Don Daglow

Don Daglow | |

|---|---|

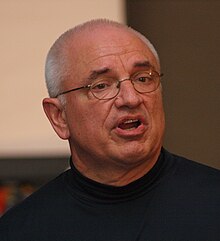

Don Daglow at the Game Developers Conference in 2010 | |

| Born | c. 1953 (age 70–71) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Game designer, programmer, producer |

| Website | https://www.daglowslaws.com/ |

Don Daglow (born circa 1953)[1] is an American video game designer, programmer, and producer. He is best known for being the creator of early games from several different genres, including pioneering simulation game Utopia for Intellivision in 1981, role-playing game Dungeon in 1975, sports games including the first interactive computer baseball game Baseball in 1971, and the first graphical MMORPG, Neverwinter Nights in 1991. He founded long-standing game developer Stormfront Studios in 1988.

In 2008 Daglow was honored at the 59th Annual Technology & Engineering Emmy Awards for Neverwinter Nights pioneering role in MMORPG development.[2] Along with John Carmack of id Software and Mike Morhaime of Blizzard Entertainment, Daglow is one of only three game developers to accept awards at both the Technology & Engineering Emmy Awards and at the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences Interactive Achievement Awards.[citation needed]

In 2003 he was the recipient of the CGE Achievement Award for "groundbreaking accomplishments that shaped the Video Game Industry."

University mainframe games in the 1970s

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

In 1971, Daglow was studying playwriting at Pomona College in Claremont, California. A computer terminal connected to the Claremont Colleges PDP-10 mainframe computer was set up in his dorm, and he saw this as a new form of writing. Like Kelton Flinn, another prolific game designer of the 1970s, his nine years of computer access as a student, grad student and grad school instructor throughout the 1970s gave him time to build a large body of major titles. Unlike Daglow and Flinn, most college students in the early 1970s lost all access to computers when they graduated, since home computers had not yet been invented.

Some of Daglow's titles were distributed to universities by the DECUS program-sharing organization, earning popularity in the free-play era of 1970s college gaming.

His best known games and experiments of this era include:

- Baseball (1971) — A member of Society for American Baseball Research,[3] Daglow created the first interactive computer baseball game,[4] allowing players to manage the game as it unfolded. It appeared ten years after John Burgeson wrote the first baseball simulation game, on an IBM 1620 at an IBM lab in Akron, Ohio. Daglow continued to expand Baseball throughout the 1970s, and ported the game to the Apple II in 1981, adding graphics in 1982. The simulation model in the Apple version in turn was ported to the Intellivision in 1982 as the basis for Intellivision World Series Baseball.

- Star Trek (1971) — One of several popular Star Trek computer games widely played in American colleges during this era, along with Mike Mayfield and Bob Leedom's Star Trek. Daglow's game was "the #2 Star Trek at most schools", garnering him fan mail after it was distributed through DECUS. The game printed out dialogue of characters on the Enterprise, describing the events of a battle with an enemy spaceship. The player could enter in choices, such as moving the Enterprise or firing phasers, and the game would advance accordingly until one of the ships surrendered, fled, or was destroyed.[5][6]

- Ecala (1973) — Improved version of the ELIZA computer conversation program. This project paved the way for his later work by suggesting new kinds of game interfaces.

- Dungeon (1975) — The first computer role playing game, based on the then-new Dungeons & Dragons gaming system. The game was steadily expanded over the following five years.

- Spanish Translator (1977) — As he experimented with parsers he created a context-sensitive Spanish translation program.

- Killer Shrews (1978) — A simulation game based on the cult sci-fi film The Killer Shrews. The player has not many decisions to make, only when to try to escape the island during the simulation of the depleting of the food that is there.

- Educational Dungeon (1979) — An attempt to make rote computer-aided instruction (CAI) programs more interesting by taking Dungeon and making correct answers propel the story.

Intellivision and Electronic Arts in the 1980s

[edit]In 1980, Daglow was hired as one of the original five in-house Intellivision programmers at Mattel during the first console wars.[7][8] Intellivision titles where he did programming and extensive ongoing design include:

- Geography Challenge (1981) — an educational title for the ill-fated Intellivision Keyboard component.

- Utopia — the first sim game or god game (1982). Utopia was a surprise hit and received wide press coverage for its unique design in an arcade-dominated era. The game has been named to two different video game halls of fame.

- Intellivision World Series Baseball (1983) — the first video game to use multiple camera angles to display the action rather than a static playfield; developed with Eddie Dombrower.

As the team grew into what in 1982 became known as the Blue Sky Rangers, Daglow was promoted to be Director of Intellivision Game Development, where he created the original designs for a number of Mattel titles in 1982-83 that were enhanced and expanded by other programmers, including:

- Tron: Deadly Discs (programmed by Steve Sents)

- Shark! Shark! (programmed by Ji-Wen Tsao)

- Buzz Bombers (programmed by Michael Breen)

- Pinball (programmed by Minh-Chau Tran).

During the Video Game Crash of 1983 Daglow was recruited to join Electronic Arts by founder Trip Hawkins, where he joined the EA producer team of Joe Ybarra and Stewart Bonn.

In addition to Dombrower, at EA, Daglow often worked with former members of the Intellivision team, including programmer Rick Koenig, artist Connie Goldman and musician Dave Warhol.

Daglow spent 1987–88 at Broderbund as head of the company's Entertainment and Education Division. Although he supervised the creation of games like Jordan Mechner's Prince of Persia, Star Wars, the Ancient Art of War series, and Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, his role was executive rather than creative. He took a lead role in signing the original distribution deal for SimCity with Maxis, and acquired the Star Wars license for Broderbund from Lucasfilm.

Stormfront Studios in the 1990s and 2000s

[edit]Looking to return to hands-on game development, Daglow founded game developer Stormfront Studios in 1988[7] in San Rafael, California.

By 1995 Stormfront had placed on the Inc. 500 list of fast-growing companies three times and Daglow stepped back from his design role to focus on the CEO position. See the article on Stormfront Studios for further information.

In 2003 and again in 2007 Daglow was elected to the board of directors of the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. He also serves on the San Francisco advisory board of the International Game Developers Association, the advisory board to the president of the Academy of Art University and served on the advisory board to the Games Convention Developers Conference until it was dissolved in 2008. In 2009, Daglow joined the board of GDC Europe.[9] He has been a keynote speaker, lecturer and panelist at game development conferences in Australia, Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Works

[edit]Games

[edit]Electronic Arts

[edit]- Realm of Impossibility (1984)

- Adventure Construction Set (1985)

- Racing Destruction Set (1985)

- Mail Order Monsters (1985)

- Thomas M. Disch's Amnesia (1986)

- Lords of Conquest (1986)

- World Tour Golf (1986)

- Super Boulder Dash (1986)

- Ultimate Wizard (1986)

- Earl Weaver Baseball (1987)[3] — again teamed with Eddie Dombrower. One of the earliest EA Sports titles, EWB was later named to the computer game Hall of Fame by Computer Gaming World and GameSpy. CGW named it as one of the top 25 games of all time in 1996.

- Patton Versus Rommel (1987)

- Return to Atlantis (1987)

1988–1995

[edit]Between 1988 and 1995 Daglow designed or co-designed the following titles:

- Tony La Russa Baseball (1991–1997) — with Michael Breen, Mark Buchignani, David Bunnett and Hudson Piehl, winner of multiple Game of the Year awards from Computer Gaming World and other publications.

- Quantum Space (1989–1991) — The first original play by email game offered by a major online service

- Gateway to the Savage Frontier (1991) — A Gold Box Dungeons & Dragons RPG for SSI, went to #1 on the U.S. game charts.

- Rebel Space (1992–1993) — with Mark Buchignani, David Bunnett and Hudson Piehl.

- Treasures of the Savage Frontier (1992) — Gold Box D&D RPG for SSI, the first game where an NPC could fall in love with a player character.

- Neverwinter Nights (1991–1997) — The first graphical MMORPG, with programmer Cathryn Mataga, and the top revenue producing title in the first ten years of online games. NWN paved the way for Ultima Online (1997), EverQuest (1999), and World of Warcraft (2004).

- Stronghold (1993) — The first 3D RTS game, with Mark Buchignani and David Bunnett

- Old Time Baseball (1995) — a baseball sim with over 12,000 players and 100 years of teams.

Fiction

[edit]During the late 1970s, Daglow worked as a teacher and graduate school instructor while pursuing his writing career. He was a winner of the National Endowment for the Humanities New Voices playwriting competition in 1975. His 1979 novelette The Blessing of La Llorona appeared in the April, 1982 issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction magazine.

Non-fiction

[edit]- Daglow, Don, The Changing Role of Computer Game Designers, Computer Gaming World, August, 1988, p. 18.

- Daglow, Don, The Dark Ages of Game Design, Computer Gaming World, May, 1986, p. 12.

- Daglow, Don, Through Hope-Colored Glasses: A Publisher's Perspective on Game Development, The Journal of Computer Game Design, 1(4) (1987), 3—5.

- DeMaria, Rusel & Wilson, Johnny L. (2003). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill/Osborne. ISBN 0-07-222428-2. Picture of Daglow Decles and Minkoff Measures Mattel softball teams, 1982

- Diesel, Vin (Foreword) (2004). Thirty Years of Adventure : A Celebration of Dungeons & Dragons. Wizards of the Coast. ISBN 0-7869-3498-0.

- Fullerton, Tracy; Swain, Christopher & Hoffman, Steven (2004). Game Design Workshop: Designing, Prototyping, and Playtesting Games. CMP Books. ISBN 1-57820-222-1.

- Krawczyk, Marianne & Novak, Jeannie (2006). Game Development Essentials: Game Story & Character Development. Thomson Delmar Learning. ISBN 1-4018-7885-7.

- Novak, Jeannie (2004). Game Development Essentials: An Introduction. Thomson Delmar Learning. ISBN 1-4018-6271-3.

References

[edit]- ^ "Don Daglow". Nodontdie.com. 11 August 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ "2008 Tech Emmy Winners". Kotaku.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012.

- ^ a b "Designing People..." Computer Gaming World. August 1992. pp. 48–54. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Game Design Workshop: Designing, Prototyping, & Playtesting Games - Tracy Fullerton, Chris Swain, Steven Hoffman - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved on 2014-05-22.

- ^ Wallis, Alistair (2006-10-19). "Column: 'Playing Catch Up: Stormfront Studios' Don Daglow'". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- ^ Maragos, Nich (2004-07-26). "Talking: Dan Daglow". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 2004-12-20. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- ^ a b Olsen, Jennifer (July 2001). "Profiles: Don Daglow—breaking typecasts", Game Developer 8 (7): 18.

- ^ Daglow, Don L. (August 1988). "The Changing Role of Computer Game Designers" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 50. p. 18. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "Game Developers Conference - 2009 GDC Europe Announces Advisory Board". Gdconf.com. 2009-04-08. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved 2014-05-22.