increasing the thrust. Investigations are under way to determine why more action had not been taken after the altimeter problem was detected.[44] In response to the preliminary conclusions, Boeing issued a bulletin, Multi-Operator Message (MOM) 09-0063-01B, to remind pilots of all 737 series and Boeing Business Jet (BBJ) aircraft of the importance of monitoring airspeed and altitude (the "primary flight instruments"), advising against the use of autopilot or autothrottle while landing in cases of radio altimeter discrepancies.[11] Following the release of the preliminary report, Dutch and international press concluded that pilot inattention caused the accident,[45][46][47][48] though several Turkish news publications still emphasized other possible causes.[49][50]

On 9 March 2009, the recovery of the wreckage started. All parts of the plane were moved to an East Schiphol hangar[51][52] for reconstruction.[failed verification]

It was reported that the first officer survived the crash itself, but that rescuers were unable to reach him via the cockpit door, owing to security measures introduced in the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks. The rescuers eventually cut their way into the cockpit through the roof, by which time the first officer had died.[53]

The final report was released on 6 May 2010. The DSB stated that the approach was not stabilized; hence, the crew ought to have initiated a go-around. The autopilot followed the glide slope, while the autothrottle reduced thrust to idle, owing to a faulty radio altimeter showing an incorrect altitude. This caused the airspeed to drop and the pitch attitude to increase; all this went unnoticed by the crew until the stick-shaker activated. Prior to this, air traffic control caused the crew to intercept the glide slope from above; this obscured the erroneous autothrottle mode and increased the crew's workload. The subsequent approach to stall recovery procedure was not executed properly, causing the aircraft to stall and crash.[54] Turkish Airlines disputed the crash inquiry findings on stall recovery.[55]

Passengers

[edit]| Nationality [56][57][58][59][60] |

Passengers | Crew | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Killed | Survived | Total | Killed | Survived | Total | Killed | Survived | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 53 | 0 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53 | 0 | 53 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 51 | 1 | 50 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 58 | 5 | 53 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 3 | |

| Total | 118 | 5 | 113 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 125 | 9 | 116 |

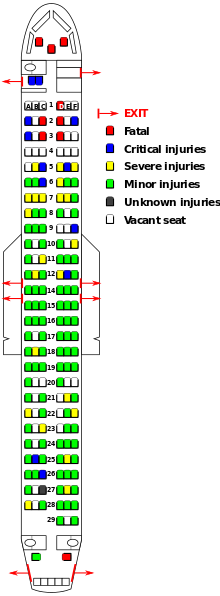

Nine fatalities and a total of 120 injuries occurred, with 11 of them serious.[54]: 29, 178–180 Five of the deceased were Turkish citizens, including the captain, the first officer, a line -training pilot, and one member of the cabin crew.[61][62][63][64] Four were Americans, of whom three have been identified as Boeing employees stationed in Ankara and working on an Airborne Early Warning and Control program for the Turkish military.[7][17][52][58][59]

The plane carried 53 passengers from the Netherlands, 51 from Turkey, 7 from the United States, 3 from the United Kingdom, 1 each from Germany, Bulgaria, Italy, and Taiwan.[56][57][58][59][60]

Confidential information onboard

[edit]Following media speculation, a spokesperson for the prosecutor's office in Haarlem confirmed in April 2009 to Agence France-Presse that instructions were given following the crash to remove four Boeing laptops from the wreckage, and that the laptops were handed over to the US embassy in The Hague.[65][66] According to Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf, the Boeing employees on board were in possession of confidential military information.[67][68]

Turkish media outlets Radikal and Sözcü also reported that the Boeing employees on board were in possession of confidential military information, and that the rescue response was delayed because American officials had specifically requested from Dutch authorities that no one was to approach the wreckage until after the confidential information was retrieved.[69][70]

According to Radikal, the then-CEO of Turkish Airlines, Temel Kotil, had also stated that a Turkish Airlines employee stationed at Schiphol Airport had arrived at the crash site with his apron-access airport identification, but was prevented from reaching the wreckage, and was handcuffed and detained by Dutch authorities after resisting.[69][70]

While the De Telegraaf article and some Turkish sources allege that U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation or Central Intelligence Agency agents were on-site for recovery, this was denied by the prosecutor's office.[71]

Boeing and NTSB pushback

[edit]An investigation by The New York Times' Chris Hamby published in January 2020 in the aftermath of the Boeing 737 MAX groundings claimed that the DSB "either excluded or played down criticisms of the manufacturer in its 2010 final report after pushback from a team of Americans that included Boeing and federal safety officials...who said that certain pilot errors had not been 'properly emphasized'".[12] The Hamby article draws on a 2009 human factors analysis by Sidney Dekker, which was not published publicly by the DSB until after The New York Times investigation was published.[72][73]

In February 2020, it was reported that Boeing had refused to cooperate with a new Dutch review on the crash investigation and that the NTSB had also refused a request from Dutch lawmakers to participate.[73]

In media

[edit]The Discovery Channel Canada / National Geographic TV series Mayday featured the crash and investigation in a season-10 episode titled "Who's in Control?".[74]

The episode is dramatized in the episode "Who’s Flying" of Why Planes Crash.

Gallery

[edit]-

The full crash site of Turkish Airlines Flight 1951

-

Both jet engines separated, coming to rest 100 m (330 ft) from the fuselage

-

Rescuers at the scene

-

The left wing of the aircraft

-

Temporary memorial near the crash site

References

[edit]- ^ Toby Sterling (6 May 2010). "Tech problem, pilots caused Turkish Airlines crash". Bloomberg Businessweek. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010.

A common malfunction with Boeing radio altimeters, compounded by several errors by pilots, led to last year's fatal crash by a Turkish Airlines plane as it dropped short of the runway at Amsterdam's airport, according to investigators' final report released Thursday.

- ^ RNW News and Peter van Beem (4 March 2009). "Faulty altimeter caused airline crash". Radio Netherlands. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009.

- ^ "Altimeter fault behind Turkish Airlines crash". AFP. 5 March 2009. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011.

- ^ "Dutch investigators determine cause of Turkish airlines crash". Deutsche Welle. 5 March 2009. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009.

Investigators found that a faulty altimeter caused the plane's autopilot to shut down the engines as it made its approach to land

- ^ "Faulty altimeter contributed to Turkish Airlines crash: officials". CBC News. 4 March 2009.

According to recorded conversation involving the plane's captain, first officer and an apprentice pilot in the cockpit, the faulty altimeter was noticed but wasn't considered a problem.

- ^ "Eindrapportage Poldercrash" [Final report Polder crash]. www.rijksoverheid.nl (in Dutch). Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Turkish plane crashes at Amsterdam airport". CNN. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ "Turkish plane crash in Amsterdam". BBC News. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ Hradecky, Simon. "Accident: Turkish Airlines B738 at Amsterdam on Feb 25th 2009, landed on a field". The Aviation Herald.

- ^ a b c "Press Statement on first findings, 4 March 2009" (PDF) (in Dutch). Dutch Safety Board. 4 March 2009., official translation from "[Press statement on first findings]" (PDF) (in Dutch). Dutch Safety Board. 4 March 2009.

- ^ a b c Fiorino, Frances (5 March 2009). "Boeing warns of possible 737 altimeter fault". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012.

- ^ a b Hamby, Chris (20 January 2020). "How Boeing's Responsibility in a Deadly Crash 'Got Buried'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ "25 FEB 2009 Boeing 737-8F2". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Accident Information Page". Turkish Airlines. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ "Aircraft TC-JGE Profile". AirportData.com. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ "Fleet Data Turkish Airlines". Turkish Airlines. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009.

- ^ a b "Vijf Turken en vier Amerikanen omgekomen bij crash" [Five Turks and four Americans died in crash] (in Dutch). TC/Tubantia. Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau. 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ Final report, section 2.4 "History of the flight", p.25

- ^ wires, Hurriyet DN Online with (27 February 2009). "Turkish Airlines names four dead crew members in Amsterdam crash". www.hurriyet.com.tr.

- ^ a b Brothers, Caroline; Arsu, Sebnem (25 February 2009). "At least 9 killed as Turkish plane crashes near Amsterdam". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ "Dutch Safety Board report" (PDF).

- ^ "Turkish Airlines names four dead crew members in Amsterdam crash". www.hurriyet.com.tr. 27 February 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Brothers, Caroline; Arsu, Sebnem (25 February 2009). "9 killed as Turkish plane crashes near Amsterdam". International Herald Tribune. Paris: The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Kranten staan uitgebreid stil bij crash" [Newspapers extensively discuss the crash] (in Dutch). fok.nl. 26 February 2009.

- ^ "Kazadan kurtulan yolcular olayı anlattı" [Passengers who survived the accident told about the incident] (in Turkish). 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 13 July 2009.

- ^ "How the Schiphol crash happened". BBC News. 25 February 2009.

Helpers arrived at the scene very quickly and gave first aid on the spot

- ^ "Turkish Airlines plane crashes near Schiphol – 5th Update". 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013.

- ^ "Boeing 737 Crasht Bij Schiphol" [Boeing 737 crashes at Schiphol]. De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 25 February 2009.

- ^ "Crash B-737-800 Turkish Airlines, Schiphol Amsterdam killing at least 9". Aviation News EU. 25 February 2009.

- ^ "Ürperten iddia: Pilot yaşıyordu, zamanında yardım edilmediği için hayatını kaybetti" [Chilling claim: The pilot was alive, but he died because he was not helped in time]. Zaman Newspaper (Turkish). 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 28 April 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ "Vliegtuig met familieleden gearriveerd" [Plane with family members arrived] (in Dutch). nu.nl. 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- ^ "Negen doden bij vliegtuigcrash Schiphol" [Nine dead in Schiphol plane crash] (in Dutch). Volkskrant. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- ^ "Flight history for Turkish Airlines flight TK1951". Flightradar24. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ "THY Turkish Airlines TC-JMJ (Airbus A321 - MSN 3688) | Airfleets aviation".

- ^ "Hollanda'da THY uçağı yere çakıldı" (in Turkish). Radikal. 26 February 2009.

- ^ "NTSB sends team to Amsterdam to assist with 737 aircraft accident investigation" (Press release). National Transportation Safety Board. 25 February 2009.

- ^ "Onderzoeksraad start onderzoek crash Turkish Airlines op Schiphol" (in Dutch). 25 February 2009.

- ^ "Het wachten is op de zwarte doos". de Volkskrant. 27 February 2009.

Maar wat de crash nu écht heeft veroorzaakt, zal mogelijk pas blijken als de zwarte doos is uitgelezen in Parijs, bij het Bureau d'Enquêtes et Analyses (BEA).

- ^ "Van Vollenhoven geeft zwarte dozen niet af" (in Dutch). NRC Handelsblad. 28 February 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

Alleen wanneer er sprake is van „moord, doodslag, gijzeling of terrorisme" is de onderzoeksraad, volgens Van Vollenhoven, verplicht om dat te melden bij het OM. Dat is vooralsnog niet het geval en het OM krijgt de gevraagde gegevens niet, zo maakte Van Vollenhoven duidelijk in het tv-programma Nova

- ^ "Google translation of NRC Handelsblad story". NRC Handelsblad. 28 February 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b "Preliminary Report: Turkish Airlines Flight 1951" (PDF). The Dutch Safety Board. 28 April 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- ^ "Automatic flight – system description: Automatic Flight Approach and Landing". 737 flight crew operations manual. The Boeing Company. 27 September 2004. Section 4.20.14

- ^ a b c Kaminski-Morrow, David (4 March 2009). "Crashed Turkish 737's thrust fell after sudden altimeter step-change". Flight Global.

- ^ "Faulty altimeter played part in Turkish crash". Reuters. 4 March 2009.

- ^ "Piloten Turkish Airlines grepen te laat in" [Turkish Airlines pilots intervened too late] (in Dutch). Trouw. 4 March 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "Boeing issues reminder after Netherlands crash". ABC News. 4 March 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ Bremner, Charles (5 March 2009). "Turkish Airlines pilots ignored faulty altimeter before Amsterdam crash". The Times. London. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "Schiphol airliner crash blamed on altimeter failure, pilot error". Wikinews. 5 March 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "Dutch explanations on plane crash raise more questions than answers". Today's Zaman. 6 March 2009. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "Oh, the humanity". Sabah. 6 March 2009. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "Dutch remove Turkish plane wreckage: Dutch experts started the work to remove the wreckage of the Turkish plane which crashed in Amsterdam, killing nine". World Bulletin. 9 March 2009. Archived from the original on 28 April 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ a b "Turkish Airlines plane wreckage to be removed – The wreckage will be taken to a hangar in East Schiphol". Radio Netherlands. 9 March 2009. Archived from the original on 7 June 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ "Schiphol crash pilot's death draws cockpit door scrutiny". Flight Global. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ a b van Vollenhoven, Pieter; et al. (6 May 2010). "Crashed during approach, Boeing 737-800, near Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, 25 February 2009" (PDF). The Dutch Safety Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Kaminski-Morrow, David (7 May 2010). "Turkish Airlines disputes crash inquiry findings on stall recovery". Archived from the original on 23 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Passenger List". Turkish Airlines. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ a b "6 doden en 4 gewonden niet geïndentificeerd" [6 dead and 4 injured not identified] (in Dutch). Trouw. 26 February 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ a b c "Status of All Four Boeing Employees Confirmed in Amsterdam Accident". Boeing. 28 February 2009.

- ^ a b c Wallace, James (27 February 2009). "Boeing confirms three employees died on airliner: another hospitalized with serious injuries". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ^ a b "5 Turks, 4 Americans among dead in Dutch crash". Yahoo. Associated Press. 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ "Turkey plane crashes in Amsterdam". BBC News. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ "Laatste eer aan bemanningsleden Turkish Airlines" [Last respects to Turkish Airlines crew members] (in Dutch). 28 February 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ "Nine killed as Turkish plane crashes at Amsterdam – Summary". Earth Times. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ "Geen onervaren piloot in verongelukt toestel" [No inexperienced pilot in crashed aircraft] (in Dutch). Nu.nl, Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau. 26 February 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ AFP (10 April 2009). "Laptops in Turkish plane crash said to contain US military secrets". www.hurriyet.com.tr. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ "Secrets militaires américains retirés de l'avion à Amsterdam" [US military secrets removed from plane in Amsterdam]. RTBF Info (in French). 10 April 2009. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ "Schiphol-Absturz: FBI-Trupp soll Geheim-Laptops aus Flugzeugwrack geborgen haben" [Schiphol crash: FBI team is said to have recovered secret laptops from the plane wreckage]. Der Spiegel (in German). 10 April 2009. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Öztürk, Ünal (11 April 2009). "Düşen THY uçağında askeri sırlar vardı" [There were military secrets in the crashed THY plane]. www.hurriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ a b Ataklı, Can (22 April 2009). "FBI düşen THY uçağına 40 dakika kimseyi yaklaştırmadı" [FBI did not let anyone near the crashed THY plane for 40 minutes]. Radikal (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ a b Özdil, Yılmaz (17 December 2019). "Kürecik" [Globule]. www.sozcu.com.tr (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ "FBI'dan Türkiyeye terbiyesizlik!" [Impoliteness from the FBI to Turkey!]. Internet Haber (in Turkish). 23 April 2009. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Dekker, Sidney (2 July 2009). "Report of the Flight Crew Human Factors Investigation Conducted for the Dutch Safety Board Into the Accident of TK1951, Boeing 737-800 Near Amsterdam Schiphol Airport" (PDF). Lunds Universitet School of Aviation. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ a b Hamby, Chris; Moses, Claire (6 February 2020). "Boeing Refuses to Cooperate With New Inquiry Into Deadly Crash". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Who's in Control?". Mayday. Season 11. 2010. Discovery Channel Canada / National Geographic Channel.

External links

[edit]| External images | |

|---|---|

- Dutch Safety Board

- Final Accident Report (Archive) (Alternate URL)

- Final Accident Report (in Dutch) (Archive) – The Dutch report is the version of record; if there are differences between the English and Dutch versions, the Dutch prevails

- Index of publications: English | Dutch

- Turkish Airlines

- Turkish Airlines Special Issues at the Wayback Machine (archive index) (official announcements)

- Passenger List at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

- Skybrary: Human Factors / Loss of Control

- Google Earth flight path

- Google Maps flight path (openATC)

- Flight tracker

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- The record of last radio call between ATC and the crew. (site in Turkish)

- Radartrack crashed airplane

- Associated Press: Airliner Crashes in Amsterdam on YouTube (video)

- BBC World News: Nine killed in Amsterdam plane crash on YouTube (video)

- "Nine dead, 84 injured in Turkish Airlines plane crash in Amsterdam". Hurriyet Daily News Online. 25 February 2009.

- Aviation accidents and incidents in 2009

- Aviation accidents and incidents in the Netherlands

- Aviation accidents and incidents involving flight instrument failure

- Accidents and incidents involving the Boeing 737 Next Generation

- Airliner accidents and incidents caused by pilot error

- Turkish Airlines accidents and incidents

- 2009 disasters in the Netherlands

- History of North Holland

- February 2009 events in Europe

- Netherlands–Turkey relations

- Airliner accidents and incidents caused by stalls