Mirror writing

Mirror writing is formed by writing in the direction that is the reverse of the natural way for a given language, such that the result is the mirror image of normal writing: it appears normal when reflected in a mirror. It is sometimes used as an extremely primitive form of cipher. A common modern usage of mirror writing can be found on the front of ambulances, where the word "AMBULANCE" is often written in very large mirrored text, so that drivers see the word the right way around in their rear-view mirror. It is also on fire engines and police cars too.

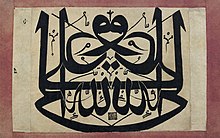

Some people are able to produce handwritten mirrored text. Notably, Leonardo da Vinci wrote most of his personal notes in this way.[1] Mirror writing calligraphy was popular in the Ottoman Empire, where it often carried mystical associations.

Ability to write mirrored text

[edit]

An informal Australian newspaper experiment identified 10 true mirror-writers in a readership of 65,000.[2] A higher proportion of left-handed people are better mirror writers than right-handed people, perhaps because it is more natural for a left-hander to write from right to left.[3] 15% of left-handed people have the language centres in both halves of their brain.[citation needed] The cerebral cortex and motor homunculus are affected by this, causing the person to be able to read and write backwards quite naturally.

In an experiment conducted by the Department of Neurosurgery at Hokkaido University School of Medicine in Sapporo, Japan, scientists proposed that the origin of mirror writing comes from damage caused through brain trauma or neurological diseases, such as an essential tremor, Parkinson's disease,[4] or spino-cerebellar degeneration. This hypothesis was proposed because these conditions affect a "neural mechanism that controls the higher cerebral function of writing via the thalamus."[5] Another study by the same university discovered that damage was not the only cause. The scientists observed that normal children exhibited signs of mirror writing while learning to write, thus concluding that currently there is no exact method for finding the true origin of mirror writing.

Notable examples

[edit]

Leonardo da Vinci wrote most of his personal notes in mirror writing, only using standard writing if he intended his texts to be read by others. The purpose of this practice by Leonardo remains unknown, though several possible reasons have been suggested. For example, writing left handed from left to right would have been messy because the ink just put down would smudge as his hand moved across it. Writing in reverse would prevent such smudging. An alternative theory is that the process of rotating the linguistic object in memory before setting it to paper, and rotating it before reading it back, was a method of reinforcement learning. From this theory, it follows the use of boustrophedonic writing, especially in public codes, may be to render better recall of the text in the reader.[citation needed]

Matteo Zaccolini may have written his original four volume treatise on optics, color, and perspective in the early 17th century in mirror script.[citation needed][further explanation needed]

Pictorial texts also known as calligrams arranged in mirror symmetry were popular in the Ottoman Empire during the 18th and 19th centuries among the Bektashi order, where it often carried mystical associations.[6] The origins of this mirror writing tradition may date to the pre-Islamic period in rock inscriptions of the western Arabian peninsula.[6] A recent study that has revealed the oldest examples of mirror writing in Greek [clarification needed] traces the early appearance of mirror inscriptions to Late Antiquity, specifically to Syria-Palestine, Egypt, and Constantinople.[citation needed] In Islamic art, mirror calligraphy is known as muthanna or musanna.[7]

Peep show images shown in a zograscope have headers in mirror writing.

See also

[edit]- Ahriman – Middle Persian word traditionally written upside down

- Ambigram – Symmetrical calligraphic or typographic visual pun

- Faux Cyrillic – Several Cyrillic alphabet characters closely resemble mirrored Latin characters

References

[edit]- ^ Jones, Roger (1 June 2012). "Leonardo da Vinci: anatomist". British Journal of General Practice. 62 (599): 319. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X649241. ISSN 0960-1643. PMC 3361109. PMID 22687222.

- ^ Wednesday, 2 June 2004 Anna SallehABC (2 June 2004). "Mirror writing: my genes made me do it". www.abc.net.au.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Schott, G. D. (2004). "Mirror Writing, Left-handedness, and Leftward Scripts". Archives of Neurology. 61 (12): 1849–51. doi:10.1001/archneur.61.12.1849. PMID 15596604.

- ^ Shinohara, Mayumi; Yokoi, Kayoko; Hirayama, Kazumi; Kanno, Shigenori; Hosokai, Yoshiyuki; Nishio, Yoshiyuki; Ishioka, Toshiyuki; Otsuki, Mika; Takeda, Atsushi; Baba, Toru; Aoki, Masashi; Hasegawa, Takafumi; Kikuchi, Akio; Narita, Wataru; Mori, Etsuro (14 December 2022). "Mirror writing and cortical hypometabolism in Parkinson's disease". PLOS ONE. 17 (12): e0279007. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1779007S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0279007. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9750002. PMID 36516196.

- ^ Tashiro K, Matsumoto A, Hamada T, Moriwaka F (1987). "The aetiology of mirror writing: a new hypothesis". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 50 (12): 1572–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.50.12.1572. PMC 1032596. PMID 3437291.

- ^ a b Library of Congress image bibliographic data.[1] Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ Esra Akın-Kıvanç, Muthanna / Mirror Writing in Islamic Calligraphy: History, Theory, and Aesthetic (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020)

External links

[edit] Media related to Mirror writings at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mirror writings at Wikimedia Commons- Mirror writing: neurological reflections on an unusual phenomenon

- Jay A. Gottfried, Kruba Sundar, Feyza Sancar, Anjan Chatterjee. "Acquired mirror writing and reading: evidence for reflected graphemic representations" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)