Where no man has gone before

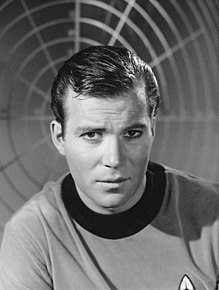

"Where no man has gone before" is a phrase made popular through its use in the title sequence of the original 1966–1969 Star Trek science fiction television series, describing the mission of the starship Enterprise. The complete introductory speech, spoken by William Shatner as Captain James T. Kirk at the beginning of each episode, is:

Space: the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Its five-year mission: to explore strange new worlds; to seek out new life and new civilizations; to boldly go where no man has gone before!

This introduction began every episode of the series except the two pilot episodes: "The Cage" (which preceded Shatner's involvement) and "Where No Man Has Gone Before". This introduction was used for the beginning of each episode of the show Star Trek: The Next Generation, but with the phrase "five-year mission" changed to a more open-ended "continuing mission", and the final phrase changed to the gender- and species-neutral "where no one has gone before". The complete introduction, spoken by Patrick Stewart as Captain Jean-Luc Picard, is:

Space: the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Its continuing mission: to explore strange new worlds; to seek out new life and new civilizations; to boldly go where no one has gone before!

The series produced after The Next Generation would not use any form of introductory speeches, until the prequel series Star Trek: Strange New Worlds. The introduction, spoken by Anson Mount as Captain Christopher Pike, Kirk’s predecessor, leads the title sequence of every episode and combines Kirk’s version of the speech with the neutral final phrase.[1]

Origin

[edit]A variation of the phrase "where no man has gone before", "by oceans where none had ventured", was first used by the noted Portuguese poet Luís de Camões in his epic poem The Lusiads, published in 1572. The poem celebrates the Portuguese nation and its discovery of the sea route to India by Vasco da Gama.[2]

Blogger Dwayne A. Day says the quotation was taken from Introduction to Outer Space, a White House booklet published in 1958 to garner support for a national space program in the wake of the Sputnik flight.[3] It read on page 1:

The first of these factors is the compelling urge of man to explore and to discover, the thrust of curiosity that leads men to try to go where no one has gone before. Most of the surface of the earth has now been explored and men now turn to the exploration of outer space as their next objective.[4]

Following an early expedition to Newfoundland, Captain James Cook declared that he intended to go not only "... farther than any man has been before me, but as far as I think it is possible for a man to go"[5] (emphasis added). Cook's most famous ship, the Endeavour, lent its name to the last-produced Space Shuttle, much as the Star Trek starship Enterprise lent its name to the Shuttle program's test craft.

Similar expressions have been used in literature before 1958. For example, H. P. Lovecraft's novella The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, written in 1927 and published in 1943, includes this passage:

At length, sick with longing for those glittering sunset streets and cryptical hill lanes among ancient tiled roofs, nor able sleeping or waking to drive them from his mind, Carter resolved to go with bold entreaty whither no man had gone before, and dare the icy deserts through the dark to where unknown Kadath, veiled in cloud and crowned with unimagined stars, holds secret and nocturnal the onyx castle of the Great Ones.[6]

The phrase was first introduced into Star Trek by Samuel Peeples, who is attributed with suggesting it be used as an episode name.[7][8] The episode became "Where No Man Has Gone Before", the second pilot of Star Trek. The phrase itself was subsequently worked into the show's opening narration, which was written in August 1966, after several episodes had been filmed, and shortly before the series was due to debut. It is the result of the combined input of several people, including Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry and producers John D. F. Black and Bob Justman.[9] One of the earliest drafts is as follows:

This is the adventure of the United Space Ship Enterprise. Assigned a five year galaxy patrol, the bold crew of the giant starship explores the excitement of strange new worlds, uncharted civilizations, and exotic people. These are its voyages and its adventures...

Under their influence, the above narrative quote went through several revisions before being selected for use in the TV series.[10]

In-universe, the sentence was attributed in the Star Trek: Enterprise pilot episode "Broken Bow" to warp drive inventor Dr. Zefram Cochrane in a recorded speech during the dedication of the facility devoted to designing the first engine capable of reaching Warp 5 — thus making interstellar exploration practical for humans — in the year 2119, some thirty-two years before the 2151 launch of the first vessel powered by such an engine, the Enterprise (NX-01):

On this site, a powerful engine will be built. An engine that will someday help us to travel a hundred times faster than we can today. Imagine it – thousands of inhabited planets at our fingertips... and we'll be able to explore those strange new worlds, and seek out new life and new civilizations. This engine will let us go boldly... where no man has gone before.

Other uses

[edit]Leonard Nimoy as Spock delivered a slightly altered version of the full monologue at the end of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, separate from the version used on The Next Generation. In this version, the monologue describes the crew's mission as a search not just for new life, but for "new lifeforms". The first statement, "These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise" is also augmented as "These are the continuing voyages of the starship Enterprise"; the ship's "five-year mission" is consequently changed to the crew's "ongoing mission". The complete monologue is:

Space: the final frontier. These are the continuing voyages of the starship Enterprise. Their ongoing mission: to explore strange new worlds; to seek out new lifeforms and new civilizations; to boldly go where no man has gone before!

The final phrase is referenced in-universe as Kirk narrates his final captain's log at the conclusion of Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country; he notes that the next crew of the Enterprise will continue "boldly going where no man... where no one... has gone before", a change prompted by criticism from aliens earlier in the film of the crew's human-centrism. The neutral version of the final phrase had already been in use in the introductory speech for The Next Generation, which debuted four years earlier.

The full monologue was once again spoken at the end of the Star Trek: Enterprise series finale, "These Are the Voyages...," by the captains of the three main starships (NCC-1701-D, NCC-1701, and NX-01) to bear the name Enterprise; Patrick Stewart spoke the first two sentences, William Shatner the third and fourth, and Scott Bakula — as Captain Jonathan Archer — the final sentence. This version combines the phrases "Its continuing mission" (spoken by Stewart) and "where no man has gone before" (spoken by Bakula) into the same speech.

Versions of the full monologue were used at the end of each film in the Star Trek reboot trilogy; all use the more neutral final phrase. In the 2009 film Star Trek, the monologue is spoken by Leonard Nimoy and uses his version from The Wrath of Khan with the word "continuing" removed. The monologue is used in-universe as part of a speech delivered by Chris Pine's Kirk at the Enterprise's re-dedication ceremony in Star Trek Into Darkness; the version spoken by William Shatner's Kirk is used, altered with "Her five-year mission". Star Trek Beyond uses the same version from The Next Generation, spoken by Kirk, Spock, Scotty, Bones, Sulu, Chekov, and Uhura.

Outside Star Trek

[edit]The phrase has also gained popularity outside Star Trek. In 1989, NASA used the phrase to title its retrospective of Project Apollo: Where No Man Has Gone Before: A History of Apollo Lunar Exploration Missions.[11]

The phrase has become a snowclone, a rhetorical device and type of word play in which one word within it is replaced while maintaining the overall structure. For example, a 2002 episode of Futurama that dealt with a character's devotion to Star Trek is named "Where No Fan Has Gone Before", a level in the video game Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Turtles in Time is called "Starbase: Where No Turtle Has Gone Before".[12] The Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti became the first barista in space on the International Space Station, tweeting "To Boldly Brew..." in May 2015; she wore Star Trek garb for the occasion.[13]

The phrase was parodied on the retail box of the 1987 computer game Space Quest: The Sarien Encounter, which read "His mission: to scrub dirty decks...to replace burned-out lightbulbs...TO BOLDLY GO WHERE NO MAN HAS SWEPT THE FLOOR!" (emphasis original).[14] In 1992, Apple's Star Trek project, a port of their Mac OS 7 operating system to Intel x86 processors, was referred to as "the OS that boldly goes where everyone else has been".[citation needed] In the sci-fi show Babylon 5, the character Susan Ivanova implies that a woman is promiscuous by telling Captain John Sheridan, "Good luck, Captain. I think you're about to go where... everyone has gone before."[15]

The split infinitive "to boldly go" has also been the subject of jokes regarding its grammatical correctness. British humorist and science-fiction author Douglas Adams describes, in his series The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, the long-lost heroic age of the Galactic Empire, when bold adventurers dared "to boldly split infinitives that no man had split before".[16] In the 1995 book The Physics of Star Trek, Lawrence M. Krauss begins a list of Star Trek's ten worst errors by quoting one of his colleagues who considers that their greatest mistake is "to split an infinitive every damn time".[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Video on YouTube

- ^ Puchner, Martin (2023). Culture: The Story of Us, from Cave Art to K-Pop (Kindle ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 281. ISBN 978-0393867992.

- ^ Dwayne A. Day,"Boldly going: Star Trek and spaceflight", in The Space Review, 28 November 2005. Retrieved 15 August 2006.

- ^ The President's Science Advisory Committee (26 March 1958). "Introduction to Outer Space". Washington, D.C.: The White House. p. 1. Archived from the original on 3 May 2006. Retrieved 15 August 2006 – via U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Williams, Glyn (1 August 2002). "Captain Cook: Explorer, Navigator and Pioneer". Empire and Seapower. BBC. Retrieved 25 January 2007.

- ^ Lovecraft, H. P. (1943). Beyond the Wall of Sleep. Arkham House. Available in Wikisource.

- ^ David Alexander (1994). Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry. ROC. ISBN 9780451454188.

- ^ Whitfield, Stephen E & Roddenberry, Gene (1968). The Making of Star Trek. Ballatine Books.

- ^ Blair Shewchuk. "Words: Woe and Wonder, To Boldly Split Infinitives". CBC News Online.

- ^ "Gene Roddenberry Star Trek Television Series Collection". UCLA Library. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ W. David Compton, "Where No Man Has Gone Before: A History of Apollo Lunar Exploration Missions Archived 12 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine", NASA Special Publication-4214, NASA History Series, 1989. URL accessed 15 August 2006.

- ^ Instruction manual for Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles IV: Turtles in Time at Gamers Graveyard.

- ^ Canaveral, Associated Press in Cape (4 May 2015). "To boldly brew: Italian astronaut makes first espresso in space". the Guardian.

- ^ "Space Quest: The Sarien Encounter [PC]". gamepressure.com. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ^ Straczynski, J. Michael. "Voices of Authority". Babylon 5. Season 3, Episode 5. 29 January 1996

- ^ Adams, Douglas (1979). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-25864-8.

- ^ Krauss, Lawrence M. (1995). The Physics of Star Trek. HarperPerennial. ISBN 978-0-465-00559-8.