Incantation

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

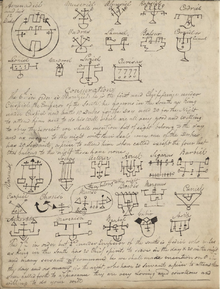

An incantation, a spell, a charm, an enchantment, or a bewitchery, is a magical formula intended to trigger a magical effect on a person or objects. The formula can be spoken, sung, or chanted. An incantation can also be performed during ceremonial rituals or prayers. In the world of magic, wizards, witches, and fairies are common performers of incantations in culture and folklore.[1]

In medieval literature, folklore, fairy tales, and modern fantasy fiction, enchantments are charms or spells. This has led to the terms "enchanter" and "enchantress" for those who use enchantments.[2] The English language borrowed the term "incantation" from Old French in the late 14th century; the corresponding Old English term was gealdor or galdor, "song, spell", cognate to ON galdr. The weakened sense "delight" (compare the same development of "charm") is modern, first attested in 1593 (OED).

Words of incantation are often spoken with inflection and emphasis on the words being said. The tone and rhyme of how the words are spoken and the placement of words used in the formula may differ depending on the desired outcome of the magical effect.[3]

Surviving written records of historical magic spells were largely obliterated in many cultures by the success of the major monotheistic religions (Islam, Judaism, and Christianity), which label some magical activity as immoral or associated with evil.[4][unreliable source?]

Etymology

[edit]

The Latin incantare, which means "to consecrate with spells, to charm, to bewitch, to ensorcel", forms the basis of the word "enchant", with deep linguistic roots going back to the Proto-Indo-European kan- prefix. So it can be said that an enchanter or enchantress casts magic spells, or utters incantations.

The words that are similar to incantations such as enchantment, charms and spells are the effects of reciting an incantation. To be enchanted is to be under the influence of an enchantment, usually thought to be caused by charms or spells.

Magic words

[edit]

Magic words or words of power are words which have a specific, and sometimes unintended, effect. They are often nonsense phrases used in fantasy fiction or by stage prestidigitators. Frequently such words are presented as being part of a divine, adamic, or other secret or empowered language. Certain comic book heroes use magic words to activate their powers.

Examples of traditional magic words include Abracadabra, Alakazam, Hocus Pocus, Open Sesame and Sim Sala Bim.

In Babylonian, incantations can be used in rituals to burn images of one's own enemies. An example would be found in the series of Mesopotamian incantations of Šurpu and Maqlû. In the Orient, the charming of snakes have been used in incantations of the past and still used today. A person using an incantation would entice the snake out of its hiding place in order to get rid of them.[1]

Udug-hul

[edit]In Mesopotamian mythology, Udug Hul incantations are used to exorcise demons (evil Udug) who bring misfortune or illnesses, such as mental illness or anxiety. These demons can create horrible events such as divorce, loss of property, or other catastrophes.[5]

In folklore and fiction

[edit]

In traditional fairy tales magical formulas are sometimes attached to an object.[citation needed] When the incantation is uttered, it helps transform the object. In such stories, incantations are attached to a magic wand used by wizards, witches and fairy godmothers. One example is the spell that Cinderella's Fairy Godmother used to turn a pumpkin into a coach, "Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo", a nonsense rhyme which echoes more serious historical incantations.[6]

Modern uses and interpretations

[edit]The performance of magic almost always involves the use of language. Whether spoken out loud or unspoken, words are frequently used to access or guide magical power. In The Magical Power of Words (1968), S. J. Tambiah argues that the connection between language and magic is due to a belief in the inherent ability of words to influence the universe. Bronisław Malinowski, in Coral Gardens and their Magic (1935), suggests that this belief is an extension of man's basic use of language to describe his surroundings, in which "the knowledge of the right words, appropriate phrases and the more highly developed forms of speech, gives man a power over and above his own limited field of personal action."[7]: 235 Magical speech is therefore a ritual act and is of equal or even greater importance to the performance of magic than non-verbal acts.[8]: 175–176

Not all speech is considered magical. Only certain words and phrases or words spoken in a specific context are considered to have magical power.[8]: 176 Magical language, according to C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards's (1923) categories of speech, is distinct from scientific language because it is emotive and it converts words into symbols for emotions; whereas in scientific language words are tied to specific meanings and refer to an objective external reality.[8]: 188 Magical language is therefore particularly adept at constructing metaphors that establish symbols and link magical rituals to the world.[8]: 189

Malinowski argues that "the language of magic is sacred, set and used for an entirely different purpose to that of ordinary life."[7]: 213 The two forms of language are differentiated through word choice, grammar, style, or by the use of specific phrases or forms: prayers, spells, songs, blessings, or chants, for example. Sacred modes of language often employ archaic words and forms in an attempt to invoke the purity or "truth" of a religious or a cultural "golden age". The use of Hebrew in Judaism is an example.[8]: 182

Another potential source of the power of words is their secrecy and exclusivity. Much sacred language is differentiated enough from common language that it is incomprehensible to the majority of the population and it can only be used and interpreted by specialized practitioners (magicians, priests, shamans, or Imams).[7]: 228 [8]: 178 In this respect, Tambiah argues that magical languages violate the primary function of language: communication.[8]: 179 Yet adherents of magic are still able to use and to value the magical function of words by believing in the inherent power of the words themselves and in the meaning that they must provide for those who do understand them. This leads Tambiah to conclude that "the remarkable disjunction between sacred and profane language which exists as a general fact is not necessarily linked to the need to embody sacred words in an exclusive language."[8]: 182

Examples of charms

[edit]

- The Anglo-Saxon metrical charms

- Thoth's Tarot Card deck by Aleister Crowley

- The Carmina Gadelica, a collection of Gaelic oral poetry, much of it charms

- The Atharvaveda, a collection of charms, and the Rigveda, a collection of hymns or incantations

- Hittite ritual texts

- The Greek Magical Papyri

- Maqlû, Akkadian incantation text

- The Merseburg charms, two medieval magic spells, charms written in Old High German

- Cyprianus, a generic term for a book of Scandinavian folk spells

- Pow-Wows; or, Long Lost Friend

- Babylonian incantations[9]

- Mesopotamian incantations were composed to counter anything from witchcraft (Maqlû) to field pests (Zu-buru-dabbeda).

See also

[edit]- Carmen, a term for an Ancient Roman incantation

- Curse (disambiguation)

- Dharani, common term for Mahayana Buddhist mantras

- Finnic incantations

- Hex (disambiguation)

- Incantations in the Harry Potter series

- Incantation bowl, an ancient Middle Eastern protective magical tool

- Jinx (disambiguation)

- Kotodama, the Japanese belief in the power of words and names

- Lorica, Irish protective prayer

- Mantra, a sacred sound, word, or phrase, often repeated multiple times, in meditation

- Paritta, common term for Theravada Buddhist mantras

- Spell (ritual)

- Yajna, Hindu sacrificial offering

- Zagovory, East Slavic spells

References

[edit]- ^ a b Cushman, Stephen (2012). Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics : Fourth Edition. Princeton, ProQuest Ebook Central: Princeton University Press. p. 681.

- ^ Conley, Craig (2008). Magic Words, A Dictionary. San Francisco: Weiser Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-57863-434-7.

- ^ Conley, Craig (2008). Magic Words:a dictionary. San Francisco: Weiser Books. pp. 23–27. ISBN 978-1-57863-434-7.

- ^ Davies, Owen (8 April 2009). "The top 10 grimoires". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ Markham, Geller (2015). Healing Magic and Evil Demons : Canonical Udug-Hul Incantations. De Gruyter, Inc. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9781614515326.

- ^ Garry, Jane (2005). Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature. Armonk: M.E. Sharp. p. 162. ISBN 0-7656-1260-7.

- ^ a b c Malinowski, Bronislaw (2013). Coral Gardens and Their Magic: A Study of the Methods of Tilling the Soil and of Agricultural Rites in the Trobriand Islands. Hoboken, New Jersey: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1136417733.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tambiah, S. J. (June 1968). "The Magical Power of Words". Man. 3 (2): 175–208. doi:10.2307/2798500. JSTOR 2798500.

- ^ "The Recordings: BAPLAR: SOAS". speechisfire.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

External links

[edit] Media related to Incantations at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Incantations at Wikimedia Commons