Picul

| Picul | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 擔 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 担 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | đảm | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 담 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 擔 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 担 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | たん / ピクル, ㌯ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Malay name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Malay | pikul | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Indonesian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Indonesian | pikul | ||||||||||||||||||||||

A picul /ˈpɪkəl/,[1] dan[2] or tam,[3] is a traditional Asian unit of weight, defined as "as much as a man can carry on a shoulder-pole".[1] Historically, it was defined as equivalent to 100 or 120 catties, depending on time and region. The picul is most commonly used in southern China and Maritime Southeast Asia.

History

[edit]The unit originated in China during the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), where it was known as the shi (石 "stone"). During the Han dynasty, one stone was equal to 120 catties. Government officials were paid in grain, counted in stones, with top ranked ministers being paid 2000 stones.[4]

As a unit of measurement, the word shi (石) can also be pronounced dan. To avoid confusion, the character is sometimes changed to 擔 (dàn), meaning "burden" or "load". Likewise, in Cantonese the word is pronounced sek (石) or daam (擔), and in Hakka it is pronounced tam (擔).

The word picul appeared as early as the mid 9th century in Javanese. In modern Malay, pikul is also a verb meaning 'to carry on the shoulder'.

In the early days of Hong Kong as a British colony, the stone (石, with a Cantonese pronunciation given as shik) was used as a measurement of weight equal to 120 catties or 160 pounds (72.6 kg), alongside the picul of 100 catties.[5] It was made obsolete by subsequent overriding legislation in 1885, which included the picul but not the stone, to avoid confusion with European-origin measures that are similarly called stone.[6]

Following Spanish, Portuguese, British and most especially the Dutch colonial maritime trade, the term picul was both a convenient unit, and a lingua franca unit that was widely understood and employed by other Austronesians (in modern Malaysia and the Philippines) and their centuries-old trading relations with Indians, Chinese and Arabs. It remained a convenient reference unit for many commercial trade journals in the 19th century. One example is Hunts Merchant Magazine of 1859 giving detailed tables of expected prices of various commodities, such as coffee, e.g. one picul of Javanese coffee could be expected to be bought from 8 to 8.50 Spanish dollars in Batavia and Singapore.[7]

Definitions

[edit]

As for any traditional measurement unit, the exact definition of the picul varied historically and regionally. In imperial China and later, the unit was used for a measure equivalent to 100 catties.[8]

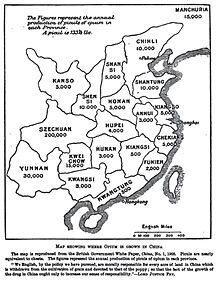

In 1831, the Dutch East Indies authorities acknowledged local variances in the definition of the pikul.[9] In Hong Kong, one picul was defined in Ordinance No. 22 of 1844 as 133+1⁄3 avoirdupois pounds.[5] The modern definition is exactly 60.478982 kilograms.[3] The measure was and remains used on occasion in Taiwan where it is defined as 60 kg.[10] The last, a measure of rice, was 20 picul, or 1,200 kg.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "picul". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "The Weights and Measures Act (1929)". Legislative Yuan. Archived from the original on 2014-04-25.

- ^ a b "Weights and Measures Ordinance". The Law of Hong Kong.

- ^ 《漢書》 百官公卿表

- ^ a b Weights and Measures – Ordinance No. 22 of 1844, Historical Laws of Hong Kong Online.

- ^ Weights and Measures Ordinance, 1885, Historical Laws of Hong Kong Online.

- ^ Freeman Hunt, Thomas Prentice Kettell, William Buck Dana. Hunt's merchants' magazine and commercial review, Volume 41.Freeman Hunt, 1859 Google PDF download: [1]

- ^ 新华字典 (Xīnhuá Zìdiǎn), Peking, 1984.

- ^ Abdul Rasyid Asba. Kopra Makassar: perebutan pusat dan daerah : kajian sejarah ekonomi politik regional di Indonesia. Yayasan Obor Indonesia, 2007. ISBN 978-979-461-634-5. 318 pages quoting Algemen Verslag Resdientie Banoemas 1831: ANRIJ and ANRIJ Makassar 291/18: Chinne Verslag van de Havenmeester

- ^ Weights and Measures in Use in Taiwan Archived 2010-12-29 at the Wayback Machine from the Republic of China Yearbook--Taiwan 2001.

- ^ Andrade, Tonio (2005). "Appendix A: Weights, Measures, and Exchange Rates". How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century. Columbia University Press.