Synthetic drug

Synthetic drugs refer to substances that are artificially modified from naturally-occurring drugs and are capable of exhibiting both therapeutic and psychoactive effects.

In the medical setting, synthetic drugs possess psychotropic effects which can cure insomnia. Since there are limited clinical trials and human studies, the pharmacology and drug effects of most of the synthetic drugs are not well-known. Misuse of synthetic drugs can be fatal so take advice from the professionals before use.

Substances that possess the latter effect are known as New Psychoactive Substances (NPS). Their purpose is to mimic the actions of illicit substances by altering the structure of the original drug. By doing so, the “synthesized drug” can appear in the market without being easily detected. However, the uncertainty in the toxic effects of these substances puts the public's health at risk.[1] At present, these drugs are monitored by the Early Warning System (EWS).The major categories of NPS include synthetic stimulants, synthetic cannabinoids and synthetic depressants. Common examples from these categories are phenethylamines, cannabinoids and benzodiazepines. To exert the psychoactive effect, specific receptors such as cannabinoid, dopamine and serotonin receptors are either stimulated or inhibited[2]

Common synthetic drugs

[edit]Synthetic cannabinoids

[edit]

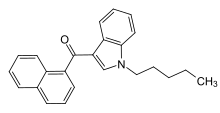

There are seven major structural groups, which are naphthoylindoles, naphthylmethylindoles, naphthoypyrroles, naphthylmethylindenes, phenylacetylindoles, cyclohexylphenols and classical cannabinoids respectively.[3] Compared with classical cannabinoids, synthetic cannabinoids differ structurally. Some common synthetic cannabinoids are available in the market such as JWH-018, which is the most well-known naphthoylindole and JWH-250, a phenylacetylindole. They are sold under the brand name ”Spice” as a recreational drug over the past decade.[4]

Phenethylamines

[edit]Phenethylamines can be classified into ring-substituted and non-ring-substituted form. Ring-substituted Phenethylamines include ‘D-series’ and ‘2C-series’ while common non-ring-substituted Phenethylamines contain Benzodifurans, PMMA, etc.[5]

Novel benzodiazepines(Xanax)

[edit]Alprazolam is a generic medication derived from benzodiazepines with the brand name Xanax.

Medical uses

[edit]Synthetic cannabinoids can provide psychotropic effects such as relieving nausea and dizziness. Phenethylamine can relieve depressive symptoms while Alprazolam can treat insomnia, panic attack and anxiety.[6] The most common delivery routes of Alprazolam and Phenethylamine are by oral administration. Both of which are available in the dosage forms of pills and tablets. Synthetic cannabinoids are naturally in solid and oil form and are delivered by smoking.[3]

Adverse effects

[edit]The adverse effects of synthetic drugs are hard to determine as they usually contain other chemicals with variable concentrations and human studies are limited.

Synthetic cannabinoids can cause cardiovascular problems such as tachyarrhythmia, seizures, psychological disorders and potential carcinogenic effects. Addiction and withdrawal symptoms which are linked to chronic use of synthetic cannabinoid include cognitive disturbances (e.g. difficulties in thinking), ‘profuse sweating’, central nervous system and gastrointestinal disturbances (e.g. nausea and vomiting).[7][8]

The adverse effect of Phenethylamines depends on the type of the drug. ‘D series’ cause more long-lasting effects than other phenylethylamines such as tachycardia. At high doses, ‘2C series’ produce hallucinogenic and entactogenic effects.[9]

Alprazolam can cause central nervous system disturbances and thoughts of suicide.[6]

Contraindications/Precautions

[edit]Synthetic cannabinoids are best avoided in users who suffer from rapid heart rate, vomiting, agitation, confusion and hallucination.

Pregnant women are also not recommended to take phenethylamines as the effects on fetus are not known. In addition, use of phenethylamine might cause people with bipolar disorder to convert from depression to mania and worsened schizophrenia symptoms. As the drug also affects the central nervous system, administration of such drug before surgery is not recommended.

Benzodiazepines can cross the placenta and can be excreted in breast milk therefore Alprazolam is contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation. Alprazolam is a CYP3As substrate so we should avoid CYP3As inhibitors such as cimetidine which is a CYP3A4 inhibitor.

Pharmacology: Pharmacodynamics/Mechanism of Action(MOA)

[edit]Synthetic cannabinoids act as Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists (SCRA)[10] by binding to cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 . Its binding towards CB1 receptor will lead to receptor phosphorylation that recruits β-arrestin 1 and β-arrestin 2, resulting in a loss of responsiveness and internalization (endocytosis of molecules by the cell). Stimulation of CB1 receptor causes the dissociation of the βγ subunits of pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins (Gi /Go) from the α subunit (Giα) which then contributes to acute inhibition of synaptic neurotransmitter release. β-arrestin can also stimulate the mitogen-activated protein kinase, thus inducing additional cellular effects. Synthetic cannabinoids can also bind to receptors other than CB1 and CB2 to activate inotropic transient receptor potential channels for cell membrane depolarization and Ca2+ influx.[11]

Phenethylamines, which can act as either stimulants or hallucinogens, are indirectly acting sympathomimetic amines. Stimulants can modulate the levels and action of monoamine neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin and noradrenaline for vasoconstriction and elevation in blood pressure. For example, 10-100 μM amphetamine can reach the vasoconstriction effect. Hallucinogen (psychedelics) can mediate specific serotonin-receptor activities and produce hallucinations. They may have residue stimulant activity as well. In some animal studies, Phenethylamines have negative inotropism in isolated cardiac tissues of rats due to stimulation of TAAR1, which is in contrast with human pharmacology.[12]

Alprazolam binds to GABA type-A benzodiazepine receptor sites which are the members of the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel (PLGIC) superfamily. It mediates phasic inhibition and extrasynaptically to mediate tonic inhibition. Once attached, conformational changes occur which stabilize the receptors and inhibitory signals are produced[13]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Synthetic cannabinoids are delivered by smoking. In a human study, after 50 μg/kg smoked JWH-018 are delivered, one male and a female have their serum concentration of 8.1 and 10.2 μg/L respectively after 5 minutes, down to 4.6 and 6.1 μg/L after 15 minutes, suggesting the biological half-life of JWH-018 is short. 13 phase 1 metabolites are identified. Monohydroxylated and dihydrodiol metabolites are most prevalent metabolites of synthetic cannabinoids. UGT1A1, UGT1A3, UGT1A9, UGT1A10 and UGT2B7 isoenzymes were primarily responsible for JWH-018 and JWH-073 metabolites’ conjugation and had high affinity for hydroxylated metabolites (Km=12–18 mmol/L). Generation of JWH-018-N-4- and 5-hydroxypentyl (JWH-018 metabolites) was primarily mediated by CYP2C9 followed by CYP1A2 and CYP2C19. CYP3A4 catalyzed JWH-018-N-4-hydroxypentyl production but with lower activity than CYP1A2 and CP2C19. The drugs are mainly excreted as urine.[11]

Phenethylamines are first-order kinetics with half life of 5 to 10 minutes which are absorbed by ingestion. The drugs have low concentration in the brain due to low biological half-life. It is difficult to measure the plasma concentration due to low stability of Phenethylamine. There are two possible metabolism pathways. The first possible pathway is metabolism by MAO-B (an intracellular enzyme mainly in the brain and tightly bound to the outer membrane of mitochondria which deaminates free primary and secondary amines) to form phenylacetic acid due to MAO-B selectivity on non-polar aromatic amines. Then, the metabolites undergo N-methylation by non-specific N-methyltransferase(NMT) or by phenylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase (PNMT) (found in the adrenal medulla) to form secondary amines and sympathetic neurotransmitter noradrenaline. The second possible pathway is deamination of the drug by the semi-carbazide-sensitive amine oxidases (SSAO) (found in the vascular tissue and have similar metabolism to MAO). An alpha-methyl side chain renders the drug immune to deamination in the gut. The drugs are mainly excreted in feces and urine.[14]

Alprazolam has high oral bioavailability (84-91%) in which its maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) is reached after 1 to 2 hours. When taken with food, Cmax is increased by 25%. The half-life profile of this drug for different populations is illustrated in the following table:

| Population | Half-life (hrs) |

|---|---|

| Healthy individuals | 11.2 |

| Obese | 10.7-15.8 |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 19.7 |

In terms of race, the half-life is 25% higher in Asian patients compared to Caucasians. For the extended-release formulation, it has a half-life of 10.7-15.8 hours in healthy adult patients. Alprazolam has a volume of distribution following oral administration of 0.8-1.3L/kg. Its protein binding in plasma is 80% (mainly albumin bound) and capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier. It is metabolized to less effective metabolites by various CYP450 enzymes including CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP3A7, and CYP2C9. The majority of alprazolam metabolism is mediated by hydroxylation via CYP3As. 4-hydroxyalprazolam has 20% the binding affinity of the parent drug, alpha-hydroxyalprazolam has 66% the affinity, and the benzophenone metabolite has <1% the affinity. The drugs are mainly excreted in urine as unchanged Alprazolam. <10% of the dose is eliminated as alpha-hydroxy-alprazolam and 4-hydroxy-alprazolam.[13]

Chemistry

[edit]Detection in body fluids

[edit]Drug detection in body fluids requires specific reference data from the target drug. A common pitfall in the detection of New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) is the lack of reference data available for spectrometers to identify the presence of structurally modified illicit substances. Another drug detection technique, immunoassay, relies on active antibodies to detect the target drug by selectivity. If the drug is structurally modified, the original antibodies will respond in a different fashion which will give false positive or negative results.[15]

Structure-activity relationship

[edit]Synthetic cannabinoids

[edit]Synthetic cannabinoids, members of the aminoalkylindole class, made its first appearance in 2008. It was given the name 'JWH’ because a chemist called John W. Huffman synthesized them in the 1960s. Most synthetic analogs of cannabinoids mimic the structure of 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which makes them an agonist to the CB1(Type I) and CB2 (Type II) cannabinoid receptors. CB1 in particular, is expressed in the central nervous system and largely responsible for the psychoactive effect..[16]

A typical agonist consists of the following components: head, linker core and tail. Altering the structure from each component will affect the drug's affinity to the cannabinoid receptors. For instance, when a fluoride or nitrile group is attached to the carbon chains, the affinity for CB1 will increase. The aromatic rings from the aminoalkylindole class also play the role of enhancing the affinity by forming a hydrophobic cavity to stabilize the CB1 receptors.[17] As legislation becomes tightened under the monitoring of Early Warning System (EWS), attempts are made to alter the structure which produce new analogues such as the Cyclopropylindoles (UR-144) and adamantylindoles (APINACA).[18]

Novel benzodiazepines

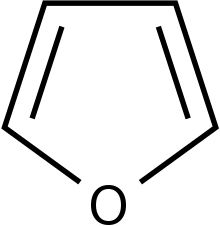

[edit]Analogues of novel benzodiazepines are able to possess antibacterial activities. When they are tested against various bacterial strains, the isoxazolyl analogues with the p-chlorophenyl group (p-CIC6H4) attached have shown to be the most effective agent against the majority of the strains. Furthermore, attachment of an electron withdrawing groups and heterocyclic rings such as thiophene and furan will increase the inhibitory effect against bacteria. Novel benzodiazepines can also modulate the Central Nervous System by docking to the human dopamine transporter D3. Enantiomers of imidazole [1,4] diazepines with either a methyl group (CH3) or a propyl group attached enhance the binding affinity towards human dopamine D3 receptors.[19]

Phenylethylamine

[edit]In general, phenylethylamine consists of an aromatic ring connected to an amine group which is 2 carbons away.[20] Each type of phenylethylamine differs by the substitutions at the alpha and beta carbon position. When a methyl group is attached at the alpha position, the compound becomes amphetamines which has the ability to modulate the 5HT-2A serotonin receptors. Eventually, the activated receptors cause hallucinations.[21] To ensure sufficient binding, the agonists must contain a primary amine, methoxy group and hydrophobic functional groups.[22]

Legality and Regulation

[edit]The Early Warning System (EWS), operated by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug addiction (EMCDDA), overseas illicit substances that appear in the market. Established in 1997, It formed part of the framework that allows the European Union to rapidly detect NPS that pose a risk to the public's health. Due to the tightening of legislation, most NPS are now illegal in the UK and Germany. Upon the emergence of NPS, this agency responds in the following manner:

| Steps | Procedure |

|---|---|

| 1 | Formal notification |

| 2 | Monitoring and response |

| 3 | Initial report writing |

When the EWS detects a new drug, the substance will be reported to EMCDDA along with any analytical data such as structures, analysts or components found pertaining to that particular drug. Then, an interconnected system is established to closely monitor the development of the substance. If harm is induced, an initial report is drafted to document the adverse effects of the drug.

Trends

[edit]In recent years, a new type of benzodiazepine known as ‘Designer benzodiazepines’ are becoming available in Europe. It is based on the premise of modifying the structure of illicit drugs to evade international control measures. By early 2021, EMCDDA has monitored 30 designer benzodiazepines through the EWS. However, not much information is available regarding the market size of new benzodiazepines. Seizures reports from police and customs authorities have shown that new benzodiazepine is not of great interest compared to other NPS groups. In 2019, 4% of police seizures is attributed to benzodiazepines.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Rinaldi, Raffaella; Bersani, Giuseppe; Marinelli, Enrico; Zaami, Simona (2020-03-07). "The rise of new psychoactive substances and psychiatric implications: A wide‐ranging, multifaceted challenge that needs far‐reaching common legislative strategies". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 35 (3): e2727. doi:10.1002/hup.2727. ISSN 0885-6222. PMID 32144953. S2CID 212621941.

- ^ Shafi, Abu; Berry, Alex J.; Sumnall, Harry; Wood, David M.; Tracy, Derek K. (2020-09-26). "New psychoactive substances: a review and updates". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 10: 204512532096719. doi:10.1177/2045125320967197. ISSN 2045-1253. PMC 7750892. PMID 33414905.

- ^ a b "Synthetic cannabinoids and 'Spice' drug profile | www.emcdda.europa.eu". www.emcdda.europa.eu. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ Banister, Samuel D.; Stuart, Jordyn; Kevin, Richard C.; Edington, Amelia; Longworth, Mitchell; Wilkinson, Shane M.; Beinat, Corinne; Buchanan, Alexandra S.; Hibbs, David E.; Glass, Michelle; Connor, Mark (2015-05-08). "Effects of Bioisosteric Fluorine in Synthetic Cannabinoid Designer Drugs JWH-018, AM-2201, UR-144, XLR-11, PB-22, 5F-PB-22, APICA, and STS-135". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 6 (8): 1445–1458. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00107. ISSN 1948-7193. PMID 25921407.

- ^ "Details for Phenethylamines". www.unodc.org. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ a b "Alprazolam: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- ^ "Synthetic cannabinoids: What are they? What are their effects? | HSB | NCEH". www.cdc.gov. 2022-04-11. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- ^ Cooper, Ziva D. (2016-06-28). "Adverse Effects of Synthetic Cannabinoids: Management of Acute Toxicity and Withdrawal". Current Psychiatry Reports. 18 (5): 52. doi:10.1007/s11920-016-0694-1. ISSN 1523-3812. PMC 4923337. PMID 27074934.

- ^ "Details for Phenethylamines". www.unodc.org. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- ^ "Details for Synthetic cannabinoids". www.unodc.org. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- ^ a b Walsh, Kenneth B.; Andersen, Haley K. (2020-08-25). "Molecular Pharmacology of Synthetic Cannabinoids: Delineating CB1 Receptor-Mediated Cell Signaling". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (17): 6115. doi:10.3390/ijms21176115. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 7503917. PMID 32854313.

- ^ Broadley, Kenneth J. (2009-12-04). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. ISSN 1879-016X. PMID 19948186.

- ^ a b "Xanax: Uses, Dosage, Side Effects & Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- ^ Janssen, Paul A. J.; Leysen, Josée E.; Megens, Anton A. H. P.; Awouters, Frans H. L. (1999-09-01). "Does phenylethylamine act as an endogenous amphetamine in some patients?". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2 (3): 229–240. doi:10.1017/s1461145799001522. ISSN 1461-1457. PMID 11281991.

- ^ Favretto, Donata; Pascali, Jennifer P.; Tagliaro, Franco (2013-04-23). "New challenges and innovation in forensic toxicology: Focus on the "New Psychoactive Substances"". Journal of Chromatography A. 1287: 84–95. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2012.12.049. ISSN 0021-9673. PMID 23332303.

- ^ Pintori, Nicholas; Loi, Barbara; Mereu, Maddalena (2017-05-14). "Synthetic cannabinoids: the hidden side of Spice drugs". Behavioural Pharmacology. 28 (6): 409–419. doi:10.1097/fbp.0000000000000323. ISSN 0955-8810. PMID 28692429. S2CID 4913772.

- ^ Patel, Monica; Finlay, David B.; Glass, Michelle (2021-11-26). "Biased agonism at the cannabinoid receptors – Evidence from synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists". Cellular Signalling. 78: 109865. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109865. ISSN 0898-6568. PMID 33259937. S2CID 227254963.

- ^ CE, Smith, JP Sutcliffe, OB Banks (2015-06-02). An overview of recent developments in the analytical detection of new psychoactive substances (NPSs). Royal Society of ChemistryLondon. OCLC 1269494147.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arora, Nidhi; Dhiman, Prashant; Kumar, Shubham; Singh, Gurpreet; Monga, Vikramdeep (2020-02-17). "Recent advances in synthesis and medicinal chemistry of benzodiazepines". Bioorganic Chemistry. 97: 103668. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103668. ISSN 0045-2068. PMID 32106040. S2CID 211556193.

- ^ Khan, JaVed I.; Kennedy, Thomas J.; Christian, Donnell R. (2012), "Phenethylamines", Basic Principles of Forensic Chemistry, Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, pp. 157–176, doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-437-7_13, ISBN 978-1-934115-06-0, retrieved 2022-03-16

- ^ Valento, Matthew; Lebin, Jacob (2017-07-06). "Emerging Drugs of Abuse: Synthetic Cannabinoids, Phenylethylamines (2C Drugs), and Synthetic Cathinones". Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 18 (3): 203–211. doi:10.1016/j.cpem.2017.07.009. ISSN 1522-8401.

- ^ E, Isberg, Vignir Paine, James Leth-Petersen, Sebastian Kristensen, Jesper Langgaard Gloriam, David (2013). Structure-activity relationships of constrained phenylethylamine ligands for the serotonin 5-ht2 receptors. OCLC 1035205954.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evans-Brown, Michael; Sedefov, Roumen (2018), "Responding to New Psychoactive Substances in the European Union: Early Warning, Risk Assessment, and Control Measures", New Psychoactive Substances, vol. 252, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 3–49, doi:10.1007/164_2018_160, ISBN 978-3-030-10560-0, PMID 30194542, retrieved 2022-03-16

- ^ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2021). New benzodiazepines in Europe: a review. LU: Publications Office. doi:10.2810/725973. ISBN 9789294976413.