St James's Gazette

The St James's Gazette was a London evening newspaper published from 1880 to 1905. It was founded by the Conservative Henry Hucks Gibbs, later Baron Aldenham, a director of the Bank of England 1853–1901 and its governor 1875–1877; the paper's first editor was Frederick Greenwood, previously the editor of the Conservative-leaning Pall Mall Gazette.[1]

The St James's Gazette was bought by Edward Steinkopff, founder of the Apollinaris mineral water company, in 1888. Greenwood left, to be succeeded by Sidney Low (1888–1897), Hugh Chisholm (1897–1899) and Ronald McNeill (1900–1904). Steinkopff sold the paper to C. Arthur Pearson in 1903, who merged it with the Evening Standard in March 1905, ending the paper's daily publication.

A weekly digest of the paper, the St James's Budget, appeared from 3 July 1880 until 3 February 1911.[2]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]

The St James's Gazette was founded in 1880 out of the Pall Mall Gazette, which was (in the phrase of Leslie Stephen, the father of Virginia Woolf) "the most thorough-going of Jingo newspapers."[4] The Pall Mall was owned by George Smith of Smith, Elder & Co., who founded the world-famous Apollinaris mineral water firm with Edward Steinkopff in 1874.[5] In April 1880 Smith (who later founded the Dictionary of National Biography) handed control of the Pall Mall Gazette to his new son-in-law Henry Yates Thompson who, with his editor John Morley (later Viscount Morley), determined to turn it into a radical Liberal paper.[4][6]

In order to continue his advocacy of the old policy of the Pall Mall, H. H. Gibbs[n 1] founded the St James's Gazette, taking Greenwood and the Pall Mall's entire staff; the first issue appeared on 31 May 1880.[7][8]

Publication

[edit]

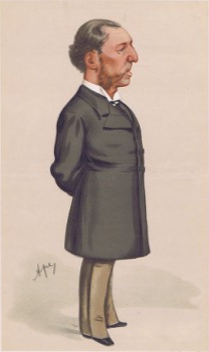

Caricature of Frederick Greenwood by 'Ape' (Carlo Pellegrini) in Vanity Fair, June 1880

In the new paper Frederick Greenwood fought for the same cause with the same spirit and capacity as in the old. He powerfully advocated the occupation of Egypt in 1882, and was the whole-hearted opponent of the Irish nationalists. One occasional contributor to this 'strongest of Tory voices' was the critic George Saintsbury.[7] No newspaper helped more effectively to destroy W. E. Gladstone's power and to prepare the way for the long predominance of the Liberal Unionist Party. But various causes, of which the strongest was the decline of a taste for serious journalism in the public, rendered it impossible for the St James's to attain to the prosperity of the Pall Mall.[4]

After the death of one of the proprietors, George Gibbs, on 26 November 1886 the financial control passed to his cousin Henry Gibbs, who was not equally in harmony with Greenwood's views. In 1888 Greenwood persuaded Edward Steinkopff (still in the Apollinaris business with George Smith, the ex-proprietor of the Pall Mall Gazette) to buy the St James's. But the new proprietor refused his editor the freedom he had so far enjoyed; and Greenwood retired suddenly and in anger within the year, to be succeeded by Sidney Low.[4]

St James's Gazette was one of the earliest supporters of the Imperialist movement, and between 1895 and 1899 was the chief advocate in the Press of resistance to the foreign bounties on sugar which disadvantaged British trade with the West Indies, thus giving an early impetus to the movement for Tariff Reform, and to Colonial or Imperial Preference.[9]

Hugh Chisholm joined the St James's Gazette as assistant editor in 1892 and was appointed editor in 1897.[10] In the same year the paper's proprietor Edward Steinkopff sold the massively successful Apollinaris business to the restaurateur and hotelier Frederick Gordon, receiving £1,500,000 as his share.[11][12]

During these years, Chisholm also contributed numerous articles on political, financial and literary subjects to the weekly journals and monthly reviews, becoming well known as a literary critic and Conservative publicist.

The paper appealed to and influenced a comparatively small circle of cultured readers, a "superior" function more and more difficult to reconcile with business considerations.[13] During the years immediately following 1892, when the Pall Mall Gazette again became Conservative, the competition between Conservative evening papers became acute, because The Globe and Evening Standard were also penny Conservative journals; and it was increasingly difficult to carry on the St James's on its old lines so as to secure a profit to the proprietor; by degrees modifications were made in the general character of the paper, with a view to its containing more news and less purely literary matter. But it retained its original shape, with sixteen (after 1897, twenty) small pages, a form which the Pall Mall had abandoned in 1892.[13]

A number of well-known writers had pieces or short stories published in the Gazette, including Thomas Hardy ('The Grave by the Handpost', Christmas number, November 1897);[14] Kenneth Grahame ("A Bohemian in Exile", the first of the Pagan Papers);[15] Andrew Lang's 'Old Friends', a series of parodic essays in the form of imagined letters between fictional characters;[16] P. G. Wodehouse (three articles from 1902–1903)[17] and Oscar Wilde ("Mr. Oscar Wilde on Mr. Oscar Wilde", 18 January 1895).[18]

Chisholm moved in 1899 to The Standard as chief leader-writer. His place on the St James's Gazette was taken in 1900 by the Irish barrister Ronald McNeill, (later Baron Cushendun).[n 2] Eric Parker (editor of The Field from 1911 until 1932) also worked there.[n 3]

One of the concerns in Britain around the turn of the century was immigration into the UK, prompted partially by the Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire[19] One of the most vociferous and outspoken anti-alien critics of the day was Major William Evans-Gordon, MP for Stepney, whose "restrictionist" rabble-rousing activities with the British Brothers' League led to the Aliens Act 1905. Evans-Gordon's 1903 book The Alien Immigrant[20] on the plight of Jewish and other (undesirable, in his view) immigrants was dedicated "To my friend, Edward Steinkopff", the owner of the St James's Gazette.[21] Steinkopff's only child, Mary Margaret Steinkopff, married Evans-Gordon's brother-in-law, Col. James Stewart-Mackenzie, 1st Baron Seaforth.[22][23]

St James's Budget

[edit]Starting on 3 July 1880, a weekly digest of the Gazette, including the main literary pieces and a summary of the week's news, was published as the St James's Budget. After 1893, it was turned into an independent illustrated weekly, edited from the same office by James Penderel-Brodhurst (later editor of The Guardian from 1905),[n 4] who had been on the editorial staff since 1888; and it continued to be published till 1899[13] or until 1911.[2]

Amalgamation

[edit]

C. Arthur Pearson (later described by Winston Churchill as "the champion hustler of the Tariff Reform League") had had a financial interest in the St James's Gazette for several years.[25] When the Tariff Reform battle started Pearson was the head of a syndicate which bought the morning Standard newspaper in 1904 for £300,000. With the acquisition went the London Evening Standard, which published every day a full list of Stock Exchange prices and was largely purchased on that account.[25]

Steinkopff sold the St James's Gazette (or a controlling interest in it) to Pearson in 1903, who amalgamated it with the Evening Standard on 13 March 1905;[8][25] the Gazette ceased publication thereafter.

Disambiguation

[edit]Neither the St James's Gazette nor the weekly St James's Budget are to be confused with the St James Magazine, a monthly magazine published in London by W. Kent & Co. in four series between April 1861 and January 1882.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Gibbs, director of the Bank of England was a Conservative merchant banker and a member of Antony Gibbs & Sons, a firm of merchant traders. His uncle's firm Gibbs Bright & Co. (of Bristol & Liverpool) had been previously involved in the West African slave trade to their Caribbean sugar plantations and acted as shipping agents for Brunel's SS Great Britain; the firm was latterly involved in the guano fertiliser trade with the Bolivian & Peruvian governments and later in the sodium nitrate trade (needed for munitions) in Chile.

- ^ Chisholm became editor-in-chief of the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica in 1903, with McNeill as assistant editor from 1906 to 1910

- ^ In his book Memory Looks Forward (1937) Parker recounted his memories of journalism beginning with the St James's Gazette under Ronald McNeill, afterwards Lord Cushendun. Source: J. B. Atkins, The Spectator, 29 October 1937, p. 34.

"Those who were journalists then will be made by the realism of the narrative to feel that they are living their lives again. The atmosphere and the methods described have almost passed away. Such papers as the St James's Gazette, the Globe and the Westminster Gazette were conducted by small thinking and writing staffs who, working anonymously, were ready to accept a collective credit or discredit. The well-known exaggeration that the influence of a paper is in inverse ratio to its circulation might have been invented for them – particularly for the Westminster Gazette." - ^ This was a London weekly paper published from 12 Jan. 1846 to 30 Nov. 1951,[24] sometimes contemporaneously called The London Guardian. Not to be confused with The Guardian (the Manchester Guardian before 1959), which moved publication to London in 1964.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Lee 1976, p. 165.

- ^ a b "St James's Budget". SUNCAT. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Christie's sale 6572, lot 203

- ^ a b c d Lee et al. 2012, p. 56.

- ^ C&D 1906, p. 399.

- ^ Andrews, Allen Robert Ernest (June 1968). The Forward Party: The Pall Gazette 1865–1889 (M.A. Thesis). Vancouver: University of British Columbia. pp. v, 26–44, 45–66. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ a b Jones 1992, p. 91.

- ^ a b Chapman-Huston 1936, p. 47.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 561.

- ^ Shattock 2000, p. 2934.

- ^ "London, 2 March 1906. Mr. Edward Steinkopff, who received £1,500,000 as his share of the Apollonaris business which he helped to found, died [in Feb. 1906] at Hayward's Heath." "Summary of World's Happenings". Poverty Bay Herald. Vol. 33, no. 10637. Gisborne, NZ. 12 April 1906. p. 4.

- ^ Frederick Gordon owned numerous hotels in London & the UK, and turned Bentley Priory into a hotel. Source: "Frederick Gordon, the world's greatest hotelier". Visit Stanmore. Stanmore Tourist Board.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 562.

- ^ Hardy, Thomas (2006). Brady, Kristin (ed.). The Withered Arm and Other Stories 1874–1888. Penguin UK. ISBN 0141938110.

- ^ Grahame, Kenneth (2016). Delphi Complete Works of Kenneth Grahame. Delphi Classics. p. 752. ISBN 978-1786560407.

- ^ Girvan, Ray (23 February 2012). "Andrew Lang: a sampler". Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ "Articles from St. James's Gazette (UK)". Madame Eulalie's Rare Plums. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Stokes, John (1989). In the Nineties. University of Chicago Press. pp. 164–5. ISBN 0226775380.

- ^ "Leaving the Homeland". Moving Here. The National Archives (UK). Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Evans-Gordon 1903.

- ^ Evans-Gordon 1903, p. v.

- ^ "Family: James Alexander Francis Humberston Stewart-Mackenzie, Baron Seaforth / Mary Margaret Steinkopff (F1944157960)". Red1st. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ "A remarkable man". Vancouver Daily World. 6 April 1906. p. 4. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ "The Guardian". Suncat. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Berry 1947, p. 36.

- ^ "The St James's magazine". SUNCAT. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Berry, William (1947). British Newspapers and their Proprietors. London, Toronto, Melbourne: Cassell & Co.

- Chapman-Huston, Desmond (1936). The lost historian: a memoir of Sir Sidney Low. London: J. Murray.

- "Mr Edward Steinkopff". The Chemist and Druggist: 399. 10 March 1906.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 565–2.

- Evans-Gordon, William (1903). The Alien immigrant. London: William Heinemann.

- Jones, Dorothy Richardson (1992). "King of Critics": George Saintsbury, 1845–1933, Critic, Journalist, Historian, Professor. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-10316-4.

- Lee, Alan J. (1976). The Origins of the Popular Press in England, 1855–1914. Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-87471-856-0.

- Lee, Sidney; Smith, George; Stephen, Leslie (2012). George Smith, a Memoir: With Some Pages of Autobiography. [1902]. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108047647.

- Shattock, Joanne, ed. (2000). The Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39100-9.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1912). "Greenwood, Frederick". Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1912). "Greenwood, Frederick". Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.