Jammu and Kashmir (state)

| State of Jammu and Kashmir | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region formerly administered by India as a state | |||||||||||

| 1952–2019 | |||||||||||

Map of Jammu and Kashmir | |||||||||||

| Capital | Srinagar (May–October) Jammu (November–April)[1][clarification needed] | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| • Coordinates | 34°00′N 76°30′E / 34.0°N 76.5°E | ||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

• 1952–1965 as Sadr-e-Riyasat; 1965–1967 | Karan Singh (first) | ||||||||||

• 2018–2019[2] | Satya Pal Malik (last) | ||||||||||

| Chief Minister | |||||||||||

• 1952–1953 as Prime Minister | Sheikh Abdullah (first) | ||||||||||

• 2016–2018[3] | Mehbooba Mufti (last) | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Jammu and Kashmir Legislature | ||||||||||

• Upper house | Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Council (36 seats) | ||||||||||

• Lower house | Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly (89 seats) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Abolition of monarchy | 17 November 1952 | ||||||||||

| 14 May 1954 | |||||||||||

| 31 October 2019 | |||||||||||

| Political subdivisions | 22 districts | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Jammu[a] and Kashmir[b] was a region formerly administered by India as a state from 1952 to 2019, constituting the southern and southeastern portion of the larger Kashmir region, which has been the subject of a dispute between India, Pakistan and China since the mid-20th century.[5][6] The underlying region of this state were parts of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, whose western districts, now known as Azad Kashmir, and northern territories, now known as Gilgit-Baltistan, are administered by Pakistan. The Aksai Chin region in the east, bordering Tibet, has been under Chinese control since 1962.

After the Government of India repealed the special status accorded to Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 of the Indian constitution in 2019, the Parliament of India passed the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, which contained provisions that dissolved the state and reorganised it into two union territories – Jammu and Kashmir in the west and Ladakh in the east, with effect from 31 October 2019.[7] At the time of its dissolution, Jammu and Kashmir was the only state in India with a Muslim-majority population.

History

Establishment

After the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948, the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir was divided between India (which controlled the regions of Jammu, Kashmir Valley, and Ladakh) and Pakistan (which controlled Gilgit–Baltistan and Azad Kashmir).[8] Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession on 26 October 1947 after an invasion by Pakistani tribesmen. Sheikh Abdullah was appointed as the Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir as part of an interim government by Maharaja Hari Singh in March 1948.[9] In order to integrate the provisions of the instrument of accession relating to the powers of the state and Indian government, the Constituent Assembly of India drew up the draft provision named Article 306-A, which would later become Article 370.[10]

A constituent assembly for Jammu and Kashmir was convened to frame a new constitution for the state in October 1951, after an election in which all the seats were won by the Jammu & Kashmir National Conference party of Abdullah.[11]

Abdullah reached an agreement termed as the "Delhi Agreement" with Jawaharlal Nehru, the Prime Minister of India, on 24 July 1952. It extended provisions of the Constitution of India regarding citizenship and fundamental rights to the state, in addition to the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of India. Agreements were also reached on issues of abolishing the monarchy, as well as the state being allowed a separate flag and official language. The Delhi Agreement spelt out the relationship between the central government and the state through recognizing the autonomy of Jammu and Kashmir, while also declaring it as an integral part of India and granting the central government control of several subjects that were not a part of the instrument of accession.[12]

The government of Jammu and Kashmir quickly moved to adopt the provisions of the agreement.[13] The recommendations of the Drafting Committee on the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir regarding the monarchy were accepted by the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir on 21 August 1952. The Jammu and Kashmir Constitution Act 1939 was amended in November 1952 to adopt the resolutions and the monarchy was officially abolished on 12 November. The regent Karan Singh was formally elected as the Sadar-i-Riyasat or head of state by the Constituent Assembly and was later recognized by the President of India.[14] The amendments incorporating the provisions into the state constitution entered into force on 17 November.[15]

Integration with India

Abdullah however sought to make Article 370 permanent and began calling for the secession of the state from India, which led to his arrest in 1953.[16] Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad then became the Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir. The Constituent Assembly of the state passed a resolution in February 1954, extending some provisions of the Constitution of India and formally ratifying the accession of the state to India per the Instrument of Accession. A Presidential Order was passed on 14 May 1954 to implement the Delhi Agreement, drawing its validity from the resolution of the Constituent Assembly.[17][18]

The new Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir was adopted on 17 November 1956 and came into force on 26 January 1957.[19] Following this, the state constituent assembly dissolved itself and elections were held for the legislative assembly in 1957, with the National Conference winning 68 out of 75 seats.[20]

In 1956–57, China constructed a road through the disputed Aksai Chin area of Ladakh. India's belated discovery of this road culminated in the Sino-Indian War of 1962; China has since administered Aksai Chin.[8] Following the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, India and Pakistan signed the Simla Agreement, recognising a Line of Control in Kashmir, and committing to a peaceful resolution of the dispute through bilateral negotiations.[21]

In December 1964, the Indian government extended provisions of Articles 356 and 357 of the Constitution of India, which allowed for President's rule in the state.[22] In April 1965, the legislative assembly approved renaming the positions of Sadar-i-Riyasat to Governor and Wazir-i-Azam (Prime Minister) to Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir. Though the change had no actual effect on the legal structure of the state, it conveyed that the government of Jammu and Kashmir was equal to that of any other Indian state.[23]

Despite Nehru releasing the imprisoned Abdullah in April 1964 to initiate dialogue with Pakistan, it viewed these developments as leading to the inseparability of Jammu and Kashmir from India and launched an armed conflict,[22] infiltrating Kashmir during Operation Gibraltar in August 1965. However, it ultimately failed in its objective and both countries returned to the status quo after the Tashkent Declaration of 1966.[24] The government of Ghulam Mohammed Sadiq meanwhile rapidly extended many provisions of the Indian Constitution to further integrate the state into India.[25]

The failure of Pakistan in the 1971 Indo-Pakistani war weakened the Kashmiri nationalist movement and Abdullah dropped demands of secession. Under the Indira–Sheikh Accord of 1975, he recognised the region as a part of India, the state legislature requiring the approval of the President to make laws, and the Parliament of India being able to promulgate laws against secessionism. In return, Article 370 was left untouched and Abdullah became the Chief Minister of the state. The region remained mostly peaceful until his death in 1982.[26]

Kashmir insurgency

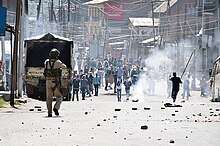

In the late 1980s, discontent over the high-handed policies of the union government and allegations of the rigging of the 1987 Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly election[27] triggered a violent uprising and armed insurgency[28][29] which was backed by Pakistan.[30] Pakistan claimed to be giving its "moral and diplomatic" support to the separatist movement.[31] The Inter-Services Intelligence of Pakistan has been accused by India and the international community of supporting, supplying arms and training mujahideen,[32][33] to fight in Jammu and Kashmir.[34][33][35] In 2015, former President of Pakistan Pervez Musharraf admitted that Pakistan had supported and trained insurgent groups in the 1990s.[36] India has repeatedly called Pakistan to end its "cross-border terrorism" in Kashmir.[31]

Since 1989, a prolonged, bloody conflict between the Islamic militant separatists and the Indian Army took place, both of whom have been accused of widespread human rights abuses, including abductions, massacres, rapes and armed robbery.[note 1] Several new militant groups with radical Islamic views emerged and changed the ideological emphasis of the movement to Islamic. This was facilitated by a large influx of Islamic "Jihadi" fighters (mujahadeen) who had entered the Kashmir valley following the end of the Soviet–Afghan War in the 1980s.[31]

By 1999, 94 out of the 97 subjects in the Union List and 260 out of 395 articles of the Constitution of India had become applicable in the state, though it retained some of its autonomy.[46] Article 370 had meanwhile become mostly symbolic.[10]

Following the 2008 Kashmir unrest, secessionist movements in the region were boosted.[47][48] The 2016–17 Kashmir unrest resulted in the death of over 90 civilians and the injury of over 15,000.[49][50] Six policemen, including a sub-inspector were killed in an ambush in Anantnag in June 2017, by trespassing militants of the Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Toiba.[51] An attack on an Indian police convoy in Pulwama, in February 2019, resulted in the deaths of 40 police officers. Responsibility for the attack was claimed by a Pakistan-backed militant group Jaish-e-Mohammed.[52]

Dissolution

In August 2019, both houses of the Parliament of India passed resolutions to amend Article 370 and extend the Constitution of India in its entirety to the state, which was implemented as a constitutional order by the President of India.[53][54] At the same time, the parliament also passed the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019, which contained provisions that dissolved the state of Jammu and Kashmir and established two new union territories: the eponymous union territory of Jammu and Kashmir, and that of Ladakh.[55]

The reorganisation act was assented to by the President of India, and came into effect on 31 October 2019.[56] Prior to these measures, the union government locked down the Kashmir Valley, increased security forces, imposed Section 144 that prevented assembly, and placed political leaders such as former Jammu and Kashmir chief ministers Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti under house arrest.[57] Internet and phone services were also blocked.[58][59][60]

Administrative divisions

The state of Jammu and Kashmir consisted of three divisions: the Jammu Division, the Kashmir Division and Ladakh which are further divided into 22 districts.[61] The Siachen Glacier, while under Indian military control, did not lie under the administration of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Kishtwar, Ramban, Reasi, Samba, Bandipora, Ganderbal, Kulgam and Shopian were districts formed in 2008.[61]

Districts

| Division | Name | Headquarters | Before 2007[62] | After 2007 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (km2) |

Area (km2) |

Area (sq miles) |

Rural Area (km2) |

Urban Area (km2) |

Source for area | |||

| Jammu | Kathua district | Kathua | 2,651 | 2,502 | 966 | 2,458.84 | 43.16 | [63] |

| Jammu district | Jammu | 3,097 | 2,342 | 904 | 2,089.87 | 252.13 | [64] | |

| Samba district | Samba | new district | 904 | 349 | 865.24 | 38.76 | [65] | |

| Udhampur district | Udhampur | 4,550 | 2,637 | 1,018 | 2,593.28 | 43.72 | [66] | |

| Reasi district | Reasi | new district | 1,719 | 664 | 1,679.99 | 39.01 | [67] | |

| Rajouri district | Rajouri | 2,630 | 2,630 | 1,015 | 2,608.11 | 21.89 | [68] | |

| Poonch district | Poonch | 1,674 | 1,674 | 646 | 1,649.92 | 24.08 | [69] | |

| Doda district | Doda | 11,691 | 8,912 | 3,441 | 8,892.25 | 19.75 | [70] | |

| Ramban district | Ramban | new district | 1,329 | 513 | 1,313.92 | 15.08 | [71] | |

| Kishtwar district | Kishtwar | new district | 1,644 | 635 | 1,643.37 | 0.63 | [72] | |

| Total for division | Jammu | 26,293 | 26,293 | 10,152 | 25,794.95 | 498.05 | calculated | |

| Kashmir | Anantnag district | Anantnag | 3,984 | 3,574 | 1,380 | 3,475.76 | 98.24 | [73] |

| Kulgam district | Kulgam | new district | 410 | 158 | 360.20 | 49.80 | [74] | |

| Pulwama district | Pulwama | 1,398 | 1,086 | 419 | 1,047.45 | 38.55 | [75] | |

| Shopian district | Shopian | new district | 312 | 120 | 306.56 | 5.44 | [76] | |

| Budgam district | Budgam | 1,371 | 1,361 | 525 | 1,311.95 | 49.05 | [77] | |

| Srinagar district | Srinagar | 2,228 | 1,979 | 764 | 1,684.42 | 294.53 | [78] | |

| Ganderbal district | Ganderbal | new district | 259 | 100 | 233.60 | 25.40 | [79] | |

| Bandipora district | Bandipora | new district | 345 | 133 | 295.37 | 49.63 | [80] | |

| Baramulla district | Baramulla | 4,588 | 4,243 | 1,638 | 4,179.44 | 63.56 | [81] | |

| Kupwara district | Kupwara | 2,379 | 2,379 | 919 | 2,331.66 | 47.34 | [82] | |

| Total for division | Srinagar | 15,948 | 15,948 | 6,158 | 15,226.41 | 721.54 | calculated | |

| Ladakh | Kargil district | Kargil | 14,036 | 14,036 | 5,419 | 14,033.86 | 2.14 | [83] |

| Leh district | Leh | 45,110 | 45,110 | 17,417 | 45,085.99 | 24.01 | [84] | |

| Total for division | Leh and Kargil | 59,146 | 59,146 | 22,836 | 59,119.85 | 26.15 | calculated | |

| Total | 101,387 | 101,387 | 39,146 | 100,141.21 | 1,245.74 | calculated | ||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1961 | 3,560,976 | — |

| 1971 | 4,616,632 | +29.6% |

| 1981 | 5,987,389 | +29.7% |

| 1991 | 7,837,051 | +30.9% |

| 2001 | 10,143,700 | +29.4% |

| 2011 | 12,541,302 | +23.6% |

| Source: Census of India[85] | ||

Jammu and Kashmir was the only state in India with a Muslim-majority population.[87] In the Census of India held in 1961, the first to be conducted after the formation of the state, Islam was practised by 68.31% of the population, while 28.45% followed Hinduism. The proportion of population that practised Islam fell to 64.19% by 1981 but recovered afterward.[88] According to the 2011 census, the last to be conducted in the state, Islam was practised by about 68.3% of the state population, while 28.4% followed Hinduism and small minorities followed Sikhism (1.9%), Buddhism (0.9%) and Christianity (0.3%).[89]

The state's official language was Urdu, which occupied a central space in media, education, religious and political discourses and the legislature of Jammu and Kashmir; the language functioned as a symbol of identity among Muslims of South Asia.[90] The first language of less than 1% of the population, it was regarded as a "neutral" and non-native language of the multilingual region, and broadly accepted by Kashmiri Muslims.[91][92] The dominant position of Urdu has been criticised for rendering Kashmiri into a functional "minority language", effectively restricting its use to households and family.[92][93]

The most widely spoken language is Kashmiri, the mother tongue of 53% of the population according to the 2011 census. Other major languages include Dogri (20%), Gojri (9.1%), Pahari (7.8%), Hindi (2.4%), Punjabi (1.8%),[86] Balti, Bateri, Bhadarwahi, Brokskat, Changthang, Ladakhi, Purik, Sheikhgal, Spiti Bhoti, and Zangskari. Additionally, several other languages, predominantly found in neighbouring regions, are also spoken by communities within Jammu and Kashmir: Bhattiyali, Chambeali, Churahi, Gaddi, Hindko, Lahul Lohar, Pangwali, Pattani, Sansi, and Shina.[94]

Government

Jammu and Kashmir was the only state in India which had special autonomy under Article 370 of the Constitution of India, according to which no law enacted by the Parliament of India, except for those in the field of defence, communication and foreign policy, would be extendable in Jammu and Kashmir unless it was ratified by the state legislature of Jammu and Kashmir.[95] The state was able to define the permanent residents of the state who alone had the privilege to vote in state elections, the right to seek government jobs and the ability to own land or property in the state.[96]

Jammu and Kashmir was the only Indian state to have its own official state flag, along with India's national flag,[97] in addition to a separate constitution. Designed by the then ruling National Conference, the flag of Jammu and Kashmir featured a plough on a red background symbolising labour; it replaced the Maharaja's state flag. The three stripes represented the three distinct administrative divisions of the state, namely Jammu, Valley of Kashmir, and Ladakh.[98]

Like all the states of India, Jammu and Kashmir had a multi-party democratic system of governance and had a bicameral legislature. At the time of drafting the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir, 100 seats were earmarked for direct elections from territorial constituencies. Of these, 25 seats were reserved for the areas of Jammu and Kashmir state that came under Pakistani control; this was reduced to 24 after the 12th amendment of the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir.[99] After a delimitation in 1988, the total number of seats increased to 111, of which 87 were within Indian-administered territory.[100] The Jammu and Kashmir Assembly had a 6-year term, in contrast to the norm of a 5-year term followed in every other state assemblies.[101][note 2] In 2005, it was reported that the Indian National Congress-led government in the state intended to amend the term to bring parity with the other states.[104]

Central provisions

In 1990, an Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act of India, which gave special powers to the Indian security forces, including the detaining of individuals for up to two years without presenting charges, was enforced in Jammu and Kashmir,[105][106] a decision which drew criticism from Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International for violating human rights.[107][108] Security forces claimed that many missing people were not detained, but had crossed into Pakistan-administered Kashmir to engage in militancy.[109]

Economy

The economy of Jammu and Kashmir was predominantly dependent on agriculture and related activities.[110] Horticulture played a vital role in the economic development of the state; produce included apples, apricots, cherries, pears, plums, almonds and walnuts.[111] The Doda district, rich in high-grade sapphire, had active mines until the 1989 insurgency; in 1998, the government discovered that smugglers had occupied these mines and stolen much of the resource.[112] Industrial development was constrained by the extreme mountainous landscape and power shortage.[113] Along with horticulture and agriculture, tourism is an important industry for Jammu and Kashmir, accounting for about 7% to its economy.[114]

Jammu and Kashmir was one of the largest recipients of grants from India; in 2004, this amounted to US$812 million.[115] Tourism, which was integral to the economy, witnessed a decline owing to the insurgency, but foreign tourism later rebounded, and in 2009, the state was one among the top tourist destinations in India.[116] The economy was also benefited by Hindu pilgrims who visited the shrines of Vaishno Devi and Amarnath Temple annually.[117] The British government had reiterated its advise against all travel to Jammu and Kashmir in 2013, with certain exceptions.[118]

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ The Hindu Net Desk (8 May 2017). "What is the Darbar Move in J&K all about?". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "Satya Pal Malik sworn in as Jammu and Kashmir governor". The Economic Times. Press Trust of India. 23 August 2018. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "BJP-PDP alliance ends in Jammu and Kashmir LIVE updates: Mehbooba Mufti resigns as chief minister; Governor's Rule in state". Firstpost. 19 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ a b Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8

- ^ Akhtar, Rais; Kirk, William, Jammu and Kashmir, State, India, Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved 7 August 2019 (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu and Kashmir, state of India, located in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent in the vicinity of the Karakoram and westernmost Himalayan mountain ranges. The state is part of the larger region of Kashmir, which has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since the partition of the subcontinent in 1947."

- ^ Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2003), Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: G to M, Taylor & Francis, pp. 1191–, ISBN 978-0-415-93922-5 Quote: "Jammu and Kashmir: Territory in northwestern India, subject to a dispute between India and Pakistan. It has borders with Pakistan and China."

- ^ "Jammu Kashmir Article 370: Govt revokes Article 370 from Jammu and Kashmir, bifurcates state into two Union Territories". The Times of India. PTI. 5 August 2019. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Kashmir – region, Indian subcontinent". Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ Jyoti Bhushan Daz Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer Publishing. p. 184. ISBN 9789401192316.

- ^ a b Waseem Ahmad Sofi (18 June 2021). Autonomy of a State in a Federation: A Special Case Study of Jammu and Kashmir. Springer Nature. pp. 79–81. ISBN 9789811610196.

- ^ Vipul Maheshwari; Anil Maheshwari (28 March 2022). The Power of the Ballot: Travail and Triumph in the Elections. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 124. ISBN 9789354353611.

- ^ Waseem Ahmad Sofi (17 June 2021). Autonomy of a State in a Federation: A Special Case Study of Jammu and Kashmir. Springer Publishing. pp. 91–93. ISBN 9789811610196.

- ^ Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta (6 December 2012). Jammu and Kashmir. Springer Publishing. p. 200. ISBN 9789401192316.

- ^ Waseem Ahmad Sofi (17 June 2021). Autonomy of a State in a Federation: A Special Case Study of Jammu and Kashmir. Springer Publishing. p. 94. ISBN 9789811610196.

- ^ Daya Sagar; Daya Ram (15 June 2020). Jammu & Kashmir: A Victim. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 222. ISBN 9788184303131.

- ^ Bibhu Prasad Routray (2012). Michelle Ann Miller (ed.). Autonomy and Armed Separatism in South and Southeast Asia. Chapter: Autonomy and Armed Separatism in Jammu and Kashmir. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 179. ISBN 9789814379977.

- ^ A. G. Noorani (5 December 2005). Constitutional Questions and Citizens' Rights: An Omnibus Comprising Constitutional Questions in India: The President, Parliament and the States and Citizens' Rights, Judges and State Accountability. Oxford University Press. p. 712. ISBN 978-0-19-908778-5.

- ^ Schofield 2003, p. 94

- ^ Fozia Nazir Lone (17 May 2018). Historical Title, Self-Determination and the Kashmir Question. Brill Publishers. p. 250. ISBN 9789004359994.

- ^ Sumantra Bose (2021). Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-Century Conflict. Yale University Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780300256871.

- ^ "Kashmir Fast Facts". CNN. 8 November 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ a b Hafeez Malik (27 July 2016). India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad: The Covert War in Kashmir, 1947-2004. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 184. ISBN 9781349105731.

- ^ Praveen Swami (19 October 2006). India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad: The Covert War in Kashmir, 1947-2004. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 9781134137527.

- ^ Matthew J. Webb (13 February 2012). Kashmir's Right to Secede: A Critical Examination of Contemporary Theories of Secession. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 9781136451454.

- ^ Waseem Ahmed Sofi (17 June 2021). Autonomy of a State in a Federation: A Special Case Study of Jammu and Kashmir. Springer Nature. p. 127. ISBN 9789811610196.

- ^ Kaushik Roy (2 March 2017). Scott Gates (ed.). Autonomy of a State in a Federation: A Special Case Study of Jammu and Kashmir. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 9781351877091.

- ^ Schofield 2003, p. 137

- ^ "1989 Insurgency". Kashmirlibrary.org. Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Contours of militancy". Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ Schofield 2003, p. 210

- ^ a b c "India Pakistan – Timeline". BBC News. BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ Ali, Mahmud (9 October 2006). "Pakistan's shadowy secret service". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ a b Rashid, Ahmed (6 October 2006). "Nato's top brass accuse Pakistan over Taliban aid". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ Gall, Carlotta (21 January 2007). "At Border, Signs of Pakistani Role in Taliban Surge". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Jehl, Douglas; Dugger, Celia W.; Barringer, Felicity (25 February 2002). "Death of Reporter Puts Focus On Pakistan Intelligence Unit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 May 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Pakistan supported, trained terror groups: Pervez Musharraf". Business Standard. Press Trust of India. 28 October 2015. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "India: "Everyone Lives in Fear": Patterns of Impunity in Jammu and Kashmir: I. Summary". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ "India and Human Rights in Kashmir – The Myth – India Together". Archived from the original on 9 May 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ Schofield 2003, pp. 148, 158

- ^ "India: "Everyone Lives in Fear": Patterns of Impunity in Jammu and Kashmir: VI. Militant Abuses". Archived from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ "Kashmir troops held after rape". BBC News. 19 April 2002. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ "219 Kashmiri Pandits killed by militants since 1989". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 24 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

The Jammu and Kashmir government on Tuesday said 219 Kashmiri Pandits were killed by militants since 1989 while 24,202 families were among the total 38,119 families which migrated out of the Valley due to turmoil

- ^ "Not myth, but the truth of migration". Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

The Pandits have preserved the threat letters sent to them. They have the audio and video evidence to show what happened. They have preserved the local newspapers through which they were warned to leave the Valley within 48 hours. This evidence also include still photographs of Pandits killed by militants and the desecrated temples.

- ^ "Pregnant woman in Doda accuses Lashkar militants of gang raping her repeatedly". The Indian News. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

A 31-year-old pregnant Gujjar woman has told police at the Baderwah Police Station in Jammu and Kashmir's Doda District that she was repeatedly gang raped by Lashkar-e-Toiba militants for two months.

- ^ "19/01/90: When Kashmiri Pandits fled Islamic terror". Rediff. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

Notices are pasted on doors of Pandit houses, peremptorily asking the occupants to leave Kashmir within 24 hours or face death and worse... In the preceding months, 300 Hindu men and women, nearly all of them Kashmiri Pandits, had been slaughtered following the brutal murder of Pandit Tika Lal Taploo, noted lawyer and BJP national executive member, by the JKLF in Srinagar on September 14, 1989. Soon after that, Justice N K Ganju of the Srinagar high court was shot dead. Pandit Sarwanand Premi, 80-year-old poet, and his son were kidnapped, tortured, their eyes gouged out, and hanged to death. A Kashmiri Pandit nurse working at the Soura Medical College Hospital in Srinagar was gang-raped and then beaten to death. Another woman was abducted, raped and sliced into bits and pieces at a sawmill.

- ^ Werner Menski; Muneeb Yousuf, eds. (17 June 2021). Kashmir After 2019: Completing the Partition. Springer Nature. p. 127. ISBN 9789811610196.

- ^ Avijit Ghosh (17 August 2008). "In Kashmir, there's azadi in air". Online edition of The Times of India, dated 17 August 2008. Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ^ Thottam, Jyoti (4 September 2008). "Valley of Tears". Time. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Yasir, Sameer (2 January 2017). "Kashmir unrest: What was the real death toll in the state in 2016?". Firstpost. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Akmali, Mukeet (23 January 2017). "After 15000 injuries, Govt to train forces in pellet guns". Greater Kashmir. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Express Web Desk (16 June 2017). "Six policemen, including sub-inspector, killed in militant ambush in Anantnag, Jammu and Kashmir". Online edition of The Indian Express, dated June 16, 2017. Archived from the original on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ Pulwama Attack 2019, everything about J&K terror attack on CRPF by terrorist Adil Ahmed Dar, Jaish-eMohammad Archived 18 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, India Today, 16 February 2019.

- ^ K. Venkataramanan (5 August 2019), "How the status of Jammu and Kashmir is being changed", The Hindu, archived from the original on 29 November 2019, retrieved 8 August 2019

- ^ "Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II, Section 3" (PDF). The Gazette of India. Government of India. 5 August 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Jammu & Kashmir Reorganisation Bill passed by Rajya Sabha: Key takeaways Archived 5 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Indian Express, 5 August 2019.

- ^ Ministry of Home Affairs (9 August 2019), "In exercise of the powers conferred by clause a of section 2 of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act." (PDF), The Gazette of India, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2019, retrieved 9 August 2019

- ^ Article 370 Jammu And Kashmir LIVE Updates: "Abuse Of Executive Power," Rahul Gandhi Tweets On Article 370 Removal Archived 6 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, NDTV, 6 August 2019.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Rebecca (6 August 2019). "Kashmir: Pakistan will 'go to any extent' to protect Kashmiris". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Inside Kashmir's lockdown: 'Even I will pick up a gun' Archived 13 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 10 August 2019.

- ^ "India revokes Kashmir's special status: All the latest updates". aljazeera. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Ministry of Home Affairs:: Department of Jammu & Kashmir Affairs". Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ "Divisions & Districts", Jamu & Kashmir Official Portal, 2012, archived from the original on 6 February 2021, retrieved 21 November 2020

- ^ District Census Handbook Kathua (PDF). Census of India 2011, Part A (Report). 18 June 2014. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ District Census Handbook Jammu, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 18 June 2014. pp. 13, 51, 116. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Jammu, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 13, 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020. - ^ District Census Handbook Samba, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 18 June 2014. pp. 9, 34, 36, 100. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Samba, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 10, 12, 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020. - ^ District Census Handbook Udhampur (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 12, 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ District Census Handbook Reasi, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 18 June 2014. pp. 9, 37, 88. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Reasi, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 9, 13, 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020. - ^ District Census Handbook Rajouri, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 18 June 2014. pp. 11, 107. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Rajouri, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 9, 10, 12, 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020. - ^ District Census Handbook Punch, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 18 June 2014. pp. 9, 99. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Punch, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 11, 13, 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020. - ^ District Census Handbook Doda, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 18 June 2014. pp. 9, 12, 99. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ District Census Handbook Ramban, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 18 June 2014. pp. 10, 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ District Census Handbook Kishtwar, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 18 June 2014. pp. 9, 10, 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

Part B page 9 says the rural area is 1643.65 km2, whilst pages 10 and 22 says 1643.37 km2. - ^ District Census Handbook Anantnag, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). July 2016. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Anantnag, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). July 2016. pp. 12, 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020. - ^ District Census Handbook Kulgam, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). July 2016. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Kulgam, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 12, 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

Part B page 12 says the area of the district is 404 km2, but page 22 says 410 km2. - ^ District Census Handbook Pulwama, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 12, 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ District Census Handbook Shupiyan, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Shupiyan, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 12, 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

Part B pages 12 and 22 say the district area is 312.00 km2, but Part A page 10 says 307.42 km2. - ^ District Census Handbook Badgam, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). July 2016. pp. 10, 46. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Badgam, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 11, 12, 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

Part A says the district area is 1371 km2, Part B says 1371 km2 (page 11) and 1361 km2 (page 12s and 22). - ^ District Census Handbook Srinagar, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). July 2016. pp. 11, 48. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

Part A page 48 says the district area was 2228.0 km2 in 2001 and 1978.95 km2 in 2011. - ^ District Census Handbook Ganderbal, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). July 2016. pp. 11, 12 and 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

Part B page 11 says the district area is 393.04 km2, but pages 12 and 22 say 259.00 km2. - ^ District Census Handbook Bandipora, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). July 2016. pp. 10, 47. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Bandipora, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 11, 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020. - ^ District Census Handbook Baramulla, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). July 2016. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Baramulla, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020. - ^ District Census Handbook Kupwara, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). July 2016. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Kupwara, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 11, 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020. - ^ District Census Handbook Kargil, Part A (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). July 2016. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

District Census Handbook Kargil, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. pp. 11, 12, 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020. - ^ District Census Handbook Leh, Part B (PDF). Census of India 2011 (Report). 16 June 2014. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "A-2 Decadal Variation In Population Since 1901". Censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ a b C-16 Population By Mother Tongue – Jammu & Kashmir (Report). Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Larson, Gerald James. "India's Agony Over Religion", 1995, page 245

- ^ "Share of Muslims and Hindus in J&K population same in 1961, 2011 Censuses". 29 December 2016. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ "C-1 Population By Religious Community". Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ Bhat, M. Ashraf (9 September 2011). Emergence of the Urdu Discourses in Kashmir (11 ed.). LANGUAGE IN INDIA.

- ^ Farouqi, Ather (2006). Redefining Urdu Politics in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Pandharipande, Rajeshwari (2002), "Minority Matters: Issues in Minority Languages in India" (PDF), International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 4 (2): 3–4, archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2016, retrieved 21 June 2016

- ^ Kachru, Braj B.; Kachru, Yamuna; Sridhar, S. N. (27 March 2008), Language in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, pp. 132–, ISBN 978-1-139-46550-2

- ^ Simons, Gary F; Fennig, Charles D, eds. (2018). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (21st ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- ^ "States: Jammu & Kashmir: Repeating History:By Harinder Baweja (3 July 2000)India Today". Archived from the original on 21 October 2007.

- ^ "Sorry". Indianexpress.com. Retrieved 18 July 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Under BJP pressure, J&K withdraws flag order". The Hindu. 14 March 2015. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ "The Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2012.

- ^ "Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir Section 4 Read with Section 48(a)". Kashmir-information.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ^ Luv Puri (24 October 2002). "The vacant seats". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

- ^ Rasheeda Bhagat (27 October 2005). "It is introspection time for Congress in J&K". The Hindu Businessline. Archived from the original on 6 January 2006. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

- ^ No need for constitutional amendment to bring J&K under 'one nation, one election': BJP Archived 20 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Greater Kashmir, 22 June 2019.

- ^ Meenakshi Lekhi, Why isn't Kashmir 'secular', Cong & NC must answer Archived 20 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Economic Times blog, 9 January 2014.

- ^ "Govt plans to reduce J&K Assembly's term to 5 years". The Tribune. 19 November 2005. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ^ The Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, 1990" Indian Ministry of Law and Justice Published by the Authority of New Deli

- ^ Huey, Caitlin (28 March 2011). "Amnesty International Cites Human Rights Abuse in Kashmir". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "India: Repeal Armed Forces Special Powers Act Archived 11 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- ^ "India: Accountability still missing for human rights violations in Jammu and Kashmir". Amnesty International. July 2015. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ "Kashmir graves: Human Rights Watch calls for inquiry". BBC News. 25 August 2011. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "CHAPTER III : Socio-Economic and Administrative Development" (PDF). Jammu & Kashmir Development Report. State Plan Division, Planning Commission, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ "CHAPTER IV : Potential Sectors of State Economy" (PDF). Jammu & Kashmir Development Report. State Plan Division, Planning Commission, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ Haroon Mirani (20 June 2008). "Sapphire-rich Kashmir". The Hindu Business Line. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ "Power shortage to hit India Inc". Rediff News. 2 April 2008. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ^ "Jammu and Kashmir's tourism flourishes, receives highest footfall since Independence". 7 October 2022.

- ^ Amy Waldman (18 October 2002). "Border Tension a Growth Industry for Kashmir". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ "Foreign tourists flock Kashmir". Online edition of The Hindu, dated 18 March 2009. Chennai, India. 18 March 2009. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ^ "Amarnath Board to study yatra impact on Kashmir economy". Online edition of The Hindu, dated 13 September 2007. Chennai, India. 13 September 2007. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ "India travel advice – GOV.UK". Fco.gov.uk. 9 April 2013. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

Sources

- Korbel, Josef (1953), "The Kashmir dispute after six years", International Organization, 7 (4): 498–510, doi:10.1017/S0020818300007256, ISSN 0020-8183, S2CID 155022750

- Korbel, Josef (1966) [first published 1954], Danger in Kashmir (second ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 9781400875238

- Schofield, Victoria (2003), Kashmir in Conflict, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-1-86064-898-4

- Snedden, Christopher (2003), Kashmir: The Untold Story, New Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers, ISBN 9780143030874

- Varshney, Ashutosh (1992), "Three Compromised Nationalisms: Why Kashmir has been a Problem" (PDF), in Raju G. C. Thomas (ed.), Perspectives on Kashmir: the roots of conflict in South Asia, Westview Press, pp. 191–234, ISBN 978-0-8133-8343-9

Further reading

- Bose, Sumantra (2003), Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01173-1

- Rai, Mridu (2004), Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir, C. Hurst & Co, ISBN 978-1850656616

- States and territories established in 1952

- States and territories disestablished in 2019

- Jammu and Kashmir (state)

- 1952 establishments in India

- 2019 disestablishments in India

- Disputed territories in Asia

- History of the Republic of India

- Territorial disputes of Pakistan

- Former states and territories of India