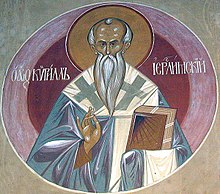

Cyril of Jerusalem

Cyril of Jerusalem | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bishop, Confessor and Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | c. AD 313 possibly near Caesarea Maritima, Syria Palaestina |

| Died | AD 386 (aged 73) Jerusalem, Syria Palaestina |

| Venerated in | |

| Feast |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

Cyril of Jerusalem (Greek: Κύριλλος Α΄ Ἱεροσολύμων, Kýrillos A Ierosolýmon; Latin: Cyrillus Hierosolymitanus; c. 313[3] – 386) was a theologian of the Early Church. About the end of AD 350, he succeeded Maximus as Bishop of Jerusalem, but was exiled on more than one occasion due to the enmity of Acacius of Caesarea, and the policies of various emperors. Cyril left important writings documenting the instruction of catechumens and the order of the Liturgy in his day.

Cyril is venerated as a saint within the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Church, and the Anglican Communion. In 1883, Cyril was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Leo XIII.

Cyril is remembered in the Church of England with a commemoration on 18 March.[4] He should not be confused with Cyril of Alexandria.

Life and character

[edit]Little is known of his life before he became a bishop; the assignment of his birth to the year 315 rests on conjecture.[5] According to Butler, Cyril was born at or near the city of Jerusalem and was well-read in both the writings of the early Christian theologians and the Greek philosophers.[6]

Cyril was ordained a deacon by Bishop Macarius of Jerusalem in about 335 AD and a priest some eight years later by Bishop Maximus. Around the end of 350 AD, he succeeded Maximus in the See of Jerusalem, although the evidence for this relies on the Catecheses written by Cyril where he refers to himself as "bishop". Jerome also suggests Cyril was an Arian at this stage.[7][8][9]

Cyril is described as a preacher and liturgist by the pilgrim Egeria.[10]

Episcopacy

[edit]Relations between Metropolitan Acacius of Caesarea and Cyril became strained. Acacius is presented as a leading Arian by the orthodox historians, and his opposition to Cyril in the 350s is attributed by these writers to this. Sozomen also suggests that the tension may have been increased by Acacius's jealousy of the importance assigned to Cyril's See by the Council of Nicaea, as well as by the threat posed to Caesarea by the rising influence of the seat of Jerusalem as it developed into the prime Christian holy place and became a centre of pilgrimage.[11]

Acacius charged Cyril with selling church property.[12] The city of Jerusalem had suffered drastic food shortages at which point church historians Sozomen and Theodoret report "Cyril secretly sold sacramental ornaments of the church and a valuable holy robe, fashioned with gold thread that the emperor Constantine had once donated for the bishop to wear when he performed the rite of Baptism",[13] possibly to keep people from starving.

For two years, Cyril resisted Acacius' summons to account for his actions, but a church council held under Acacius's influence in 357 AD deposed Cyril in his absence, and Cyril took refuge with Silvanus, Bishop of Tarsus.[14] The following year, 359 AD, in an atmosphere more hostile to Acacius, the Council of Seleucia reinstated Cyril and deposed Acacius. In 360 AD, this was reversed by Emperor Constantius again,[15] and Cyril suffered another year's exile from Jerusalem until the Emperor Julian's accession allowed him to return in 361.[16]

Cyril was once again banished from Jerusalem by the Arian Emperor Valens in 367 AD but was able to return again after Valens's death in 378 AD, after which he remained undisturbed until his death in 386. In 380 AD, Gregory of Nyssa came to Jerusalem on the recommendation of a council held at Antioch in the preceding year. He seemingly found the faith in good shape, but worried that the city was prey to parties and corrupt in morals.[17] Cyril's jurisdiction over Jerusalem was expressly confirmed by the First Council of Constantinople (381), at which he was present.[18] At that council he voted for acceptance of the term homoousios (which defined the nature between "God the Father", and "God the Son"), having been finally convinced that there was no better alternative.[7] His story is perhaps best representative of those Eastern bishops (perhaps a majority) initially mistrustful of Nicaea, who came to accept the creed of that council, and the doctrine of the homoousion.[19]

Theological position

[edit]Though his theology was at first somewhat indefinite in phraseology, he undoubtedly gave a thorough adhesion to the Nicene Orthodoxy. Even if he did avoid the debatable term homoousios, he expressed its sense in many passages, which exclude equally Patripassianism, Sabellianism, and the formula "there was a time when the Son was not" attributed to Arius.[17] In other points he takes the ordinary ground of the Eastern Fathers, as in the emphasis he lies on the freedom of the will, the autexousion (αὐτεξούσιον), and in his view of the nature of sin. To him sin is the consequence of freedom, not a natural condition. The body is not the cause, but the instrument of sin. The remedy for it is repentance, on which he insists. Like many of the Eastern Fathers, he focuses on high moral living as essential to true Christianity. His doctrine of the Resurrection is not quite so realistic as that of other Fathers; but his conception of the Church is decidedly empirical: the existing Church form is the true one, intended by Christ, the completion of the Church of the Old Testament. His interpretation of the Eucharist is disputed. Some argue he sometimes seems to approach the symbolic view, though he professes a strong realistic doctrine. The bread and wine are not mere elements, but the body and blood of Christ.[20]

Cyril's writings are filled with the loving and forgiving nature of God which was somewhat uncommon during his time period. Cyril fills his writings with great lines of the healing power of forgiveness and the Holy Spirit, like "The Spirit comes gently and makes himself known by his fragrance. He is not felt as a burden for God is light, very light. Rays of light and knowledge stream before him as the Spirit approaches. The Spirit comes with the tenderness of a true friend to save, to heal, to teach, to counsel, to strengthen and to console". Cyril himself followed God's message of forgiveness many times throughout his life. This is most clearly seen in his two major exiles where Cyril was disgraced and forced to leave his position and his people behind. He never wrote or showed any ill will towards those who wronged him. Cyril stressed the themes of healing and regeneration in his catechesis.[21]

Catechetical lectures

[edit]

Cyril's famous twenty-three lectures given to catechumens in Jerusalem being prepared for, and after, baptism are best considered in two parts: the first eighteen lectures are commonly known as the Catechetical Lectures, Catechetical Orations or Catechetical Homilies, while the final five are often called the Mystagogic Catecheses (μυσταγωγικαί), because they deal with the mysteries (μυστήρια) i.e. Sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation and the Eucharist.[22]

His catechetical lectures (Greek Κατηχήσεις, Katēchēseis)[23] are generally assumed, on the basis of limited evidence, to have been delivered either in Cyril's early years as a bishop, around 350 AD, or perhaps in 348 AD, while Cyril was still a priest, deputising for his bishop, Maximus.[24] The Catechetical Lectures were given in the Martyrion, the basilica erected by Constantine.[19] They contain instructions on the principal topics of Christian faith and practice, in a popular rather than scientific manner, full of a warm pastoral love and care for the catechumens to whom they were delivered. Each lecture is based upon a text of Scripture, and there is an abundance of Scriptural quotation throughout. In the Catechetical Lectures, parallel with the exposition of the Creed as it was then received in the Church of Jerusalem are vigorous polemics against pagan, Jewish, and heretical errors. They are of great importance for the light which they throw upon the method of instruction usual of that age, as well as upon the liturgical practises of the period, of which they give the fullest account extant.[18]

It is not only among us, who are marked with the name of Christ, that the dignity of faith is great; all the business of the world, even of those outside the Church, is accomplished by faith. By faith, marriage laws join in union persons who were strangers to one another. By faith, agriculture is sustained; for a man does not endure the toil involved unless he believes he will reap a harvest. By faith, seafaring men, entrusting themselves to a tiny wooden craft, exchange the solid element of the land for the unstable motion of the waves."[25]

In the 13th lecture, Cyril of Jerusalem discusses the Crucifixion and burial of Jesus Christ. The main themes that Cyril focuses on in these lectures are Original sin and Jesus' sacrificing himself to save us from our sins. Also, the burial and Resurrection which occurred three days later proving the divinity of Jesus Christ and the loving nature of the Father. Cyril was very adamant about the fact that Jesus went to his death with full knowledge and willingness. Not only did he go willingly but throughout the process he maintained his faith and forgave all those who betrayed him and engaged in his execution. Cyril writes "who did not sin, neither was deceit found in his mouth, who, when he was reviled, did not revile, when he suffered did not threaten".[26] This line by Cyril shows his belief in the selflessness of Jesus especially in this last final act of Love. The lecture also gives a sort of insight to what Jesus may have been feeling during the execution from the whippings and beatings, to the crown of thorns, to the nailing on the cross. Cyril intertwines the story with the messages Jesus told throughout his life before his execution relating to his final act. For example, Cyril writes "I gave my back to those who beat me and my cheeks to blows; and my face I did not shield from the shame of spitting".[27] This clearly reflects the teachings of Jesus to turn the other cheek and not raising your hands against violence because violence just begets violence begets violence. The segment of the Catechesis really reflects the voice Cyril maintained in all of his writing. The writings always have the central message of the Bible; Cyril is not trying to add his own beliefs in reference to religious interpretation and remains grounded in true biblical teachings.

Danielou sees the baptism rite as carrying eschatological overtones, in that "to inscribe for baptism is to write one's name in the register of the elect in heaven".[28]

Eschatology

[edit]Oded Irshai observed that Cyril lived in a time of intense apocalyptic expectation, when Christians were eager to find apocalyptic meaning in every historical event or natural disaster. Cyril spent a good part of his episcopacy in intermittent exile from Jerusalem. Abraham Malherbe argued that when a leader's control over a community is fragile, directing attention to the imminent arrival of the antichrist effectively diverts attention from that fragility.[29]

Soon after his appointment, Cyril in his Letter to Constantius[30] of 351 AD recorded the appearance of a cross of light in the sky above Golgotha, witnessed by the whole population of Jerusalem. The Greek church commemorates this miracle on 7 May. Though in modern times the authenticity of the Letter has been questioned, on the grounds that the word homoousios occurs in the final blessing, many scholars believe this may be a later interpolation, and accept the letter's authenticity on the grounds of other pieces of internal evidence.[31]

Cyril interpreted this as both a sign of support for Constantius, who was soon to face the usurper Magnentius, and as announcing the Second Coming, which was soon to take place in Jerusalem. Not surprisingly, in Cyril's eschatological analysis, Jerusalem holds a central position.[32]

Matthew 24:6 speaks of "wars and reports of wars", as a sign of the End Times, and it is within this context that Cyril read Julian's war with the Persians. Matthew 24:7 speaks of "earthquakes from place to place", and Jerusalem experienced an earthquake in 363 at a time when Julian was attempting to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem.[29] Embroiled in a rivalry with Acacius of Caesarea over the relative primacy of their respective sees, Cyril saw even ecclesial discord a sign of the Lord's coming.[33] Catechesis 15 would appear to cast Julian as the antichrist, although Irshai views this as a later interpolation.[29]

"In His first coming, He endured the Cross, despising shame; in His second, He comes attended by a host of Angels, receiving glory. We rest not then upon His first advent only, but look also for His second."[34] He looked forward to the Second Advent which would bring an end to the world and then the created world to be made anew. At the Second Advent he expected to rise in the resurrection if it came after his time on earth.[35]

Mystagogic Catecheses

[edit]There has been considerable controversy over the date and authorship of the Mystagogic Catecheses, addressed to the newly baptized, in preparation for the reception of Holy Communion, with some scholars having attributed them to Cyril's successor as Bishop of Jerusalem, John.[36] Many scholars would currently view the Mystagogic Catecheses as being written by Cyril, but in the 370s or 380s, rather than at the same time as the Catechetical Lectures.[37]

According to the Spanish pilgrim Egeria, these mystagogical catecheses were given to the newly baptised in the Church of the Anastasis in the course of Easter Week.[19]

Works

[edit]Editions

[edit]- W. C. Reischl, J. Rupp (1848; 1860). Cyrilli Hierosolymarum Archiepiscopi opera quae supersunt omnia. München.

- Christa Müller-Kessler and Michael Sokoloff (1999). The Catechism of Cyril of Jerusalem in the Christian Palestinian Aramaic Version, A Corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic, vol. V. Groningen: STYX-Publications. ISBN 90-5693-030-3

- Christa Müller-Kessler (2021). Neue Fragmente zu den Katechesen des Cyrill von Jerusalem im Codex Sinaiticus rescriptusi (Georg. NF 19, 71) mit einem zweiten Textzeugen (Syr. NF 11) aus dem Fundus des St. Katherinenklosters, Oriens Christianus 104, pp. 23–66. ISBN 9783447181358

Modern translations

[edit]- Cyril; Gifford, Edwin Hamilton (1894). "Catechetical Lectures of Saint Cyril, Lecture 15, Section 1". In Schaff, Philip; Wace, Henry (eds.). Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. series two. Vol. 7. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co.

- McCauley, Leo P. and Anthony A. Stephenson, (1969, 1970). The works of Saint Cyril of Jerusalem. 2 vols. Washington: Catholic University of America Press [contains an introduction, and English translations of: Vol 1: The introductory lecture (Procatechesis). Lenten lectures (Catecheses). Vol 2: Lenten lectures (Katēchēseis). Mystagogical lectures (Katēchēseis mystagōgikai). Sermon on the paralytic (Homilia eis ton paralytikon ton epi tēn Kolymbēthran). Letter to Constantius (Epistolē pros Kōnstantion). Fragments.]

- Telfer, W. (1955). Cyril of Jerusalem and Nemesius of Emesa. The Library of Christian classics, v. 4. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

- Yarnold, E. (2000). Cyril of Jerusalem. The early church fathers. London: Routledge. [provides an introduction, and full English translations of the Letter to Constantius, the Homily on the Paralytic, the Procatechesis, and the Mystagogic Catechesis, as well as selections from the Lenten Catecheses.]

See also

[edit]- Liturgy of Saint James

- Descriptions in antiquity of the execution cross

- Saint Cyril of Jerusalem, patron saint archive

References

[edit]- ^ Galadza, Daniel (2018). Liturgy and Byzantinization in Jerusalem. Oxford University Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-19-881203-6.

- ^ "March 18: St. Cyril of Jerusalem". Catholic Telegraph. 17 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Walsh, Michael, ed. Butler's Lives of the Saints. (HarperCollins Publishers: New York, 1991), pp. 83.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Johann Jakob Herzog, Philip Schaff (18 March 1909). "The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge: Embracing Biblical, Historical ..." Funk and Wagnalls Company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Butler, Alban (1866) Vol. III, D. & J. Sadlier, & Company (1866). The Lives or the Fathers, Martyrs and Other Principal Saints'. J. Duffy. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b *"Lives of the Saints, For Every Day of the Year" edited by Rev. Hugo Hoever, S.O.Cist., PhD, New York: Catholic Book Publishing Co., 1955, p. 112.

- ^ a.

- ^ Jerome gives a dark account of this appointment, claiming that Cyril was an Arian, and "was offered the see on Maximus' death on the condition that he would repudiate his ordination at the hands of that Bishop".(Yarnold (2000), p4) Jerome had personal reasons for being malicious, though, and, the story may simply be a case of Cyril conforming to proper church order. Young (2004), p186.

- ^ John Wilkinson: Egeria's Travels. Oxbow Books, Oxford 2015. ISBN 978-0-85668-710-5

- ^ Sozomen, HE, 4.25.

- ^ Frances Young with Andrew Teal, From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and its Background, (2nd edn, 2004), p187.

- ^ Drijvers 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Di Berardino, Angelo. 1992. Encyclopedia of the early church. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 312.

- ^ The reasons for this reversal are not entirely clear. According to Theodoret, (HE 2.23), Acacius informed the emperor that one of the things sold by Cyril was a 'holy robe' dedicated by Constantine himself, which consequently turned Constantius against Cyril. The truth of this is not clear though.

- ^ Norris 2007, p. 77.

- ^ a b Henry Palmer Chapman (1908). "St. Cyril of Jerusalem". In Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b "CR Meyer Manpower Planner". crmmanpowerplanner.crmeyer.com.

- ^ a b c Andrew Louth, 'Palestine', in Frances Young et al., The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature, (2010), p284.

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: Catechetical Lecture 22 (Cyril of Jerusalem)". www.newadvent.org.

- ^ Hellemo, Geir (18 March 1989). Adventus Domini: Eschatological Thought in 4th Century Apses and Catecheses. BRILL. ISBN 9004088369 – via Google Books.

- ^ *"The Penguin Dictionary of Saints, 3rd Edition", Donald Attwater and Catherine Rachel John, New York: Peguin Putnam Inc., 1995, p. 101.

- ^ "Philip Schaff: NPNF2-07. Cyril of Jerusalem, Gregory Nazianzen – Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org.

- ^ The main evidence for this dating is that at one point Cyril casually refers to the heresy of Mani as being seventy years old (Cat 6.20). Andrew Louth, 'Palestine', in Frances Young et al., The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature, (2010), p284.

- ^ Cyril, Catechesis V.

- ^ Drijvers 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Drijvers 2004, p. 13-14.

- ^ Bergin, Liam (18 March 1999). O Propheticum Lavacrum. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. ISBN 9788876528279 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Kalleres, Dayna S. (13 October 2015). City of Demons: Violence, Ritual, and Christian Power in Late Antiquity. Univ of California Press. ISBN 9780520956841 – via Google Books.

- ^ English translation is in Telfer (1955).

- ^ Frances Young with Andrew Teal, From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and its Background, (2nd edn, 2004), p192.

- ^ Cain, Andrew; Lenski, Noel Emmanuel (1 January 2009). The Power of Religion in Late Antiquity. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9780754667254 – via Google Books.

- ^ Seminary, Jerry L. Walls Professor of Philosophy of Religion Asbury Theological (31 October 2007). The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780199727636 – via Google Books.

- ^ Cyril & Gifford 1894.

- ^ Froom 1950, pp. 412–415.

- ^ Swaans (1942) makes the main case for an authorship by John; Doval (2001) argues in detail against Swaans's case. The arguments are summarised in Frances Young with Andrew Teal, From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and its Background, (2nd edn, 2004), p189.

- ^ See, for example, Yarnold (1978). Frances Young with Andrew Teal, From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and its Background, (2nd edn, 2004), p190.

Sources

[edit]- Drijvers, Jan Willem (2004). Cyril of Jerusalem: Bishop and City. Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae. Vol. v. 72. Brill.

- Norris, Frederick N. (2007). "Greek Christianities". In Casidy, Augustine; Norris, Frederick W. (eds.). Cambridge History of Christianity. Vol. 2:Constantine to 600c. Cambridge University Press.

- Froom, Le Roy Edwin (1950). Early Church Exposition, Subsequent Deflections, and Medieval Revival. The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers. Vol. 1. p. 1006.

Further reading

[edit]- The Penguin Dictionary of Saints, 3rd Edition, Donald Attwater and Catherine Rachel John, New York: Peguin Putnam Inc., 1995, ISBN 0-14-051312-4

- Lives of the Saints, For Every Day of the Year edited by Rev. Hugo Hoever, S.O.Cist., PhD, New York: Catholic Book Publishing Co., 1955

- Omer Englebert, Lives of the Saints New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1994, ISBN 1-56619-516-0

- Lane, A. N. S., & Lane, A. N. S. (2006). A concise history of Christian thought. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic.

- Van, N. P. (1 January 2007). 'The Career Of Cyril Of Jerusalem (C.348–87): A Reassessment'. The Journal of Theological Studies, 58, 1, 134–146.

- Di Berardino, Angelo. 1992. Encyclopedia of the Early Church. New York: Oxford University Press.

- In Cross, F. L., & In Livingstone, E. A. (1974). The Oxford dictionary of the Christian Church. London: Oxford University Press.

External links

[edit]- "Cyril of Jerusalem" in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- Texts by Cyril (English)

- Collected works by Migne Patrologia Graeca

- Works by Cyril of Jerusalem at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)