Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory

Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory | |

| Names | Explorer-84 MIDEX-3 Swift Gamma Ray Burst Explorer |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Gamma-ray astronomy |

| Operator | NASA / Pennsylvania State University |

| COSPAR ID | 2004-047A |

| SATCAT no. | 28485 |

| Website | swift |

| Mission duration | 2 years (planned)[1] 20 years, 28 days (in progress) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Explorer LXXXIV |

| Spacecraft type | Swift Gamma Ray Burst Explorer |

| Bus | LEOStar-3 |

| Manufacturer | Spectrum Astro |

| Launch mass | 1,470 kg (3,240 lb) |

| Dry mass | 613 kg (1,351 lb) |

| Payload mass | 843 kg (1,858 lb) |

| Dimensions | 5.6 × 5.4 m (18 × 18 ft)[2] |

| Power | 1040 watts |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 20 November 2004, 17:16:01 UTC |

| Rocket | Delta II 7320-10C (Delta 309) |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral, SLC-17A |

| Contractor | Boeing Defense, Space & Security[3] |

| Entered service | 1 February 2005 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric orbit[4] |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Perigee altitude | 585 km (364 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 604 km (375 mi) |

| Inclination | 20.60° |

| Period | 96.60 minutes |

| Instruments | |

| Burst Alert Telescope (BAT) UltraViolet Optical Telescope (UVOT) X-Ray Telescope (XRT) | |

Swift Gamma Ray Burst Explorer Explorer program | |

Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, previously called the Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Explorer, is a NASA three-telescope space observatory for studying gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) and monitoring the afterglow in X-ray, and UV/visible light at the location of a burst.[5] It was launched on 20 November 2004, aboard a Delta II launch vehicle.[4] Headed by principal investigator Neil Gehrels until his death in February 2017, the mission was developed in a joint partnership between Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) and an international consortium from the United States, United Kingdom, and Italy. The mission is operated by Pennsylvania State University as part of NASA's Medium Explorer program (MIDEX).

The burst detection rate is 100 per year, with a sensitivity ~3 times fainter than the BATSE detector aboard the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory. The Swift mission was launched with a nominal on-orbit lifetime of two years. Swift is a NASA MIDEX (medium-class Explorer) mission. It was the third to be launched, following IMAGE and WMAP.[5]

While originally designed for the study of gamma-ray bursts, Swift now functions as a general-purpose multi-wavelength observatory, particularly for the rapid followup and characterization of astrophysical transients of all types. As of 2020, Swift received 5.5 Target of Opportunity observing proposals per day, and observes ~70 targets per day, on average.[6]

Overview

[edit]Swift is a multi-wavelength space observatory dedicated to the study of gamma-ray bursts. Its three instruments work together to observe GRBs and their afterglows in the gamma-ray, X-ray, ultraviolet, and optical wavebands.

Based on continuous scans of the area of the sky with one of the instrument's monitors, Swift uses momentum wheels to autonomously slew into the direction of possible GRBs. The name "Swift" is not a mission-related acronym, but rather a reference to the instrument's rapid slew capability, and the nimble swift (bird of the same name).[7] All of Swift's discoveries are transmitted to the ground and those data are available to other observatories which join Swift in observing the GRBs.

In the time between GRB events, Swift is available for other scientific investigations, and scientists from universities and other organizations can submit proposals for observations.

The Swift Mission Operation Center (MOC), where commanding of the satellite is performed, is located in State College, Pennsylvania and operated by the Pennsylvania State University and industry subcontractors. The Swift main ground station is located at the Broglio Space Center near Malindi on the coast of eastern Kenya, and is operated by the Italian Space Agency (ASI). The Swift Science Data Center (SDC) and archive are located at the Goddard Space Flight Center outside Washington, D.C. The United Kingdom Swift Science Data Centre is located at the University of Leicester.

The Swift satellite bus was built by Spectrum Astro, which was later acquired by General Dynamics Advanced Information Systems,[8] which was in turn acquired by Orbital Sciences Corporation (now Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems).

Instruments

[edit]Burst Alert Telescope (BAT)

[edit]

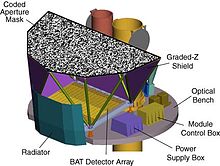

The BAT detects GRB events and computes its coordinates in the sky. It covers a large fraction of the sky (over one steradian fully coded, three steradians partially coded; by comparison, the full sky solid angle is 4π or about 12.6 steradians). It locates the position of each event with an accuracy of 1 to 4 arcminutes within 15 seconds. This crude position is immediately relayed to the ground, and some wide-field, rapid-slew ground-based telescopes can catch the GRB with this information. The BAT uses a coded-aperture mask of 52,000 randomly placed 5 mm (0.20 in) lead tiles, 1 m (3 ft 3 in) above a detector plane of 32,768 4 mm (0.16 in) Cadmium zinc telluride (CdZnTe) hard X-ray detector tiles; it is purpose-built for Swift. Energy range: 15–150 keV.[9]

X-ray Telescope (XRT)

[edit]

The XRT [10] can take images and perform spectral analysis of the GRB afterglow. This provides more precise location of the GRB, with a typical error circle of approximately 2 arcseconds radius. The XRT is also used to perform long-term monitoring of GRB afterglow light-curves for days to weeks after the event, depending on the brightness of the afterglow. The XRT uses a Wolter Type I X-ray telescope with 12 nested mirrors, focused onto a single MOS charge-coupled device (CCD) similar to those used by the XMM-Newton EPIC MOS cameras. On-board software allows fully automated observations, with the instrument selecting an appropriate observing mode for each object, based on its measured count rate. The telescope has an energy range of 0.2–10 keV.[11]

Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope (UVOT)

[edit]

After Swift has slewed towards a GRB, the UVOT is used to detect an optical afterglow. The UVOT provides a sub-arcsecond position and provides optical and ultra-violet photometry through lenticular filters and low resolution spectra (170–650 nm) through the use of its optical and UV grisms. The UVOT is also used to provide long-term follow-ups of GRB afterglow lightcurves. The UVOT is based on the XMM-Newton's Optical Monitor (OM) instrument, with improved optics and upgraded onboard processing computers.[12]

On 9 November 2011, UVOT photographed the asteroid 2005 YU55 as the asteroid made a close flyby of the Earth.[13]

On 3 June 2013, UVOT unveiled a massive ultraviolet survey of the nearby Magellanic Clouds.[14]

In August 2017, UVOT imaged UV emissions from gravitational wave event GW170817 detected by LIGO & Virgo detectors.[15][16]

Experiments

[edit]

Burst Alert Telescope (BAT)

[edit]BAT (Burst Alert Telescope) is a gamma ray telescope, built by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, uses a coded aperture to locate the source. The software to locate the source is provided by the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). The CdZnTe detector of 5,200 cm2 (810 sq in) area, consisting of 32,500 units of 4 × 4 × 2 mm (0.157 × 0.157 × 0.079 in), can pin-point the location of sources within 1.4 arcminutes. The energy range is 15-150 keV.[17]

Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope (UVOT)

[edit]UVOT (Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope) monitors the afterglow in ultraviolet and visible light, and locates the source at an accuracy of one arcsecond. Its aperture is 30 cm (12 in), with an f-number equal to 12.7, and is backed by 2048 x 2048 photon counting CCD pixels. The source location accuracy is better than one arcsecond.[18]

X-Ray Telescope (XRT)

[edit]XRT (X-Ray Telescope) aims at the source more accurately, and monitors the afterglow in X-rays. It was built jointly by the Pennsylvania State University (PSU), the Brera Astronomical Observatory, Italy, and the University of Leicester, United Kingdom. It has a detector of area 135 cm2 (20.9 sq in) consisting of 600 x 600 pixels, and covers the energy range of 0.2-10 keV. It can locate the afterglow source at an accuracy of four arcseconds.[19]

Mission goals

[edit]The Swift mission has four key scientific objectives:

- To determine the origin of GRBs. There seem to be at least two types of GRBs, only one of which can be explained with a hypernova, creating a gamma-ray beam. More data is needed to explore other explanations

- To use GRBs to expand understanding of the young universe. GRBs seem to take place at "cosmological distances" of many millions or billions of light-years, which means they can be used to probe the distant, and therefore young, cosmos

- To conduct an all-sky survey which will be more sensitive than any previous one, and will add significantly to scientific knowledge of astronomical X-ray sources. Thus, it could also yield unexpected results

- To serve as a general purpose gamma-ray/X-ray/optical observatory platform, performing rapid "target of opportunity" observations of many transient astrophysical phenomena, such as supernova

Mission history

[edit]

Swift was launched on 20 November 2004, at 17:16:01 UTC aboard a Delta II 7320-10C from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and reached a near-perfect orbit of 585 × 604 km (364 × 375 mi) altitude, with an inclination of 20.60°.[4]

On 4 December 2004, an anomaly occurred during instrument activation when the Thermo-Electric Cooler (TEC) Power Supply for the X-Ray Telescope did not turn on as expected. The XRT Team at University of Leicester and Pennsylvania State University were able to determine on 8 December 2004 that the XRT would be usable even without the TEC being operational. Additional testing on 16 December 2004 did not yield any further information as to the cause of the anomaly.

On 17 December 2004 at 07:28:30 UTC, the Swift Burst Alert Telescope (BAT) triggered and located on board an apparent gamma-ray burst during launch and early operations.[20] The spacecraft did not autonomously slew to the burst since normal operation had not yet begun, and autonomous slewing was not yet enabled. Swift had its first GRB trigger during a period when the autonomous slewing was enabled on 17 January 2005, at about 12:55 UTC. It pointed the XRT telescope to the on-board computed coordinates and observed a bright X-ray source in the field of view.[21]

On 1 February 2005, the mission team released the first light picture of the UVOT instrument and declared Swift operational.

By May 2010, Swift had detected more than 500 GRBs.[22]

By October 2013, Swift had detected more than 800 GRBs.[23]

On 27 October 2015, Swift detected its 1,000th GRB, an event named GRB 151027B and located in the constellation Eridanus.[24]

On 10 January 2018, NASA announced that the Swift spacecraft had been renamed the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory in honor of mission PI Neil Gehrels, who died in early 2017.[25][26]

Swift entered safe mode on March 15, 2024 (after the 2nd of 4 gyroscopes failed) and was not conducting science. A software patch for two-gyroscope mode was developed, uplinked and tested in April 2024, and Swift returned to nominal operations at that point.[27]

Notable detections

[edit]

- 9 May 2005: Swift detected GRB 050509B, a burst of gamma rays that lasted one-twentieth of a second. The detection marked the first time that the accurate location of a short-duration gamma-ray burst had been identified and the first detection of X-ray afterglow in an individual short burst.[28][29]

- 4 September 2005: Swift detected GRB 050904 with a redshift value of 6.29 and a duration of 200 seconds (most of the detected bursts last about 10 seconds). It was also found to be the most distant yet detected, at approximately 12.6 billion light-years.

- 18 February 2006: Swift detected GRB 060218, an unusually long (about 2000 seconds) and nearby (about 440 million light-years) burst, which was unusually dim despite its close distance, and may be an indication of an imminent supernova.

- 14 June 2006: Swift detected GRB 060614, a burst of gamma rays that lasted 102 seconds in a distant galaxy (about 1.6 billion light-years). No supernova was seen following this event (and GRB 060505 to deep limits) leading some to speculate that it represented a new class of progenitors. Others suggested that these events could have been massive star deaths, but ones which produced too little radioactive 56Ni to power a supernova explosion.

- 9 January 2008: Swift was observing a supernova in NGC 2770 when it witnessed an X-ray burst coming from the same galaxy. The source of this burst was found to be the beginning of another supernova, later called SN 2008D. Never before had a supernova been seen at such an early stage in its evolution. Following this stroke of luck (position, time, most appropriate instruments), astronomers were able to study in detail this Type Ibc supernova with the Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Very Large Array in New Mexico, the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii, Gemini South in Chile, the Keck I telescope in Hawaii, the 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) PAIRITEL telescope at Mount Hopkins, the 200-inch and 60 in (1,500 mm) telescopes at the Palomar Observatory in California, and the 3.5 m (11 ft) telescope at the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico. The significance of this supernova was likened by discovery team leader Alicia Soderberg to that of the Rosetta Stone for egyptology.[30]

- 8 and 13 February 2008: Swift provided critical information about the nature of Hanny's Voorwerp, mainly the absence of an ionizing source within the Voorwerp or in the neighboring IC 2497.

- 19 March 2008: Swift detected GRB 080319B, a burst of gamma rays amongst the brightest celestial objects ever witnessed. At 7.5 billion light-years, Swift established a new record for the farthest object (briefly) visible to the naked eye. It was also said to be 2.5 million times intrinsically brighter than the previous brightest accepted supernova (SN 2005ap). Swift observed a record four GRBs that day, which also coincided with the death of noted science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke.[31]

- 13 September 2008: Swift detected GRB 080913, at the time the most distant GRB observed (12.8 billion light-years) until the observation of GRB 090423 a few months later.[32][33]

- 23 April 2009: Swift detected GRB 090423, the most distant cosmic explosion ever seen at that time, at 13.035 billion light-years. In other words, the universe was only 630 million years old when this burst occurred.[34]

- 29 April 2009: Swift detected GRB 090429B, which was found by later analysis published in 2011 to be 13.14 billion light-years distant (approximately equivalent to 520 million years after the Big Bang), even farther than GRB 090423.[35]

- 16 March 2010: Swift tied its record by again detecting and localizing four bursts in a single day.

- 13 April 2010: Swift detected its 500th GRB.[36]

- 28 March 2011: Swift detected Swift J1644+57 which subsequent analysis showed to possibly be the signature of a star being disrupted by a black hole or the ignition of an active galactic nucleus.[37] "This is truly different from any explosive event we have seen before", said Joshua Bloom of the University of California, Berkeley, the lead author of the study published in the June issue of Science.[38]

- 16 and 17 September 2012: BAT triggered two times on a previously unknown hard X-ray source, named Sw J1745-26, a few degrees from the Galactic Center. The outburst, produced by a rare X-ray nova, announced the presence of a previously unknown stellar-mass black hole undergoing a dramatic transition from the low/hard to the high/soft state.[39][40][41]

- 2013: Discovery of ultra-long class of gamma-ray bursts

- 24 April 2013: Swift detected an X-ray flare from the Galactic Center. This proved not to be related to Sgr A* but to a previously unsuspected magnetar. Later observations by the NuSTAR and the Chandra X-ray Observatory confirmed the detection.[42]

- 27 April 2013: Swift detected the "shockingly bright" Gamma-ray burst GRB 130427A. Observed simultaneously by the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, it is one of the five closest GRBs detected and one of the brightest seen by either space telescope.[43]

- 3 June 2013: Evidence for kilonova emission in short GRB

- 23 April 2014: Swift detected the strongest, hottest, and longest-lasting sequence of stellar flares ever seen from a nearby red dwarf star. The initial blast from this record-setting series of explosions was as much as 10,000 times more powerful than the largest solar flare ever recorded.[44]

- 3 May 2014: Detection of a UV Pulse from an iPTF discovered young Type Ia SN

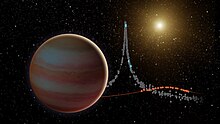

- June–July 2015: The brown dwarf OGLE-2015-BLG-1319 was discovered using the gravitational microlensing detection method in a joint effort between Swift, Spitzer Space Telescope, and the ground-based Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment, the first time two space telescopes have observed the same microlensing event. This method was possible because of the large separation between the two spacecraft: Swift is in low Earth orbit while Spitzer is more than one AU distant in an Earth-trailing heliocentric orbit. This separation provided significantly different perspectives of the brown dwarf, allowing for constraints to be placed on some of the object's physical characteristics.[45]

- 27 October 2015: Swift detected its 1000th gamma-ray burst, GRB 151027B.[24]

- 18 August 2017: Swift discovers UV emission from the kilonova AT 2017gfo, the electromagnetic counterpart to GW170817.[16]

- 23 September 2017: Swift is the first to identify TXS 0506+056 as the possible source of the IceCube-170922A extremely high energy (EHE) neutrinos.[46]

- 14 January 2019: Swift discovers the most powerful observed gamma-ray burst, GRB 190114C, reaching teraelectronvolt energies.[47]

- 09 October 2022: Swift discovers, simultaneously with Fermi, GRB 221009A, one of the closest GRBs ever detected and the brightest ever detected.

See also

[edit]- List of gamma-ray bursts

- List of X-ray space telescopes

- GRB 221009A

- Space Variable Objects Monitor (SVOM), the planned successor of Swift

References

[edit]- ^ "NASA Swift Mission Extended for 4 More Years". Omitron. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ^ "Swift Facts and FAQ". Sonoma State University. 28 March 2008. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Swift Explorer" (PDF). NASA. 1 November 2004. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c "Trajectory: Swift (Explorer 84) 2004-047A". NASA. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Display: SWIFT (Explorer 84) 2004-047A". NASA. 28 October 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Swift Mission Operations Center". PSU. 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Swift Guest Investigator Program Frequently Asked Questions". NASA. 26 September 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Taylor, Ed (6 October 2011). "Launch of a satellite made by the General Dynamics C4 Systems delayed". East Valley Tribune. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Swift's Burst Alert Telescope (BAT)". NASA. 28 February 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Burrows, David N.; et al. (October 2005). "The Swift X-Ray Telescope". Space Science Reviews. 120 (3–4): 165–195. arXiv:astro-ph/0508071. Bibcode:2005SSRv..120..165B. doi:10.1007/s11214-005-5097-2. S2CID 54003617.

- ^ "Swift's X-Ray Telescope (XRT)". NASA. 15 August 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Swift's Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope (UVOT)". NASA. 14 December 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Swift Captures Flyby of Asteroid 2005 YU55". NASA. 11 November 201. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA's Swift Produces Best Ultraviolet Maps of the Nearest Galaxies". NASA. 3 June 2013.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ NASA Missions Catch First Light from a Gravitational-Wave Event 2017

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Evans, P. A. (16 October 2017). "Swift and NuSTAR observations of GW170817: detection of a blue kilonova". Science. 358 (6370): 1565–1570. arXiv:1710.05437. Bibcode:2017Sci...358.1565E. doi:10.1126/science.aap9580. PMID 29038371. S2CID 4028270.

- ^ "Experiment: Burst Alert Telescope (BAT)". NASA. 28 October 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Experiment: Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope (UVOT)". NASA. 28 October 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Experiment: X-Ray Telescope (XRT)". NASA. 28 October 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "GRB041217: The First GRB Located On-Board Swift". NASA. 17 December 2004. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "GRB050117: Swift XRT Position". NASA. 17 January 2005. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA's Swift Catches 500th Gamma-ray Burst". NASA. 19 April 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Swift GRB Table Stats". NASA. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "NASA's Swift Spots its Thousandth Gamma-ray Burst". NASA. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (11 January 2018). "NASA renames Swift mission after astronomer Neil Gehrels". SpaceNews. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Cofield, Calla (10 January 2018). "NASA Renames Swift Observatory in Honor of Late Principal Investigator". Space.com. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ "The Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory". swift.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Whitehouse, David (11 May 2005). "Blast hints at black hole birth". BBC News. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Bloom, Joshua (31 May 2005). "Astronomers hot on the trail of nature's exotic flashers" (Press release). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "NASA's Swift Satellite Catches a Star Going "Kaboom!"" (Press release). NASA. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA Satellite Detects Naked-Eye Explosion Halfway Across Universe". NASA. 20 March 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (28 October 2009). "More Observations of GRB 090423, the Most Distant Known Object in the Universe". Universe Today. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ^ Garner, Robert (19 September 2008). "NASA's Swift Catches Farthest Ever Gamma-Ray Burst". NASA. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Reddy, Francis (28 April 2009). "New Gamma-Ray Burst Smashes Cosmic Distance Record". NASA. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (25 May 2011). "Cosmic distance record "broken"". BBC News. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ^ Reddy, Francis (19 April 2010). "NASA's Swift Catches 500th Gamma-ray Burst". NASA. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Chang, Alicia (16 June 2011). "Black Hole Devours Star: Source Of Mysterious Flash In Distant Galaxy Determined". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ "Black hole eats star, triggers gamma-ray flash". Cosmos (Australian magazine). Agence France-Presse. 17 June 2011. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ Reddy, Francis (5 October 2012). "NASA's Swift Satellite Discovers a New Black Hole in our Galaxy". NASA. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Sbarufatti, Boris (17 September 2012). "Swift J174510.8-262411 (to be known as Sw J1745-26): 0.5 Crab and rising". The Astronomer's Telegram. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Belloni, Tomaso (3 October 2012). "Swift J174510.8-262411 in the hard intermediate state". The Astronomer's Telegram. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Young, Monica (10 May 2013). "A Cosmic Sleight of Hand". Sky & Telescope. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Reddy, Francis (3 May 2013). "NASA's Fermi, Swift See 'Shockingly Bright' Burst". NASA. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA's Swift Mission Observes Mega Flares from a Mini Star". NASA. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA Space Telescopes Pinpoint Elusive Brown Dwarf". NASA. 10 November 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Keivani, A.; et al. (26 September 2017). "IceCube-170922A: Swift-XRT observations". GCN Circulars. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA's Fermi, Swift Missions Enable a New Era in Gamma-ray Science". NASA. 20 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Further reading

[edit]- McKee, Maggie (6 April 2005). "Swift measures distance to gamma-ray bursts". New Scientist.

External links

[edit]- Swift website by NASA/GSFC

- Swift website by the UK Swift Science Data Centre

- Swift website by Pennsylvania State University

- Swift website by Sonoma State University

- Gamma-ray Burst Real-time Sky Map