Boston, Lincolnshire

| Boston | |

|---|---|

| Market town | |

St Botolph's Church viewed from the river | |

Location within Lincolnshire | |

| Area | 18.42 km2 (7.11 sq mi) |

| Population | 45,339 (2021 Census.Ward)[1] |

| • Density | 2,461/km2 (6,370/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TF329437 |

| • London | 100 mi (160 km) S |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Areas of the town[2] (2021 census BUASD) | |

| Post town | BOSTON |

| Postcode district | PE21 |

| Dialling code | 01205 |

| Police | Lincolnshire |

| Fire | Lincolnshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Boston is a market town and inland port in the borough of the same name in the county of Lincolnshire, England.

Boston is the administrative centre of the wider Borough of Boston local government district. The town had a population of 45,339 at the 2021 census,[3] while the borough had an estimated population of 66,900 at the ONS mid-2015 estimates.[4]

Boston's most notable landmark is St Botolph's Church, colloquially referred to as 'The Stump', the largest parish church in England,[5] which is visible from miles away across the flat lands of Lincolnshire. Residents of Boston are known as Bostonians. Emigrants from Boston named several other settlements around the world after the town, most notably Boston, Massachusetts, then a colony and now part of the United States.

Toponymy

[edit]

The name Boston is said to be a contraction of "Saint Botolph's town",[6] "stone" or "tun" (Old English, Old Norse and modern Norwegian for a hamlet or farm; hence the Latin villa Sancti Botulfi "St. Botulf's village").[7] The name Botulfeston appears in 1460, with an alias "Boston".[8]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The town was once said to have been a Roman settlement, but no evidence shows this to be the case.[6] Similarly, it is often linked to the monastery established by the Saxon monk Botolph at "Icanhoe" on the Witham in AD 654 and destroyed by the Vikings in 870,[6] but this is doubted by modern historians. The early medieval geography of The Fens was much more fluid than it is today, and at that time, the Witham did not flow near the site of Boston. Botolph's establishment is most likely to have been in Suffolk. However, he was a popular missionary and saint to whom many churches between Yorkshire and Sussex are dedicated.[citation needed]

The 1086 Domesday Book does not mention Boston by name,[9] but nearby settlements of the tenant-in-chief Count Alan Rufus of Brittany are covered. Its present territory was probably then part of the grant of Skirbeck,[9] part of the very wealthy manor of Drayton, which before 1066 had been owned by Ralph the Staller, Edward the Confessor's Earl of East Anglia. Skirbeck had two churches and one is likely to have been that dedicated to St Botolph, in what was consequently Botolph's town. Skirbeck (map) is now considered part of Boston, but the name remains, as a church parish and an electoral ward.

The order of importance was the other way round, when the Boston quarter of Skirbeck developed at the head of the Haven, which lies under the present Market Place. At that stage, The Haven was the tidal part of the stream, now represented by the Stone Bridge Drain (map), which carried the water from the East and West Fens. The line of the road through Wide Bargate, to A52 and A16, is likely to have developed on its marine silt levees.[citation needed] It led, as it does now, to the relatively high ground at Sibsey (map), and thence to Lindsey.

The reason for the original development of the town, away from the centre of Skirbeck, was that Boston lay on the point where navigable tidal water was alongside the land route, which used the Devensian terminal moraine ridge at Sibsey, between the upland of East Lindsey and the three routes to the south of Boston:

- The coastal route, on the marine silts, crossed the mouth of Bicker Haven towards Spalding.

- The Sleaford route, into Kesteven, passed via Swineshead (map), thence following the old course of the River Slea, on its marine silt levee.

- The Salters' Way route into Kesteven, left Holland from Donington. This route was much more thoroughly developed, in the later Medieval period, by Bridge End Priory (map).

The River Witham seems to have joined The Haven after the flood of September 1014, having abandoned the port of Drayton, on what subsequently became known as Bicker Haven.[citation needed] The predecessor of Ralph the Staller owned most of both Skirbeck and Drayton, so it was a relatively simple task to transfer his business from Drayton, but Domesday Book in 1086 still records his source of income in Boston under the heading of Drayton, so Boston's name is not mentioned. The Town Bridge still maintains the preflood route, along the old Haven bank.

Growth

[edit]After the Norman conquest, Ralph the Staller's property was taken over by Count Alan.[10] It subsequently came to be attached to the Earldom of Richmond, North Yorkshire, and known as the Richmond Fee. It lay on the left bank of The Haven.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, Boston grew into a notable town and port.[11] In 1204, King John vested sole control over the town in his bailiff.[9] That year[6] or the next,[9] he levied a "fifteenth" tax (quinzieme) of 6.67% on the moveable goods of merchants in the ports of England: the merchants of Boston paid £780, the highest in the kingdom after London's £836.[6][12] Thus, by the opening of the 13th century, Boston was already significant in trade with the continent of Europe and ranked as a port of the Hanseatic League.[13][14] In the thirteenth century it was said to be the second port in the country.[15] Edward III named it a staple port for the wool trade in 1369.[9] Apart from wool, Boston also exported salt, produced locally on the Holland coast, grain, produced up-river, and lead, produced in Derbyshire and brought via Lincoln, up-river.

A quarrel between the local and foreign merchants led to the withdrawal of the Hansards[6] around 1470.[9] Around the same time, the decline of the local guilds[9] and shift towards domestic weaving of English wool (conducted in other areas of the country)[citation needed] led to a near-complete collapse of the town's foreign trade.[9] The silting of the Haven only furthered the town's decline.

At the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII during the English Reformation, Boston's Dominican, Franciscan, Carmelite, and Augustinian friaries—erected during the boom years of the 13th and 14th centuries—were all expropriated. The refectory of the Dominican friary was eventually converted into a theatre in 1965 and now houses the Blackfriars Arts Centre.

Henry VIII granted the town its charter in 1545[16] and Boston had two Members of Parliament from 1552.

17th and 18th centuries

[edit]

The staple trade made Boston a centre of intellectual influence from the Continent, including the teachings of John Calvin that became known as Calvinism. This, in turn, revolutionised the Christian beliefs and practices of many Bostonians and residents of the neighbouring shires of England. In 1607, a group of pilgrims from Nottinghamshire led by William Brewster and William Bradford attempted to escape pressure to conform with the teaching of the English church by going to the Netherlands from Boston. At that time, unsanctioned emigration was illegal, and they were brought before the court in the Guildhall. Most of the pilgrims were released fairly soon, and the following year, set sail for the Netherlands, settling in Leiden. In 1620, several of these were among the group who moved to New England in the Mayflower.[citation needed]

Boston remained a hotbed of religious dissent. In 1612, John Cotton became the Vicar of St Botolph's [17] and, although viewed askance by the Church of England for his nonconformist preaching, became responsible for a large increase in Church attendance. He encouraged those who disliked the lack of religious freedom in England to join the Massachusetts Bay Company, and later helped to found the city of Boston, Massachusetts, which he was instrumental in naming. Unable to tolerate the religious situation any longer, he eventually emigrated himself in 1633. [17]

At the same time, work on draining the fens to the west of Boston was begun, a scheme which displeased many whose livelihoods were at risk. (One of the sources of livelihood obtained from the fen was fowling, supplying ducks and geese for meat and in addition the processing of their feathers and down for use in mattresses and pillows. Until 2018, the feathery aspect of this was still reflected in the presence of the local bedding company named Fogarty.[18]) This and the religious friction put Boston into the parliamentarian camp in the Civil War, which in England began in 1642. The chief backer of the drainage locally, Lord Lindsey, was shot in the first battle and the fens returned to their accustomed dampness until after 1750.[citation needed]

The later 18th century saw a revival when the Fens began to be effectively drained. The Act of Parliament permitting the embanking and straightening of the fenland Witham was dated 1762. A sluice, called for in the act, was designed to help scour out The Haven. The land proved to be fertile, and Boston began exporting cereals to London. In 1774, the first financial bank was opened, and in 1776, an act of Parliament allowed watchmen to begin patrolling the streets at night.[citation needed]

Modern history

[edit]In the 19th century, the names of Howden, a firm located near the Grand Sluice, and Tuxford, near the Maud Foster Sluice, were respected among engineers for their steam road locomotives, threshing engines, and the like. Howden developed his business from making steam engines for river boats, while Tuxford began as a miller and millwright. His mill was once prominent near Skirbeck Church, just to the east of the Maud Foster Drain.[citation needed]

The railway reached the town in 1848, and it was briefly on the main line from London to the north. The area between the Black Sluice and the railway station was mainly railway yard and the railway company's main depot. The latter facility moved to Doncaster when the modern main line was opened. Boston remained something of a local railway hub well into the 20th century, moving the produce of the district and the trade of the dock, plus the excursion trade to Skegness.

Boston once again became a significant port in trade and fishing in 1884, when the new dock with its associated wharves on The Haven were constructed. It continued as a working port, exporting grain, fertiliser, and importing timber, although much of the fishing trade was moved out in the interwar period.[citation needed]

At the beginning of the First World War, a number of the town's trawlermen, together with some from Grimsby, were taken prisoner after their ships were sunk by German raiders in the North Sea. Their families did not know what had happened to them until late September 1914. The men were taken to Sennelager camp, then on to Ruhleben POW camp, where most remained until repatriated in 1918. A full report of their homecoming is in the Lincolnshire Standard newspaper, January 1918. During the war the port was used by hospital ships and some 4,000 sick or wounded troops passed through Boston.[19] The town was bombed by a Zeppelin on 2 September 1916, injuring three adults and killing a child.[20]

The first cinema opened in 1910, and in 1913, a new town bridge was constructed. Central Park was purchased in 1919, and is now one of the focal points of the town. Electricity came to Boston during the early part of the century, and electrical street lighting was provided from 1924.[21]

During the Second World War, 17 residents of the borough were killed by enemy air raids.[22] A memorial in Boston Cemetery commemorates them.[19]

The Haven Bridge, which now carries the two trunk roads over the river, was opened in 1966, and a new dual carriageway, John Adams Way, was built in 1976–8 to take traffic away from the town centre. A shopping centre, named the Pescod Centre, opened in 2004, bringing many new shops into the town.

Healthcare

[edit]Boston Cottage Hospital opened in 1871,[23] was rebuilt in the 1960s,[24] and is now called the Pilgrim Hospital, having been officially opened by Princess Anne on 23 June 1977.[25] The hospital is currently building a new Emergency Department extension next to the current one, costing £35 million and doubling the current department in size.[citation needed]

Transport

[edit]Railway

[edit]Boston railway station is a stop on the Poacher Line; East Midlands Railway operates a generally hourly service between Nottingham, Grantham and Skegness.[26] These services are run by the Class 170, 158 or the older Class 156 trains.[citation needed]

The railways came to Boston in 1848, following the building of the East Lincolnshire Railway from Grimsby to Boston and the simultaneous building of the Lincolnshire Loop Line by the Great Northern Railway, which ran between Peterborough and York, via Boston, Lincoln and Doncaster. This line was built before the East Coast Main Line and, for a short while, put Boston on the map as the GNR's main locomotive works before it was relocated to Doncaster in 1852.[citation needed]

Boston was the southern terminus of the East Lincolnshire Line to Louth and Grimsby, until its closure in 1970.[citation needed]

Buses

[edit]Bus services in the area are operated predominantly by Stagecoach East, Stagecoach East Midlands and Brylaine Travel. Key routes link the town with Lincoln, Skegness and Spalding.[27]

Politics

[edit]

Boston residents voted strongly (75.6%) in favour of leaving the European Union in the 2016 UK referendum on EU membership, the highest such vote in the country.[28]

Boston Borough Council

[edit]In the 2019 Borough elections, the Conservatives were confirmed as the majority party on Boston Borough Council with 16 of the 30 seats, followed by independents with 11.[29]

In May 2007, a single-issue political party, the Boston Bypass Independents campaigning for a bypass to be built around the town, took control of the council when they won 25 of the 32 council seats,[30] losing all but four of them in the subsequent election in 2011.

Governance

[edit]Boston received its charter in 1546.[31] It is the main settlement in the Boston local government district of Lincolnshire, which includes the unparished town of Boston and 18 other civil parishes.[32] The borough council is based in the Municipal Buildings in West Street.[33]

Borough Council wards

[edit]As of 2015, Boston Borough council consisted of 30 members:[34]

- Coastal Ward elects two councillors

- Fenside Ward elects two councillors.

- Fishtoft Ward elects three councillors.

- Five Villages Ward elects two councillors.

- Kirton & Frampton Ward elects three councillors.

- Old Leake & Wrangle elects two councillors

- Skirbeck Ward elects three councillors.

- Staniland Ward elects two councillors.

- Station Ward elects one councillor.

- St Thomas Ward elects one councillor.

- Swineshead & Holland Ward elects two councillors.

- Trinity Ward elects two councillors.

- West Ward elects one councillor.

- Witham Ward elects two councillors.

- Wyberton Ward elects two councillors.

Lincolnshire County Council divisions

[edit]In 2017, six county council divisions existed for the Borough of Boston, each of which returned one member to Lincolnshire County Council:

- Boston Coastal

- Boston North

- Boston Rural

- Boston South

- Boston West

- Skirbeck

UK Parliament

[edit]The town is part of the Boston and Skegness parliamentary constituency, currently represented by Reform UK chairman, Richard Tice.

Demography

[edit]According to the 2021 Census, the population of Boston is around 70,500. This is 9.1% higher than the 64,600 reported in the 2011 Census. This was a higher percentage of growth than the 6.6% national average for England during the same period.[5] Much of this population growth is due to high levels of immigration to the town, especially from eastern Europe. The 2021 Census states that 23.6% of Boston's population was born outside of the UK. 5.6% of the population of Boston was born in Lithuania and 5.4% was born in Poland. This is the highest proportion of Lithuanians anywhere in the UK and the second highest number of Poles, behind Slough, Berkshire.[14] Polish is the main language of 5.68% of the inhabitants.

Arts and culture

[edit]Boston has historically had strong cultural connections to the Netherlands, and Dutch influence can be found in its architecture.[35]

Landmarks

[edit]

The parish church of Saint Botolph is known locally as Boston Stump and is renowned for its size and its dominant appearance in the surrounding countryside.

The Great Sluice is disguised by railway and road bridges, but it is there, keeping the tide out of the Fens and twice a day, allowing the water from the upland to scour the Haven. Not far away, in the opposite direction, was the boyhood home of John Foxe, the author of Foxe's Book of Martyrs.[36]

The Town Bridge maintains the line of the road to Lindsey and from its western end, looking at the river side of the Exchange Building to the right, it is possible to see how the two ends of the building, founded on the natural levees of The Haven, have stood firm while the middle has sunk into the infill of the former river.[citation needed]

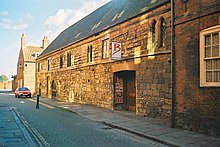

From 1552, Bostonians used to have their jail near the Stump (about where the red car in the photograph is located). This is likely to be where the Scrooby Pilgrims were imprisoned in 1607.

There is a statue of Herbert Ingram, founder of The Illustrated London News, in front of the Stump. The statue was designed by Alexander Munro and was unveiled in October 1862. The allegorical figure at the base of the monument is a reference to Ingram's efforts to bring the first piped water to the town. He was also instrumental in bringing the railways to Boston. Born in nearby Paddock Grove, son of a butcher,[37] he was also MP for Boston, from 1856 until his death in 1860, in a shipping accident on Lake Michigan.[38]

The seven-storeyed Maud Foster Tower Windmill, completed in 1819 by millwrights Norman and Smithson of Kingston upon Hull for Issac and Thomas Reckitt, was extensively restored in the late 1980s and became a working mill again. It stands next to the drain after which it is named, and is unusual in having an odd number (five) of sails.

The Guildhall in which the Pilgrim Fathers were tried was converted into a museum in 1929. The cells in which the pilgrims are said to have been held at the time of their trial are on the ground floor. After a major refurbishment during which the museum was closed for several years, it reopened in 2008.

The Pilgrim Fathers Memorial is located on the north bank of The Haven a few miles outside the town. Here at Scotia Creek, the pilgrims made their first attempt to leave for the Dutch Republic in 1607.[citation needed]

The ruined Hussey Tower is all that remains of a medieval brick-fortified house, built in 1450, and occupied by John Hussey, 1st Baron Hussey of Sleaford until he was executed in the wake of the Lincolnshire Rising.[39] 2 miles (3 km) east, Rochford Tower is another medieval tower house.[40]

In Skirbeck Quarter, on the right bank of The Haven, is the Black Sluice, the outfall of the South Forty-Foot Drain.[citation needed]

The Prime Meridian passes through the eastern side of Boston, marked by the fairly modern, suburban Meridian Road (PE21 0NB), which straddles the line after which the road was named.[41]

The annual Boston May Fair has been held in the town since at least 1125. This fair is held during the first week of May, and is one of the few remaining fairs in the country still held in the town centre. By tradition, the fair was officially opened by the mayor at midday on 3 May, although this date has varied in recent years.

The Haven Gallery, opened in 2005, was closed to the public in 2010 in a cost-cutting measure by Boston Borough Council.[42]

Blackfriars is a theatre and arts centre[43] that was formerly the refectory of the Benedictine friary, built in the 13th century and once visited by King Edward I.

Frampton Marsh and Freiston Shore are two nature reserves, managed by the RSPB, which lie on The Wash coast on either side of the mouth of The Haven.[44][45]

The Boston Preservation Trust has recently extended its Blue Plaque Trail to include a total of 27 examples (as of 2024) of significant heritage to the town and its place in the world. The 2024 additions include:

- Lindum House, the former home of Sir George Gilbert Scott[46]

- Scott House (Boston Workhouse entrance building), designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott[47]

- The Arbor Club[48]

- The Warehouse, former home and workshops of Mary Farmer and Terry Moores[49] Plaque #68778 on Open Plaques

Local economy

[edit]Boston's most important industries are food production, including vegetables and potatoes; road haulage and logistics companies that carry the food; the Port of Boston, which handles more than one million tons of cargo per year including the import of steel and timber and the export of grain and recyclable materials; shellfishing; other light industry; and tourism. The port is connected by rail, with steel imports going by rail each day to Washwood Heath in Birmingham, and the port and town are also connected by trunk roads including the A16 and the A52.

Boston's market[50] is held every Wednesday and Saturday[51] in one of England's largest marketplaces, with an additional market and outside auction held on Wednesdays on Bargate Green.

The Town has many local and national stores. Pescod Square shopping centre, located in the centre of town, houses several branded stores including Next, HMV, Waterstones and Wilko. Other big name stores in Boston include New look, Sports direct, Dunelm, TKMAXX and boots. There are several supermarkets, a Tesco and Asda, an Aldi and 2 Lidls. Several Lincolnshire coops are located around the town and both Sainsburys (inside Dobbies Garden Center) and Morrisons (in the town center) have a small presence. In 2021 a new department store opened in the Town centre called Rebos, filling the hole Oldrids and Downtown left when they vacated their Bargate department store in 2020, after 216 years of service, and moved to a new site on the outskirts of town.[citation needed]

In late 2013, a £100 million development was announced for the outskirts of town on the A16 towards Kirton. This development, named the Quadrant, is split in two phases. Phase one consists of a new football ground for Boston United F.C., 500 new homes, retail and business outlets, and a possible supermarket. This development also includes the beginning of a distributor road that will eventually link the A52 Grantham Road and the A16 together. Phase two, still in the development stage, consists of a possible second new marina, more new homes, and retail units.

Crime

[edit]In 2016, Boston was named as the most murderous place in England and Wales.[52][53][54]

Health

[edit]In the mid-2000s Boston was shown to have the highest obesity rate of any town in the United Kingdom, with one-third of its adults (31%) considered clinically obese. Obesity has been linked to social deprivation.[55]

Sport

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2023) |

Rugby

[edit]The Princess Royal Arena is located on the Boardsides, just outside Boston, and is the home of Boston Rugby Football Club. The club was established in 1927 by Ernst Clark, who had an interest in providing activity for boys.

Football

[edit]The town has two nonleague football clubs. The more senior Boston United, nicknamed the Pilgrims, plays in the National League following promotion in 2024. The stadium is currently located on York Street in the centre of the town and has an approximate capacity of 6,200. Boston United moved out of their former ground, York Street, for the 2020–21 season, to the Jakeman's stadium on the outskirts of town.[56] The town's second club, Boston Town, nicknamed the Poachers, plays in the United Counties Football League. Its home games are played at their stadium on Tattershall Road, on the outskirts of Boston.

Rowing

[edit]Boston Rowing Club, near Carlton Road, hosts the annual 33 miles (53 km) Boston Rowing Marathon each year in mid-September. Crews from throughout the world compete, starting at Brayford Pool in Lincoln, and finishing in times from three to six hours.

Speedway

[edit]Speedway racing was staged at a stadium in New Hammond Beck Road in the 1970s and 1980s. The Boston Barracudas raced in the British League Division Two, (now the Premier League) and in 1973 won the League and the Knock-out Cup, with one member winning the League Individual Championship.[citation needed] After the New Hammond Beck Road Stadium was sold for redevelopment in 1988, attempts to secure a new venue in the 1990s failed. A team, known as Boston, raced in the Conference League at King's Lynn.

An advert for a speedway meeting on Thursday 16 July at the greyhound track in Shodfriers Lane in 1936 appeared in The Guardian on 10 July 1936. Other sources now confirm this was a grass track venue.

Swimming

[edit]Boston Amateur Swimming Club holds galas and open meets, including the Boston Open, and two yearly club championship events. It trains at the Geoff Moulder Swimming Pool.

Sailing

[edit]Witham Sailing Club is based on the banks of the Witham, with its own clubhouse.

Media

[edit]Boston has two weekly newspapers, the Boston Standard[57] and the Boston Target.[58] The Boston Standard (previously Lincolnshire Standard) was founded in the 19th century and has been the main newspaper. The Boston Target is owned by Local World, and is Boston Standard's main rival.

The town is served by a community radio station, Endeavour FM.[59] It had previously been called Endeavour Online and Stump Radio, set up as a collaboration between Blackfriars Arts Centre and Tulip Radio, which first started broadcasting in 2006 on 107 FM.

Education

[edit]Secondary schools

[edit]Boston Grammar School an all-male selective school, is on Rowley Road. Its female counterpart, Boston High School is on Spilsby Road. Both schools have sixth forms open to both boys and girls. Haven High Academy is on Marian Road, and another campus on Tollfield Road – it was created in 1992 on the site of Kitwood Girls' School following its merger with another secondary modern school, Kitwood Boys' School. The town previously also had a Roman Catholic secondary school, St Bede's in Tollfield Road (now the Tollfield Campus operated by Haven High Academy), but this was closed in 2011 following poor exam results.

Colleges

[edit]Boston College is a predominantly further education college that opened in 1964 to provide A-level courses for those not attending the town's two grammar schools. It currently has three sites in the town. It also took over the site of Kitwood Boys' school in Mill Road following the school's merger with Kitwood Girls' School in 1992, but this was closed in 2012, with the buildings subsequently demolished and housing built on the site.

Independent schools

[edit]St George's Preparatory School is the only independent school in the town. Established in 2011, it is housed in a Grade II listed building, the former home of the town architect William Wheeler, and caters for the 3–11 year age group.[60]

Notable Bostonians

[edit]Politics

[edit]

- Anthony Irby (1547–1625) lawyer and politician[61] sat in the House of Commons for Boston variously from 1589 to 1622

- William Ellis (1609–1680) lawyer,[62] judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons for Boston and Grantham variously between 1640 and 1679

- Herbert Ingram (1811–1860) journalist and politician, founder of The Illustrated London News[63]

- William Garfit (1840–1920) banker and Conservative politician,[64] MP for Boston 1895 to 1906

- Fred Maddison (1856–1937) trade unionist[65] and Liberal politician

- Sir Walter Liddall (1884–1963) Conservative MP[66] for Lincoln from 1931 to 1945

- John McNair (1887–1968) socialist politician[67]

- David Ward (born 1953) Liberal Democrat politician,[68] MP for Bradford East 2010 to 2015

- Robin Hunter-Clarke (born 1992) UKIP[69] politician

Church

[edit]- Sir Thomas Dingley (executed 1539) Catholic martyr[70]

- Simon Patrick (1626–1707) theologian[71] and bishop

- Joseph Farrow (1652–1692) nonconformist[72] clergyman

- Andrew Kippis (1725–1795) nonconformist clergyman[73] in Boston (1746 to 1750) and biographer

- John Platts (1775–1837) Unitarian minister[74] and author, a compiler of reference works

- John James Raven (1833–1906) cleric and headmaster,[75] known as a writer on campanology

Public service

[edit]

- Sir Richard Weston (1465–1541) courtier and diplomat,[76] Governor of Guernsey

- John Foxe (1516/17–1587) historian[77] and martyrologist

- Edmund Ingalls (ca.1598–1648) emigrated to Salem in 1628 and founded Lynn, Massachusetts

- John Leverett (1616–1678/9) colonial magistrate,[78] merchant, soldier and governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

- George Bass (1771–1803 presumed) naval surgeon[79] and explorer of Australia

- John R. Jewitt (1783–1821) an armourer in Canada,[80] wrote memoirs of his captivity by local indigenous people

- James Richardson (1809–1851) explored Africa,[81] published his travel notes and diaries

- Frederick Flowers (1810–1886) police[82] magistrate.

- John Conington (1825–1869) classical scholar[83]

- William Henry Wheeler (1832–1915), civil engineer architect, inventor and antiquarian

- Major Walter George Burnett Dickinson (1858–1914)[84] veterinary surgeon

- Arthur James Grant (1862–1948) historian[85]

- Arthur Callender (1875–1936) engineer and archaeologist,[86] assisted Howard Carter in excavating Tutankhamun's tomb

- Janet Lane-Claypon, Lady Forber (1877–1967) physician[87] and epidemiologist

- Hedley Adams Mobbs (1891–1970), architect and philatelist

- Joseph Langley Burchnall (1892–1975) mathematician, introduced Burchnall–Chaundy theory

- Air Vice-Marshal Arthur Lee (1894–1975) senior[citation needed] RAF officer and autobiography writer

- Henry Neville Southern (1908–1986) ornithologist[88]

- Victor Emery (1934–2002) specialist[89] on superconductors and superfluidity

- Richard Budge (1947–2016) coal mining entrepreneur[90]

- John Cridland (born 1961) former Director-General of the Confederation of British Industry, Chair of Transport for the North

- Sir Jonathan Van-Tam (born 1964), Deputy Chief Medical Officer for England during the COVID-19 pandemic

Arts and writing

[edit]

- John Taverner (c1490–1545) composer[91] and organist

- Pishey Thompson (1784–1862) publisher[92] and antiquarian writer

- George French Flowers (1811–1872) composer[93] and musical theorist, promoted counterpoint

- John Westland Marston (1819–1890) dramatist[94] and critic

- Jean Ingelow (1820–1897) poet[95] and novelist

- Elizabeth Jennings (1926–2001) poet[96]

- Barry Spikings (born 1939) film producer,[97] incl. 1978 film, The Deer Hunter

- Pamela Buchner (born 1939) actress

- Mary Farmer (born 1940 Newbury, Berkshire - Died 2021 Boston, Lincolnshire) UK-based designer and weaver of tapestries and rugs[98]

- Dusty Hughes (born 1947) playwright[99] and director, writing for both the theatre and television

- Brian Bolland (born 1951) comics artist[100] produced most of his work for DC Comics

- Alan Moulder (born 1959) record producer,[101] mixing engineer and audio engineer

- Hilary McKay (born 1959) writer[102] of children's books

- Wyn Harness (1960–2007) journalist[103] at The Independent from its creation in 1986

- Amanda Drew (born 1969) actress,[104] plays May Wright in the BBC soap opera EastEnders

- Robert Webb (born 1972) comedian,[105] actor and writer, one half of Mitchell and Webb

- Carl Hudson (born 1983) pianist and keyboardist

- Georgina Callaghan (born 1986) singer-songwriter,[106] currently lives in Nashville

- Courtney Bowman (born 1995) stage actress and singer[107]

Sport

[edit]

- Bill Julian (1867–1957) football player[108] and coach

- Cyril Bland (1872–1950) first class cricketer

- Jack Manning (1886–1946) footballer who scored 31 goals from 218 appearances

- Bernard Codd (c1933–2013) motorcycle road racer, double winner at the 1956 Isle of Man TT motorcycle race

- Mike Pinner (born 1934) international amateur football goalkeeper, 1956 and 1960 Olympics

- Gordon Bolland (born 1943) retired footballer, was player-manager of Boston United F.C.

- Simon Garner (born 1959) former footballer,[109] 474 pro appearances for Blackburn Rovers F.C.

- Simon Clark (born 1967) former footballer[110] and manager, now coach at Charlton Athletic F.C.

- Howard Forinton (born 1975) footballer,[111] approx. 300 pro appearances

- Matt Hocking (born 1978) football defender,[112] over 300 pro appearances

- John Oster (born 1978) former footballer,[113] made 487 pro appearances

- Danny Butterfield (born 1979) former footballer,[114] 488 pro appearances

- Anthony Elding (born 1982) professional footballer,[115] over 400 pro appearances

- Melanie Marshall (born 1982) Olympic athlete, European Gold Medal-winning swimmer, now coach to Olympic Gold medal winner Adam Peaty[116]

- Hannah Macleod (born 1984) field hockey player[117]

- Crista Cullen (born 1985) Olympic Gold Medal winning[118] English field hockey player

- Dave Coupland (born 1986) professional golfer

- Simon Lambert (born 1989) speedway[119] rider

- Emma Bristow (born 1990) motorcycle trials rider and current Women's World Champion

- Scott Williams (born 1990), darts player

- Kieran Tscherniawsky (born 1992) paralympian athlete,[120] category F33 discus

- Ollie Chessum (born 2000), rugby player

Crime

[edit]- William Frederick Horry (1843–1872) murderer,[121] first to be executed by the long drop method

Town twinning and association

[edit]Boston joined the new Hanseatic League, in July 2015, a project for trade, cultural and educational integration. Boston's twin towns include:

- Boston, Massachusetts, United States[citation needed]

- Laval, France; Boston's link with Laval is one of the oldest twinnings in the world.[citation needed]

- Hakusan, Japan

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Holbeach No.2,[a] (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1991–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.9 (58.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

28.0 (82.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

29.1 (84.4) |

34.1 (93.4) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.9 (84.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

34.1 (93.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

8.1 (46.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

1.7 (35.1) |

3.0 (37.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.4 (54.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

2.1 (35.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.1 (19.2) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

1.3 (34.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

4.8 (40.6) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 50.8 (2.00) |

38.5 (1.52) |

36.0 (1.42) |

42.5 (1.67) |

50.7 (2.00) |

57.9 (2.28) |

57.7 (2.27) |

64.2 (2.53) |

52.6 (2.07) |

63.3 (2.49) |

56.5 (2.22) |

52.5 (2.07) |

623.1 (24.53) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.0 | 9.6 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 8.5 | 10.8 | 11.6 | 11.0 | 116.9 |

| Source 1: Met Office[122] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Starlings Roost Weather[123] | |||||||||||||

Destinations

[edit]See also

[edit]- Boston United F.C.

- Dynamic Cassette International

- Endeavour FM – community radio station

- List of road protests in the UK and Ireland – Boston Bypass is listed

Notes

[edit]- ^ Weather station is located 10.0 miles (16.1 km) from the Boston town centre.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Cite error: The named reference

keywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Boston (Lincolnshire, East Midlands, United Kingdom) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "Census 2021 Key Statistics, Urban areas in England and Wales". citypopulation.de. 24 March 2023.

- ^ "Population Estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: mid-2015" (Excel). Office for National Statistics. 23 June 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Church sells bits of Boston Stump". BBC News. 3 November 2005. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g EB (1878).

- ^ "Key to English Place-names". Key to English Place-Names. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ Plea Rolls of the court of Common Pleas: CP40/797; second entry up from the bottom; lines 1 and 2

- ^ a b c d e f g h EB (1911), p. 290.

- ^ Morris (1986), Landowner 12, §67.

- ^ Morris (1979), p. 101.

- ^ Thompson (1856), Div. VIII.

- ^ Borough of Boston. Official Guide to Boston. Ed J Burrow & Co Ltd. p. 13 paragraph 1.

- ^ a b H. W. Nicholson, ed. (1986). A Short History Of Boston (4th ed.). Guardian Press of Boston. p. 2.

- ^ J.B.Priestley English Journey 1934 p.373 "When Boston was a port of some importance-and at one time, in the 13th century, it was the second port in the country..."

- ^ Thompson (1856).

- ^ a b "John Cotton | Puritan Minister, Massachusetts Bay Colony | Britannica". britannica.com. 17 September 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ Morrow, Daniel (20 November 2018). "Fogarty name to continue despite job losses from Boston firm". Lincolnshire Live. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ a b [1] CWGC Cemetery Report, Boston Cemetery.

- ^ Hurt, Fred (1994). Lincolnshire and Newark in the Wars. W.J. Harrison, Lincoln. pp. 133–134.Chapter – Zeppelins WWI.

- ^ "A History of Boston". localhistories.org. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ [2] CWGC Cemetery Report, Boston Municipal Borough.

- ^ "Boston General Hospital". National Archives. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ "Obituary: Sir George Grenfell-Baines". The Telegraph. 3 June 2003. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ "Design and access statement" (PDF). Boston Council. p. 3. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ "Timetables". East Midlands Railway. 2 June 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ "Boston Bus Services". Bus Times. 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ "EU referendum results". The Financial Times Ltd. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ "Your Councillors". 10 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Bypass group wins race for Boston". BBC. 4 May 2007. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- ^ Moore, Walter (11 November 2018). Boston (Lincolnshire) and Its Surroundings: With an Account of The Pilgrim Fathers of New England. Franklin Classics Trade Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9780353402041.

- ^ "Boston Registration District". ukbmd.org.uk. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Municipal Offices, West Street, Boston". Lincolnshire Heritage Explorer. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ "Boston Borough Council". Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Brexitland versus Londonia". Economist. 2 July 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "John Foxe". Boston Preservation Trust. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ The Oxford Book of National Biography – September 2004, quoted on The Early History of The Illustrated London News

- ^ "'Waiting for the Waves to Give Up Their Dead,'". Chicago Tribune. 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Hussey Tower". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ Historic England. "Rochford Tower (353869)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ "Location of Greenwich Meridian marker: Lincolnshire, Boston". www.thegreenwichmeridian.org. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "College art to take over Boston gallery". Boston Target. 22 May 2013. p. 6. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Blackfriars Theatre and Arts Centre". blackfriarsartscentre.co.uk.

- ^ "Frampton Marsh". rspb.org.uk. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ "Freiston Shore". rspb.org.uk. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ "Sir George Gilbert Scott". Boston Preservation Trust. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "Scott House". Boston Preservation Trust.

- ^ "The Arbor Club". Boston Preservation Trust. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "The Warehouse". Boston Preservation Trust. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "Refurbishment of Boston Market Place". Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ (Mr) SKDC Details, Council Offices (26 January 2012). "Boston Market". Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "The most murderous place in England and Wales may surprise you". The Independent. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "Do you live in this town? It's the murder capital of England and Wales". Metro. 23 January 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "Boston named '˜most murderous' town in England and Wales". bostonstandard.co.uk. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Carter, Helen (12 October 2006). "Lincolnshire: home of the porker?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- ^ Boston Standard, 9 July 2020, "The aim is to give them the best ground we can!"... retrieved 27 July 2020

- ^ Boston Standard

- ^ "Boston Target". Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Boston's 107 Endeavour FM | About Us". endeavourfm.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Welcome to St George's Preparatory School, Boston". Boston, Lincolnshire: St George's Preparatory School and Little Dragons Nursery. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ The History of Parliament Trust, IRBY, Anthony (1547–1625) retrieved 17 January 2018

- ^ The History of Parliament Trust, ELLYS (ELLIS), William (1607–80) retrieved 17 January 2018

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 29. 1892.

- ^ Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by William Garfit retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ Hansard 1803–2005, contributions in Parliament by Fred Maddison retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ Hansard 1803–2005, contributions in Parliament by Sir Walter Liddall retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ Who Was Who, McNAIR, John retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ TheyWorkForYou, David Ward, Former MP, Bradford East retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ BBC News, 20 November 2014, Boston and Skegness UKIP vote... retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 04. 1908.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 18. 1889.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 31. 1892.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 45. 1896.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). 1912.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 60. 1899.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, LEVERETT, JOHN retrieved 17 January 2018

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 03. 1885.

- ^ Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, Volume VI (1821–1835), JEWITT, JOHN RODGERS retrieved 17 January 2018

- ^ Works by James Richardson, Project Gutenberg retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 19. 1889.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 06 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ CWGC Archive Online, Commonwealth War Graves Commission retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ UK National Archives, Archival material relating to Arthur James Grant retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ Dawson, W; Uphill, E (1972). Who Was Who in Egyptology, 2nd edition. Egypt Exploration Society, London. p. 50. ISBN 0856981257. OCLC 470552591.

- ^ British Medical Journal, 29 July 1967, Obituary Notices retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ "H. N. Southern". Ibis. 129: 281–282. 1987. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1987.tb03209.x.

- ^ The Old Bostonian Association, Victor Emery Archived 4 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 4 May 2018

- ^ Brighouse Echo, 18 July 2016, King Coal mining mogul.... Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, John Taverner retrieved 16 January 2018

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 56. 1898.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 19. 1889.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 36. 1893.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ Poetry nation No 5 1975, The Poetry of Elizabeth Jennings retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ Farmer, Mary; Moores, Terry (21 November 1985). "Old warehouse a home of arts". The Boston Standard.

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ The Polymath Perspective, Assault & Battery 2 Studios: Alan Moulder retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ British Council, Literature, Hilary McKay retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ The Independent, 5 October 2007, Obituaries, Wyn Harness retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ "Six the Musical". sixthemusical.com. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Scobo.co.uk., Bill Julian Archived 30 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ SoccerBase Database retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ SoccerBase Database retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ SoccerBase Database retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ SoccerBase Database retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ SoccerBase Database retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ SoccerBase Database retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ SoccerBase Database retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ "Mel Marshall Is Coach Of The Year In Britain After Stellar Season For Her & Adam Peaty". 21 February 2016. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ GB Hockey, Player Profile, Hannah Macleod Archived 21 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ GB Hockey, Player Profile, Crista Cullen Archived 13 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ BBC Sport, 29 September 2010, retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ www.paralympic.org, Tscherniawsky, Kieran Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 18 January 2018

- ^ William Frederick Horry, History in the making, www.capitalpunishmentuk.org retrieved 19 January 2018

- ^ "Station: Holbeach No 2, Climate period: 1991–2020". Met Office. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "Monthly Extreme Maximum Temperature, Monthly Extreme Minimum Temperature". Starlings Roost Weather. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 4 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 72

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 4 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 289–290

- Morris, Anthony Edwin James (1979), History of Urban Form: Before the Industrial Revolution, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-7114-5512-2

- Morris, John, ed. (1986), Domesday Book, Vol. 31: Lincolnshire, Chister: Phillimore, originally collected 1086, ISBN 978-0-85033-598-9

- Rigby, S.H., ed. (2017), Boston, 1086-1225: A Medieval Boom Town, The Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, ISBN 978-0-903582-56-8

- Rigby, S.H., ed. (2005), The Overseas Trade of Boston in the Reign of Richard II, Lincoln Record Society, No. 93, Woodbridge: Boydell, ISBN 978-0-901503-74-9

- Thompson, Pishey (1820), Collections for a Topographical and Historical Account of Boston, and the Hundred of Skirbeck, Boston: J. Noble

- Thompson, Pishey (1856), The History and Antiquities of Boston..., Boston, ISBN 978-0-948639-20-3

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

[edit]- Boston Farmers Union and Other Papers, History of Boston series, no. 3 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1971).

- The First Stone and Other Papers, History of Boston series, no. 1 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1970).

- Badham, Sally, and Paul Cockerham (eds.), "The Beste and Fayrest of Al Lincolnshire": The Church of St Botolph, Boston, Lincolnshire, and Its Medieval Monuments, British Archaeological Reports, British Series, no. 554 (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2012).

- Bagley, George S., Floreat Bostona: History of Boston Grammar School from 1567 (Boston: Old Bostonian Association, 1985).

- Bagley, G. S., Boston: Its Story and People (Boston: History of Boston Project, 1986).

- Clark, Peter, and Jennifer Clark (eds.), The Boston Assembly Minutes, 1545–1575, Publications of the Lincoln Record Society, no. 77 (Woodbridge: Boydell for the Lincoln Record Society, 1986).

- Cook, A. M., Boston, Botolph's Town: A Short History of a Great Parish Church and Town About It (Boston: Church House, 1948).

- Cross, Claire, "Communal piety in sixteenth-century Boston", Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, vol. 25 (1990), pp. 33–38.

- Davis, S. N., Banking in Boston, History of Boston series, no. 14 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1976).

- Dover, Percy, The Early Medieval History of Boston, AD 1086–1400, History of Boston series, no. 2 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1972).

- Garner, Arthur A., Boston and the Great Civil War, 1642–1651, History of Boston series, no. 7 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1972).

- Garner, Arthur A., Boston, Politics and the Sea, 1652–1674, History of Boston series, no. 13 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1975).

- Garner, Arthur A., The Fydells of Boston (Boston: Richard Kay, 1987).

- Garner, Arthur A., The Grandest House in Town (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 2002).

- Gurnham, Richard, The Story of Boston (Stroud: The History Press, 2014).

- Hinton, R. W. K., The Port Books of Boston, 1601–40, Publications of the Lincoln Record Society, no. 50 (Lincoln: Lincoln Record Society, 1956).

- Jebb, G., The Church of St Botolph, Boston (Boston, 1895).

- Leary, William, Methodism in the Town of Boston, History of Boston series, no. 6 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1972).

- Lewis, M. R. T., and Neil R. Wright, "Boston as a Port", Proceedings of the 7th East Midlands Industrial Archaeology Conference, vol. 8, no. 4 (1973).

- Lloyd, T. H., The English Wool Trade in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977).

- Middlebrook, Martin, Boston at War: Being an Account of Boston's Involvement in the Boer War and the Two World Wars, History of Boston series, no. 12 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1974).

- Middlebrook, Martin, The Catholic Church in Boston, History of Boston series, no. 15 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1977).

- Minnis, John, Katie Carmichael and Clive Fletcher, Boston, Lincolnshire: Historic North Sea Port and Market Town (Swindon: Historic England, 2015).

- Molyneux, Frank H. (ed.), Aspects of Nineteenth-Century Boston and District, History of Boston series, no. 8 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1972).

- Molyneux, Frank, and Neil R. Wright, An Atlas of Boston, History of Boston series, no. 10 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1974).

- Ormrod, Mark, and others, Boston Blackfriars (Boston: Pilgrim College, 1990).

- Ormrod, Mark, and others, The Guilds in Boston (Boston: Pilgrim College, 1993).

- Owen, Dorothy M., Church and Society in Medieval Lincolnshire, History of Lincolnshire, no. 5 (Lincoln: History of Lincolnshire Committee of the Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 1971).

- Owen, Dorothy M., "The Beginnings of the port of Boston", in Naomi Field and Andrew White, A Prospect of Lincolnshire (Lincoln: privately published, 1984).

- Power, Eileen, The Wool Trade in English Medieval History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1941).

- Rigby, Stephen H., "Boston and Grimsby in the Middle Ages: An administrative contrast", Journal of Medieival History, vol. 10, no. 1 (1984), pp. 51–66.

- Rigby, Stephen H., "'Sore decay' and 'fair dwellings': Boston and urban decline in the later Middle Ages", Midland History, vol. 10, no. 1 (1985), pp. 47–61.

- Rigby, Stephen H., "The customs administration at Boston in the reign of Richard II", Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, vol. 58, no. 137 (1985), pp. 12–24.

- Rigby, Stephen H., The Overseas Trade of Boston in the Reign of Richard II, Publications of the Lincoln Record Society, no. 93 (Woodbridge: Boydell for the Lincoln Record Society, 2007).

- Rigby, Stephen H., Boston, 1086–1225: A Medieval Boom Town (Lincoln: Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 2017).

- Robinson, Lionel, Boston's Newspapers, History of Boston series, no. 11 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1974).

- Spurrell, Mark, The Puritan Town of Boston and Other Papers, History of Boston series, no. 5 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1972).

- Summerson, H., "Calamity and Commerce: the Burning of Boston Fair in 1288", in Caroline M. Barron and Anne F. Sutton (eds), The Medieval Merchant: Proceedings of the 2012 Harlaxton Symposium, Harlaxton Medieval Studies, no. 24 (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2014), pp. 146–165.

- Thompson, Pishey, The History and Antiquities of Boston and the Hundred of Skirbeck (Boston, 1856).

- Turpin, Hubert, Boston Grammar School: A Short History (Boston: Guardian Press, 1966).

- Tyszka, Dinah, Keith Miller and Geoffrey Bryant (eds.), Land, People and Landscapes: Essays on the History of the Lincolnshire Region Written in Honour of Rex C. Russell (Lincoln: Lincolnshire Books, 1991).

- Wheeldon, Jeremy, The Monumental Brasses in Saint Botolph's Church, Boston, History of Boston, no. 9 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1973).

- Wilson, Eleanora Carus-, "The Medieval Trade of the Ports of the Wash", Medieval Archaeology, vol. 6, no. 1 (1962), pp. 182–201.

- Wilson, Eleanora Carus-, and Olive Coleman, England's Export Trade, 1275–1547 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963).

- Wright, Neil R., The Railways of Boston: Their Origins and Development, History of Boston series, no. 4 (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston Project, 1971); 2nd ed. (Boston: Richard Kay for the History of Boston, 1998).

- Wright, Neil R., Lincolnshire Towns and Industry, 1700–1914, History of Lincolnshire, no. 11 (Lincoln: History of Lincolnshire Committee of the Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 1982).

- Wright, Neil R., The Book of Boston (Buckingham: Barracuda, 1986).

- Wright, Neil R., "The Varied Fortunes of Heavy and Manufacturing Industry 1914–1987", in Dennis Mills (ed.), Twentieth Century Lincolnshire, History of Lincolnshire, no. 12 (Lincoln: History of Lincolnshire Committee of the Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 1989), pp. 74–102.

- Wright, Neil R., Boston: A History and Celebration (Salisbury: The Francis Frith Collection, 2005).

- Wright, Neil R., Boston by Gaslight: A History of Boston Gas Undertaking since 1825 (Boston: R. Kay, 2002).

External links

[edit]Wikisource

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 04 (11th ed.). 1911.