The Spirit of the Beehive

| The Spirit of the Beehive | |

|---|---|

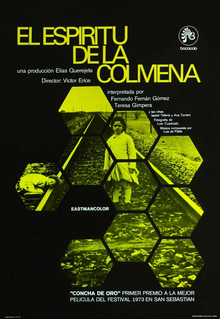

Spanish theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Víctor Erice |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Elías Querejeta |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Luis Cuadrado |

| Edited by | Pablo González del Amo |

| Music by | Luis de Pablo |

| Distributed by | Bocaccio Distribución |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | Spain |

| Language | Spanish |

The Spirit of the Beehive (Spanish: El espíritu de la colmena) is a 1973 Spanish drama film directed and co-written by Víctor Erice. The film was Erice's feature directorial debut and is considered a masterpiece of Spanish cinema.[1] The film, set in a small town in post-Civil War Spain, focuses on a young girl named Ana. It traces family and school dynamics, her fascination with the 1931 American horror film Frankenstein, her exploration of a haunted home and landscape, making subtle references towards the dark, contentious politics of the time.

Many have noted the symbolism present throughout the film, used both as an artistic device and as a way to avoid censorship under the repressive Franco regime. While censors were alarmed by some of the film's suggestive content about the authoritarian government, they allowed it to be released in Spain based on its success abroad, under the assumption that most of the public would have no real interest in seeing "a slow-paced, thinly-plotted and 'arty' picture."[2]

The film has been called a "bewitching portrait of a child's haunted inner life".[3]

Plot

[edit]Six-year-old Ana is a shy girl who lives in the manor house in an isolated Spanish village on the Castilian plateau with her parents Fernando and Teresa and her older sister, Isabel. The year is 1940, and the civil war has just ended with the Francoist victory over the Republican forces. Her aging father spends most of his time absorbed in tending to and writing about his beehives; her much younger mother is caught up in daydreams about a distant lover, to whom she writes letters. Ana's closest companion is Isabel, who loves her but cannot resist playing on her little sister's gullibility.

A mobile cinema brings Frankenstein to the village and the two sisters go to see it. The film makes a deep impression on Ana, who is especially riveted by the scene where the monster plays benignly with a little girl, then accidentally kills her. She asks her sister: "Why did he kill the girl, and why did they kill him after that?" Isabel tells her that the monster did not kill the girl and is not really dead; she says that everything in films is fake. Isabel says the monster is like a spirit, and Ana can talk to him if she closes her eyes and calls him.

Ana's fascination with the story increases when Isabel takes her to a desolate sheepfold, which she claims is the monster's house. Ana returns alone several times to look for him and eventually discovers a wounded republican soldier hiding in the sheepfold. Instead of running away, she feeds him and even brings him her father's coat and watch. One night the Francoist police come and find the republican soldier and shoot him. The police soon connect Ana's father with the fugitive and assume he stole the items from him. The father discovers which of the daughters had helped the fugitive by noticing Ana's reaction when he produces the pocket watch. When Ana next goes to visit the soldier, she finds him gone, with blood stains still on the ground. Her father confronts her, and she runs away.

Ana's family and the other villagers search for her all night, mirroring a scene from Frankenstein. While she kneels next to a lake, she sees Frankenstein's monster approaching from the forest, kneeling beside her. The next day, they find Ana physically unharmed. The doctor assures her mother that she will gradually recover from her unspecified "trauma", but Ana instead withdraws from her family, preferring to stand alone by the window and silently call to the spirit, just as Isabel told her.

Cast

[edit]- Fernando Fernán Gómez as Fernando

- Teresa Gimpera as Teresa

- Ana Torrent as Ana

- Isabel Tellería as Isabel

- Ketty de la Cámara as Milagros, the maid

- Estanis González as Civil Guard

- José Villasante as the Frankenstein Monster

- Juan Margallo as the fugitive

- Laly Soldevila as Doña Lucía, the teacher

- Miguel Picazo as Doctor

Historical context

[edit]Francisco Franco came to power in Spain in 1939, after a bloody civil war that overthrew a leftist government. The war split families and left a society divided and intimidated into silence in the years following the civil war. The film was made in 1973, when the Francoist State was not as severe as it had been at the beginning; however, it was still not possible to be openly critical of the Francoist State. Artists in all media in Spain had already managed to slip material critical of Francoist Spain past the censor. Most notable is the director Luis Buñuel, who shot Viridiana there in 1962. By making films rich in symbolism and subtlety, a message could be embodied in a film that would be accepted or missed by the censor's office.[4]

Symbolism

[edit]The film is rife with symbolism and the disintegration of the family's emotional life can be seen as symbolic of the emotional disintegration of the Spanish nation during the civil war.[4][5][6]

The beehive itself has symbolism not only for the audience, but also for one of the characters: Fernando the father. And the beehive symbolizes the same thing for both parties: “the inhumanity of fascist Spain.”[7]

The barren empty landscapes around the sheepfold have been seen as representing Spain's isolation during the beginning years of the Francoist State.[6]

In the film, Fernando describes in writing his revulsion at the mindless activity of the beehive. This is possibly an allusion to human society under Francoism: ordered, organised, but devoid of any imagination.[4][5][6] The beehive theme is carried into the manor house which has hexagonal panes to its leaded windows and is drenched in a honey-colored light.[4][6][8]

The symbolism of this film does not just cover political topics; it also covers aspects of childhood, such as fears, anxieties, and imagination.[9]

Ana represents the innocent young generation of Spain around 1940, while her sister Isabel's deceitful advice symbolizes the Nationals (the Nationalist faction soldiers led by Franco, and their supporters), accused of being obsessed with money and power.[6]

Even the film's setting in history has symbolism of its own. 1940 was a year that Erice and other Spaniards of his generation saw as the start of Franco's rule over Spain.[10]

Production

[edit]The film's producer, Elías Querejeta, worried that the film would not reach completion.[11]

In a prior version of the story, originally set in the period of the 1970s, an aged version of Ana's father is terminally ill, and she returns to her village to reunite with him. Thinking that this version would “tidy up the drama, emphasizing soap opera over childish magic,” Erice changed the story.[2]

The location used was the village of Hoyuelos, Segovia, Castilla y León, Spain.[12]

The four main characters each have a first name identical to that of the actor playing them. This is because Ana, at her young age of seven at the time of filming, was confused by the on- and off-screen naming. Erice simply changed the script to adopt the actors' names for the characters.[13]

Víctor Erice wrote of his choice of title:

"The title really is not mine. It is taken from a book, in my opinion the most beautiful thing ever written about the life of bees, written by the great poet and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck. In that work, Maeterlinck uses the expression 'The Spirit of the Beehive' to name the powerful, enigmatic and paradoxical force that the bees seem to obey, and that the reason of man has never come to understand."[8]

The film's cinematographer, Luis Cuadrado, was going blind during filming.[14]

Critical reception

[edit]According to the DVD supplement "Footprints of a Spirit" in the Criterion Collection's presentation of The Spirit of the Beehive, when the film was awarded first prize at the prestigious San Sebastian Film Festival, there were boos of derision and some people stomped their feet in protest. The film's producer said many in the audience offered him their condolences after the first screening in late 1973.

Years later, when the film was re-released in the United States in early 2007, A. O. Scott, film critic for The New York Times, lauded the direction of the drama: "The story that emerges from [Erice's] lovely, lovingly considered images is at once lucid and enigmatic, poised between adult longing and childlike eagerness, sorrowful knowledge and startled innocence."[15]

Film critic Dan Callahan praised the film's cinematography, story, direction and acting. He wrote, "Every magic hour, light-drenched image in Victor Erice's The Spirit of the Beehive is filled with mysterious dread....There's something voluptuous about the cinematography, and this suits the sense of emerging sexuality in the girls, especially in the scene where Isabel speculatively paints her lips with blood from her own finger...[and] Torrent, with her severe, beautiful little face, provides an eerily unflappable presence to center the film. The one time she smiles, it's like a small miracle, a glimpse of grace amid the uneasiness of black cats, hurtling black trains, devouring fire and poisonous mushrooms. These signs of dismay haunt the movie."[16]

Tom Dawson of the BBC wrote of how the film handled using its lead child actors to portray children's point of view, praising the young actresses Ana Torrent and Isabel Tellería. “Expressively played by its two young leads, it's a work which memorably captures a child's perspective on the mysteries of everyday life.”[9]

A Variety review at the time of the film's release applauds the film's actors, Ana Torrent and Fernando Fernán Gómez in particular, and points to the simplicity of the scenes in the film as a source of its charm.[17] Critic John Simon wrote "For total incompetence, however, there is nothing like The Spirit of the Beehive".[18]

In 2007, Kim Newman of Empire praised Ana Torrent for her performance, saying she "carries the film with a remarkable, honest performance — perhaps the best work ever done by a child actor." Newman refers to the emotion carried in Ana's and the film's final line, "Yo soy Ana/It's me Ana." Newman also commended the film's lack of explanation for the events happening on screen, "or, indeed, precisely what is going on in Ana's family, the village or the country."[2]

In 1999, Derek Malcolm of The Guardian wrote "It is one of the most beautiful and arresting films ever made in Spain, or anywhere in the past 25 years or so." He describes the film as "an almost perfect summation of childhood imaginings," and also points out that the effect of the Franco regime on Spain is a topic covered by the film. Malcolm also praised the work of cinematographer Luís Cuadrado calling it "brilliant," mentioning the "atmospherically muted colors."[11]

In a 1977 review, Gary Arnold of The Washington Post gave a more critical review of Erice's film. He writes that Erice has a problematic belief in using "long, ponderous, static takes," and goes on to say that Erice "overstocked" this film with those kinds of takes.[19]

By 20 November 2012 the film had been entered into Roger Ebert's "Great Movies" selection.[20]

As of 2022, it is the only film by a Spanish or Latin American director to appear on Sight and Sound's list of the 100 greatest films of all time.[21]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 96% approval rating based on 26 reviews, with an average rating of 9.00/10. The site's critics consensus reads: "El Espíritu de la Colmena uses a classic horror story's legacy as the thread for a singularly absorbing childhood fable woven with uncommon grace."[22] At Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 87 out of 100, based on 4 critics, indicating "universal acclaim”.[23]

The Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa cited this movie as one of his 100 favorite films.[24]

Legacy

[edit]The Spirit of the Beehive would become one of the most influential genre movies in Spanish history and inspire future filmmakers. Guillermo del Toro's films The Devil's Backbone (2001) and Pan's Labyrinth (2006) particularly resort to the idea that children believe and act according to their beliefs about imaginary worlds around this period of Spain's history.[2] The movie's dream-logic visuals and metaphorical storytelling also laid the groundwork and shaped the vision of Issa López's 2017 film Tigers Are Not Afraid. Erice's work emphasizes the importance of imagination, art, and our own ability to get lost in the fiction we gravitate towards. Even if that fiction happens to be full of monsters.[25]

Accolades

[edit]- Nominated

- Chicago International Film Festival: Gold Hugo, Best Feature, Víctor Erice; 1973[26]

- Wins

- San Sebastián International Film Festival: Golden Shell, Víctor Erice; 1973.[27]

- Cinema Writers Circle Awards, Spain: CEC Award; Best Film; Best Actor, Fernando Fernán Gómez; Best Director, Víctor Erice; 1974.[28]

- Fotogramas de Plata, Madrid, Spain: Best Spanish Movie Performer, Ana Torrent; 1974.[29]

- Association of Latin Entertainment Critics: Premios ACE, Cinema, Best Actress, Ana Torrent; Cinema, Best Director, Víctor Erice; 1977.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Curran, Daniel, ed. Foreign Films, film review and analysis of The Spirit of the Beehive, pp. 161-2, 1989. Evanston, Illinois: Cinebooks. ISBN 0-933997-22-1.

- ^ a b c d "Empire Essay: The Spirit Of The Beehive". Empire. 2007-02-12. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ The Criterion Collection. Accessed 2010

- ^ a b c d Hagopian, Kevin Jack (8 April 2009). "FILM NOTES -The Spirit of the Beehive". New York State Writers' Institute. University of Albany. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ a b Wilson, Kevin (25 August 2008). "The Spirit of the Beehive (1973, Spain, Victor Erice)". thirtyframesasecond. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Kohrs, Deanna. "Cinergía Movie File: The Spirit of the Beehive (El espíritu de la colmena)". Cinergía. Pennsylvania State University. pp. Section 3: Media analysis. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Jeffries, Stuart (2010-10-20). "The Spirit of the Beehive: No 25 best arthouse film of all time". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ a b "The Spirit of the Beehive, a film by Victor Erice". El Parnasio (in Spanish). Spain. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ a b "BBC - Films - Review - The Spirit of the Beehive (El Espíritu de la Colmena)". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ "Erice's 'Beehive' Buzzing With Satire". Los Angeles Times. 1994-06-02. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ a b Malcolm, Derek (1999-09-16). "Victor Erice: The Spirit of the Beehive". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ "Filming locations for El espíritu de la colmena". IMDB. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Crítica de El espíritu de la comena, una película de Víctor Erice con Ana Torrent y Fernando Fernán-Gómez". www.el-parnasillo.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2016-11-27.

- ^ "Luís Cuadrado", Great Cinematographers, Internet Encyclopedia of Cinematographers.

- ^ Scott, A. O. The New York Times, film review, January 27, 2006. Last accessed: December 18, 2007.

- ^ Callahan, Dan Archived 2007-12-13 at the Wayback Machine. Slant, film review, 2006. Last accessed: December 23, 2007.

- ^ "El Espiritu de la Colmena". Variety. 1973-01-01. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ Simon, John (1983). John Simon: Something to Declare Twelve Years Of Films From Abroad. Clarkson N. Potter Inc. p. 306.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (1977-08-10). "A Solemn 'Beehive'". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (20 November 2012). "Everything in the movies is fake". Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- ^ Fernández-Santos, Elsa (11 December 2022). "'Sight & Sound' poll rekindles debate about the greatest films of all time". El País. Madrid. Retrieved 25 December 2024.

- ^ "The Spirit of the Beehive (El Espíritu de la Colmena)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "The Spirit of the Beehive". Metacritic. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ Thomas-Mason, Lee (12 January 2021). "From Stanley Kubrick to Martin Scorsese: Akira Kurosawa once named his top 100 favourite films of all time". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Alan Kelly (2 May 2024). "'The Spirit Of The Beehive' And Its Monstrous Legacy". Dread Central. Retrieved 25 December 2024.

- ^ "Chicago International Film Festival (1973)". IMDb. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ^ "72nd San Sebastian Festival (1973). El espíritu de la colmena / The Spirit of the Beehive". San Sebastián International Film Festival. Retrieved 2024-12-25.

- ^ "Cinema Writers Circle Awards, Spain (1974)". IMDb. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Fotogramas de Plata (1974)". IMDb. Retrieved 2024-12-25.

- ^ "Premios ACE (1977)". IMDb. Retrieved 2024-12-25.

Bibliography

[edit]- Curran, Daniel, ed. Foreign Films, pp. 161–2, 1989. Evanston, Illinois: Cinebooks. ISBN 0-933997-22-1.

External links

[edit]- 1973 films

- 1973 directorial debut films

- 1973 drama films

- 1970s fantasy drama films

- 1970s Spanish-language films

- Spanish fantasy drama films

- Films about father–daughter relationships

- Films about sisters

- Films directed by Víctor Erice

- Films produced by Elías Querejeta

- Films scored by Luis de Pablo

- Films set in 1940

- Films set in Spain

- Films shot in the province of Segovia

- 1970s Spanish films

- Spanish coming-of-age drama films

- 1970s coming-of-age drama films