Suburb

A suburb (more broadly suburban area) is an area within a metropolitan area which is predominantly residential and within commuting distance of a large city.[1] Suburbs can have their own political or legal jurisdictions, especially in the United States, but this is not always the case, especially in the United Kingdom, where most suburbs are located within the administrative boundaries of cities.[2] In most English-speaking countries, suburban areas are defined in contrast to central city or inner city areas, but in Australian English and South African English, suburb has become largely synonymous with what is called a "neighborhood" in the U.S.[3] Due in part to historical trends such as white flight, some suburbs in the United States have a higher population and higher incomes than their nearby inner cities.[4]

In some countries, including India, China, New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom, and parts of the United States, new suburbs are routinely annexed by adjacent cities due to urban sprawl. In others, such as Morocco, France, and much of the United States, many suburbs remain separate municipalities or are governed locally as part of a larger metropolitan area such as a county, district or borough. In the United States, regions beyond the suburbs are known as "exurban areas" or exurbs; exurbs have less population density than suburbs, but still more than rural areas. Suburbs and exurbs are sometimes linked to the nearby city economically, particularly by commuters.

Suburbs first emerged on a large scale in the 19th and 20th centuries, as a result of improved rail and road transport, which led to an increase in commuting.[5] In general, they are less densely populated than inner city neighborhoods within the same metropolitan area, and most residents routinely commute to city centers or business districts via private vehicles or public transit; however, there are many exceptions, including industrial suburbs, planned communities, and satellite cities. Suburbs tend to proliferate around cities that have an abundance of adjacent flat land.[6]

Etymology and usage

[edit]The English word is derived from the Old French subburbe, which is in turn derived from the Latin suburbium, formed from sub (meaning "under" or "below") and urbs ("city"). The first recorded use of the term in English according to the Oxford English Dictionary[7] appears in Middle English c. 1350 in the manuscript of the Midlands Prose Psalter,[8] in which the form suburbes is used.

Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa

[edit]

In Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, suburban areas (in the wider sense noted in the lead paragraph) have become formalized as geographic subdivisions of a city and are used by postal services in addressing. In rural areas in both countries, their equivalents are called localities (see suburbs and localities). The terms inner suburb and outer suburb are used to differentiate between the higher-density areas in proximity to the city center (which would not be referred to as 'suburbs' in most other countries), and the lower-density suburbs on the outskirts of the urban area. The term 'middle suburbs' is also used. Inner suburbs, such as Te Aro in Wellington, Eden Terrace in Auckland, Prahran in Melbourne and Ultimo in Sydney, are usually characterized by higher density apartment housing and greater integration between commercial and residential areas.

North America

[edit]In the United States and Canada, suburb can refer either to an outlying residential area of a city or town or to a separate municipality or unincorporated area outside a town or city.[citation needed][9]

Although a majority of Americans regard themselves as residents of suburban communities, the federal government of the United States has no formal definition for what constitutes a suburb in the United States, leaving its precise meaning disputed.[10][11]

In Canada, the term may also be used in the British sense, especially as cities annex formerly outlying areas.[citation needed]

United Kingdom and Ireland

[edit]

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, the term suburb simply refers to a residential area outside the city centre, regardless of administrative boundaries.[5] Suburbs, in this sense, can range from areas that seem more like residential areas of a city proper to areas separated by open countryside from the city centre. In large cities such as London and Leeds, many suburbs are formerly separate towns and villages that have been absorbed during a city's expansion, such as Ealing, Bromley, and Guiseley. In Ireland, this can be seen in the Dublin suburban areas of Swords, Blanchardstown, and Tallaght.

History

[edit]The history of suburbia is part of the study of urban history, which focuses on the origins, growth, diverse typologies, culture, and politics of suburbs, as well as on the gendered and family-oriented nature of suburban space.[12][13] Many people have assumed that early-20th-century suburbs were enclaves for middle-class whites, a concept that carries tremendous cultural influence yet is actually stereotypical. Some suburbs are based on a society of working-class and minority residents, many of whom want to own their own house. Meanwhile, other suburbs instituted "explicitly racist" policies to deter people deemed as "other", a practice most common in the United States in contrast to other countries around the world.[14] Mary Corbin Sies argues that it is necessary to examine how "suburb" is defined as well as the distinction made between cities and suburbs, geography, economic circumstances, and the interaction of numerous factors that move research beyond acceptance of stereotyping and its influence on scholarly assumptions.[15]

Early history

[edit]The earliest appearance of suburbs coincided with the spread of the first urban settlements. Large walled towns tended to be the focus around which smaller villages grew up in a symbiotic relationship with the market town. The word suburbani was first employed by the Roman statesman Cicero in reference to the large villas and estates built by the wealthy patricians of Rome on the city's outskirts.

Towards the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty, until 190 AD, when Dong Zhuo razed the city, the capital Luoyang was mainly occupied by the emperor and important officials; the city's people mostly lived in small cities right outside Luoyang, which were suburbs in all but name.[16]

As populations grew during the Early Modern Period in Europe, towns swelled with a steady influx of people from the countryside. In some places, nearby settlements were swallowed up as the main city expanded. The peripheral areas on the outskirts of the city were generally inhabited by the very poorest.[17]

Origins of the modern suburb

[edit]Due to the rapid migration of the rural poor to the industrializing cities of England in the late 18th century, a trend in the opposite direction began to develop, whereby newly rich members of the middle classes began to purchase estates and villas on the outskirts of London. This trend accelerated through the 19th century, especially in cities like London and Birmingham that were growing rapidly, and the first suburban districts sprung up around downtowns to accommodate those who wanted to escape the squalid conditions of the industrial towns. Initially, such growth came along rail lines in the form of ribbon developments, as suburban residents could commute via train to downtown for work. In Australia, where Melbourne would soon become the second-largest city in the British Empire,[18] the distinctively Australasian suburb, with its loosely aggregated quarter-acre sections, developed in the 1850s[19] and eventually became a component of the Australian Dream.

Toward the end of the century, with the development of public transit systems such as the underground railways, trams and buses, it became possible for the majority of a city's population to reside outside the city and to commute into the center for work.[17]

By the mid-19th century, the first major suburban areas were springing up around London as the city (then the largest in the world) became more overcrowded and unsanitary. A major catalyst for suburban growth was the opening of the Metropolitan Railway in the 1860s. The line later joined the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the suburbs of Middlesex.[20] The line reached Harrow in 1880.

Unlike other railway companies, which were required to dispose of surplus land, London's Met was allowed to retain such land that it believed was necessary for future railway use.[note 1] Initially, the surplus land was managed by the Land Committee,[22] and, from the 1880s, the land was developed and sold to domestic buyers in places like Willesden Park Estate, Cecil Park, near Pinner and at Wembley Park.

In 1912 it was suggested that a specially formed company should take over from the Surplus Lands Committee and develop suburban estates near the railway.[23] However, World War I (1914–1918) delayed these plans until 1919, when, with the expectation of a postwar housing-boom,[24] Metropolitan Railway Country Estates Limited (MRCE) formed. MRCE went on to develop estates at Kingsbury Garden Village near Neasden, Wembley Park, Cecil Park and Grange Estate at Pinner and the Cedars Estate at Rickmansworth and to found places such as Harrow Garden Village.[24][25]

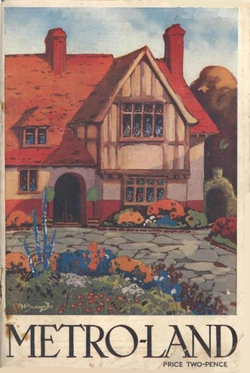

The Met's marketing department coined the term Metro-land in 1915 when the Guide to the Extension Line became the Metro-land guide, priced at 1d. This promoted the land served by the Met for the walker, visitor and later the house-hunter.[23] Published annually until 1932 (the last full year of independence for the Met), the guide extolled the benefits of "The good air of the Chilterns", using language such as "Each lover of Metroland may well have his own favorite wood beech and coppice — all tremulous green loveliness in Spring and russet and gold in October".[26] The dream as promoted involved a modern home in beautiful countryside with a fast railway-service to central London.[27] By 1915 people from across London had flocked to live the new suburban dream in large newly built areas across north-west London.[28]

Interwar suburban expansion in England

[edit]

Suburbanization in the interwar period was heavily influenced by the garden city movement of Ebenezer Howard and the creation of the first garden suburbs at the turn of the 20th century.[29] The first garden suburb was developed through the efforts of social reformer Henrietta Barnett and her husband; inspired by Ebenezer Howard and the model housing development movement (then exemplified by Letchworth garden city), as well as the desire to protect part of Hampstead Heath from development, they established trusts in 1904 which bought 243 acres of land along the newly opened Northern line extension to Golders Green and created the Hampstead Garden Suburb. The suburb attracted the talents of architects including Raymond Unwin and Sir Edwin Lutyens, and it ultimately grew to encompass over 800 acres.[30]

During World War I, the Tudor Walters Committee was commissioned to make recommendations for the post war reconstruction and housebuilding. In part, this was a response to the shocking lack of fitness amongst many recruits during World War One, attributed to poor living conditions; a belief summed up in a housing poster of the period "you cannot expect to get an A1 population out of C3 homes" – referring to military fitness classifications of the period.

The committee's report of 1917 was taken up by the government, which passed the Housing, Town Planning, &c. Act 1919, also known as the Addison Act after Christopher Addison, the then Minister for Housing. The Act allowed for the building of large new housing estates in the suburbs after the First World War,[31] and marked the start of a long 20th century tradition of state-owned housing, which would later evolve into council estates.

The Report also legislated on the required, minimum standards necessary for further suburban construction; this included regulation on the maximum housing density and their arrangement, and it even made recommendations on the ideal number of bedrooms and other rooms per house. Although the semi-detached house was first designed by the Shaws (a father and son architectural partnership) in the 19th century, it was during the suburban housing boom of the interwar period that the design first proliferated as a suburban icon, being preferred by middle-class home owners to the smaller terraced houses.[32] The design of many of these houses, highly characteristic of the era, was heavily influenced by the Art Deco movement, taking influence from Tudor Revival, chalet style, and even ship design.

Within just a decade suburbs dramatically increased in size. Harrow Weald went from just 1,500 to over 10,000 while Pinner jumped from 3,000 to over 20,000. During the 1930s, over 4 million new suburban houses were built, the 'suburban revolution' had made England the most heavily suburbanized country in the world, by a considerable margin.[5]

North America

[edit]Boston and New York City spawned the first major suburbs. The streetcar lines in Boston and the rail lines in Manhattan made daily commutes possible.[33] No metropolitan area in the world was as well served by railroad commuter lines at the turn of the twentieth century as New York, and it was the rail lines to Westchester from the Grand Central Terminal commuter hub that enabled its development. Westchester's true importance in the history of American suburbanization derives from the upper-middle class development of villages including Scarsdale, New Rochelle and Rye serving thousands of businessmen and executives from Manhattan.[34]

Postwar suburban expansion

[edit]The suburban population in North America exploded during the post-World War II economic expansion. Returning veterans wishing to start a settled life moved in masses to the suburbs. Levittown developed as a major prototype of mass-produced housing. Due to the influx of people in these suburban areas, the amount of shopping centers began to increase as suburban America took shape. These malls helped supply goods and services to the growing urban population. Shopping for different goods and services in one central location without having to travel to multiple locations, helped to keep shopping centers a component of these newly designed suburbs which were booming in population. The television helped contribute to the rise of shopping centers by allowing for additional advertisement through the medium in addition to creating a desire among consumers to buy products that are shown being used in suburban life on various television programs. Another factor that led to the rise of these shopping centers was the building of many highways. The Highway Act of 1956 helped to fund the building of 64,000 kilometers across the nation by having 26 billion dollars on hand, which helped to link many more to these shopping centers with ease.[35] These newly built shopping centers, which were often large buildings full of multiple stores, and services, were being used for more than shopping, but as a place of leisure and a meeting point for those who lived within suburban America at this time. These centers thrived offering goods and services to the growing populations in suburban America. In 1957, 940 shopping centers were built and this number more than doubled by 1960 to keep up with the demand of these densely populated areas.[36]

Housing

[edit]

Very little housing had been built during the Great Depression and World War II, except for emergency quarters near war industries. Overcrowded and inadequate apartments was the common condition. Some suburbs had developed around large cities where there was rail transportation to the jobs downtown. However, the real growth in suburbia depended on the availability of automobiles, highways, and inexpensive housing.[37] The population had grown, and the stock of family savings had accumulated the money for down payments, automobiles and appliances. The product was a great housing boom. Whereas an average of 316,000 new non-farm housing units were constructed from the 1930s through 1945, there were 1,450,000 constructed annually from 1946 through 1955.[38] The G.I. Bill guaranteed low-cost loans for veterans, with very low down payments, and low interest rates.

With 16 million eligible veterans, the opportunity to buy a house was suddenly at hand. In 1947 alone, 540,000 veterans bought one; their average price was $7300. The construction industry kept prices low by standardization—for example, standardizing sizes for kitchen cabinets, refrigerators and stoves allowed for mass production of kitchen furnishings. Developers purchased empty land just outside the city, installed tract houses based on a handful of designs, and provided streets and utilities, while local public officials raced to build schools.[39] The most famous development was Levittown, in Long Island just east of New York City. It offered a new house for $1000 down and $70 a month; it featured three bedrooms, a fireplace, a gas range and gas furnace, and a landscaped lot of 75 by 100 feet, all for a total price of $10,000. Veterans could get one with a much lower down payment.[40]

At the same time, African Americans were rapidly moving north and west for better jobs and educational opportunities than were available to them in the segregated South. Their arrival in Northern and Western cities en masse, in addition to being followed by race riots in several large cities such as Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Detroit, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., further stimulated white suburban migration. The growth of the suburbs was facilitated by the development of zoning laws, redlining and numerous innovations in transport. Redlining and other discriminatory measures built into federal housing policy furthered the racial segregation of postwar America–for example, by refusing to insure mortgages in and near African-American neighborhoods. The government's efforts were primarily designed to provide housing to White middle-class and lower-middle-class families. African Americans and other people of color largely remained concentrated within decaying cores of urban poverty creating a phenomenon known as white flight.[41]

After World War II, the availability of FHA loans stimulated a housing boom in American suburbs. In the older cities of the northeast U.S., streetcar suburbs originally developed along train or trolley lines that could shuttle workers into and out of city centers where the jobs were located. This practice gave rise to the term "bedroom community", meaning that most daytime business activity took place in the city, with the working population leaving the city at night for the purpose of going home to sleep.

Economic growth in the United States encouraged the suburbanization of American cities that required massive investments for the new infrastructure and homes. Consumer patterns were also shifting at this time, as purchasing power was becoming stronger and more accessible to a wider range of families. Suburban houses also brought about needs for products that were not needed in urban neighborhoods, such as lawnmowers and automobiles. During this time commercial shopping malls were being developed near suburbs to satisfy consumers' needs and their car–dependent lifestyle.[42]

Zoning laws also contributed to the location of residential areas outside of the city center by creating wide areas or "zones" where only residential buildings were permitted. These suburban residences are built on larger lots of land than in the central city. For example, the lot size for a residence in Chicago is usually 125 feet (38 m) deep,[43] while the width can vary from 14 feet (4.3 m) wide for a row house to 45 feet (14 m) wide for a large stand–alone house.[citation needed] In the suburbs, where stand–alone houses are the rule, lots may be 85 feet (26 m) wide by 115 feet (35 m) deep, as in the Chicago suburb of Naperville.[citation needed] Manufacturing and commercial buildings were segregated in other areas of the city.

Alongside suburbanization, many companies began locating their offices and other facilities in the outer areas of the cities, which resulted in the increased density of older suburbs and the growth of lower density suburbs even further from city centers. An alternative strategy is the deliberate design of "new towns" and the protection of green belts around cities. Some social reformers attempted to combine the best of both concepts in the garden city movement.[44]

In the U.S., 1950 was the first year that more people lived in suburbs than elsewhere.[45] In the U.S., the development of the skyscraper and the sharp inflation of downtown real estate prices also led to downtowns being more fully dedicated to businesses, thus pushing residents outside the city center.

Worldwide

[edit]While suburbs are often associated with the middle classes, in many parts of the developed world, suburbs can be economically distressed areas, inhabited by higher proportions of recent immigrants, with higher delinquency rates and social problems, reminiscent of the inner cities of the U.S. Examples include the banlieues of France, or the concrete suburbs of Sweden, even if the suburbs of these countries also include middle-class and upper-class neighborhoods that often consist of single-family houses.

Africa

[edit]Following the growth of the middle class due to African industrialization, the development of middle class suburbs has boomed since the beginning of the 1990s, particularly in cities such as Cairo, Nairobi, Johannesburg, and Lagos.

In an illustrative case of South Africa, RDP housing has been built. In much of Soweto, many houses are American in appearance, but are smaller, and often consist of a kitchen and living room, two or three bedrooms, and a bathroom. However, there are more affluent neighborhoods, more comparable to American suburbs, particularly east of the FNB ("Soccer City") Stadium and south of the city in areas like Eikenhof, where the "Eye of Africa" planned community exists.[46] This master-planned community is nearly indistinguishable from the most amenity-rich resort-style American suburbs in Florida, Arizona, and California, complete with a golf course, resort pool, equestrian facility, 24-hour staffed gates, gym, and BMX track, as well as several tennis, basketball, and volleyball courts.[47]

In Cape Town, there is a distinct European style originating from European influence during the mid-1600s when the Dutch settled the Cape. Houses like these are called Cape Dutch Houses and can be found in the affluent suburbs of Constantia and Bishopscourt.

Australia

[edit]Large cities like Sydney and Melbourne had streetcar suburbs in the tram era. With the automobile, the Australian usage came about as outer areas were quickly surrounded in fast-growing cities, but retained the appellation suburb; the term was eventually applied to neighborhoods in the original core as well. In Australia, Sydney's urban sprawl has occurred predominantly in the Western Suburbs. The locality of Olympic Park was designated an official suburb in 2009.[48]

Bangladesh

[edit]Bangladesh has multiple suburbs, Uttara & Ashulia to name a few. However, most suburbs in Dhaka are different from the ones in Europe & Americas. Most suburbs in Bangladesh are filled with high-rise buildings, paddy fields, and farms, and are designed more like rural villages.

Canada

[edit]Canada is an urbanized nation where over 80% of the population lives in urban areas (loosely defined), and roughly two-thirds live in one of Canada's 33 census metropolitan areas (CMAs) with a population of over 100,000. However, of this metropolitan population, in 2001 nearly half lived in low-density neighborhoods, with only one in five living in a typical "urban" neighborhood. The percentage living in low-density neighborhoods varied from a high of nearly two-thirds of Calgary CMA residents (67%), to a low of about one-third of Montréal CMA residents (34%).

Large cities in Canada acquired streetcar suburbs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modern Canadian suburbs tend to be less automobile-centric than those in the United States, and public transit use is encouraged but can be notably unused.[49] Throughout Canada, there are comprehensive plans in place to curb sprawl.

Population and income growth in Canadian suburbs had tended to outpace growth in core urban or rural areas, but in many areas, this trend has now reversed. The suburban population increased by 87% between 1981 and 2001, well ahead of urban growth.[50] The majority of recent population growth in Canada's three largest metropolitan areas (Greater Toronto, Greater Montréal, and Greater Vancouver) has occurred in non-core municipalities. This trend is also beginning to take effect in Vancouver, and to a lesser extent, Montréal. In certain cities, particularly Edmonton and Calgary, suburban growth takes place within the city boundaries as opposed to in bedroom communities. This is due to annexation and a large geographic footprint within the city borders.

Calgary is unusual among Canadian cities because it has developed as a unicity – it has annexed most of its surrounding towns and large amounts of undeveloped land around the city. As a result, most of the communities that Calgarians refer to as "suburbs" are actually inside the city limits.[51] In the 2016 census, the City of Calgary had a population of 1,239,220, whereas the Calgary Metropolitan Area had a population of 1,392,609, indicating the vast majority of people in the Calgary CMA lived within the city limits. The perceived low population density of Calgary largely results from its many internal suburbs and the large amount of undeveloped land within the city. The city actually has a policy of densifying its new developments.[52]

China

[edit]In China, the term suburb is new, although suburbs are already being constructed rapidly. Chinese suburbs mostly consist of rows upon rows of apartment blocks and condos that end abruptly into the countryside.[53][54] Also new town developments are extremely common. Single family suburban homes tend to be similar to their Western equivalents; although primarily outside Beijing and Shanghai, also mimic Spanish and Italian architecture.[55]

Hong Kong

[edit]In Hong Kong, however, suburbs are mostly government-planned new towns containing numerous public housing estates. However, other new towns also contain private housing estates and low density developments for the upper classes.

Italy

[edit]In the illustrative case of Rome, Italy, in the 1920s and 1930s, suburbs were intentionally created ex novo to give lower classes a destination, in consideration of the actual and foreseen massive arrival of poor people from other areas of the country. Many critics have seen in this development pattern (which was circularly distributed in every direction) also a quick solution to a problem of public order (keeping the unwelcome poorest classes together with the criminals, in this way better controlled, comfortably remote from the elegant "official" town). On the other hand, the expected huge expansion of the town soon effectively covered the distance from the central town, and now those suburbs are completely engulfed by the main territory of the town. Other newer suburbs (called exurbs) were created at a further distance from them.[citation needed]

Japan

[edit]In Japan, the construction of suburbs has boomed since the end of World War II and many cities are experiencing the urban sprawl effect.

Latin America

[edit]In Mexico, suburbs are generally similar to their United States counterparts. Houses are made in many different architectural styles which may be of European, American and International architecture and which vary in size. Suburbs can be found in Guadalajara, Mexico City, Monterrey, and most major cities. Lomas de Chapultepec is an example of an affluent suburb, although it is located inside the city and by no means is today a suburb in the strict sense of the word. In other countries, the situation is similar to that of Mexico, with many suburbs being built, most notably in Peru and Chile, which have experienced a boom in the construction of suburbs since the late 1970s and early 1980s. As the growth of middle-class and upper-class suburbs increased, low-class squatter areas have increased, most notably "lost cities" in Mexico, campamentos in Chile, barriadas in Peru, villa miserias in Argentina, asentamientos in Guatemala and favelas of Brazil.

Brazilian affluent suburbs are generally denser, more vertical and mixed in use inner suburbs. They concentrate infrastructure, investment and attention from the municipal seat and the best offer of mass transit. True sprawling towards neighboring municipalities is typically empoverished – periferia (the periphery, in the sense of it dealing with spatial marginalization) –, with a very noticeable example being the rail suburbs of Rio de Janeiro – the North Zone, the Baixada Fluminense, the part of the West Zone associated with SuperVia's Ramal de Santa Cruz. These, in comparison with the inner suburbs, often prove to be remote, violent food deserts with inadequate sewer structure coverage, saturated mass transit, more precarious running water, electricity and communication services, and lack of urban planning and landscaping, while also not necessarily qualifying as actual favelas or slums. They often are former agricultural land or wild areas settled through squatting; suburbs grew and expanded due to the mass rural exodus during the years of the military dictatorship. This is particularly true of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Brasília, which grew with migration from more distant and impoverished parts of the country and deal with overpopulation as a result.

Malaysia

[edit]In Malaysia, suburbs are common especially in Klang Valley, the largest conurbation in the country.[56] These suburbs also serve as major housing areas and commuter towns. Terraced houses, semi-detached houses and shophouses are common concepts in suburban planning. In certain places such as Klang, Subang Jaya and Petaling Jaya, suburbs form the core. The latter one has been turned into a satellite city of Kuala Lumpur. Suburbs are also evident in other major conurbations in the country such as Penang Island (Butterworth, Bukit Mertajam), Johor Bahru (Skudai, Pasir Gudang), Ipoh (Simpang Pulai), Kota Melaka (Ayer Keroh), Kuching (Petra Jaya) and Alor Setar (Anak Bukit).

Russia

[edit]In Russia, until recently, the term suburb refers to high-rise residential apartments which usually consist of two bedrooms, one bathroom, a kitchen and a living room. However, since the beginning of the 21st century in Russia there has been a "cottage boom", as a result of which a huge number of cottage villages appeared in almost every city of the country (including Moscow), no different from the suburbs in western countries.[citation needed]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom suburbs are located between the exurbs and inner cities of a metropolitan area. The growth in the use of trains, and later cars and highways, increased the ease with which workers could have a job in the city while commuting in from the suburbs. In the United Kingdom, as mentioned above, railways stimulated the first mass exodus to the suburbs. The Metropolitan Railway, for example, was active in building and promoting its own housing estates in the north-west of London, consisting mostly of detached houses on large plots, which it then marketed as "Metro-land".[57] In the UK, the government is seeking to impose minimum densities on newly approved housing schemes in parts of South East England. The goal is to "build sustainable communities" rather than housing estates. However, commercial concerns tend to delay the opening of services until a large number of residents have occupied the new neighborhood.

United States

[edit]Many white people moved to the suburbs during the white flight.[58][59]

In the 19th century, horse-drawn and later electric trolleys enabled the creation of streetcar suburbs, which expanded the area in which city commuters could live. These are typically medium-density neighborhoods contiguous with the core urban area, built for pedestrian access to the streetcar lines.

With widespread adoption of the automobile progressing from the 1920s to the 1950s, and especially with the introduction of the Interstate Highway System, new suburbs were designed around car transport instead of pedestrians. Over time, many suburban areas, especially those not within the political boundaries of the city containing the central business area, began to see independence from the central city as an asset. In some cases, suburbanites saw self-government as a means to keep out people who could not afford the added suburban property maintenance costs not needed in city living. Federal subsidies for suburban development accelerated this process as did the practice of redlining by banks and other lending institutions.[60] In some cities such as Miami, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., the main city is much smaller than the surrounding suburban areas, leaving the city proper with a small portion of the metro area's population and land area.

Mesa, Arizona, and Virginia Beach, Virginia, the two most populous suburbs in the U.S., are actually more populous than many core cities, including Miami, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Cleveland, Tampa, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and others. Virginia Beach is now the most populous city in Virginia, having long since exceeded the population of its neighboring primary city, Norfolk. While Virginia Beach has slowly been taking on the characteristics of an urban city, it will not likely achieve the population density and urban characteristics of Norfolk. A second suburban city in Virginia, Chesapeake, has also exceeded the population of adjacent Norfolk. With only a few large commercial areas and no definitive downtown area, Chesapeake is primarily residential in nature with vast rural areas remaining within the city limits.

Cleveland, Ohio, is typical of many American central cities; its municipal borders have changed little since 1922, even though the Cleveland urbanized area has grown many times over.[citation needed] Several layers of suburban municipalities now surround cities like Boston, Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Dallas, Denver, Houston, New York City, San Francisco, Sacramento, Atlanta, Miami, Baltimore, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Phoenix, Norfolk, St. Louis, Salt Lake City, Las Vegas, Minneapolis, and Washington, D.C..

Suburbs in the United States have a prevalence of usually detached[61] single-family homes.[62]

They are characterized by:

- Lower densities than central cities, dominated by single-family homes on small plots of land – anywhere from 0.1 acres[12] and up – surrounded at close quarters by very similar dwellings.

- Zoning patterns that separate residential and commercial development, as well as different intensities and densities of development. Daily needs are not within walking distance of most homes.

- A greater percentage of whites (both non-Hispanic and, in some areas, Hispanic) and lesser percentage of citizens of other ethnic groups than in urban areas. However, black suburbanization grew between 1970 and 1980 by 2.6% as a result of central city neighborhoods expanding into older neighborhoods vacated by whites.[63][64][65]

- Subdivisions carved from previously rural land into multiple-home developments built by a single real estate company. These subdivisions are often segregated by minute differences in home value, creating entire communities where family incomes and demographics are almost completely homogeneous.[66]

- Shopping malls and strip malls behind large parking lots instead of a classic downtown shopping district.

- A road network designed to conform to a hierarchy, including culs-de-sac, leading to larger residential streets, in turn leading to large collector roads, in place of the grid pattern common to most central cities and pre-World War II suburbs.

- A greater percentage of one-story administrative buildings than in urban areas.

- Compared to rural areas, suburbs usually have greater population density, higher standards of living, more complex road systems, more franchised stores and restaurants, and less farmland and wildlife.

By 2010, suburbs increasingly gained people in racial minority groups, as many members of minority groups gained better access to education and sought more favorable living conditions compared to inner city areas.[original research?][opinion]

Conversely, many white Americans also moved back to city centers. Nearly all major city downtowns (such as Downtown Miami, Downtown Detroit, Downtown Philadelphia, Downtown Roanoke, or Downtown Los Angeles) are experiencing a renewal, with large population growth, residential apartment construction, and increased social, cultural, and infrastructural investments, as have suburban neighborhoods close to city centers. Better public transit, proximity to work and cultural attractions, and frustration with suburban life and gridlock have attracted young Americans to the city centers.[67]

The Hispanic and Asian population is increasing in the suburbs.[68]

Traffic flows

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Suburbs typically have longer travel times to work than traditional neighborhoods.[69] Only the traffic within the short streets themselves is less. This is due to three factors:[citation needed] almost-mandatory automobile ownership due to poor suburban bus systems and nearly-nonexistent rail systems, longer travel distances and the hierarchy system, which is less efficient at distributing traffic than the traditional grid of streets.

In the suburban system, most trips from one component to another component requires that cars enter a collector road[citation needed], no matter how short or long the distance is. This is compounded by the hierarchy of streets, where entire neighborhoods and subdivisions are dependent on one or two collector roads. Because all traffic is forced onto these roads, they are often heavy with traffic all day. If a traffic crash occurs on a collector road, or if road construction inhibits the flow, then the entire road system may be rendered useless until the blockage is cleared. The traditional "grown" grid, in turn, allows for a larger number of choices and alternate routes.

Suburban systems of the sprawl type are also quite inefficient for cyclists or pedestrians, as the direct route is usually not available for them either.[70] This encourages car trips even for distances as low as several hundreds of yards or meters (which may have become up to several miles or kilometers due to the road network). Improved sprawl systems, though retaining the car detours, possess cycle paths and footpaths connecting across the arms of the sprawl system, allowing a more direct route while still keeping the cars out of the residential and side streets.

More commonly, central cities seek ways to tax nonresidents working downtown – known as commuter taxes – as property tax bases dwindle. Taken together, these two groups of taxpayers represent a largely untapped source of potential revenue that cities may begin to target more aggressively, particularly if they're struggling. According to struggling cities, this will help bring in a substantial revenue for the city which is a great way to tax the people who make the most use of the highways and repairs.

Today more companies settle down in suburbs because of low property costs.

Criticism

[edit]Criticism of suburbia dates back to the boom of suburban development in the 1950s and critiques a culture of aspirational homeownership.[71] In the English-speaking world, this discourse is prominent in the United States and Australia being prevalent both in popular culture and academia.

In popular culture

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Suburbs and suburban living have been the subject for a wide variety of films, books, television shows and songs.

French songs like La Zone by Fréhel (1933), Aux quatre coins de la banlieue by Damia (1936), Ma banlieue by Reda Caire (1937), or Banlieue by Robert Lamoureux (1953), evoke the suburbs of Paris explicitly since the 1930s.[72] Those singers give a sunny festive, almost bucolic, image of the suburbs, yet still few urbanized. During the fifties and the sixties, French singer-songwriter Léo Ferré evokes in his songs popular and proletarian suburbs of Paris, to oppose them to the city, considered by comparison as a bourgeois and conservative place.

French cinema was although soon interested in urban changes in the suburbs, with such movies as Mon oncle by Jacques Tati (1958), L'Amour existe by Maurice Pialat (1961) or Two or Three Things I Know About Her by Jean-Luc Godard (1967).

In his one-act opera Trouble in Tahiti (1952), Leonard Bernstein skewers American suburbia, which produces misery instead of happiness.

The American photojournalist Bill Owens documented the culture of suburbia in the 1970s, most notably in his book Suburbia. The 1962 song "Little Boxes" by Malvina Reynolds lampoons the development of suburbia and its perceived bourgeois and conformist values,[73] while the 1982 song Subdivisions by the Canadian band Rush also discusses suburbia, as does Rockin' the Suburbs by Ben Folds. The 2010 album The Suburbs by the Canadian-based alternative band Arcade Fire dealt with aspects of growing up in suburbia, suggesting aimlessness, apathy and endless rushing are ingrained into the suburban culture and mentality. Suburb The Musical, was written by Robert S. Cohen and David Javerbaum. Over the Hedge is a syndicated comic strip written and drawn by Michael Fry and T. Lewis. It tells the story of a raccoon, turtle, a squirrel, and their friends who come to terms with their woodlands being taken over by suburbia, trying to survive the increasing flow of humanity and technology while becoming enticed by it at the same time. A film adaptation of Over the Hedge was produced in 2006.

British television series such as The Good Life, Butterflies and The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin have depicted suburbia as well-manicured but relentlessly boring, and its residents as either overly conforming or prone to going stir crazy. In contrast, U.S. shows such as Knots Landing, Desperate Housewives and Weeds portray the suburbs as concealing darker secrets behind a façade of manicured lawns, friendly people, and beautifully kept houses. Films such as The 'Burbs and Disturbia have brought this theme to the cinema.

Gallery

[edit]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Lands Clauses Consolidation Act 1845 (8 & 9 Vict. c. 18) required railways to sell off surplus lands within ten years of the time given for completion of the work in the line's enabling Act.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ Garreau, J., Edge City: Life on the New Frontier, Knopf Doubleday, 1992, p149

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 640. ISBN 9780415252256.

- ^ Jain, Shri V. K. (30 April 2021). Applied Ecology and Sustainable Environment. BFC Publications. ISBN 978-93-90880-19-5.

- ^ "A forgotten history of how the US Government Segregated America". NPR. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Hollow, Matthew (2011). "Suburban Ideals on England's Interwar Council Estates". Journal of the Garden History Society. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ The Fractured Metropolis: Improving the New City, Restoring the Old City, Reshaping the Region[permanent dead link] by Jonathan Barnett, via Google Books.

- ^ "suburb, n."

- ^ Psalter, British Library Add. MS. 17376, in Bülbring 1891, p. 188.

- ^ “The country lying immediately outside a town or city; more particularly, those residential parts belonging to a town or city that lie immediately outside and adjacent to its walls or boundaries” (Oxford English Dictionary 2011a; McManus and Ethington 2007, 319- 320).

- ^ Montgomery, David (7 July 2020). "How to Tell If You Live in the Suburbs". Bloomberg.com.

- ^ Brasuell, James (21 November 2018). "According to the Federal Government, the Suburbs Don't Exist". Planetizen.

- ^ a b Jackson 1985.

- ^ Ruth McManus, and Philip J. Ethington (2007). "Suburbs in transition: new approaches to suburban history". Urban History. 34 (2): 317–337. doi:10.1017/S096392680700466X. S2CID 146703204.

- ^ Adams, L. J. (1 September 2006). "Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism". Journal of American History. 93 (2): 601–602. doi:10.2307/4486372. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 4486372.

- ^ Mary Corbin Sies (2001). "North American Suburbs, 1880–1950". Journal of Urban History. 27 (3): 313–46. doi:10.1177/009614420102700304. S2CID 144947126.

- ^ "Luoyang and the Northern Army". Scholars of Shen Zhou.

- ^ a b "History of Suburbs". Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ Goodman, Robin; Buxton, Michael; Moloney, Susie (2016). "The early development of Melbourne". Planning Melbourne: Lessons for a Sustainable City. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9780643104747. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

By 1890, Melbourne was the second-largest city in the British Empire and one of the world's richest.

- ^

Gilbert, Alan (25 July 1989). "The Roots of Australian Anti-Suburbanism". In Goldberg, Samuels Louis; Smith, Francis Barrymore (eds.). Australian Cultural History (reprint ed.). Cambridge: CUP Archive (published 1988). p. 36. ISBN 9780521356510. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

[...] there has been surprising continuity since the infancy of Australian suburbia in the 1850s in the attitudes, values and motives underlying suburbanization.

- ^ Edwards, Dennis; Pigram, Ron (1988). The Golden Years of the Metropolitan Railway and the Metro-land Dream. Bloomsbury. p. 32. ISBN 1-870630-11-4.

- ^ Jackson 1986, p. 134.

- ^ Jackson 1986, pp. 134, 137.

- ^ a b Jackson 1986, p. 240.

- ^ a b Green 1987, p. 43.

- ^ Jackson 1986, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Rowley 2006, pp. 206, 207.

- ^ Green 2004, introduction.

- ^ "History of London Metro-Land and London's Suburbs". History.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 July 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Clapson, Mark (2000). "The suburban aspiration in England since 1919". Contemporary British History. 14: 151–174. doi:10.1080/13619460008581576. S2CID 143590157.

- ^ "The History of the Suburb". Hgstrust.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Outcomes of the War: Britain". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Lofthouse, Pamela (2012). "The Development of English Semi-detached Dwellings During the Nineteenth Century". Papers from the Institute of Archaeology. 22: 83–98. doi:10.5334/pia.404.

- ^ Ward David (1964). "A Comparative Historical Geography of Streetcar Suburbs in Boston, Massachusetts and Leeds, England: 1850–1920". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 54 (4): 477–489. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1964.tb01779.x.

- ^ Roger G. Panetta, Westchester: the American suburb (2006)

- ^ "The Postwar Economy: 1945–1960 < Postwar America < History 1994 < American History From Revolution To Reconstruction and beyond". Let.rug.nl. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Lizabeth (2003). A Consumer's Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. Vintage Books. pp. Chapter 6.

- ^ Muller, Peter O. (1977). "The Evolution of American Suburbs: A Geographical Interpretation". Urbanism Past & Present (4): 1–10. ISSN 0160-2780.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) series H-156

- ^ Joseph Goulden, The Best Years, 1945–1950 (1976) pp 135–39.

- ^ Barbara Mae Kelly, Expanding the American Dream: Building and Rebuilding Levittown (SUNY Press, 1993).

- ^ Rothstein, Richard: The Color of Law. A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Liveright, 2017.

- ^ Beauregard, Robert A. When America Became Suburban. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

- ^ "Zoning Requirements for Standard Lot in RS3 District". 47th Ward Public Service website. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Garden Cities of To-Morrow. Library.cornell.edu. Retrieved on 22 November 2011.

- ^ England, Robert E. and David R. Morgan. Managing Urban America, 1979.

- ^ "Eye of Africa". Eyeofafrica.co.za. 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "Eye of Africa". Eyeofafrica.co.za. 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "NSW Place and Road Naming Proposals System". proposals.gnb.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Dependence on cars in urban neighborhoods". Statistics Canada. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ The Wealthy Suburbs of Canada. Planetizen. Retrieved on 22 November 2011.

- ^ "CALGARY, AB an overview of development trends" (PDF). Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- ^ "THE CITY OF CALGARY Municipal Development Plan" (PDF). Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- ^ "(Mis)understanding China's Suburbs". China Urban Development Blog. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "Is This Beijing's Suburban Future?". The Atlantic. 10 February 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Nasser, Haya El. (18 April 2008) Modern suburbia not just in America anymore. Usatoday.com. Retrieved on 22 November 2011.

- ^ Aiken, S. Robert; Leigh, Colin H. (December 1975). "Malaysia's Emerging Conurbation". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 65 (4): 546–563. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1975.tb01062.x. JSTOR 2562422. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ London's metroland Archived 16 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Transportdiversions.com. Retrieved on 22 November 2011.

- ^ The Myth of the White Suburb and “Suburban Invasion”

- ^ Lamb, Charles M. (24 January 2005). Housing Segregation in Suburban America Since 1960: Presidential and Judicial Politics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-44418-7.

- ^ Comeback Cities: A Blueprint for Urban Neighborhood Revival By Paul S. Grogan, Tony Proscio. ISBN 0-8133-3952-9. Published 2002. Page 142. "Perhaps suburbanization was a 'natural' phenomenon—rising incomes allowing formerly huddled masses in city neighborhoods to breathe free on green lawn and leafy culs-de-sac. But, we will never know how natural it was, because of the massive federal subsidy that eased and accelerated it, in the form of tax, transportation and housing policies."

- ^ Land Development Calculations 2001 Walter Martin Hosack. "single-family detached housing" = "suburb houses" p133

- ^ "Housing Unit Characteristics by Type of Housing Unit, 2005" Energy Information Association

- ^ Barlow, Andrew L. (2003). Between fear and hope: globalization and race in the United States. Lanham, Maryland (Prince George's County): Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-1619-9.

- ^ Noguera, Pedro (2003). City schools and the American dream: reclaiming the promise of public education. New York: Teachers College Press. ISBN 0-8077-4381-X.

- ^ Naylor, Larry L. (1999). Problems and issues of diversity in the United States. Westport, Conn.: Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 0-89789-615-7.

- ^ Miller, Carissa Moffat; Blevins, Audie (1 March 2005). "Battlement Mesa: a case study of community evolution". The Social Science Journal. 42 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2004.11.001. ISSN 0362-3319. S2CID 143677128.

- ^ Yen, Hope. "White flight? Suburbs lose young whites to cities." Associated Press at Yahoo! News. Sunday 9 May 2010. Retrieved on 10 May 2010.

- ^ Minority Suburbanization

- ^ Kneebone; Holmes, Elizabeth; Natalie. "The growing distance between people and jobs in metropolitan America" (PDF). Bicycleuniverse.info.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FHWA Course on Bicycle and Pedestrian Transportation - Safety | Federal Highway Administration". safety.fhwa.dot.gov. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Boyd (1960).

- ^ "Chanson francaise La banlieue 1931–1953 Anthologie". Fremeaux.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Keil, Rob (2006). Little Boxes: The Architecture of a Classic Midcentury Suburb. Daly City, CA: Advection Media. ISBN 0-9779236-4-9.

Bibliography

[edit]- Archer, John; Paul J.P. Sandul, and Katherine Solomonson (eds.), Making Suburbia: New Histories of Everyday America. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

- Baxandall, Rosalyn and Elizabeth Ewen. Picture Windows: How the Suburbs Happened. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

- Beauregard, Robert A. When America Became Suburban. University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

- Boyd, Robin (1960). The Australian Ugliness. Melbourne: Penguin Books.

- The Earliest Complete English Prose Salter,ed. by K. D. Bülbring. Early English Text Society, Original Series, 1891.

- Fishman, Robert. Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia. Basic Books, 1987; in U.S.

- Foxell, Clive (1996). Chesham Shuttle: The Story of a Metropolitan Branch Line (2nd ed.). Clive Foxell. ISBN 0-9529184-0-4.

- Galinou, Mireille. Cottages and Villas: The Birth of the Garden Suburb (2011), in England

- Green, Oliver (1987). The London Underground: An illustrated history. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-1720-4.

- Green, Oliver, ed. (2004). Metro-Land (British Empire Exhibition 1924 reprinted ed.). Southbank Publishing. ISBN 1-904915-00-0. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- Harris, Richard. Creeping Conformity: How Canada Became Suburban, 1900–1960 (2004)

- Hayden, Dolores. Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820–2000. Vintage Books, 2003.

- Horne, Mike (2003). The Metropolitan Line. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-275-5.

- Jackson, Kenneth T. (1985). Crabgrass frontier: The suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504983-7. OCLC 11785435.

- Jackson, Alan (1986). London's Metropolitan Railway. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8839-8.

- Psalter, London, British Library Add. MS. 17376

- Rowley, Trevor (2006). The English landscape in the twentieth century. Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 1-85285-388-3.

- Simpson, Bill (2003). A History of the Metropolitan Railway. Volume 1: The Circle and Extended Lines to Rickmansworth. Lamplight Publications. ISBN 1-899246-07-X.

- Stilgoe, John R. Borderland: Origins of the American Suburb, 1820–1939. Yale University Press, 1989.

- Teaford, Jon C. The American Suburb: The Basics. Routledge, 2008.