Sugar glider: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 115.70.146.105 (talk) to last version by ClueBot NG |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

A sugar glider female gives birth to one (19%) or two (81%) babies (joeys) per litter. The gestation period is 15 to 17 days, after which the tiny joey (0.2 g) will crawl into a mother's pouch for further development. They are born with a continuous arc of cartilage in their shoulder girdle to provide support for climbing into the pouch. This structure breaks down immediately after birth.<ref>{{cite web|last=Antinoff, DVM, DABVP|first=Natalie|title=Practical anatomy and physical examination: Ferrets, rabbits, rodents, and other selected species (Proceedings)|url=http://veterinarycalendar.dvm360.com/avhc/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=638213&sk=&date=&%0A%09%09%09&pageID=5|publisher=CVC in Kansas City Proceedings|accessdate=11 November 2012}}</ref> |

A sugar glider female gives birth to one (19%) or two (81%) babies (joeys) per litter. The gestation period is 15 to 17 days, after which the tiny joey (0.2 g) will crawl into a mother's pouch for further development. They are born with a continuous arc of cartilage in their shoulder girdle to provide support for climbing into the pouch. This structure breaks down immediately after birth.<ref>{{cite web|last=Antinoff, DVM, DABVP|first=Natalie|title=Practical anatomy and physical examination: Ferrets, rabbits, rodents, and other selected species (Proceedings)|url=http://veterinarycalendar.dvm360.com/avhc/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=638213&sk=&date=&%0A%09%09%09&pageID=5|publisher=CVC in Kansas City Proceedings|accessdate=11 November 2012}}</ref> |

||

It is virtually unnoticeable that the female is pregnant until after the joey has climbed into her pouch and begins to grow, forming bumps in her pouch. Once in the pouch, the joey will attach itself to its mother's nipple, where it will stay for about 60 to 70 days. The mother can get pregnant while her joeys are still ip (in pouch) and hold the pregnancy until the pouch is available. The joey gradually spills out of the pouch until it falls out completely. It emerges virtually without fur, and the eyes will remain closed for another 12–14 days. During this time, the joey will begin to mature by growing fur and increasing gradually in size. It takes about two months for the offspring to be completely [[Weaning|weaned]], and at four months, the young glider is self-sufficient, however it will continue to live in the nest for ten months.<ref name="Hilltop"/> |

|||

=== Socialisation === |

=== Socialisation === |

||

Revision as of 18:53, 13 May 2014

| Sugar glider[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. breviceps

|

| Subspecies: | P.b. ariel, Gould 1842

P.b. breviceps, Waterhouse 1838 P.b. longicaudatus, Longman 1924 P.b. papuanus, Thomas 1888 |

| Binomial name | |

| Petaurus breviceps Waterhouse, 1839

| |

| |

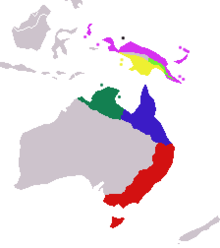

| Sugar glider natural range by subspecies: | |

| Synonyms | |

|

P. (Belideus) breviceps, Waterhouse 1839 | |

The sugar glider (Petaurus breviceps) is a small, omnivorous, arboreal and nocturnal gliding possum belonging to the marsupial infraclass. The common name refers to its preference for sugary nectarous foods and ability to glide through the air, much like a flying squirrel.[5] Due to convergent evolution, they have very similar appearance and habits to the flying squirrel, but are not closely related.[6] The scientific name, Petaurus breviceps, translates from Latin as "short-headed rope-dancer", a reference to their canopy acrobatics.[7]

The sugar glider is native to eastern and northern mainland Australia, and was introduced to Tasmania. It is also native to various islands in the region.

Distribution and habitat

Sugar gliders can be found throughout the northern and eastern parts of mainland Australia, and in Tasmania, Papua New Guinea and several associated isles, the Bismarck Archipelago, Louisiade Archipelago, and certain isles of Indonesia, Halmahera Islands of the North Moluccas.[8] The sugar glider was introduced to Tasmania in 1835.[9] This is supported by the absence of skeletal remains in subfossil bone deposits and the lack of an Aboriginal Tasmanian name for the animal.[5] They can be found in any forest where there is a suitable food supply, but most are commonly found in forests with eucalyptus trees. Being nocturnal, they sleep in their nests during the day and are active at night. During the night they hunt insects and small vertebrates, and feed on the sweet sap of certain species of eucalyptus, acacia and gum trees.[5]

They are arboreal, spending most of their lives in trees. When suitable habitats are present, sugar gliders can be seen 1 per 1,000 square metres, provided there are tree hollows available for shelter.[5]

Native owls (Ninox sp.)[10] are their primary predators; others in their range include kookaburras, goannas, snakes, and quolls.[9] Feral cats (Felis catus) also represent a significant threat.[9][10]

Appearance and anatomy

The sugar glider has a squirrel-like body with a long, partially (weakly)[11] prehensile tail. The males are larger than the females and have bald patches on their head and chest; their length from the nose to the tip of the tail is about 24 to 30 cm (12–13 inches, the body itself is approx. 5–6 inches). A sugar glider has a thick, soft fur coat that is usually blue-grey; some have been known to be yellow, tan or (rarely) albino.[a] A black stripe is seen from its nose to midway on its back. Its belly, throat, and chest are cream in colour.

Being nocturnal, its large eyes help it to see at night, and its ears swivel to help locate prey in the dark.

It has five digits on each foot, each having a claw, except for the opposable toe on the hind feet. Also on the hind feet, the second and third digits are partially syndactylous (fused together), forming a grooming comb.[11] Its most striking feature is the patagium, or membrane, that extends from the fifth finger to the first toe. When legs are stretched out, this membrane allows the sugar glider to glide a considerable distance.

There are four scent glands, located frontal (forehead), sternal (chest), and two paracloacal (associated with, but not part of the cloaca). These are used for marking purposes, mainly by the male. The frontal gland is easily seen on an adult male as a bald spot. The female has a marsupium (pouch) in the middle of her abdomen to carry offspring.[11]

Data averages[12]

- Head-body length: 170 mm (160–210)mm

- Tail length: 190 mm (165–210)mm

- Weight, males: 140 grams (115–160)g, females: 115 grams (95–135)g

- Heart rate: 200–300 beats per minute, respiration: 16–40 breaths per minute[13]

- Lifespan: in the wild, up to 9 years; typically up to 12 years in captivity;[14] in zoos, maximum reported is 17.8 years.[15]

Biology and behaviour

Gliding

The sugar glider is one of a number of volplane (gliding) possums in Australia. This remarkable ability to glide is achieved through flaps or membranes of loose skin (patagia) which extend between the fifth finger of each hand to the first toe of each foot. The animal launches itself from a tree, spreading its limbs to expose the gliding membranes. This creates an aerofoil enabling them to glide 50 metres or more.[16] This gliding flight is regulated by changing the curvature of the membrane or moving the legs and tail.[17]

This form of arboreal locomotion is typically used to travel from tree to tree; the species rarely descends to the ground. Gliding serves as an efficient means of both locating food and evading predators.[5]

Torpor

During the cold season, drought, or rainy nights, a sugar glider's activity is reduced. The animal may even become immobile and unresponsive due to torpor. This differs from hibernation in that torpor is usually a short-term daily cycle. In the winter season or drought, there is a decrease in food supply, which is a challenge for this marsupial because of the energy cost for the maintenance of its metabolism,[18] locomotion, and thermoregulation. With energetic constraints, the sugar glider will enter into daily torpor for 2–23 hours while in rest phase.[19] However, before entering torpor, a sugar glider will reduce activity and body temperature normally in order to lower energy expenditure and avoid torpor.[18][20]

Torpor, which is seen as an emergency measure, saves energy for the animal by allowing its body temperature to fall to a minimum of 10.4 °C (50.7 °F)[19] to 19.6 °C (67.3 °F).[21] When the food is scarce, as in winter, heat production is lowered in order to reduce energy expenditure.[22] With low energy and heat production, it is important for the sugar glider to peak its body mass by fat content in the autumn (May/June) in order to survive the following cold season. In the wild, sugar gliders enter into daily torpor more often than sugar gliders in captivity.[20][21]

Diet and nutrition

Sugar gliders are seasonally adapted omnivores with a wide variety of foods in their diet. In summer they are primarily insectivorous, and in the winter when insects (and other arthropods) are scarce, they are mostly exudativorous (feeding on acacia gum, eucalyptus sap, manna,[b] honeydew or lerp).[26] They are opportunistic feeders and can be carnivorous (preying mostly on lizards and small birds), and eat many other foods when available, such as nectar, acacia seeds, bird eggs, pollen, fungi and native fruits.[27][28]

Reproduction

The age of sexual maturity in sugar gliders varies slightly between the males and females. The males reach maturity at 4 to 12 months of age, while females require from 8 to 12 months. In the wild, sugar gliders breed once or twice a year depending on the climate and habitat conditions, while they can breed multiple times a year in captivity as a result of consistent living conditions and proper diet.[11]

A sugar glider female gives birth to one (19%) or two (81%) babies (joeys) per litter. The gestation period is 15 to 17 days, after which the tiny joey (0.2 g) will crawl into a mother's pouch for further development. They are born with a continuous arc of cartilage in their shoulder girdle to provide support for climbing into the pouch. This structure breaks down immediately after birth.[29]

Socialisation

Sugar gliders are highly social animals. They live in family groups or colonies consisting of up to seven adults, plus the current season's young which leave as soon as they are able to, all sharing a nest and defending their territory, an example of helping at the nest. They engage in social grooming, which in addition to improving hygiene and health, helps bond the colony and establish group identity.

A dominant adult male will mark his territory and members of the group with saliva and a scent produced by separate glands on the forehead and chest. Intruders who lack the appropriate scent marking are expelled violently.[5] Each colony defends a territory of about 2.5 acres where eucalyptus trees provide a staple food source. Within the colony, typically no fighting takes place beyond threatening behaviour.[30]

Conservation

John Gould, 1861

The sugar glider is not considered endangered, and its conservation rank is "Least Concern (LC)" on the IUCN Red List.[31] Despite the loss of natural habitat in Australia over the last 200 years, it is adaptable and capable of living in small patches of remnant bush, particularly if it does not have to cross large expanses of cleared land to reach them. However, several close relatives are endangered, particularly Leadbeater's Possum and the Mahogany Glider.

Conservation in Australia is enacted at the federal, state and local levels, where sugar gliders are protected as a native species. The central conservation law in Australia is the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).[32] The National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 is an example of conservation law in the state of South Australia, where it is legal to keep (only) one sugar glider without a permit, provided it was acquired legally from a source with a permit. A permit is required to obtain or possess more than one glider, or if one wants to sell or give away any glider in their possession. It is illegal to capture or sell wild sugar gliders without a permit.[33]

In captivity

In captivity, they can suffer from calcium deficiencies if not fed an adequate diet. A lack of calcium in the diet causes the body to leach calcium from the bones, with the hind legs first to show noticeable dysfunction.[34] Calcium to phosphorus ratios should be 2:1 to prevent hypocalcemia, sometimes known as hind leg paralysis (HLP).[35] Their diet should be 50% insects (gut-loaded) or other sources of protein, 25% fruit and 25% vegetables.[36] Some of the more recognised diets are Bourbon's Modified Leadbeaters (BML),[37] High Protein Wombaroo (HPW)[38] and various calcium rich diets with Leadbeaters Mixture (LBM).[39]

As a pet

Around the world, the sugar glider is popular as an exotic pet. It is also one of the most commonly traded wild animals in the illegal pet trade, where animals are plucked directly from their natural habitats.[40]

In Australia, sugar gliders can be kept in Victoria, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. However, they are not allowed to be kept as pets in Western Australia, New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland or Tasmania.[41][42]

Sugar gliders are popular as pets in the United States, where they are bred in large numbers. Most states and cities allow sugar gliders as pets, with some exceptions including California,[43] Hawaii,[44] and Alaska. In 2014, Massachusetts changed its law, allowing sugar gliders to be kept as pets.[45] Some other states require permits or licensing.[46] Many states also require permits and/or licensing for breeding large numbers of sugar gliders.

Taxonomy

Further taxonomic study is needed because P. breviceps might be composed of more than one species.[note 4]

| Taxon | Name | Subspecies of Petaurus breviceps[48] | Other Petaurus species | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Eukaryota | P. b. breviceps (Waterhouse, 1839) | P. abidi (Northern Glider) | ||

| Kingdom | Animalia | P. b. longicaudatus (Longman, 1924) | P. australis (Yellow-bellied Glider) | ||

| Phylum | Chordata | P. b. ariel (Gould, 1842) | P. biacensis (Biak Glider) | ||

| Class | Mammalia | P. b. papuanus (Thomas, 1888) | P. gracilis (Mahogany Glider) | ||

| Legion | Cladotheria | P. norfolcensis (Squirrel Glider)[49] | |||

| Cohort | Marsupialia | ||||

| Order | Diprotodontia | ||||

| Family | Petauridae | ||||

| Genus | Petaurus | ||||

| Specific name | breviceps[49] |

Notes

- ^ Tate & Archbold, 1935; subspecies P. b. tafa considered a synonym of species P. breviceps[3]

- ^ P. b. flavidus (Tate and Archbold, 1935) considered a synonym of P. b. papuanus (Thomas 1888)

- ^ Subspecies (former) P. b. biacensis provisionally considered species: P. biacensis (Biak Glider). "Helgen (2007) states that Petaurus biacensis is likely to be conspecific with P. breviceps. P. biacensis appears to differ from the latter mainly by having a higher incidence of melanism (Helgen 2007). We provisionally retain P. biacensis as a separate species pending further taxonomic work, thus following what has become standard treatment (e.g., Flannery 1994, 1995; Groves 2005)."[4]

- ^ "An undescribed form from Tifalmin, west of the Sepik, is very distinct (Colgan and Flannery, 1992). Gliders from Goodenough, Fergusson and Normanby Isls (D'Entrecasteaux group), Papua New Guinea, usually identified as belonging to this species, are very distinct morphologically, if not electrophoretically (Flannery, 1994a)."[47]

- Footnotes

- ^ Domestic in-breeding of recessive genetic phenotype defects can produce other colour variations not found in nature, such as an all-white leucistic heterozygote.

- ^ When dried, an exudate (such as sap) becomes crystallized and is referred to as manna,[23][24] which is consumed by sugar gliders.[25]

References

- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Template:IUCN2008 Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- ^ Subspecies Sheet | Mammals'Planet. Planet-mammiferes.org. Retrieved on 2014-04-19.

- ^ Leary, T., Wright, D., Hamilton, S., Singadan, R., Menzies, J., Bonaccorso, F., Salas, L., Dickman, C. & Helgen, K. (2008). Petaurus biacensis. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2.

- ^ a b c d e f DPIPWE – Sugar Glider

- ^ "Analogy: Squirrels and Sugar Gliders". Understanding Evolution. The University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ "Sugar Glider, Petaurus breviceps". Parks & Wildlife Service, Tasmania Online. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ Dickman, Ronald M. Nowak ; introduction by Christopher R. (2005). Walker's marsupials of the world. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 190. ISBN 0801882222.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Wildlife – Sugar Glider". Wildlife Queensland. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ a b Smith, Meredith J. (13 June 1973). "Petaurus breviceps" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 30. The American Society of Mammalogists: 1–5. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d Pye, BVSc, MSc, Geoffrey W. "A guide to medicine and surgery in sugar gliders". Hilltop Animal Hospital. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Wildlife Queensland – Sugar Glider". Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ "Basic Health Care Information / General Wellness Exam". Sugar Glider Vet. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ "Sugar Glider, Petaurus breviceps". Parks & Wildlife Service, Tasmania Online. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ de Magalhaes, J. P., Budovsky, A., Lehmann, G., Costa, J., Li, Y., Fraifeld, V., Church, G. M. (2009) "The Human Ageing Genomic Resources: online databases and tools for biogerontologists." Aging Cell 8(1):65–72. "AnAge entry for Petaurus breviceps".

- ^ Strahan, the Australian Museum ; edited by Ronald (1983). Complete book of Australian mammals : the national photographic index of Australian wildlife (1. publ. ed.). [Sidney]: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0207144540.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Sugar Glider Fun Facts". Drsfostersmith.com. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ a b Geiser, Fritz (15 October 2003). "Metabolic Rate and Body Temperature Reduction During Hibernation and Daily Torpor". Annual Review of Physiology. 66 (1): 239–274. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.115105.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ a b Körtner, Gerhard (2000). "Torpor and activity patterns in free-ranging sugar gliders Petaurus breviceps (Marsupialia)". Oecologia. 123 (3): 350–357. doi:10.1007/s004420051021.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Christian, Nereda (2007). "To use or not to use torpor? Activity and body temperature as predictors". Naturwissenschaften. 94 (6): 483–487. doi:10.1007/s00114-007-0215-5.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Geiser, Fritz (2007). "Thermal biology, torpor and behaviour in sugar gliders: a laboratory-field comparison". Journal of Comparative Physiology B: Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology. 177 (5): 495–501. doi:10.1007/s00360-007-0147-6.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Seasonal changes in the thermoenergetics of the marsupial sugar glider, Petaurus breviceps". J. Comp. Physiol. B, Biochem. Syst. Environ. Physiol. 171 (8): 643–50. November 2001. PMID 11765973.

- ^ "manna". WordNet Search – 3.1. WordNet. Princeton University. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

(n) manna (hardened sugary exudation of various trees) : Synset (semantic) relations, direct hypernym (n) sap (a watery solution of sugars, salts, and minerals that circulates through the vascular system of a plant)

- ^ Pickert...], Executive ed.: Joseph P. (1992). The American heritage dictionary of the English language (4th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 1065. ISBN 0395825172.

manna n. 4. The dried exudate of certain plants

- ^ Cianciolo, Janine M. , DVM. "Sugar Glider Nutrition". Past Newsletters. SunCoast Sugar Gliders.

Sugar gliders eat manna in the wild. Manna is a crusty sugar left from where sap flowed from a wound in a tree trunk or branch.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Sugar Glider Diet". Sugar Glider Diet Archives. Sugar Glider Cage. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ McLeod, DVM, Lianne. "Feeding Sugar Gliders / Nutritional Needs and Sample Diets". About.com. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Natural Diet". Gliderpedia. SugarGlider.com. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Antinoff, DVM, DABVP, Natalie. "Practical anatomy and physical examination: Ferrets, rabbits, rodents, and other selected species (Proceedings)". CVC in Kansas City Proceedings. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pasatta, J. (1999). "Petaurus breviceps" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed November 10, 2012

- ^ Petaurus breviceps (Sugar Glider). Iucnredlist.org (2008-06-30). Retrieved on 2014-04-19.

- ^ Biodiversity Conservation. Environment.gov.au. Retrieved on 2014-04-19.

- ^ South Australian Legislation. Legislation.sa.gov.au. Retrieved on 2014-04-19.

- ^ "Hind Leg Paralysis". SugarGlider.com. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2007.01.001, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.cvex.2007.01.001instead. - ^ Conservation and natural resources, 1995 Mammals of Victoria, ed. by Menkhorst. P., Oxford University Press, South Melbourne ISBN 0-19-553733-5

- ^ "Original BML Diet – Bourbon's Modified Leadbeater's Recipe for Sugar Gliders". Sweet-Sugar-Gliders.com. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ "Sugar Glider HPW Diet – High Protein Wombaroo Recipe". Sweet-Sugar-Gliders.com. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ "Original Leadbeaters Diet Recipe – Taronga Zoo Diet for Sugar Gliders". Sweet-Sugar-Gliders.com. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "Insider the Exotic Pet Trade: Fatal Attractions". discovery.com. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ "DixiGliders".

- ^ Wildlife – Queensland Gliders. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2014-04-19.

- ^ "Illegal pets in California". Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ "Illegal pets in Hawaii". Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ MacCallum, Wayne F. , Director. "Notice of Changes In the Law Relative to Wildlife that May be Sold By Licensed Pet Shops or Kept as Pets in Massachusetts" (PDF). Division of Fisheries & Wildlife. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Summary of State Laws Relating to Private Possession of Exotic Animals". Born Free USA. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Salas, L., Dickman, C., Helgen, K., Winter, J., Ellis, M., Denny, M., Woinarski, J., Lunney, D., Oakwood, M., Menkhorst, P. & Strahan, R. 2008. Petaurus breviceps. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 25 October 2012.

- ^ "Petaurus breviceps Waterhouse, 1838". Namebank Record Detail. uBio. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

Classification according to: Species2000 and ITIS Catalogue of Life: 2008

- ^ a b Petaurus breviceps (Australian sugar glider). Zipcodezoo.com. Retrieved on 2014-04-19.

Bibliography

- Beld, John van den (1992). Nature of Australia : a portrait of the island continent (Revised ed.). Sydney: Collins Australia. ISBN 0-7333-0241-6.

- Cayley, [by] Ellis Troughton ; with twenty-five plates in colour by Neville W. (1973). Furred animals of Australia (Rev. and abridged ed.). Sydney: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-12256-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fry, [by] W.D.L. Ride. With drawings by Ella (1970). A guide to the native mammals of Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195502523.

- Morcombe, Michael (1974). Mammals of Australia. Sydney: Australian Universities Press. ISBN 0-7249-0017-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Russel, Rupert Russel illustr. by Kay (1980). Spotlight on possums. Queensland, St . Lucia: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 0-7022-1478-7.

- Serventy, [by] Vincent (1977). Wildlife of Australia (Rev. ed.). West Melbourne, Vic.: Thomas Nelson (Australia). ISBN 0-17-005168-4.

- Westmacott, Leonard Cronin ; illustrated by Marion (1991). Key guide to Australian mammals. Balgowlah, NSW: Reed Books. ISBN 0-7301-0355-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Sugar glider — Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland

- Gliders in the Spotlight — Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland

- Basic Sugar Glider information — Australian Fauna

- Information about the Sugar Glider — Tasmania Parks & Wildlife Service

- ITIS report: Petaurus breviceps — Taxon classification verified by ITIS

- Petaurus breviceps — Animal Diversity Web

- VIDEOS: sugar gliders in the wild on ARKive.org — BBC Natural History Unit

- Enlargement of Petaurus breviceps skull — Museum Victoria, Bioinformatics (photo showing sugar gliders' unusual dentition)

- Sugar Glider Addicts Anonymous — Information About Sugar Gliders Without The Sugar Coating

- Use dmy dates from June 2011

- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Gliding possums

- Animals described in 1839

- Mammals of New South Wales

- Mammals of Papua New Guinea

- Mammals of Queensland

- Mammals of South Australia

- Mammals of the Northern Territory

- Mammals of Victoria (Australia)

- Mammals of Western Australia

- Mammals of Western New Guinea

- Domesticated animals

- Pollinators