Sulfonamide (medicine): Difference between revisions

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

===Antimicrobial=== |

===Antimicrobial=== |

||

{{Main|Dihydropteroate synthetase inhibitor}} |

{{Main|Dihydropteroate synthetase inhibitor}} |

||

In [[bacteria]], antibacterial sulfonamides act as [[competitive inhibitor]]s of the enzyme [[dihydropteroate synthetase|dihydropteroate synthetase (DHPS)]], an enzyme involved in [[folate synthesis]]. |

In [[bacteria]], antibacterial sulfonamides act as [[competitive inhibitor]]s of the enzyme [[dihydropteroate synthetase|dihydropteroate synthetase (DHPS)]], an enzyme involved in [[folate synthesis]]. As such, sulpha drugs can "starve" bacteria of folate, killing them. |

||

===Other uses=== |

===Other uses=== |

||

Revision as of 20:04, 5 June 2011

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2009) |

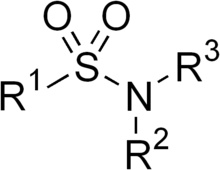

Sulfonamide or sulphonamide is the basis of several groups of drugs. The original antibacterial sulfonamides (sometimes called sulfa drugs or sulpha drugs) are synthetic antimicrobial agents that contain the sulfonamide group. Some sulfonamides are also devoid of antibacterial activity, e.g., the anticonvulsant sultiame. The sulfonylureas and thiazide diuretics are newer drug groups based on the antibacterial sulfonamides.[1]

Sulfa allergies are common,[2] hence medications containing sulfonamides are prescribed carefully. It is important to make a distinction between sulfa drugs and other sulfur-containing drugs and additives, such as sulfates and sulfites, which are chemically unrelated to the sulfonamide group, and do not cause the same hypersensitivity reactions seen in the sulfonamides.

Function

Antimicrobial

In bacteria, antibacterial sulfonamides act as competitive inhibitors of the enzyme dihydropteroate synthetase (DHPS), an enzyme involved in folate synthesis. As such, sulpha drugs can "starve" bacteria of folate, killing them.

Other uses

The sulfonamide chemical moiety is also present in other medications that are not antimicrobials, including thiazide diuretics (including hydrochlorothiazide, metolazone, and indapamide, among others), loop diuretics (including furosemide, bumetanide and torsemide) sulfonylureas (including glipizide, glyburide, among others), some COX-2 inhibitors (e.g. celecoxib) and acetazolamide.

Sulfasalazine, in addition to its use as an antibiotic, is also used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.

History

Sulfonamide drugs were the first antimicrobial drugs, and paved the way for the antibiotic revolution in medicine. The first sulfonamide, trade named Prontosil, was actually a prodrug. Experiments with Prontosil began in 1932 in the laboratories of Bayer AG, at that time a component of the huge German chemical trust IG Farben. The Bayer team believed that coal-tar dyes able to preferentially bind to bacteria and parasites might be used to target harmful organisms in the body. After years of fruitless trial-and-error work on hundreds of dyes, a team led by physician/researcher Gerhard Domagk (working under the general direction of Farben executive Heinrich Hoerlein) finally found one that worked: a red dye synthesized by Bayer chemist Josef Klarer that had remarkable effects on stopping some bacterial infections in mice.[3] The first official communication about the breakthrough discovery was not published until 1935, more than two years after the drug was patented by Klarer and his research partner Fritz Mietzsch. Prontosil, as Bayer named the new drug, was the first medicine ever discovered that could effectively treat a range of bacterial infections inside the body. It had a strong protective action against infections caused by streptococci, including blood infections, childbed fever, and erysipelas, and a lesser effect on infections caused by other cocci. However, it had no effect at all in the test tube, exerting its antibacterial action only in live animals. Later it was accidentally discovered by a French research team, led by Ernest Fourneau, at the Pasteur Institute that the drug was metabolized into two pieces inside the body, releasing from the inactive dye portion a smaller, colorless, active compound called sulfanilamide. The discovery helped establish the concept of "bioactivation" and dashed the German corporation's dreams of enormous profit; the active molecule sulfanilamide (or sulfa) had first been synthesized in 1906 and was widely used in the dye-making industry; its patent had since expired and the drug was available to anyone.[4]

The result was a sulfa craze.[5] For several years in the late 1930s, hundreds of manufacturers produced tens of thousands of tons of myriad forms of sulfa. This and nonexistent testing requirements led to the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster in the fall of 1937, during which at least 100 people were poisoned with diethylene glycol. This led to the passage of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act in 1938. As the first and only effective antibiotic available in the years before penicillin, sulfa drugs continued to thrive through the early years of World War II.[6] They are credited with saving the lives of tens of thousands of patients including Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jr. (son of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt) (in 1936) and Winston Churchill. Sulfa had a central role in preventing wound infections during the war. American soldiers were issued a first-aid kit containing sulfa pills and powder and were told to sprinkle it on any open wound.

During the years 1942 to 1943, Nazi doctors conducted sulfanilamide experiments on prisoners in concentration camps.[7][8]

The sulfanilamide compound is more active in the protonated form, which in case of the acid works better in a basic environment. The solubility of the drug is very low and sometimes can crystallize in the kidneys, due to its first pKa of around 10. This is a very painful experience so patients are told to take the medication with copious amounts of water. Newer compounds have a pKa of around 5–6 so the problem is avoided.

Many thousands of molecules containing the sulfanilamide structure have been created since its discovery (by one account, over 5,400 permutations by 1945), yielding improved formulations with greater effectiveness and less toxicity. Sulfa drugs are still widely used for conditions such as acne and urinary tract infections, and are receiving renewed interest for the treatment of infections caused by bacteria resistant to other antibiotics.

Preparation

Sulfonamides are prepared by the reaction of a sulfonyl chloride with ammonia or an amine. Certain sulfonamides (sulfadiazine or sulfamethoxazole) are sometimes mixed with the drug trimethoprim, which acts against dihydrofolate reductase.

List of sulfonamides

Antibiotics

- Short-acting

- Sulfamethoxazole

- Sulfisomidine (also known as sulfaisodimidine)

- Intermediate-acting

- Ophthalmologicals

- Dichlorphenamide (DCP)

- Dorzolamide

Diuretics

- Acetazolamide

- Bumetanide

- Chlorthalidone

- Clopamide

- Furosemide

- Hydrochlorothiazide (HCT, HCTZ, HZT)

- Indapamide

- Mefruside

- Metolazone

- Xipamide

Anticonvulsants

Dermatologicals

Other

- Celecoxib (COX-2 inhibitor)

- Darunavir (Protease Inhibitor)

- Probenecid (PBN)

- Sulfasalazine (SSZ)

- Sumatriptan (SMT)

Side effects

Sulfonamides have the potential to cause a variety of untoward reactions, including urinary tract disorders, haemopoietic disorders, porphyria and hypersensitivity reactions. When used in large doses, they may cause a strong allergic reaction. Two of the most serious are Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (also known as Lyell syndrome).[2]

Approximately 3% of the general population have adverse reactions when treated with sulfonamide antimicrobials. Of note is the observation that patients with HIV have a much higher prevalence, at about 60%.[10] People who have a hypersensitivity reaction to one member of the sulfonamide class are likely to have a similar reaction to others.

Hypersensitivity reactions are less common in non-antibiotic sulfonamides, and, though controversial, the available evidence suggests those with hypersensitivity to sulfonamide antibiotics do not have an increased risk of hypersensitivity reaction to the non-antibiotic agents.[11]

Two regions of the sulfonamide antibiotic chemical structure are implicated in the hypersensitivity reactions associated with the class.

- The first is the N1 heterocyclic ring, which causes a type I hypersensitivity reaction.

- The second is the N4 amino nitrogen that, in a stereospecific process, forms reactive metabolites that cause either direct cytotoxicity or immunologic response.

The non-antibiotic sulfonamides lack both of these structures.[12]

The most common manifestations of a hypersensitivity reaction to sulfa drugs are rash and hives. However, there are several life-threatening manifestations of hypersensitivity to sulfa drugs, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, agranulocytosis, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and fulminant hepatic necrosis, among others.[13]

See also

References

- ^ http://chemicalland21.com/info/SULFONAMIDE%20CLASS%20ANTIBIOTICS.htm

- ^ a b http://allergies.about.com/od/medicationallergies/a/sulfa.htm

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=S32TrACJa6kC&printsec=frontcover&dq=demon+under+the+microscope&hl=en&src=bmrr&ei=WijXTLGuHJO6sAOOqpSNCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/372460/history-of-medicine/35670/Sulfonamide-drugs

- ^ http://blogofbad.wordpress.com/2009/02/09/bad-health-elixir-sulfanilamide/

- ^ http://home.att.net/~steinert/wwii.htm#The%20Use%20of%20Sulfanilamide%20in%20World%20War%20II

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=5kkEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA81&ots=oPVGNNLzN4&dq=sulfa%20ravensbruck&pg=PA81#v=onepage&q=sulfa%20ravensbruck&f=false

- ^ http://www.adl.org/education/dimensions_19/section3/experiments.asp

- ^ http://www.onsettx.com/docs/clarifoam/Clarifoam%20EF%20Prescribing%20Information_PN%202603-pf_Rev%202.pdf

- ^

SA Tilles (2001). "Practical issues in the management of hypersensitivity reactions: sulfonamides". Southern Medical Journal. 94 (8): 817–24. PMID 11549195.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

CG Slatore; Tilles, S (2004). "Sulfonamide hypersensitivity". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 24 (3): 477–90, vii. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2004.03.011. PMID 15242722.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

CC Brackett; Singh, H; Block, JH (2004). "Likelihood and mechanisms of cross-allergenicity between sulfonamide antibiotics and other drugs containing a sulfonamide functional group". Pharmacotherapy. 24 (7): 856–70. doi:10.1592/phco.24.9.856.36106. PMID 15303450.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 13th Ed. McGraw-Hill Inc. 1994. p. 604.

External links

- http://www.nlm.nih.gov/cgi/mesh/2004/MB_cgi?field=entry&term=Sulfonamides - List of sulfonamides

- http://www.thomashager.net - author of "The Demon under the Microscope," a history of the discovery of the sulfa drugs

- http://www.lung.ca/tb/tbhistory/treatment/chemo.html - A History of the Fight Against Tuberculosis in Canada (Chemotherapy)

- http://www.nobel.se/medicine/laureates/1939/press.html - Presentation speech, Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine, 1939

- http://home.att.net/~steinert/wwii.htm - The History of WW II Medicine

- http://www.life.umd.edu/classroom/bsci424/Chemotherapy/AntibioticsHistory.htm - A history of antibiotics